- within Environment topic(s)

- in European Union

- in European Union

- with readers working within the Oil & Gas and Utilities industries

- within Environment, Finance and Banking and Technology topic(s)

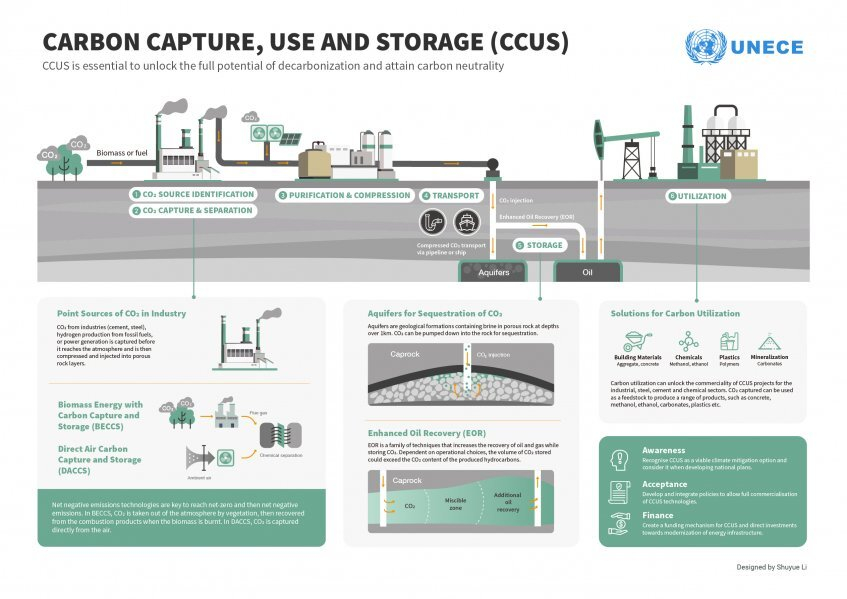

Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) is increasingly

recognised worldwide as a critical mechanism for reducing CO₂

emissions from industrial and energy facilities. As of today, 77

commercial carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects are

operational worldwide, with a combined capture capacity of 64

million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of CO₂ 1.

The core concept of CCS involves capturing carbon dioxide at

emission sources, transporting it, and injecting it into deep

underground formations where it can be stored permanently. This

technology is essential for mitigating climate change, particularly

in sectors where emissions cannot be eliminated solely through

renewable energy.

Kazakhstan is one of the world's carbon-intensive economies,

heavily reliant on fossil fuels and energy-intensive industries.

Although Kazakhstan currently lacks a dedicated legal or regulatory

framework governing CCUS, the country has adopted ambitious climate

commitments, including carbon neutrality by 2060, and is expected

to introduce supportive regulations in the coming years.

Understanding the compatibility of CCUS projects with existing laws

is therefore essential for project developers and investors.

Global practice recognises several types of deep geological

formations suitable for long-term CO₂ storage, from

which two formations are particularly relevant for Kazakhstan:

- Depleted oil and gas reservoirs represent a favourable and well-studied option. Their geological characteristics, including porosity, permeability and structural integrity, have been extensively assessed during years of hydrocarbon extraction. Existing wells, pipelines and injection facilities can often be repurposed. In addition, CO₂ injection may support enhanced oil recovery (EOR), improving the economic viability of early CCUS projects.

- Saline aquifers represent a second option for implementing CCUS projects as they constitute formations containing highly mineralised water at depths exceeding 800-1000 meters. Such water is not suitable for drinking or industrial use and is found extensively across Kazakhstan. International bodies such as the IPCC recognise deep saline formations as one of the most promising long-term CO₂ storage options due to their large capacity and widespread distribution. Salt domes are another potential option for CO₂ storage, but Kazakh legislation does not yet contain a defined licensing regime for their use.

Image credit: UNECE 2.

Development of CCS Regulation Across

Jurisdictions

The regulatory foundations for carbon capture and storage (CCS)

were laid the earliest in Norway, which in 1996 launched the

Sleipner project and relied on the Petroleum Act (1996) and the

Pollution Control Act (1981) to regulate offshore CO₂

injection. These laws, later supplemented by detailed technical and

environmental regulations in the 2000s and 2010s, created the first

functioning CCS permitting system in the world and demonstrated how

existing petroleum legislation could be adapted for permanent

CO₂ storage 3-5. Onshore capture facilities are

further regulated under the Energy Act, land-use planning rules and

general environmental permitting regimes, whereas CO₂

pipelines and associated offshore infrastructure are increasingly

governed by CCS-related legislation. The cumulative effect of this

multi-layered framework is that any CCS project in Norway must

secure a petroleum-type license for reservoir access and use, a

pollution control permit for injection and storage, conventional

permits for capture installations and transport infrastructure, and

the necessary approvals for closure and post-closure monitoring,

reflecting an effective petroleum-environmental regulatory model

that has influenced CCS legislation worldwide.

