- within Privacy topic(s)

- within Privacy topic(s)

- in European Union

- with readers working within the Consumer Industries, Technology and Law Firm industries

"It's just data. And they're collecting it anyway."

That was my friend's casual response when I asked about the data their smart ring was measuring—heart rate, pulse, and other health metrics. At first glance, many consumers see data in a one-dimensional way—just text/numbers on a screen, and they may not give much thought to how that data is processed, shared, or even monetized.

But what if that data is more than just numbers? What if it qualifies as personal data, which is data linked or reasonably linkable to an identifiable individual? This is the moment when many consumers to take a closer look— especially when they learn that their data could be sold to third parties.

Recognizing the risks, states across the U.S. are stepping in to protect consumer data privacy. In this article, we will examine the growing landscape of state-level data privacy laws, and explore how different states are taking action to protect their residents' personal data.

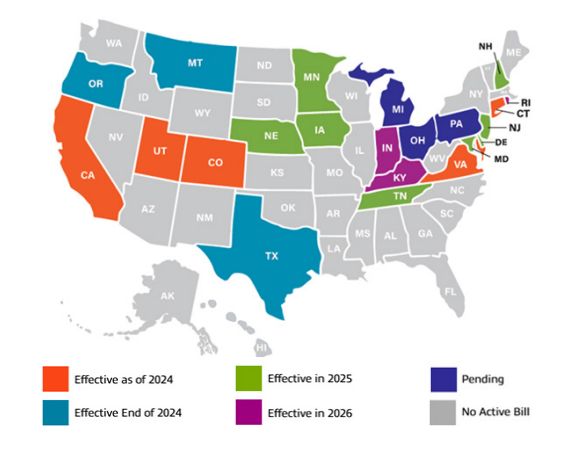

The Drumbeat of Change in U.S. Privacy Laws

Since the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) went into effect in 20201 and the addendum California Privacy Act (CPRA) which went into effect in 20232 , data privacy legislation has gained significant traction across the United States, with 18 states now having passed comprehensive privacy laws. These laws typically adhere to a shared framework, which includes setting applicability thresholds, specifying exemptions for certain entities or data types, defining consumer rights over personal data, and outlining businesses' obligations such as privacy notices, data minimization, and data protection requirements.

On the face of it, these laws may appear similar; however, a closer examination reveals significant divergences, reflecting the growing trend of states adopting distinct and at times conflicting approaches to data privacy regulation.

The following sections highlight key distinctions among various state data privacy laws but do not provide an exhaustive comparison of all applicable provisions. It is imperative to thoroughly review the specific requirements of each state law to ensure compliance for your business or client.

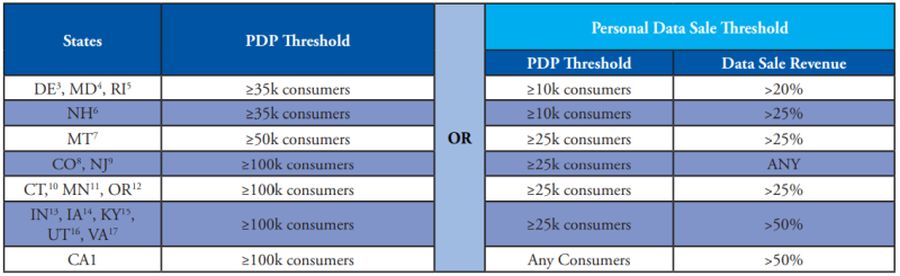

Each U.S. state's privacy law establishes specific applicability criteria, typically defined by an entity's jurisdiction, revenue, data processing volume, and revenue derived from selling personal data. Most states require entities to meet either a personal data processing (PDP) threshold or personal data sale threshold including a PDP threshold and data sale revenue, which is the amount of the entity's gross revenue that is generated from the sale of personal data. (See graphic below.)

Exemptions

All consumer privacy laws further set out exemptions, carving out specific entities and/or data types from compliance requirements. While a broad consensus exists in exempting government agencies, Colorado diverges by offering exemptions at the data level rather than outright entity-level exclusions.

Most states exclude nonprofit organizations and higher education institutions from their privacy statutes, but a growing number apply limited or no exemptions at all. Some key state-specific variations include:

- Nonprofits: Not exempt in Colorado, Minnesota, and New Jersey

- Higher Education Institutions: Required to comply in California, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Oregon.

- Delaware: Exempts only nonprofits serving victims or witnesses of child abuse, domestic violence, human trafficking, sexual assault, violent felonies, or stalking

- Maryland: Exempts only nonprofits that process or share personal data exclusively to assist law enforcement in investigating criminal or fraudulent insurance-related acts or to support first responders handling catastrophic events.

