Few concepts in law are as challenging as identity and privacy.

"Identity" is ubiquitous in law. It's relevant in contracts, evidence, title, intellectual property, agency, services and a host of other legal settings. The ambiguity and jurisdictional complexity of "privacy" results in complications and frictions in all sorts of communications, interactions and information-sharing arrangements.

Practicing attorneys and in-house counsel find it increasingly difficult to provide advice on privacy and digital identity issues in a world where legal authorities lag behind real-world information risks. The challenges continue to grow, as AI-fueled interactions are adopted by more individuals and organizations. How can practitioners deal with the gap between legal precedents in all jurisdictions and the potential risks upon which they provide advice? How is counsel supposed to guide corporate activity in the rapidly and continually changing face of the digital world?

We have a suggestion: functional privacy, which links yesterday's legal precedents and solutions with tomorrow's tough legal questions. The approach focuses on the degree to which a given legal structure supports the expected performance of the functions of real-world systems through which people and institutions recognize, remember and respond (3Rs) to specific people and things.

Introducing functional privacy

In short, functional privacy is the voluntary alignment of expectations about how we recognize, remember and respond to specific people and things.

This definition builds on the concept of "functional identity," which describes identity systems in terms of how they function: how identity works and how we use it. This focus on objectively testable functional metrics (the 3Rs of identity systems) harnesses the power of identity across domains and jurisdictions while also disambiguating privacy commitments. All identity systems can be described, analyzed and regulated based on how they perform the three functions of recognizing, remembering and responding to specific people and things.

By linking privacy to measurable performance elements of functioning identity systems, attorneys are better able to provide specific and actionable advice on the sorts of contractual arrangements and other structures through which people and entities can reliably and predictably reduce their risk and leverage their effects in today's networked interaction and information environments.

Functional privacy supports objective and auditable measurements through which lawyers and their clients can more confidently and consistently navigate the transitions in law and business that are driven by advances in networked information, AI and other future technologies that affect our interactions and to effectively identify, isolate and mitigate the new risks.

Setting the stage for shared expectations

Functional privacy naturally integrates legal precedents (and cultural preferences) from existing laws and across jurisdictions. Existing precedents and cultural preferences reflect and reaffirm established expectations about system functions.

By focusing on how we use identity and privacy in the real world — and how these concepts guide functionality in identity systems at present and in the future — we can naturally embrace and build on prior and current practice and precedent, reducing risk and cost for all parties. The 3Rs focus provides a logical, scalable and common-sense framing that can help manage organizational changes consistent with evolving expectations and developing legal precedent.

In prior decades, existing legal precedent has both reflected and shaped organizational 3R processes that render identity- and privacy-related functions reliable and predictable.

For example, identity authentication processes at all organizations (a.k.a. how we "recognize" each other), are shaped by local privacy and data security laws and regulations. The phenomenon of law informing organizational policies and functions continues to be reflected in the organizational function-shaping effects of technical requirements and policy imperatives compelled by identity and privacy-related laws and precedents, such as the EU's GDPR and HIPAA and Gramm-Leach-Bliley in the U.S.

However, the statutory and regulatory public law lags behind rapidly changing technologies. Advances in telecommunications and online information networks continue to transform society, yet the public law inevitably reflects a time capsule of expectations of identity and privacy frozen in precedent. The laws are not wrong but are continually rendered anachronistic by advances in technology and, in particular, advances in information-related technologies.

The faster technology advances, the more the legal precedent lags real-world functional practices. The result is a legal narrative void that provides insufficient support in helping to establish shared expectations about system and organization function performance expectations in the gap between fast-moving technical practices and slow-responding law.

Risk emerges in the absence of shared expectations

Functional privacy focuses attention on dynamic party expectations regarding identity (3R) interactions and asks what is needed to satisfy those expectations — in the absence of coherent legal precedent. When party expectations about 3R activities are explicitly managed, in business, operating, legal, technical and social domains, the degree to which those expectations are shared offers the foundation for agreement and the degree and ways in which party expectations vary inform topics for clarification and negotiation by the parties.

In this way, functional approaches documented in contracts provide a bridge from past precedent (and expectations) to future shared expectations and best practices. The contractual duties established in contracts (whether bilateral, multilateral or mass contracts) help to fill the duties gap between law and technology. It is from duties (whether established by contract or public law) that all rights are made legally cognizable and realizable. Privacy rights, without corresponding actionable duties, are merely words on paper.

Risks arise when the functions of 3R systems don't meet the expectations of one or more parties to an interaction. The meeting of the minds in a well-prepared contract represents the alignment of party expectations and a minimization of risks to the parties. When expectations about the performance of elements of any 3R systems are not aligned, risk arises for both parties.

Functional privacy invites attorneys and their clients to incrementally and specifically reduce risk by focusing on detailed functional aspects of operational identity systems in a given context, jurisdiction and culture, and documents those expectations in terms of rights and duties in agreements and education. When systems operate across borders, languages and contexts, functional analysis of identity systems helps identify anomalies to be addressed in contracts — either directly through performance service-level agreement terms, representations and warranties (for known risks), etc., or indirectly (for unknown risks) through mechanisms of indemnity, insurance, etc.