The United States developed a federal regulatory framework for CCS

beginning with foundational environmental laws, such as the

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 and the Safe

Drinking Water Act (SDWA) of 1974. A significant regulatory

development occurred in 2010, when the Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA) introduced the Class VI well requirements under the

Underground Injection Control program 6. These

regulations set stringent standards for geological storage,

monitoring, and financial assurance. In parallel, CCS capture

facilities are generally required to obtain permits under the Clean

Air Act and state-level air quality regulations. CO₂

pipelines may be regulated as hazardous liquid pipelines and

therefore require authorisations under federal pipeline safety

regulations and, in many cases, certificates or permissions from

state public utility commissions, especially where eminent domain

or common carrier status is involved. Consequently, CCS project

developers must secure both federal Class VI injection permits and

the necessary state-level approvals for storage, surface access,

and environmental protection, rendering the U.S. regulatory

framework one of the most complex and influential globally.

Around the same time, Australia advanced its own comprehensive

legal approach. The Commonwealth adopted the Offshore Petroleum and

Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006, one of the first explicit CCS

statutes globally, establishing titles for assessment, injection

and closure 7.

The European Union followed with a harmonised regulatory system

through Directive 2009/31/EC, adopted in 2009 and implemented by

Member States between 2010 and 2012 8. The Directive

introduced EU-wide standards for geological storage, monitoring,

corrective measures, financial security and post-closure

responsibility, while also integrating CCS into the EU Emissions

Trading System by deeming permanently stored CO₂ as "not

emitted". The Directive requires national transposition,

creating a consistent framework for exploration, operation,

closure, and post-closure phases of CO₂ storage. CCS projects

in the EU require environmental and industrial permits for capture

installations, CO₂ transport infrastructure, and geological

storage. Operators must provide detailed site characterisation,

modelling, and financial assurance, with a storage permit granted

only if the site poses no significant risk of leakage or harm.

Post-injection monitoring and corrective measures continue until

responsibility for the site is transferred to the state, ensuring

the permanent containment of stored CO₂. The EU's

approach marked the first international attempt to unify CCS

regulation across multiple sovereign states.

In parallel to the EU, the United Kingdom developed its own

comprehensive CCS regime through the Energy Act 2008 and the

Storage of Carbon Dioxide Regulations 2010, creating a two-step

licensing system (carbon storage license and storage permit) for

offshore CO₂ storage 9-10. The regime

differentiates between offshore geological storage on the UK

Continental Shelf and onshore capture and transport activities. For

offshore storage, the North Sea Transition Authority is the

licensing body, awarding carbon dioxide appraisal and storage

licences (CS Licences) in designated licensing rounds. These grant

exclusive rights to explore and develop a storage site, and must be

supplemented by a storage permit at the operational stage, which

authorises CO₂ injection and imposes conditions on maximum

pressure, injection rates, monitoring, financial security, and

decommissioning. Onshore, operators must secure environmental

permits under the Environmental Permitting Regulations, which cover

discharges to groundwater and emissions to air 11.

CO₂ pipelines are governed by national pipeline safety rules,

with additional consents for construction and operation, and marine

licences for seabed works where applicable. The Storage of Carbon

Dioxide (Termination of Licences) Regulations 2011 outlines the

post-closure obligations and liabilities once a storage site is

decommissioned 12. The UK's system is considered one

of the most detailed offshore storage regimes globally, closely

aligned with the North Sea decarbonisation efforts.

Similarly, South Korea is transitioning from policy-based

governance to a statute-based system with the CCUS Act,

which took effect in February 2025 13. The CCUS

Act regulates CO₂ capture, transport, storage, and

long-term management as part of the country's carbon neutrality

goals for 2050.

Finally, developing economies are now adopting specialised CCS

regulation, with Indonesia issuing Presidential Regulation No.

14/2024. This act authorises CO₂ collection, transport and

storage, allows up to 30 percent of capacity for imported

CO₂, and integrates CCS with the country's oil and gas

framework, while AMDAL environmental assessments (established in

the 1990s and updated in 2021) govern environmental

approvals.