- Montana: Exempts only nonprofits engaged in detecting insurance fraud.

- Oregon: Limits exemptions to nonprofits focused on preventing insurance fraud and journalistic nonprofits.

Beyond exclusion of specific institutions, most states incorporate data-level or a combination of data and entity level exceptions to data governed by existing federal regulations. Frequently exempted data categories include those already governed by: Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability

Nebraska18 and Texas19 stand out by imposing no thresholds. Instead, companies operating within these states are subject to their privacy laws if they process any consumer personal data at all.

Act (HIPAA); Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), and Driver's Privacy Protection Act (DPPA).

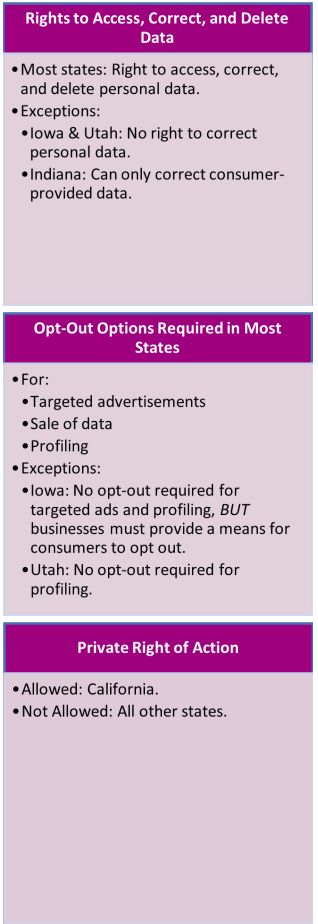

Defining Consumer Rights

Data privacy laws establish legal safeguards for individuals' personal information by granting them enforceable rights over how their data is collected, processed, and shared. These rights—including access, deletion, correction, and the ability to opt out—enable individuals to exercise greater control over their digital identities and personal information. Below is an overview of consumer rights granted under various state laws.

Business Obligation

Across all U.S. state privacy laws, regulated entities must provide consumers with clear and accessible privacy notices detailing their data practices including how personal data is collected, used, shared, and retained. However, states still vary with respect to the details provided in privacy laws. For example, while most states mandate that privacy notices disclose "all categories of third parties" with which personal data is shared, California further requires businesses to disclose—upon request—the specific third parties with whom a consumer's data has been shared.20 In addition, California stands alone in requiring privacy notices to be provided "at or before the point of collection," ensuring consumers are informed before any personal data is processed.21 By contrast, other states generally allow businesses to present these notices at later stages, such as when consumers access a company's privacy policy online.

To mitigate the risks associated with excessive data collection, all U.S. state privacy laws include some form of data minimization and purpose limitation requirements. Data minimization clauses generally require that the collection, use, retention, and sharing of personal information be limited to what is adequate, relevant, and reasonably necessary in relation to the specific purpose for which it was collected. Similarly, purpose limitation provisions restrict businesses from using personal data beyond its original purpose unless they obtain explicit consumer consent. However, not all states impose these constraints. For instance, Utah does not include data minimization or purpose limitation requirements in its privacy laws.

Status of Data Privacy in Michigan

In 2023, Michigan's Senate introduced Senate Bill SB0659, known as the Michigan Personal Data Privacy Act22. If enacted, the Act would establish comprehensive data privacy protections. Similar to laws in Colorado and New Jersey, the Act would apply to businesses that either:

- Control or process the personal data of at least 100,000 consumers; or

- Control or process the personal data of at least 25,000 consumers and derive any revenue from the sale of personal data.

A notable distinction in Michigan's bill is the explicit exemption for data collected for automated driving systems. Specifically, "[i]nformation or data that are collected or obtained for the sole purpose of developing, testing, or operating an automated driving system or advanced driver assistance system in a motor vehicle."23 This exemption underscores Michigan's longstanding role as an automotive hub, ensuring that data collected for vehicle automation remains outside the scope of the state's privacy regulations, while still restricting the use of the data to "...developing, testing, or operating an automated driving system or advanced driver assistance system."

But given the potential risks of data breaches in automotive systems, it is unlikely other states will offer the same automotive exemption currently proposed in the Michigan bill. For instance, in November 2024 it was reported that hackers were able to take control and access sensitive customer data for Subaru vehicles which were connected to its Starlink services.24 While such breaches might be exempt if the Michigan bill passes, the same breach would not be exempt under other state laws. OEMs and suppliers would therefore need to be prepared to report and handle breaches based on the numerous other state laws which don't provide the same exemption as Michigan.

