Holding:

In Mylan Pharms. Inc. v. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., No. 21-2121 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 29, 2022), the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ("the Federal Circuit") affirmed the Final Written Decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board ("the Board") upholding the claims of U.S. Patent No. 7,326,708 ("the '708 patent") challenged in IPR2020-00040.

Background:

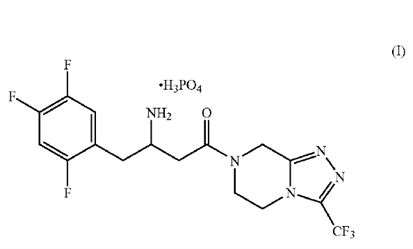

The '708 patent describes sitagliptin dihydrogenphosphate ("sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt") or a hydrate thereof, a dipeptidyl peptidase-IV ("DP-IV") inhibitor which can be used for treating non-insulin-dependent (i.e., Type 2) diabetes. Claim 1 of the '708 patent reads:

- A dihydrogenphosphate salt of a 4-oxo-4-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6-dihydro[1,2,4]tria-zolo[4,3-a]pyrazin-7(8H)-yl]-1-(2,4,5-tri-fluorophenyl)butan-2-amine of Formula I:

or a hydrate thereof.

Dependent claim 2 recites the (R)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt, dependent claim 3 recites the (S)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt, and dependent claim 4 recites a crystalline monohydrate form of the (R)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt. Id. at *3.

Mylan challenged several claims of the '708 patent, including claims 1-3, as anticipated by WO 2003/004498 ("the '498 publication"), which is owned by Merck and is the equivalent of U.S. Patent 6,699,871 (collectively "Edmonson"). Id. Edmondson discloses a genus of DP-IV inhibitors and 33 species, one of which is sitagliptin. Id. Edmondson also discloses that pharmaceutically acceptable salts can be formed using one of eight "[p]articularly preferred" acids, and names phosphoric acid as a particularly preferred acid. Id. Finally, Edmonson discloses that the salts may exist in crystalline forms, including as hydrates. Id. at *3-4.

Mylan also argued that several claims of the '708 patent, including claims 1-4, would have been obvious over Edmondson and two additional publications, Brittain and Bastin. Id. at *4.

Board:

According to the Board, Mylan did not show that the claims of the '708 patent were anticipated because there was "no express disclosure of all of the limitations of the 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt in Edmondson," and Mylan could not fill in the gaps by arguing that one of ordinary skill in the art would "at once envisage" what is missing. Id. at *5. Inherent anticipation was ruled out because the evidence "showed that 1:1 sitagliptin DHP does not form every time sitagliptin and DHP were reacted." Id.

With respect to obviousness, the Board concluded that Merck was able to antedate Edmonson with respect to the subject matter of certain claims, including claims 1 and 2, drawn to sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt or a hydrate thereof and to the (R)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt or hydrate thereof, respectively. Specifically, the Board determine that Merck had reduced to practice at least as much, and in fact more, of the claimed subject matter than was shown in Edmondson. Id. By antedating the claimed subject matter, "Edmondson was not a 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) reference, but merely a 35 U.S.C. § 102(e) (pre-AIA) reference." Id. Since the '708 patent and the subject matter of Edmondson were commonly owned by Merck at the time of the invention, the 35 U.S.C. § 103(c)(1) (pre-AIA) exception applied. Id.

Claims 3 and 4, reciting the (S)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt or hydrate thereof and a crystalline monohydrate form of the (R)-sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt respectively, were argued separately. The Board concluded that, since neither Edmondson nor Bastin "disclosed anything related to (S)-sitagliptin or even a racemic mixture of any sitagliptin salt," Mylan did not show that claim 3 would have been obvious. Id. at *6. Claim 4 also survived because the Board also found that Mylan provided no rationale to explain why one of ordinary skill would have been motivated to make the claimed crystalline monohydrate form of 1:1 (R)-sitagliptin DHP of claim 4 with a reasonable expectation of success. Id.

Federal Circuit:

The Federal Circuit affirmed; the Board's conclusions that Mylan did not show the challenged claims were unpatentable for anticipation or obviousness were supported by substantial evidence. Id. at *15.

