The London Interbank Offered Rate (ICE LIBOR, often referred to colloquially as Libor) is an important interest rate benchmark. It is currently set with reference to the rate at which certain large and financially sound Libor "panel" banks indicate that they can borrow short-term wholesale funds from one another on an unsecured basis in the interbank market. The benchmark is now administered by ICE Benchmark Administration Limited (IBA)[1], which is a regulated benchmark administrator, based in the United Kingdom. Libor was previously administered by the British Bankers' Association. Various scandals concerning alleged manipulation of the benchmark led to regulation of the activity of its administration and to IBA, an independent subsidiary of Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. (ICE) (a global operator of exchanges and clearing houses and a global data and listings provider) taking on the administrator role.

Libor has served as a rate that financial instruments incorporate to establish the terms of agreement and also acts as a relative performance measure that can be used, for instance, for calculating funding costs, investment returns or, in times of crisis, for signaling deep changes in the financial environment. As a reference rate for debt instruments and derivatives in U.S. Dollars and other core global currencies, Libor has become entrenched into the world's debt capital markets and lending agreements globally. Hundreds of trillions of dollars of loans and derivatives2 use U.S. Dollar Libor as a reference rate. Libor is under a process of evolution in terms of how it is calculated, other reference rates are now becoming available and regulation, especially in Europe, will change the way in which financial institutions use benchmarks. This paper discusses implications for the lending market of these changes.

We also discuss certain of the perceived limitations in possible alternative benchmarks for U.S. Dollar Libor and discuss how that could be improved; we make these recommendations cautiously, for discussion purposes, taking into account the probable need for funding costs of banks to be included when determining a new reference rate for lending transactions, as well as the policy tensions3 that are imbedded in any rate setting structure.

A Short History of Libor

Libor has been a tremendous stabilizing influence in the world's debt capital markets, including by facilitating the standardization of financial contracts. First used in 1969, Libor developed into a uniform and widely used reference rate in subsequent decades,4 with the British Banker's Association taking on a centralizing role in 1986. The financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 sowed the seeds towards significant reforms to Libor. First, as a practical matter, prudential regulators looked over the precipice and considered the systemic weaknesses of having a single reference rate with no credible alternative or back-up, when market liquidity dried up and questions arose as to the basis on which daily rates were set and submitted. At the peak of interest rate volatility during the financial crisis, a perception of lack of creditworthiness within the interbank market (and consequential negative credit feedback loops) drove Libor to spike, and to spike in a manner that, in part, drove regulators to unleash the tidal force of quantitative easing. Libor was signaling (as a benchmark rate) that the financial markets were about to collapse. The failure of the interbank market was the canary in the coal mine, and the canary was dying. In some ways, Libor acted as it should have done in the crisis, in these respects. However, the lack of real transaction data backing up some submissions for some currencies or maturities (an inevitable by-product of paralysis in the interbank market) also became apparent to regulators.

Following the crisis, the Libor "scandal" broke. Individual panel bank submissions5 were alleged to have been inaccurate or manipulated for proprietary purposes. Even senior U.K. regulators became implicated for asking banks to change their submissions at the height of the crisis. Allegations included that panel banks had purposively underreported borrowing costs materially in order to project market strength during the financial crisis, that panel bank submissions were higher or lower than actual interbank borrowing costs of the submitting panelist and that manipulation had taken place with bank panel participants and market participants acting in concert so as to benefit from a higher (or lower) published Libor rate. Ironically, these factors, if true, arguably resulted in a stabilizing effect at a time when markets most needed it. However, the value of the Libor reference rate can be viewed as a zero-sum problem; theoretically, there is always a winner and always a loser. Any divergence from a rate derived from actual interbank transactions, whether due to bank panel manipulation, regulatory coercion or otherwise, results in positions either gaining or losing value on financial contracts that use Libor as a reference rate; we will discuss this problem further below in the context of Libor transition.

In short, the Libor scandal, together with the financial crisis and technical issues in the interbank market,6 cast doubt on the efficacy of Libor and the Libor panel process and drove financial regulatory bodies to consider reforms (e.g., the Wheatley Review of Libor (2012)) and alternatives (e.g., the Financial Statement Board (FSB) report (July 2014)). One core goal of regulators has been to anchor Libor rates to actual transactions to ensure that the rate is truly representative of market conditions. At the same time, banks have become increasingly unwilling to participate as submitting banks in Libor, due to legal and compliance risks and in light of the scandals that emerged after the last crisis. The first response to this, in the United Kingdom, was new regulation: transferring Libor from the bank market association to a regulated, independent operator and regulating both the administration of benchmarks and submission of data used in calculating benchmarks. IBA, in turn, has implemented significant improvements to Libor since the takeover.7 A view by certain regulators has been reached that the panel submission basis for Libor is likely no longer sustainable and that long term liquidity and confidence in the markets will be strengthened by reform. At the same time, IOSCO standards and the EU Benchmark Regulation ask for alternatives to be developed, so as to bring choice, competition and fallbacks to interest rates. What next?

Reformed LIBOR?