Strategic Direction and Legal Framework for CCUS in

Kazakhstan

Although Kazakhstan does not yet have a dedicated law regulating

CCUS, the strategic direction clearly recognizes CCUS as a crucial

component for achieving the country's decarbonisation goals.

The Government of Kazakhstan has outlined these objectives in its

national strategy, which serves as a foundation for future

legislation and regulatory measures.

The Strategy for Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2060 envisions

systematic development of carbon capture, utilisation and storage

technologies 14. Kazakhstan aims to reduce greenhouse

gas emissions by 50 percent by 2030 and by 95 percent by 2060

relative to 1990 levels, increase the share of renewable energy to

50 percent of the national energy mix, modernise energy and

industrial infrastructure, and accelerate the deployment of

low-carbon and climate-resilient technologies.

The strategy focuses on three main pillars of Kazakhstan's

low-carbon transition:

- decarbonisation of fossil fuel industries and processes,

- decarbonisation of non-fossil-fuel industries, and

- expansion of natural carbon sinks, coupled with the development of industrial technologies for carbon capture, utilisation, long-term storage, and sequestration.

Particular attention is given to the energy and industrial

sectors, which account for the majority of national emissions. In

the medium and long term, Kazakhstan plans to implement CO₂

capture and storage technologies at coal-fired power plants that

will remain operational beyond 2035. Decommissioned units will be

granted priority to participate in the development of renewable or

other "green" energy projects. In parallel, the

industrial sector is expected to adopt zero-emission production

technologies combined with CCUS solutions, expand recycling

efforts, and integrate alternative low-carbon materials.

Although CCS operations are not explicitly addressed in

Kazakhstan's existing legal framework, the Environmental Code

does reference "carbon dioxide capture" as an activity

requiring permits, classifying such installations as Category I

hazardous facilities. This reference may indicate the regulatory

system's preparedness to accommodate CCUS technologies, laying

the groundwork for the future development of a comprehensive legal

framework for CCUS.

Drawing from the experiences of other countries, Kazakhstan may

follow a model similar to Norway's early approach, utilising

existing subsoil use legislation to regulate CCUS activities in its

initial stages.

Applicability of Current Kazakh Subsoil Use Legislation to

CO₂ Storage

Kazakhstan's Subsoil Use Code does not directly regulate CCUS.

As a result, implementation of storage projects may require

applying general subsoil regulations by analogy. Kazakhstan

mandates licences for any type of subsoil use, but the law does not

expressly envision a licence category for CO₂ storage.

Consequently, developers must consider which form of subsoil

licence could lawfully cover CO₂ injection.

The first theoretical option involves licensing

underground storage facilities for oil, gas and related products

under Article 249(1) of the Subsoil Use Code 15.

However, this provision is inapplicable to CCS because it concerns

only man-made storage facilities for hydrocarbons,

not geological formations, and therefore cannot be interpreted to

cover CO₂.

The second option, under the Article 249(2), allows a

licence for the placement or operation of underground sites for the

storage or disposal of liquid waste, hazardous substances or

industrial effluents injected into the subsoil. This provision

appears to be the most legally feasible route for CCS, as injection

of CO₂ into geological formations could be viewed as the

storage or disposal of liquid substances into the subsoil. The term

"underground sites" is not defined in the Code, but

Article 16 describes subsoil space as a three-dimensional

geological environment available for industrial use, suggesting

that natural reservoirs may fall within its scope.

Depending on the geological target formation, further permits may

be required:

- If CO₂ is injected into depleted oil and gas reservoirs, additional regulatory uncertainty arises. The Ministry of Energy may require a hydrocarbon operations licence for enhanced oil recovery activities. Whether such a licence applies to CCS operations without hydrocarbon extraction requires a project-specific assessment.

- If injection is performed into deep saline aquifers, two permits may be required: first, a subsoil use licence issued by the Ministry of Industry and Construction (MIC), and second, a special water-use permit issued by the Ministry of Water Resources, because saline aquifers constitute water bodies subject to water regulation.

Application of this provision is contingent upon CO₂ being

formally recognised as "waste" for

regulatory purposes. This is where a key uncertainty arises:

current Kazakh legislation does not expressly designate CO₂

as waste. Under Article 317 of the Environmental Code, waste

includes any material that an operator recognises as waste or must

dispose of by law 16. CO₂ separated from flue gas

after capture might fall within this definition, unless regulators

clarify otherwise.