Despite passing the Michigan Senate on December 12, 2024, the bill failed to be enacted before the legislative session ended on December 19, 2024. It currently remains in limbo within the Government Operations Committee in Michigan's House of Representatives. Unless reintroduced and passed in a future session, Michigan will continue to lack a comprehensive data privacy law, leaving businesses and consumers in a state of regulatory uncertainty.

Enforcement and Consumer Rights

State Attorneys General have assumed a vital role in protecting individuals' privacy rights by enforcing both longstanding and newly enacted laws.

Leading the charge is Texas, which secured a landmark $1.4 billion settlement with Meta for the unauthorized collection of biometric data, a violation of the state's Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA).25 Building on this momentum, Texas recently filed suit against Allstate and its subsidiary, Arity ("Allstate"), "for unlawfully collecting, using, and selling data about the location and movement of Texans' cell phones through secretly embedded software in mobile apps, such as Life360. Allstate and other insurers then used the covertly obtained data to justify raising Texans' insurance rates...These actions violated the Texas Data Privacy and Security Act ('TDPSA')."26

As state-level enforcement of data privacy laws intensifies, businesses should not only familiarize themselves with emerging comprehensive data privacy laws but also be aware of other state statutes that impose additional restrictions on the collection, use, and sale of personal data.

Federal Initiatives

As data privacy laws continue to diverge across the United States, there have been growing calls for a unified federal framework. Yet, despite ongoing discussions in Washington, a comprehensive federal solution remains elusive.

The latest bill, the American Privacy Rights Act (APRA) of 2024, proposes a unified approach to privacy regulation at the federal level.27 By emphasizing data minimization, privacy by design, and enhanced protections for sensitive data, the act seeks to preempt the fragmented state laws with a cohesive framework, aiming to simplify compliance for businesses while strengthening consumer rights. However, the APRA remains under review by the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, facing obstacles such as concerns over preempting stricter state laws and ongoing debates about its enforcement mechanisms.

As we wait for a federal level data privacy law, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has taken an active role in monitoring businesses collection, processing, and/or use of personal data under the banner of "unfair and deceptive practices" codified in Section 5 of the FTC Act (15 U.S.C. 454).28

Recently, the FTC has ramped up enforcement against unfair and deceptive digital practices, focusing on sensitive data misuse. A key shift was the agency's increasing use of unfairness claims to combat privacy violations. For example, earlier this year, the FTC issued an action against General Motors and OnStar alleging the companies "...collected, used, and sold drivers' precise geolocation data and driving behavior information from millions of vehicles—data that can be used to set insurance rates—without adequately notifying consumers and obtaining their affirmative consent."29 In a proposed order to settle the action, the companies are banned "...for five years from disclosing consumers' sensitive geolocation and driver behavior data to consumer reporting agencies. They also must take other steps to provide greater transparency and choice to consumers over the collection, use, and disclosure of their connected vehicle data."30

In addition to the FTC's enforcement action, General Motors is also facing lawsuits in Texas31 and Arkansas32, highlighting the growing legal consequences for businesses that improperly collect, use, or share consumers' personal data.

Looking Ahead

As regulatory scrutiny intensifies, 2025 is likely to see stricter enforcement of data minimization and privacy by design. Businesses will face greater obligations to limit data collection, processing, and retention strictly to necessary purposes, reducing excessive data use. Individual rights, including access, correction, deletion, and data portability, will become a central focus, requiring companies to implement more transparent data management practices.

Businesses must stay vigilant, be ready to adapt to new laws, and strengthen their compliance strategies to navigate this complex environment effectively.

Footnotes

1. California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), Office of the Att'y Gen. of Cal., https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa (last visited Mar. 13, 2025).

2. The CCPA was amended in 2020 when California voters passed the California Privacy Right Act (CPRA) which added new additional privacy protections that became effective on January 1, 2023.

3. Del. Code Ann. tit. 6, § 12D-103 (2024). Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act - https://delcode.delaware.gov/title6/c012d/index.html

4. Md. Code Ann., Com. Law § 14–4702 (2024). Maryland Online Data Privacy Act of 2024- https://www.cliclaw.com/library/us-state-laws/ maryland/maryland-online-data-privacy-act-2024-%E2%80 %9Cmodpa%E2%80%9D-md-commercial-law-code

5. R.I. Gen. Laws § 6-48.1-1(2) (2024). Rhode Island Data Transparency and Privacy Protection Act - https://webserver.rilegislature.gov/Statutes/TITLE6/6-48.1/INDEX.htm

6. N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 507-H:2 (2025). - https://gc.nh.gov/rsa/ html/LII/507-H/507-H-mrg.htm

7. Mont. Code Ann. § 30-14-2803 (2024). https://archive.legmt.gov/ bills/mca/title_0300/chapter_0140/part_0280/sections_index.html

8. Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1301 (2021). Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) https://coag.gov/app/uploads/2022/01/SB-21-190-CPA_Final.pdf

9. New Jersey Data Protection Act, N.J. Stat. § 56:8-240 (2024). https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/Bills/2022/PL23/266_.HTM

10. An Act Concerning Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring, 2022 Conn. Pub. Acts No. 22-15. Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA) https://www.cga.ct.gov/2022/ACT/PA/ PDF/2022PA-00015-R00SB-00006-PA.PDF

11. Minnesota Consumer Data Privacy Act, S.F. No. 2915, 93rd Leg., Reg. Sess. (Minn. 2024) Minnesota Consumer Data Privacy Act https://www.revisor.mn.gov/bills/text.php?number=SF2915&version =latest&session=ls93&session_year=2023&session_number=0

12. Rev. Stat. §§ 646A.570–646A.589 (2024). Oregon Consumer Privacy Law https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/bills_laws/ors/ ors646A.html

13. Ind. Code § 24-15-1-1 (2024). Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act - https://iga.in.gov/laws/2024/ic/titles/24#24-15

14. Iowa Code § 715D.1 (2024). Iowa Consumer Data Protection Act,- https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/code//715D.pdf

15. Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 367.130 et seq. (2024). Kentucky Consumer Data Protection https://casetext.com/statute/kentuckyrevised-statutes/title-29-commerce-and-trade/chapter-367-consumer-protection/kentucky-consumer-data-protection-act

16. Utah Code Ann. § 13-61-102 (2024). Utah Consumer Privacy Act https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title13/Chapter61/13-61-S102.html

17. Va. Code Ann. § 59.1-575 et seq. (2024). Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title59.1/chapter53/

18. Neb. Rev. Stat. § 87-1101 et seq. (2024). Nebraska Consumer Data Privacy Act https://casetext.com/statute/revised-statutes-ofnebraska/chapter-87-trade-practices/article-11-data-privacy-act

19. Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.001 et seq. (2024).-Texas Data Privacy and Security Act https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/ BC/htm/BC.541.htm

20. See CCPA Section 1798.115; https://tinyurl.com/3fzp9hfy

21. See CCPA 1798.100.

22. S.B. 659, 102nd Leg., Reg. Sess. (Mich. 2024). https://www. legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/billengrossed/Senate/ pdf/2023-SEBS-0659.pdf

23. Id.

25. David Shepardson, Meta Platforms to Pay $1.4 Bln to Settle Texas Lawsuit over Facial Recognition Data, Reuters (July 30, 2024), https://www.reuters.com/technology/cybersecurity/meta-platforms-pay-14-bln-settle-texas-lawsuit-over-facial-recognition-data-2024-07-30/

26. Press Release, Tex. Att'y Gen., Attorney General Ken Paxton Sues Allstate and Arity for Unlawfully Collecting, Using, and Selling Over 45 Million Texans' Data (July 2024), https://www. texasattorneygeneral.gov/news/releases/attorney-general-kenpaxton-sues-allstate-and-arity-unlawfully-collecting-using-andselling-over-45

27. U.S. Senate Comm. on Com., Sci. & Transp., The American Privacy Rights Act of 2024, 118th Cong. (2024), https://www. commerce.senate.gov/services/files/E7D2864C-64C3-49D3- BC1E-6AB41DE863F5.

28. Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Federal Trade Commission Act (June 2008), https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/ supmanual/cch/200806/ftca.pdf.

29. Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm'n, FTC Takes Action Against General Motors for Sharing Drivers' Precise Location & Driving Behavior Data (Jan. 2025), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/ news/press-releases/2025/01/ftc-takes-action-against-generalmotors-sharing-drivers-precise-location-driving-behavior-data.

30. Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm'n, FTC Takes Action Against General Motors for Sharing Drivers' Precise Location & Driving Behavior Data (Jan. 2025), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/ news/press-releases/2025/01/ftc-takes-action-against-generalmotors-sharing-drivers-precise-location-driving-behavior-data.

31. Press Release, Tex. Att'y Gen., Attorney General Ken Paxton Sues General Motors for Unlawfully Collecting Drivers' Private Data (Jan. 2025), https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/news/ releases/attorney-general-ken-paxton-sues-general-motors-unlawfully-collecting-drivers-private-data-and.

32. Press Release, Ark. Att'y Gen., Attorney General Griffin Sues General Motors and OnStar for Deceiving Arkansans and Unlawfully Selling Data (Jan. 2025), https://arkansasag.gov/newsrelease/attorney-general-griffin-sues-general-motors-and-onstarfor-deceiving-arkansans-and-unlawfully-selling-data/.

Originally Published by State Bar of Michigan's IPLS Proceedings, 8 May 2025

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]