- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- with Inhouse Counsel

- with readers working within the Consumer Industries and Retail & Leisure industries

In a rare decision reached under the Industrial Design Act, RSC 1985, c I-9 (the Act), the Federal Court of Canada awarded the plaintiffs almost $650,000 in profits amounting to the full extent of the defendant's gross revenues for infringing the plaintiffs' registered industrial design.

SHOE COMPETITORS GO TOE-TO-TOE

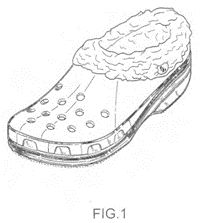

The plaintiffs in Crocs Canada, Inc v Double Diamond Distribution Ltd,1 Crocs Inc. and Crocs Canada, Inc. (collectively, Crocs), are the manufacturer and Canadian licensee, respectively, of the well-known "clogs" shoes made from injected ethylene-vinyl acetate foam. CROCS-branded shoes were unveiled in 2001 and have been sold in a variety of styles, including the CROCS MAMMOTH shoe, a variation on the "classic" and recognizable CROCS shoe design that incorporates "a prominent liner which you could see through the holes in the shoe" and "adjusted to be taller and wider."2 An example CROCS MAMMOTH shoe is shown below:3

Crocs owned Canadian Industrial Design Registration No. 120,939 for SHOE (the 939 Registration). That registration applied to "the visual features of [the CROCS MAMMOTH shoe depicted] in the drawings, whether those features are features of shape, pattern, configuration or ornament or are a combination of any of these features." Examples of drawings from the 939 Registration, which expired on December 30, 2018 following a 10 year term, are shown below:

The defendant competitor, Double Diamond Distribution Ltd. (Double Diamond), imported and sold a line of clogs, also made from injected ethylene-vinyl acetate foam, that were manufactured in China and sold under the name FLEECE DAWGS.4 An example FLEECE DAWGS shoe is shown below:5

Crocs commenced a claim against Double Diamond, alleging that the FLEECE DAWGS shoes were unlawful imitations of their CROCS MAMMOTH shoes and an infringement of the 939 Registration. In its defence, Double Diamond argued that its FLEECE DAWGS shoes were substantially different from (and therefore not infringements of) the 939 Registration, and in the alternative, that the 939 Registration was invalid. Double Diamond alleged that Croc's design was not novel as required by Section 8.2(1) of the Act and that the 939 Registration covered more than one design contrary to Section 10 of the Industrial Design Regulations, SOR/99-460 (the Regulations). Double Diamond counterclaimed for expungement of the 939 Registration.

THE PARTIES' BEST FEET FORWARD...

Crocs' evidence consisted of two keys witnesses. Crocs' Senior Vice President, Sourcing and Product Development, testified to the history of Crocs and the rationale behind the design choices made in the creation of the shoe, including the fleece liner and arrangement of the holes in the shoe.6 Crocs also led expert evidence in footwear design, who testified to the novelty of the design embodied by the 939 Registration and that no feature of the design "was dictated solely by function." Even the fleece liner, which Double Diamond argued served only to provide warmth, served an ornamental purpose because it was folded over the collar of the shoe.7

Double Diamond presented two fact witnesses. Mr. Mann, the founder, President, and CEO of Double Diamond, testified to the history of Double Diamond and the manufacturing of the defendant's shoe in China.

Mr. Mann's evidence was that he "designed around Crocs"8 but Double Diamond's other fact witness, Mr. Chen, testified that his factory in China created the design. Mr. Chen, the general manager of the factory in China retained by Double Diamond, explained the design process for Double Diamond's shoes and stated that "there was no such product on the market at the time."9 While Double Diamond served and filed its own expert report, the report was withdrawn during the trial.

A CROC BY ANY OTHER NAME...

The Court ruled in favour of Crocs and dismissed Double Diamond's counterclaim for expungement of the 939 Registration.

Crocs' Design is Original and Not Invalidated by Prior Art

First, Justice Fuhrer considered the validity of Crocs' design. She concluded that the 939 Registration covered permitted "variants" of the same design as opposed to more than one design.10 The "second design" alleged by Double Diamond simply showed some of the collar of the shoe being displaced, and this difference was not substantial enough to constitute a different design from the rest of the figures of the 939 Registration.

