- within Employment and HR topic(s)

- within Consumer Protection and Finance and Banking topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- with readers working within the Automotive, Banking & Credit and Basic Industries industries

"There has ... been a significant rebalance in favour of employees since the enactment of the" Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), the High Court of Australia said in a recent decision examining the obligation on employers to explore redeployment: Helensburgh Coal Pty Ltd v Bartley [2025] HCA 29 (6 August 2025).

Under the FW Act, a dismissal will not be unfair if the dismissal is a case of genuine redundancy. An element of what comprises a genuine redundancy is that there are no reasonable redeployment opportunities.

It is not uncommon for employers to explore redeployment opportunities by examining the vacancy list. It is also not uncommon for unions to argue that an employer should cease to engage contractors in preference for keeping employees employed in the business. Companies initiate restructures to address financial imperatives so they are often not too keen to cease the engagement of cheaper and skilled labour alternatives.

The High Court in Helensburgh was asked to resolve the tension as to whether the Fair Work Commission was permitted to inquire into whether an employer is required to make changes to how it uses its workforce to operate its enterprise. In this article, we examine the High Court decision and the implications for employers when implementing restructures.

The Fair Work Act 2009

Many employees are able to bring an unfair dismissal claim when dismissed, including for reasons of redundancy. However, a dismissal will not be unfair if the dismissal is a genuine redundancy: section 385.

Section 389 defines what is a genuine redundancy:

(1) A person's dismissal was a case of genuine redundancy if:

(a) the person's employer no longer required the person's job to be performed by anyone because of changes in the operational requirements of the employer's enterprise; and

(b) the employer has complied with any obligation in a modern award or enterprise agreement that applied to the employment to consult about the redundancy.

(2) A person's dismissal was not a case of genuine redundancy if it would have been reasonable in all the circumstances for the person to be redeployed within:

(a) the employer's enterprise; or

(b) the enterprise of an associated entity of the employer.

It is subsection (2) that was the centre of attention in the Helensburgh decision.

The facts

Helensburgh Coal Pty Ltd operated a mine. In doing so, it engaged employees and contracted labour from Menster Pty Ltd and Nexus Mining Pty Ltd; a blended workforce. Menster and Nexus provided labour to Helensburgh on an "as needs" basis.

Following a downturn in demand for coking coal due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Helensburgh restructured its operations, to reduce crew numbers and working days.

Following consultation and a request by unions to mitigate the impact of the restructure, Helensburgh agreed to some "insourcing" of work from Menster and Nexus thereby reducing the number of impacted employees to 90. Helensburgh otherwise continued to engage some labour from Menster and Nexus.

Twenty-two (22) employees who lost their job commenced unfair dismissal proceedings and were, through various decisions, successful in the Commission establishing that their dismissal was not a genuine redundancy within the meaning of s 389 of the FW Act.

Some critical findings made by the Commission included:

- There was no evidence that Helensburgh had any policy, or had made any formal or informal business decisions, or given any commitment, to use available workers from the contractor companies to perform jobs in preference to its own employees;

- Menster and Nexus supplied labour on an "as needs" basis (and one of the contracts was due to expire); and

- Helensburgh had, and continued to have, work that was ongoing and "sustaining" that it had not allocated to anyone. After the restructure, 60 contractors did this work.

What does s 389 of the FW Act mean?

As to the requirement in s 389(1) of the FW Act that the employer no longer requires the person's job to be done, the High Court emphasised the prerogative of the employer:

It is a factual inquiry about what happened. The first part of s 389(1)(a) turns on the existence of a decision in fact made by an employer. It is the employer's decision to no longer require a person's job to be performed by anyone. ... An employer determines what those changes might be ... There is no reasonableness inquiry in s 389(1)

However, s 389(2) is a "counter-factual":

It provides that notwithstanding that the employer no longer required the dismissed employee's job, namely their work or their duties, to be performed by anyone because of changes in the operational requirements of the employer's enterprise, the person's dismissal was nonetheless not a case of genuine redundancy "if it would have been reasonable in all the circumstances for the person to be redeployed within ... the employer's enterprise" (emphasis added)