If CO₂ is recognised as waste, the operator must comply with

waste management requirements, including notification, permitting

and documentation under Section 19 of the Environmental Code. If

CO₂ is classified as hazardous waste, a separate licence for

hazardous waste recovery and removal will be required.

Conclusion

Having examined the potential legal mechanisms for implementing

CCUS projects in Kazakhstan, we may conclude that, despite the

absence of a dedicated regulatory framework, the existing system of

subsoil, environmental and water legislation provides a minimal yet

workable basis for launching pilot projects. At this stage, the

most realistic and legally supportable approach appears to be

obtaining a subsoil-use licence for the injection of liquid

substances under Article 249(2) of the Subsoil Use Code,

supplemented by a special water-use permit when operating with deep

saline aquifers. Where depleted oil and gas reservoirs are used, an

additional assessment may be required to determine whether

licensing for hydrocarbon-related operations is triggered.

The further development of CCUS in Kazakhstan faces several

unresolved legal uncertainties that are critical for project

structuring and investment decision-making. The central issue

concerns the legal classification of CO₂ in whether it should

be treated as "waste" and if so, at what stage of the

technological process. Current legislation does not expressly

designate CO₂ as waste, but under certain conditions captured

CO₂ may fall within the definition of waste provided in

Article 317 of the Environmental Code. Such recognition would

trigger the full scope of waste-management requirements, including

licensing, notifications, permitting procedures and where

applicable, compliance with the rules governing hazardous

waste.

The correct determination of CO₂'s legal status directly

affects the applicability of Article 249(2) of Subsoil Use Code,

the potential qualification of subsurface injection as

"disposal" or "storage" of liquid waste, the

need for water-use authorisations, and regulatory obligations

relating to monitoring, reporting and long-term liability for the

storage site. The lack of a clear statutory position on these

matters creates significant risks for investors and operators,

including uncertainty regarding the appropriate permitting pathway,

operational regime, allocation of responsibilities between the

state and the project developer, and the scope of future monitoring

and remediation obligations.

Kazakhstan's strategic documents demonstrate a strong

commitment to developing a comprehensive regulatory framework that

will enable the large-scale deployment of CCUS technologies. The

current state policy positions CCUS as a critical element in the

country's energy and industrial transformation, aligning with

the national objectives of carbon neutrality. To facilitate this

transition, further development of the legal framework is

essential. Key areas include the formal classification of

CO₂, defining permitting requirements, addressing long-term

liability and monitoring obligations, and clarifying the

interaction of CCUS activities with water and waste legislation.

Resolving these issues will be key to attracting investment,

reducing regulatory uncertainty, and supporting Kazakhstan's

success in achieving its long-term carbon-neutrality goals.

Footnotes

1 Global Status of CCS report. Global-Status-of-CCS-2025-report-9-October.pdf

2 UNECE. Carbon Capture, Use and Storage (CCUS). https://unece.org/sustainable-energy/cleaner-electricity-systems/carbon-capture-use-and-storage-ccus

3 Regulations relating to documentation in connection with storage of CO2 on the shelf. https://www.sodir.no/en/regulations/regulations/materials-and-documentation-in-connection-with-surveys-for-and-utilisation-of-subsea-reservoirs-on-the-continental-shelf-to-store-co/

4 Regulations relating to exploitation of subsea reservoirs on the continental shelf for storage of CO₂ and relating to transportation of CO₂ on the continental shelf. https://www.sodir.no/en/regulations/regulations/exploitation-of-subsea-reservoirs-on-the-continental-shelf-for-storage-of-and-transportation-of-co/

5 CO₂ safety regulations. https://www.havtil.no/contentassets/85219a8bda32464a97e024d6be29cdba/co2-sikkerhetsforskriften_e-2.pdf

6 Underground Injection Control Program. https://www.epa.gov/uic/underground-injection-control-regulations

7 Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006. https://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/opaggsa2006446/

8 Directive 2009/31/EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/31/oj/eng

9 Energy Act 2008. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/32/contents

10 Storage of Carbon Dioxide Regulations 2010. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/2221/contents

11 Environmental Permitting Regulations. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2016/1154/contents

12 Storage of Carbon Dioxide (Termination of Licences) Regulations 2011. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2011/1483/contents

13 CCUS Act. https://climate-laws.org/document/act-on-the-capture-transportation-storage-and-utilisation-of-carbon-dioxide_ce05

14 Strategy for Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2060. https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/U2300000121

15 Subsoil Use Code. https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K1700000125

16 Environmental Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K2100000400

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.