Functional privacy frames all interactions among people, organizations and inanimate things, not just interactions among humans, further amplifying its potential for applications in legal analysis and advice. The broad application and the focus on expectations enable scaling of application, while the focus on objectively measurable expectations of performance of identity systems enables accountability and enforcement of expectations across myriad formerly isolated domains. The ability to deliver localizable scale and accountability hints at the potential power of the functional approach.

Functionality puts legal counsel in the position to identify and document their clients' expectations in contracts and other legal arrangements from which their respective identity and privacy requirements can be more efficiently satisfied.

Understanding the 3Rs

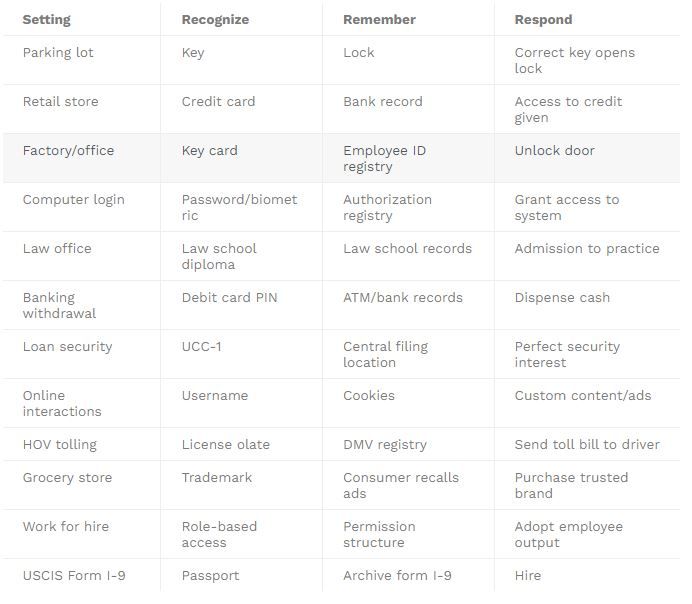

The 3Rs may initially sound mysterious, but a few examples reveal how familiar they are, particularly in legal practice. In fact, most (and possibly all) of the interactions that lawyers deal with can be usefully categorized as being associated with recognizing, remembering, and responding among entities.

System elements through which an entity recognizes another entity are pervasive in commercial and social circles and are foundational to trust in those systems. Systems of procurement and inventory management, qualification/certification, value transfer, evidence rules and a host of others all implement different mechanisms for recognition.

Authentication systems are recognition systems that connect a current participant with a known record. We regularly do this with usernames and passwords, credentials, biometrics and cryptographic challenges. In fact, the levels of assurance (LOA) concept reflects different levels of expectations of parties associated with different risks in interactions. As noted previously, the functional approach comprises a new framing, but it reflects myriad practices, including systems for recognizing, that are as old as society itself.

The systems through which humans and other entities remember each other are evidenced throughout social systems and the legal systems that they depend on. Systems of membership, land title, professional certification, employment, payment, warehousing, banking, voting, supply chains and a host of others all depend on systems to reliably remember their relationship to other entities.

Land title is a system of reliably and intergenerationally remembering who owns land. The 3Rs approach even helps to analytically position new types of interactions. Consider, for example, that blockchain technologies underlying bitcoin are distributed ledgers that are intended to create decentralized systems of collective remembering to prevent double spend.

Finally, systems of responding include all manner of mechanisms for interaction and communication, many of which are shaped by legal considerations. For example, how a company uses stored (remembered) information to respond to customers and other recognized parties is affected by a host of laws and regulations relating to data usage and security, consumer protection, payment processing, advertising rules, sectoral regulation, FTC applications of trade law, anti-discrimination laws, state privacy laws and a host of other legal considerations.

In short, responding is how any computational or cognitive system uses identity information to moderate or provide services. A functional approach can help frame emerging risks. For example, use of artificial intelligence to respond to customers creates new legal and financial liabilities. Proposals to provide notice to consumers about AI usage in commercial contexts (such as in online services, chat functions, advertising, advice, etc.) are intended to help assure that recipients of communications are aware of the source of the responses they receive and to protect themselves accordingly. Such notice is just one way a firm might establish an alignment of expectations with its counterparties.

Examples of 3R framing of everyday identity and privacy system functions

There is a growing global trend and aspiration in privacy laws to provide individuals with greater control about whether and how their personal information is shared and sold, which invites that companies better respond to consumer choices.

The application of functional privacy focuses attention on the measurable and auditable performance of identity systems across a variety of business, operating, legal, technical and social considerations and can help attorneys and their clients to respond to this trend and have greater insight into the degree of reliability and predictability and overall integrity of networked information systems, even as those systems continue their torrid rate of growth fueled by network effects and AI.

The functional approach and the 3R framing of identity provide greater leverage in strategies for future interactions and a basis upon which to mitigate risks with greater confidence.

Co-authored by Joe Andrieu founder and CEO of Legendary Requirements, a tech consultancy focused on requirements engineering for decentralized identity and Scott David, J.D., LL,M., is director of the Information Risk and Synthetic Intelligence Research Initiative at the University of Washington Seattle's applied physics laboratory.

Originally published by The Patent Lawyer in Corporate Compliance Insights, 22 July 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.