No Express Disclosure

Mylan alleged that the Board erred in finding that Edmondson's disclosure did not anticipate Merck's claim 1-3, 17, 19, and 21-23. Mylan had alleged that Edmondson's disclosure of sitagliptin as one of 33 compounds and of acids forming "pharmaceutically acceptable salts," including phosphoric acid in a list of eight "particularly preferred" acids effectively disclosed 1:1 sitagliptin DHP and thus anticipated Merck's claims.

The Federal Circuit held that the Board reasonably concluded that Edmondson does not expressly disclose 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt and that its conclusion was supported by substantial evidence. Id. at *9. The Court cited the Board's reliance on Mylan's expert's testimony that nothing in Edmondson would have directly a skilled artisan to sitagliptin in the list of 33 compounds. Id. The Court also noted that nothing in Edmondson would have directly a skilled artisan to phosphoric acid or a phosphate salt of any DP-IV inhibitor and that the list of "pharmaceutically preferred" salts comes 44 pages earlier in the specification. Id.

No Inherent Disclosure

The Federal Circuit agreed with Merck that the Board did not err in determining that Edmondson does not inherently disclose a 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt. Id. at *9.

Mylan asserted that one of ordinary skill would "at once envisage" a 1:1 stoichiometry of the sitagliptin DHP salt because (a) Edmondson disclosed an example of sitagliptin hydrochloride salt ("sitagliptin HCl") having a 1:1 stoichiometry and (b) experimental data showed that that only a 1:1 sitagliptin:DHP stoichiometry forms under conditions allegedly similar to those disclosed in Edmondson. Id. at *8.

Merck disagreed, noting that "the combined list of 33 compounds and eight preferred salts, taking into account various stoichiometric possibilities, would result in 957 salts, some of which may not even form under experimental conditions." Id. at *8. The Federal Circuit agreed that this does not meet the standard set by the "at once envisage" theory from In re Petering. Id. at *8. In re Petering held that "the prior art may be deemed to disclose each member of a genus when, reading the reference, a person of ordinary skill can 'at once envisage each member of this limited class.' In re Petering, 301 F.2d 676, 681 (C.C.P.A. 1962)." Id. at *7.

According to Merck, "Mylan seeks to expand the [In re Petering] theory inappropriately, improperly focusing on whether skilled artisans could have envisaged 1:1 sitagliptin DHP among the members of the class instead of envisaging each member of the disclosed class." Id. at *8. The Federal Circuit agreed and held that:

In re Petering stands for the proposition that a skilled artisan may "at once envisage each member of [a] limited class, even though the skilled person might not at once define in his mind the formal boundaries of the class." 301 F.2d at 681 (emphasis added). The key term here is "limited."

Id. at *9. The Federal Circuit held that 957 salts, some of which may not exist, "is a far cry from the 20 compounds 'envisaged' by the narrow genus in Petering." Id.

The Court explained that "[w]e cannot provide a specific number defining a 'limited class'.... It depends on the 'class.'" Id. Noting that Mylan's own expert admitted that salt formation is an unpredictable art that requires a "trial and error process," the Court held that the Board did not err in finding that a class of 957 predicted salts that may result from the 33 disclosed compounds and eight preferred acids, some of which may not even form under experimental conditions, is "insufficient to meet the 'at once envisage' standard set forth in Petering." Id. at *10.

Merck Antedated Edmondson's Disclosure

Mylan challenged the Board's finding that Merck had antedated Edmondson with respect to the subject matter of claims 1, 2, 17, 19, and 21–23. Id. at *11.

It was undisputed that Merck had reduced (R)-sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt to practice before Edmondson was published. Id. at *10-11. Mylan challenged the Board's determination that Merck's reduction to practice of the salt could serve to antedate Edmondson, which Mylan maintained disclosed hydrates of sitagliptin. Merck had not made hydrates until after Edmondson's publication date.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that Edmondson did not disclose sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt and thus the Board's finding that Edmondson did not disclose a hydrate of that salt was supported by substantial evidence. Id. at *12. Accordingly, Merck's reduction to practice of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt was "more...than what is shown in [Edmondson] for the claimed subject matter" and sufficed to antedate the subject matter of claims 1, 2, 17, 19, and 21–23. Id. (internal citation omitted).

