- within Tax topic(s)

- in United States

- in United States

- within Antitrust/Competition Law, Food, Drugs, Healthcare, Life Sciences and Wealth Management topic(s)

Traditionally, the Dutch government presents its budget plan to parliament on the third Tuesday in September. It contains tax proposals for the coming year (the 2025 tax plans). In this article, we address elements of the 2025 tax plans relevant to U.S. multinational enterprises or U.S. investment funds with Dutch entities in their structure.

The article begins by addressing relevant changes to the Dutch tax code, specifically concerning the earnings stripping rule. We then set out amendments to the Dutch tax code that facilitate the interaction between certain Dutch subject-to-tax tests (STTs) and the OECD's global anti-base-erosion (GLOBE) model rules.1 Subsequently we address the main changes in connection with Dutch withholding taxes and legislation on the tax classification of entities that is already enacted and comes into effect in 2025. We conclude by briefly highlighting some other elements of the 2025 tax plans.

Earnings Stripping Rule

Increase of Fiscal EBITDA Cap to 25 Percent

The first EU antitax avoidance directive2 required all EU member states to, inter alia, implement a so-called earnings stripping rule in their domestic tax laws. Under the Dutch implementation, the deductibility of net interest expenses is limited to the higher of (i) 20 percent of the fiscal earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization or (ii) a threshold of €1 million. The earnings stripping rule applies to both group and third-party loans.

The 2025 tax plans propose to increase the fiscal EBITDA cap from 20 percent to 25 percent. This is positive news for Dutch subsidiaries of U.S. MNEs with debt obligations because it potentially increases the amount of interest that can be deducted for Dutch corporate income tax purposes.3

Earning Stripping Rule and Real Estate Companies

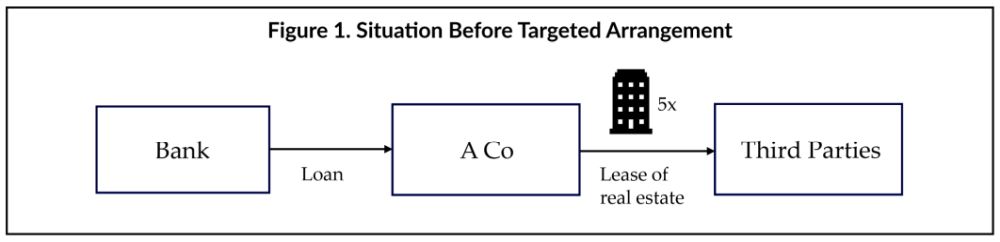

On the other hand, the deductibility of interest under the earnings stripping rule is proposed to be tightened for some real estate investment companies. Under the 2025 tax plans, a real estate company is considered an entity whose adjusted assets — for at least half of the year — consist of 70 percent or more of immovable property to the extent the immovable property is leased to third parties. This measure prevents Dutch taxpayers from splitting up companies for the purpose of using the €1 million threshold mentioned above at the level of each separate entity. This is clarified in the example below. (See Figure 1.)

In the above example, A Co takes out a loan from a third-party bank to (fully) finance the acquisition of five real estate properties. A Co subsequently puts these real estate properties at the disposal of third-party tenants. Under the current earnings stripping rules, interest deduction on the loan is limited to the higher of €1 million or 20 percent of the (adjusted) fiscal EBITDA.

Let's assume that the value of the five real estate properties amounts to €100 million, while rental revenues are €5 million per year. The real estate is debt-financed at a 4 percent rate. As such, the profit realized by A Co therefore amounts to €1 million. The fiscal EBITDA, for purposes of the earnings stripping rule, amounts to €5 million (€5 million rental revenue and disregarding the interest expenses). This means that 20 percent of the fiscal EBITDA is equal to the threshold of €1 million and therefore, by applying the earnings stripping rule, the interest deduction is restricted to €3 million. The taxable profit is therefore €4 million.