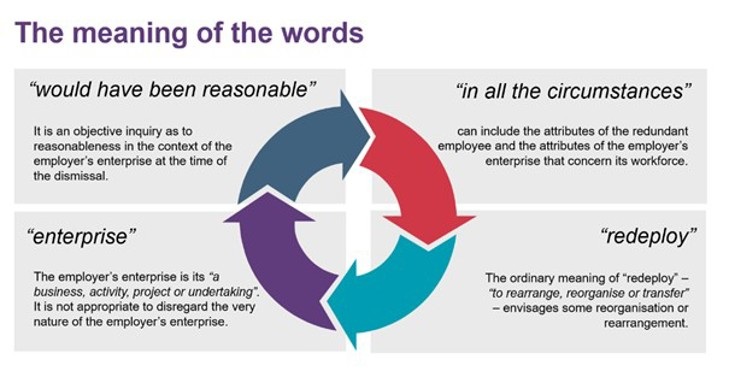

The High Court then examined the meaning of each element of the requirement: would [it] have been reasonable in all the circumstances for the person to be redeployed within the employer's enterprise or associated entity.

The High Court confirmed the breadth of the obligation to redeploy. "The text of s 389(2) ... does not, on its face, assume that a job is readily available. Rather, "redeployed" looks to whether there was work, or a demand for work, within the employer's enterprise or an associated entity's enterprise that could have been performed by the otherwise redundant employee".

Further, "[t]he language of s 389 does not prohibit asking whether an employer could have made changes to how it uses its workforce to operate its enterprise so as to create or make available a position for a person who would otherwise have been redundant", the High Court majority said. There are no proscriptive rules.

Redeployment: beyond vacancies

The High Court majority identified that redeployment involves, amongst other things, looking:

- beyond vacancies;

- at an employee's skills and experience and whether training can be provided to the employee to do an available job;

- at anticipated changes, like parental leave, retirements, contract expiring or temporary positions to redeploy an employee; and

- at contracts ("as needs" or long-term and fixed) of contractors and labour hire workers.

Based on the facts in this case, it was determined that it would have been reasonable in all the circumstances for the employees to be redeployed within Helensburgh's enterprise as there was work available.

What about the employer's prerogative?

Edelman and Stewart JJ, while agreeing with the majority decision, were perhaps more balanced on the inquiry into compliance with redeployment obligations.

Both recognised that "[t]he employer's enterprise includes the employer's "policies and practices in relation to the use of labour, including as to whether to use permanent employees, independent contractors, casual labour, or contractors"". In an unfair dismissal claim, they said, "The Commission has no authority to consider the reasonableness of a redeployment that would involve any significant change to any of these matters such that there would be a change in the enterprise, properly characterised, at the date of dismissal".

For Stewart J, the fact that "insourcing" would involve displacing other employees is a matter of "great weight":

...it must be accepted that it would be difficult to conclude that redeployment is reasonable if that meant that another person with a job, for which there is a business need, has to make way for someone else whose job was no longer needed. It would make very little sense in the ordinary case to conclude that it was reasonable to redeploy a person by terminating the permanent employment of another person. No different conclusion might be expected if the other person were employed by a contractor, or if they were themselves independent contractors or casual labourers. Redeployment of a person at the expense of another person's position would be a very grave step to take and would be unlikely to be a reasonable outcome

Stewart J may have found the dismissal a genuine redundancy if Helensburgh had a clear policy preferring contracted labour and did not have available work.

Takeaways

The High Court decision may not, in a significant way, impact smaller businesses, businesses that do not have blended workforces and small discrete restructures.

Businesses that use blended workforces, or businesses that use service providers for non-core activities, need to carefully document its business model. This will help inform, and influence, the examination of what reasonable redeployment is. An employer would not be expected to employ employees in non-core activities that it exclusively outsources.

"All the circumstances" requires employers to look at the full picture, this includes beyond vacancy lists and examining whether there is meaningful available work in the enterprise or an associated entity – at the time of the dismissal or in the immediate future. Businesses need to consider what opportunities exist as part of their broader workforce strategy.

But, as Justice Raper of the Full Federal Court said, it would be "rare" for the Commission to consider it reasonable, in all the circumstances, for an employer to insource positions that are already filled by contractors. It was a combination or critical facts (see above) that meant Helensburgh had not explored reasonable redeployment in all of its circumstances.

For more information on a specific restructure, please reach out to us.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.