The term "running account" will be familiar to most businesses which engage in the supply of goods and services. It is used to describe a situation where goods are supplied on credit and there are a series of transactions (supply of new goods or services and payments on account) between supplier and purchaser which result in the level of indebtedness to the supplier fluctuating.

A running account is of particular importance to the law of insolvency which applies to unfair preferences.

The Corporations Act has a series of provisions which allow a liquidator to treat payments made by the company to unsecured creditors in the period leading up to its being wound up as voidable. The overriding principle behind the legislative provisions is "pari passu" – unsecured creditors of a company in liquidation are to share in the assets of the company on an equal basis, proportionate to the amount of the debt owed to them.

The unfair preference provisions seek to give a liquidator the ability to give effect to this principle by recovering payments made to unsecured creditors which the law considers give an unfair preference – more to the creditor than if the creditor were to refund the payment and prove for the debt in the winding up of a company.

Initially the Common Law, and subsequently legislation, sought to limit what could be considered a harsh effect of the unfair preference provisions through the doctrine of a running account.

The High Court, in Richardson v The Commercial Banking Company of Sydney Ltd (1952) 85 CLR 110 established the running account defence. It was held that "in a case where the payment/s form an integral or inseparable part of an entire transaction its effect as a preference involves a consideration of the whole transaction". Where a running account exists between a creditor and the company in liquidation, not every payment made is considered as a preference in isolation. A single preference will exist if the overall effect of the relationship was to reduce the indebtedness of the company to the creditor in the statutory period. The statutory period, originally contained in the provisions of the Bankruptcy Act, which was adopted in the various Corporations' statutes, is 6 months prior to the relation back day (a day defined in the legislation).

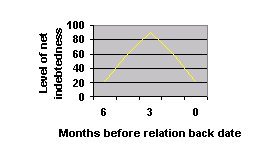

The general pattern which occurs in the lead up to a company's liquidation is that its level of indebtedness with individual creditors initially increases within the 6 month period (as the company struggles to pay its debts in an attempt to survive) and then the level reduces as the creditors attempt to get paid in an attempt to bring the account back to within acceptable levels. Graphically, the relationship can be portrayed as follows:

In Rees v Bank of New South Wales (1964) 111 CLR 210, it was submitted by the creditor that the test for a single preference should be a comparison of the debt at the start of the statutory period of six months to the date of liquidation. From the graph above it can be seen that it would often result in no preference at all. It was held by Barwick CJ (at p. 136) that "the liquidator can choose any point during the statutory period in his endeavour to show that from that point on there was a preferential payment and I can see no reason why he should not choose, as he did here, the point of peak indebtedness of the account during the six months period".

In Queensland Bacon v Rees (1966) 115 CLR 266, Barwick CJ expanded on his previous statements in relation to a running account (at 286) : "implicit in the circumstances in which the payment is made is a mutual assumption by the parties that there will be a continuance of the relationship of buyer and seller...it is impossible to pause at any payment into the account and treat it as having produced an immediate effect to be considered independently of what followed."

On the strength of the above authorities, liquidators used the "high point, low point" analysis to calculate a single preference in the event of a creditor relying on a running account defence. Whether that is the correct analysis as a matter of law is not as settled as one might expect.

The High Court next considered the law applicable to running accounts in Airservices Australia v Ferrier (1996) 185 CLR 483. The case involved the collapse of Compass Airlines in 1992. In the statutory period, Airservices provided services to the value of $17.8 mn and received 9 payments from Compass totalling $10.3 mn.

The majority, Dawson Gaudron and McHugh JJ said of a running account "if the purpose of the payment is to induce the creditor to provide further goods or services as well as discharge an existing indebtedness, the payment will not be a preference unless the payment exceeds the value of the goods or services acquired. In such a case a court...looks to the ultimate effect of the transaction". This doctrine of ultimate effect was expanded upon in an economic way (at 495): "If at the end of a series of dealings, the creditor has supplied goods to a greater value than the payments made to it during that period, the general body of creditors are not disadvantaged by that transaction – they may even be better off. The supplying creditor, therefore, has received no preference.

On the basis that Airservices had supplied services whose value far exceeded, the value of the payments made by Compass, the majority held that none of the payments (excepting the last of $1.7mn) had the effect of preferring Airservices over other creditors. The liquidator failed to recover those last payments.

Because of the fact that the indebtedness of Compass increased throughout the 6 month period, it was not necessary for the Court to look at the high point low point analysis which was previously established.

What is of significance in the decision of the majority is the obiter contained throughout the majority judgement which indicates the ultimate effect of the running account is to be compared from the commencement of the 6 month period. For example, consider the following quotes from the majority judgement:

- "At the end of the six month period, Airservices was more than $8mn worse off than it had been at the commencement of the period" (at 496)

- "...the court does not regard the individual payments as preferences even though they were unrelated to any specific delivery of goods or services and may ultimately have had the effect of reducing the amount of indebtedness of the debtor at the beginning of the six month period. If the effect of the payments is to reduce the initial indebtedness, only the amount of the reduction will be regarded as a preferential payment."

It follows that if this is the correct interpretation of the majority reasoning, liquidators will be at risk in using a high point – low point analysis. It is unknown whether the majority considered the importance of these words in handing down its judgement. Because the issue never arose for consideration before the Court, it is submitted that the Court has not decided to overrule the decision of Barwick CJ in Rees –v- Bank of New South Wales with respect to the liquidator choosing any point (the peak indebtedness) with which to commence the single preference.