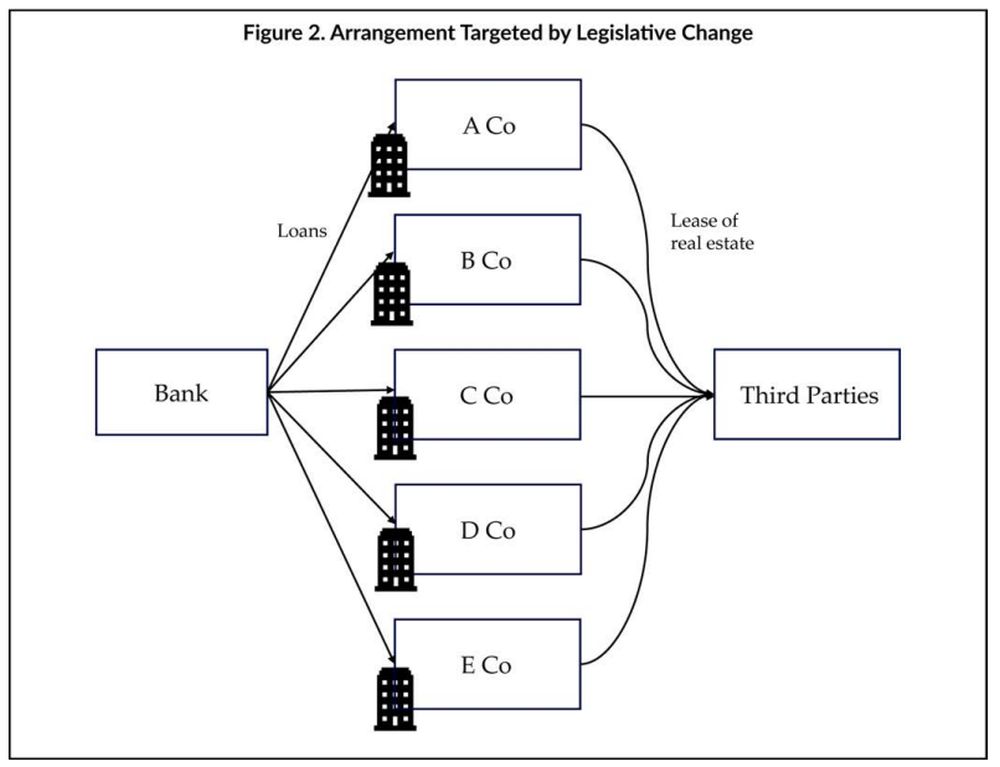

In the above example, it could be beneficial for A Co from an earnings stripping rule perspective to split the real estate properties over five separate legal entities to be able to use the €1 million threshold five times (at the level of five separate legal entities), instead of once. (See Figure 2.)

The facts and circumstances remain otherwise unchanged. The real estate value is €20 million per entity. The rental income is €1 million per year per entity. The real estate is fully debt-financed, and the interest rate on the loan remains at 4 percent.

The profit per taxpayer is €200,000 — rental income of €1 million minus the interest expenses of €800,000. In this case, by applying the earnings stripping rule, there is no interest deduction restriction because the interest expense per taxpayer does not exceed the €1 million threshold. The taxable profit is therefore €200,000 per taxpayer and €1 million total.

Under the 2025 tax plans, to prevent the above arrangements, real estate companies will no longer be able to apply the €1 million threshold — only the (proposed) 25 percent fiscal EBITDA threshold. Whether this is in fact detrimental for U.S. permanent establishment funds with real estate in the Netherlands depends on how these PE funds have structured their investments.

GLOBE Model Rules, STTs, and Dutch Tax Law

The Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act 1969 (CITA) includes STTs in relation to several provisions. These STTs generally serve as an escape for the application of an antiabuse measure if the relevant entity, asset, or transaction is subject to a reasonable level of income tax (generally 10 percent), determined in accordance with Dutch tax standards.

The 2025 tax plans provide helpful clarification on the interaction between the GLOBE model rules and these STTs by clarifying that a "tax on profits" in this sense also includes certain taxes levied based on the GLOBE model rules. The proposed amendments are inter alia relevant for the application of the STTs in the following CITA provisions.