Next, Justice Fuhrer concluded that the 939 Registration was novel. Noting that "originality must be assessed from the perspective of the informed consumer who is familiar with the relevant market,"11 the Court accepted Crocs' expert evidence that no other designs embodying the unique features of the CROCS MAMMOTH shoe existed in the prior art.12 The other shoes in evidence differed substantially from Crocs' design and the Court was not prepared to assign any weight to additional shoes introduced by the defendant at trial, which the defendant had neither pleaded nor afforded Crocs' expert the ability to examine and opine on them.13

Justice Fuhrer concluded her analysis on the validity of the 939 Registration by finding that, despite the fact that some of the features of the design had some utilitarian function, they also had ornamental appeal and were therefore not "dictated" by their function.14 For example, the fleece liner did provide warmth to the wearer, but there was more than one way that this feature could look,15 and the "rivets" on the shoe were both ornamental and functional.16

Double Diamond Infringed Crocs' Design

Having concluded that the 939 Registration was valid, the Court conducted the four-part infringement test from the perspective of the informed consumer:17

- examine the prior art and the extent to which the registered design differs from any previously published design;

- assess the design for any utilitarian function, or any method or principle of manufacture or construction;

- examine the design itself to determine the scope of protection based on the figures and accompanying description in the registration;

- conduct a comparative analysis of the registered design and allegedly infringing article, taking the first three factors into account.

The Court noted that, as the prior art was not crowded, the 939 Registration should be afforded a broader scope of protection.18 However, since the drawings and description in the 939 Registration covered the entire design conducting the comparative analysis. the defendant's article needs to be "quasi-identical" in order to be considered infringing.19 The Court accepted Crocs' expert evidence, which established that Double Diamond's FLEECE DAWGS shoe was "nigh identical" to Crocs' CROCS MAMMOTH shoe and any differences between them were insubstantial.20

Remedy: A Croc of Gold

Turning to the appropriate remedies, the Court held that Crocs was entitled to an accounting of Double Diamond's profits commencing three-years prior to the commencement of this action (in keeping with the limitations provisions in the Act) and ending on the expiry date of the 939 Registration.21

In calculating the amount, Justice Fuhrer noted that Double Diamond's admitted gross revenues for this period were $649,779.17. The Court awarded the full amount of these revenues to Crocs because Double Diamond failed to meet the burden of proving deductible expenses to differentiate between Double Diamond's "revenues" and "profits." The only document that Double Diamond proffered to show deductible expenses was a "profit analysis" document based on unaudited financial statements. This document was prepared by an accountant formerly employed by Double Diamond who was not called as a witness at trial.22 The Court therefore dismissed the document and financial statements as being inadmissible hearsay and, even if they had been admitted, they would have had little probative value.23

In addition to awarding the full value of Double Diamond's revenues as "profits," the Court awarded Crocs pre- and post-judgment interest and costs in an amount to be agreed upon or determined by the Court in the future.

STRIDING INTO THE FUTURE

It is worth noting that this action began in 2017, and the Act and the Regulations were amended in 2018. Even though the Court's analysis concerned the "old" Act and Regulations and would likely be somewhat different under the current laws, this case remains interesting in several respects. In addition to being one of very few Canadian court decisions on industrial design infringement, this case is a good lesson for prospective rightsholders. Industrial design registrations are more than just powerful enforcement tools; they can also be demonstrably valuable intellectual property rights. This case also underscores the critical importance of strong expert evidence, including a robust report and a witness who thoroughly reviewed the applicable prior art.

For those parties where the "shoe is on the other foot" and they are defending against an industrial design infringement claim, it is critical to plead all prior art on which they intend to rely. Additionally, it is the defendant's responsibility to prove deductible expenses in order to differentiate between "gross revenues" and "profits." Without properly audited financial statements and reliable documentation, a defendant runs the risk of being liable for the full extent of their revenues if they cannot show proper deductible expenses.

Footnotes

1. 2022 FC 1443 (FC) [Crocs].

2. Crocs at para 26.

3. Crocs at para 22.

5. Crocs at para 24.

6. Crocs at para 19-26.

7. Crocs at para 39.

8. Crocs at para 58.

9. Crocs at para 68.

10. Crocs at para 77.

11. Crocs at para 82.

12. Crocs at para 84-85.

13. Crocs at para 91-93.

14. Crocs at para 95.

15. Crocs at para 97.

16. Crocs at para 100.

17. Crocs at para 103 [references omitted].

18. Crocs at para 105.

19. Crocs at para 113.

20. Crocs at para 115.

21. Crocs at para 117.

22. Crocs at para 60-62, 131-133.

23. Crocs at para 134.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.