The legislation

The statutory 6 month period originally contained in the Bankruptcy Act has been decided upon by the legislature on an arbitrary basis. It can be argued that Barwick's reasoning is equally arbitrary.

All the High Court cases referred to above were decided in the light of s.122 of the Bankruptcy Act, which was adopted by incorporation to the various Corporations' Legislation.

In 1993, significant amendments were made to the Corporations Law in the area of insolvency. This was done after a 1988 ALRC report into insolvency (commonly referred to as the Harmer Report). The Harmer Report contained recommendations with respect to the avoidance provisions as follows:

129. Time Period

- The existing 6 month time period for review of preferential transactions involving non related creditors should be retained.

131. Running Accounts

- There should be a statutory provision which allows the court to have regard to the relationship between the parties and, if appropriate, the history of transactions between them to determine if there has been a preferential transaction or transactions.

The new statutory provision which has been in effect since 1993 provides:

588FA Unfair preferences

"(1) A transaction is an unfair preference given by a company to a creditor of the company if, and only if:

(a) the company and the creditor are parties to the transaction (even if someone else is also a party); and

(b) the transaction results in the creditor receiving from the company, in respect of an unsecured debt that the company owes to the creditor, more than the creditor would receive from the company in respect of the debt if the transaction were set aside and the creditor were to prove for the debt in a winding up of the company;

even if the transaction is entered into, is given effect to, or is required to be given effect to, because of an order of an Australian court or a direction by an agency.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), a secured debt is taken to be unsecured to the extent of so much of it (if any) as is not reflected in the value of the security.

(3) Where:

(a) a transaction is, for commercial purposes, an integral part of a continuing business relationship (for example, a running account) between a company and a creditor of the company (including such a relationship to which other persons are parties); and

(b) in the course of the relationship, the level of the company's net indebtedness to the creditor is increased and reduced from time to time as the result of a series of transactions forming part of the relationship;

then:

(c) subsection (1) applies in relation to all the transactions forming part of the relationship as if they together constituted a single transaction; and

(d) the transaction referred to in paragraph (a) may only be taken to be an unfair preference given by the company to the creditor if, because of subsection (1) as applying because of paragraph (c) of this subsection, the single transaction referred to in the last-mentioned paragraph is taken to be such an unfair preference."

The above section codifies the common law position. In the event there is a running account, all the transactions forming part of the relationship are considered together as a single transaction. Only if the single transaction gives rise to a preference will a liquidator succeed.

What it does not make clear is whether "all transactions" means all transactions throughout the six month statutory period (as appears to be contemplated by the majority in Airservices) or all transactions from the point of peak indebtedness during the period as chosen by the liquidator (per Barwick in Rees v Bank of New South Wales).

Authority subsequent to the 1993 Amendments and Airservices

While Airservices was decided in 1996, because Compass was placed into liquidation in 1991, the new legislative provisions were not applicable.

The High Court has not had to consider an unfair preference case since the new provisions came into being. Nor has it had to consider the issue of whether Airservices overrules Rees v bank of New South Wales.

In Sutherland v Liquor Administration Board (1997) 15 ACLC 875, Young J, sitting as a single judge in the NSW Supreme Court, attempted to interpret the new provision as follows:

"Although this is a very verbose section and the concatenation of words is sometimes difficult to comprehend, in a simple case it means that if a supplier and consumer are constantly trading...then one does not look at transactions in isolation but looks at the overall effect at the beginning and the end of the period. That is an inadequate summary but is perhaps generally more meaningful than the words of the subsection itself."

Young J is clearly interpreting the section as comparing balances at beginning and end of the 6 month period. Probably because he was interpreting legislation which formed no part of the decision of Airservices, he does not refer to that decision to support his beginning and end interpretation.

More recently, in Sutherland (in his capacity as liquidator of Sydney Appliances Pty Ltd (in Liq) –v- Eurolinx [2001] NSWSC 230, Santow J considered the very same issue and adopted the interpretation of Young J above except as follows:

"I would measure the preference, if any, by reference to the period of the relevant transactions constituting the running account, within the 6 month relation back period. I would do so by reference to the highest amount owing during the relation back period, not necessarily "at the beginning", compared to the amount owing on the last day, following Rees; see also Barlow 'Voidable Preference – the High Court Re-Considers' (1998) ABLR 82 at 92."

Barlow in the above mentioned article analyses the Airservices' decision in depth in relation to the running account issue. At the conclusion of all this analysis, which includes a reference to Young J's decision in Sutherland, he relies on Rees v Bank of NSW to state:

"It is not correct to compare the situation at the beginning of the relation back period with that at the end...Rather one must look at the period from the date during the relation back period when the highest amount was owed to the last day".

It is clear that is what Rees stands for. It is equally clear that the majority in Airservices was referring to a beginning and end test to ascertain the ultimate effect. What is not clear is whether the majority did this intentionally with a view to create an inconsistency with Rees.

Conclusion

There is an undeniable tension between the reasoning in Airservices and the established high point low point analysis. The doctrine of ultimate effect, as expounded in Airservices, does not accord with the commencement of the period being the highest point of indebtedness.

Notwithstanding this, it is submitted that the correct state of the law is that Rees must prevail as it is part of the ratio of that case, wheras the matter was not specifically considered and overruled by the majority in Airservices.

While liquidators can continue to enjoy the arbitrary selection of the commencement of the single transaction, it remains to be seen how long their ability to do so will exist. With the differing decisions in lower jurisdictions (Supreme Courts) the issue may not be put finally to rest until an appropriate case comes before the High Court.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.