The Anti-Base-Erosion Provision of CITA Article 10a

Dutch tax law contains an anti-base-erosion rule in CITA article 10a that can deny the deductibility of intragroup interest expenses. Under this rule, the deduction of interest expenses incurred on a debt toward a related entity that has been used to finance a so-called tainted transaction (a dividend distribution or capital contribution) is as a general rule denied. An exception applies, inter alia, if the corresponding interest income is subject to a reasonable level of tax on profit at the level of the intragroup creditor.4

The 2025 tax plans clarify that a tax on profit in this sense also includes GLOBE top-up taxes levied under a qualified domestic minimum topup tax (QDMTT), income inclusion rule, or undertaxed profits rule. In regard to CITA article 10a, the commentary to the 2025 tax plans says that top-up taxes levied under the IIR and UTPR can be taken into account because the Netherlands already considers taxes on controlled foreign corporations as tax on profits for purposes of CITA article 10a.5

Exemptions for Foreign PE Income

The participation and object exemptions provide exemptions from Dutch corporate income tax on income derived from qualifying participations and PEs. Both regimes have a broad scope but do not apply if the participation or PE is held as a portfolio investment and is not subject to a reasonable level of tax on its profits.

The 2025 tax plans clarify that "tax on profit" in this sense also includes top-up taxes levied under a QDMTT (the UTPR and IIR are not mentioned). This means that a participation held as a portfolio investment and not subject to corporate income tax in its country of residence can now qualify for the participation exemption if its profits are subject to top-up taxes in the residence country under a QDMTT.

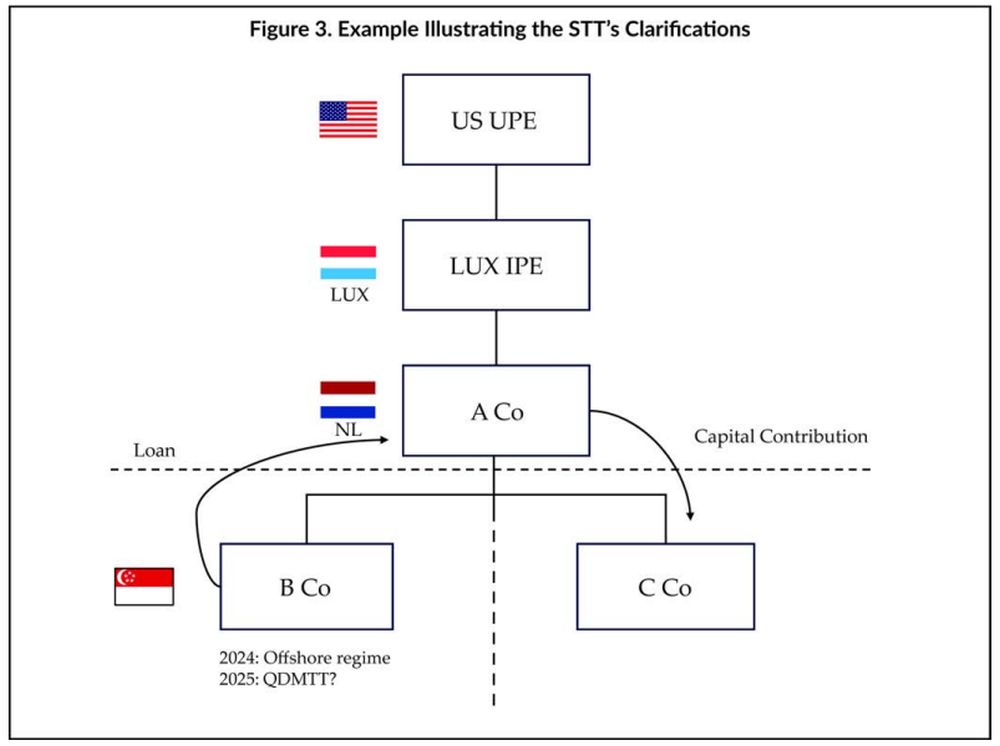

We discuss the interaction between the GLOBE model rules and these STTs through the following example. (See Figure 3.)

In the above example, the Dutch entity A Co takes up a loan from its wholly owned subsidiary B Co, an entity based in Singapore. We assumed that interest income derived by B Co is not subject to tax in Singapore.6

The interest deduction on the loan is, as a general rule, limited under CITA article 10a because it concerns a loan from a related entity (B Co) that has been used for a tainted transaction (the capital contribution into C Co). Under the current rules, the STT cannot be relied upon as an escape because the interest income is not subject to Singapore corporate income tax at the level of B Co.