Accordingly, Edmondson was a 35 U.S.C. § 102(e) reference, rather than a 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) reference with respect to claims 1, 2, 17, 19, and 21–23. Id. at *10-12. Since Merck commonly owed both the inventions claimed in the '708 patent and the subject matter of Edmondson at the time of the invention, the Board properly determined that the 35 U.S.C. § 103(c)(1) (pre-AIA) exception applied to claims 1, 2, 17, 19, and 21–23. Id.

Mylan Failed to Show Claims 3 and 4 Would Have Been Obvious

The Federal Circuit agreed that substantial evidence supported the Board's decision that Mylan failed to show that claim 3, drawn to the (S)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt, and claim 4, drawn to a crystalline monohydrate form of the (R)-configuration of the sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt would have been obvious. Id. at * 13.

The Federal Circuit noted that the Board found that there was no motivation to combine Edmondson and Bastin to make sitagliptin DHP, that the combination of the references did not provide motivation to make (S)-sitagliptin, and that there was no reasonable expectation of success in combining the references. The Court noted with approval the Board's reliance on Mylan's expert's admission that (S)- sitagliptin DHP 1:1 salt was not disclosed in Edmondson. Id. at *14 (internal citation omitted). The Court also noted the Board's conclusion that "the general disclosure on diastereomers in Edmondson encompasses millions of potential compounds and salts with no motivation to make the (S)-enantiomer with a reasonable expectation of success, particularly in an unpredictable activity like salt formation." Id. at *14 (internal citation omitted).

The conclusion that Mylan failed to show that claim 4 was obvious was supported by Mylan's expert's testimony that a person of ordinary skill in the art "couldn't predict with any degree of certainty" hydrate formation. The Federal Circuit also favorably noted the Board's reliance on evidence of the numerous down-sides of hydrates reported in the literature and on testimony from Merck's expert that a skilled artisan would have sought to avoid hydrates and that forming crystalline salts, including hydrates, is highly unpredictable. Id. at *14.

Take-aways:

This case clarifies that the size of the disclosed class of species in the prior art that is sufficient to amount to an anticipating disclosure of each member of the disclosed class under the "In re Petering" theory is not fixed but depends on the nature of the subject matter at issue. Unpredictability and enablement are relevant considerations, in addition to the number of constituents of the class. Furthermore, the focus of the inquiry is whether a person of ordinary skill could have at once envisaged each member of the disclosed class, not whether the claimed compound could have been envisioned from within the disclosed class.

With respect to obviousness, it is important for patent owners to push back on examiners or opponents using hindsight. Often times, particularly with the aid of hindsight, the art appears combinable or modifiable in a manner that will yield the claimed invention. But hindsight cannot be a basis for obviousness. Using an applicant's disclosure as a blueprint to reconstruct the claimed invention from isolated pieces of the prior art contravenes the statutory mandate of Section 103, which requires judging obviousness at the point in time when the invention was made (or, for applications governed by the post-AIA version of Section 103, just before the filing date). See Grain Processing Corp. v. American Maize-Prods. Co., 840 F.2d 902, 907 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

See also Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Sandoz, Inc., 678 F.3d 1280, 1296 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ("The inventor's own path itself never leads to a conclusion of obviousness; that is hindsight. What matters is the path that the person of ordinary skill in the art would have followed, as evidenced by the pertinent prior art."); Ruiz v. A.B. Chance Co., 357 F.3d 1270, 1275 (Fed. Cir. 2004) ("[H]indsight reasoning, using the invention as a roadmap to find its prior art components, would discount the value of combining various existing features or principles in a new way to achieve a new result - often the very definition of invention."); and Cardiac Pacemakers, Inc. v. St. Jude Medical, Inc., 381 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2004) ("the suggestion to combine references must not be derived by hindsight from knowledge of the invention itself.").

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.