This would be different as of January 1, 2025, if Singapore were to levy a top-up tax on the profits of B Co following the enactment of a QDMTT. In that case, the STT can be invoked, and the deduction of the interest expense would no longer be limited under CITA article 10a.7

Also, under the current rules, income derived from B Co is not expected to benefit from the Dutch participation exemption regime. The reason is that the participation in B Co is (deemed to be) held as portfolio investment and B Co is not subject to corporate income tax in Singapore. However, B Co should meet the STT in the participation exemption next year if Singapore enacts the QDMTT, meaning income derived from A Co's shareholding in B Co could become eligible for the Dutch participation exemption.

Top-Up Tax Scope and the Participation Exemption

It is worthwhile to note that for the STT in the anti-base-erosion provision of CITA article 10a on top-up taxes levied under a QDMTT, IIR and UTPR can be taken into account. On the other hand, this is limited to top-up taxes levied under a QDMTT for the STT in the participation exemption regime. We expect that the reasoning for this distinction lies in the ordering rules that were also discussed in the administrative guidance issued by the OECD on February 2, 2023, to the GLOBE model rules.8

Let's assume that Singapore does not implement the QDMTT next year. For purposes of the GLOBE model rules, a taxable dividend in the hands of a foreign shareholder would be considered a covered tax at the level of the lowtaxed constituent entity (LTCE).9 In the example above, this would mean that the Dutch corporate income tax due on the dividend received by A Co, if the participation exemption does not apply in the absence of a QDMTT, would be considered a covered tax at the level of B Co.

It is further assumed that B Co realizes income in the amount of 100. B Co distributes only 40 percent of its income to A Co. This distribution is subject to Dutch corporate income tax at 25.8 percent, resulting in 10.32 percent Dutch corporate income tax due. In that case, after allocating the Dutch corporate income tax due in the Netherlands on the dividend received, B Co remains insufficiently taxed under the GLOBE rules. This is because the effective tax rate at the level of B Co is below 15 percent (10.32 percent). As a result, the Luxembourg intermediate parent entity in the example above will be required to levy an IIR in the amount of 4.68 percent to ensure that B Co's effective tax rate is 15 percent.10

If the Dutch participation exemption regime includes the IIR levied at the level of LUX IPE, it would result in the Netherlands no longer levying corporate income tax on the dividend. This is because the Luxembourg IIR would increase the Dutch corporate income tax such that it would no longer be a covered tax B Co. This would be a somewhat illogical outcome, given that under the GLOBE rules, covered taxes must first be allocated to the LTCE and only then is an IIR levied to ensure that the ETR at the LTCE level is 15 percent. Moreover, it could create a circularity issue in which application of the IIR on the one hand and the Dutch participation exemption regime on the other become dependent on each other. The Dutch Association of Tax Advisers has asked a question on the reasoning behind considering a QDMTT as only a top-up tax for purposes of the STT in the participation exemption regime. This question is expected to be addressed during the parliamentary proceedings of the 2025 tax plans.

Withholding Taxes

Conditional Withholding Tax Uncertainty

Generally, the Netherlands does not levy withholding tax on interest and royalty payments. Also, it has a broad domestic dividend withholding tax exemption available for beneficiaries in EU countries, as well as countries with which the Netherlands has concluded a double tax agreement containing a dividend article. Usually, dividend distributions from a Dutch subsidiary to a U.S. corporate shareholder benefit from this domestic dividend withholding tax exemption.

In some situations, however, the Netherlands levies a so-called conditional withholding tax (CWT) on outbound payments to "affiliated" entities holding a qualifying interest (generally an interest above 50 percent) in specific EUblacklisted or low-taxed jurisdictions (LTJ).11 The CWT rules also apply if outbound payments are made to hybrid entities or in cases of tax abuse. This could be an issue in fund dividend distributions by Dutch entities with limited partnerships (fund LPs) as shareholders.

The problem is that a fund LP holding an interest in a Dutch entity is generally considered a hybrid entity for Dutch tax purposes (opaque in the Netherlands and transparent in its country of residence) under Dutch entity classification rules. This means that, for example, dividend payments by a Dutch entity to a fund LP are, as a general rule, subject to CWT at a rate of 25.8 percent. This changes only if a look-through rule applies that stipulates that there are no investors in the fund LP that (i) hold a qualifying interest (more than 50 percent) and (ii) are resident in an LTJ. It is very unlikely there will be an investor with an interest of more than 50 percent in the fund LP that is also resident in an LTJ.

However, the definition of qualifying interest has been extended to include the cooperating group. The cooperating group has deliberately not been defined in Dutch tax laws and is interpreted strictly by Dutch tax authorities. Initially, there was a risk that fund LP investors could be viewed as a cooperating group and that an investor located in an LTJ (a "tainted investor") could taint the entire cooperating group. In that case, outbound payments to the fund LP would be subject to CWT.As an example, if a Cayman Islands investor in the fund LP holds a 5 percent interest, the Dutch entity's dividend distribution to the fund LP would be subject to CWT for 100 percent because the investors are viewed as a cooperating group — the Cayman Islands investor would taint the entire cooperating group for CWT purposes.

The New Dutch Entity Classification Rules

As set out in more detail below, the Netherlands will introduce new entity classification rules on January 1, 2025. Under these rules, Dutch LPs and their foreign equivalents will be classified by default as transparent for Dutch tax purposes. This means that a fund LP holding interest in a Dutch entity will be classified as transparent for Dutch tax purposes and remove the hybrid entity within the meaning of the CWT rules. The Dutch government has indicated that the new entity classification rules may be applied in 2024 for dividend CWT purposes, provided the fund LP itself is not incorporated under the laws of an LTJ.12

This reduces potential CWT in a collaborating group of fund LP investors to the pro rata portion of the dividend allocable to the tainted investor for 2024. In our previous Cayman Islands example above, the dividend distribution to the fund LP would still be subject to CWT. However, the tax would be due only on the 5 percent allocable to the Cayman Islands investor, instead of the 100 percent in the example above. Although this provides welcome relief, there remains the difficult issue for PE funds of determining the percentage held by tainted investors, particularly in fund-of-fund situations.

To view the full article, click here.

Foonotes

1. OECD, "Tax Challenges Arising From the Digitalisation of the Economy — Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two)" (2021).

2. Council Directive (EU) 2016/1164 of July 12, 2016, laying down rules against tax avoidance practices that directly affect the functioning of the internal market.

3. Other interest deduction limitations under Dutch domestic law should be taken into account in this respect, such as the anti-base-erosion rule contained in article 10a of the Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act and the ATAD 2 antihybrid rules. The latter could, for instance, be relevant for U.S. parent entities that grant a loan to a Dutch subsidiary that is treated as a disregarded entity for U.S. tax purposes.

4. In case the STT is not met, a Dutch taxpayer may still be able to deduct interest on the loan, if it demonstrates that the loan and the tainted transaction have been entered into for valid business reasons.

5. The subpart F regime can be considered a CFC regime for this purpose.

6. We understand that the interest income would not be subject to corporate income tax in Singapore under an offshore regime, provided the relevant interest payments are not remitted to Singapore.

7. The Dutch tax inspector could still argue that both the loan and the capital contribution to C Co have not been entered into for business reasons. However, the burden of proof lies with the tax inspector if the interest is STT at the level of B Co.

8. OECD, "Tax Challenges Arising From the Digitalisation of the Economy — Administrative Guidance on the Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two), February 2023" (2023).

9. See article 4.3.2.(e) GLOBE model rules.

10. See article 2.1.2. GLOBE model rules. In the example, LUX IPE as the intermediate parent entity would be required to apply the IIR, absent the U.S. having implemented the GLOBE model rules.

11. As an example, for purposes of these CWT rules, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands are considered low-taxed jurisdictions, while Russia and Panama are considered EU-blacklisted jurisdictions.

12. This transitional rule can therefore be relied upon if the fund LP is a Delaware LP or a Luxembourg special limited partnership but not if it concerns a Cayman Islands LP.

Originally published by taxnotes

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.