With the backdrop of the failures in the submission process and the unwillingness of banks to provide data to calculate Libor, enhancements to Libor are being actively pursued by ICE Benchmark Administration. IBA has proposed to implement a number of reforms to make Libor more transaction based, with market data being incorporated alongside panel submission data, and perhaps ultimately transitioning to a centralised calculation methodology. While these reforms will likely be gradual, a number is expected to be implemented in the shorter term through the adoption of IBA's proposed "phase 1 waterfall methodology". 8][9 This evolution of Libor will address many of the issues above. Possible risks, burdens and losses relating to the outright replacement of Libor may very well overwhelm the benefits and so upgrading and retaining Libor under a reformed framework that addresses regulatory concerns—a process started some years ago—is likely to continue. If the continuity of Libor can be preserved while implementing enhancements and reforms that address the current issues with Libor, then although Libor may cease to be technically just an "inter-bank offered rate," there will likely be no issues with interpreting the meaning of existing agreements as referring to that reformed IBA Libor rate.

A Path for Change?

Libor is currently actively published for five currencies (U.S. Dollars, Euros, Japanese Yen, Pounds Sterling and Swiss Francs)10 on various tenors. To replace Libor across such a broad array of references would require concerted effort by regulators and market participants in each currency submarket. Any such replacement first requires an alternative to be developed and for that alternative to gain traction and a sufficient track record for it to be credible. The replacement path for each currency submarket is complex. Executing an orderly transition and the value "gap" between projected Libor and projected replacement rates is the elephant in the room for many market participants. The alternative rate event horizons have been slowly coming into view, and market participants are moving from a somewhat theoretical medium-term outlook of "this too shall pass" to a short-term functional outlook of "how do we get from point A to point B without getting lost or crashing into a ditch."

SOFR—Backup Rate for US Dollar Libor: there is presently no alternative rate for Libor in U.S. Dollars. However, an alternative rate for U.S. Dollars has been selected by the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC), a group of leading market participants convened by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (the Board or FRB). This proposed alternative rate is the unpublished Broad Treasuries Financing Rate (BTFR); the committee considered but did not adopt the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's (the New York Fed or FRBNY) overnight bank funding rate (i.e., the OBFR; a volume-weighted median of overnight fed funds and eurodollar transactions of U.S.-based bank offices which is an uncollateralized interbank funding rate). The unpronounceable BTFR acronym has been subsequently renamed as the Secured Overnight Funding Rate (SOFR). The concept behind the new rate is that it is a secured overnight11 Treasuries repo rate (i.e., the interest rate paid on overnight loans collateralized by U.S. government debt; collateral that is high quality and liquid and accepted as collateral by the majority of intermediaries in the repo market). It would be anchored in actual repo transactions12 with significant average daily trading volumes (e.g., averaging above $300 billion). The New York Fed has announced that it expects to publish the rate as from early 2018.13 SOFR is observed and backward looking. This stands in contrast with Libor under the current methodology, which is an estimated forward-looking rate and relies, to some degree, on the expert judgment of submitting panel members. The technical aspects of the applicable rate have been refined by the New York Fed, and we would expect that this process of refinement may continue as regulators and market participants continue to analyze the new rate. Market adoption of this new rate is a work in progress and remains to be seen. Given that SOFR is a secured rate backed by government securities (i.e., U.S. Treasuries), it will be a rate that does not take into account bank credit risk (as was the case with Libor). SOFR is therefore likely to be lower than Libor and is less likely to correlate with the funding costs of financial institutions. While repo transactions have become one of the central pillars of the money markets and overnight interest rates play an important role in determining the yield curve, whether or not SOFR gets requisite market traction is an open question.

SOFR+: a vital component in successfully developing new U.S. dollar benchmark rates will be solving for bank funding costs and the associated spread currently included within Libor. SOFR alone does not do it. As some market participants have observed, BTFR/SOFR is lower and more volatile than Libor.14 Moreover, the variance to Libor is not static or a constant percentage. For the sake of illustration, we take the variance at the end of March 2017 which was approximately 40 bps. In our discussions with market participants they have noted that if Libor had been replaced on that date with SOFR, all relevant assets would suffer significant one time losses15 for lenders and other investors who are reliant on Libor based pricing; we note that these losses may, in part, be concentrated in the equity and subordinated tranches of CLO's. Given that reformed Libor will likely be migrating to a more transaction based methodology but without having any material delta between an outcome based on current Libor methodology, and that this modified Libor will permit a stable transition, it is not clear to us why market participants would not want to strongly support the continuation of Libor, or, in the alterative, to require that a further spread be layered on top of SOFR if SOFR is to be the backup rate.

SONIA—Backup Rate for Sterling LIBOR: in contrast to the U.S. collateralized reference rate approach, the United Kingdom and Europe are developing unsecured (i.e., uncollateralized) reference rates as an alternative benchmark to stand alongside Sterling Libor and Euribor (which is the existing interbank reference rate for Euros).16 A swaps-industry working group in the United Kingdom had proposed the development of the Sterling Overnight Index Average (SONIA). SONIA is the weighted average rate to four decimal places of all unsecured sterling overnight cash transactions brokered in London made by contributing WMBA member firms (i.e., banks and building societies) above a minimum deal size. The index is a weighted average overnight deposit rate for each business day, and each rate in the average is weighted by the principal amount of deposits which were taken on that day. The Bank of England (the BofE) is the administrator of SONIA and the BofE is in the process of reforming SONIA, and the reforms are projected to become effective in April 2018.17 A number of issues arise in extending SONIA to cover maturities other than overnight maturities.

EONIA—Backup Rate for Euribor (i.e., the euro interbank offered rate): market participants in Europe already have available an alternative unsecured interbank market rate, the Euro Overnight Index Average (EONIA) as an alternative rate to Euribor. Nonetheless, in part, because of EONIA's panel-based structure, the European Central Bank has announced that it intends to develop a new overnight reference interest rate for Euros by 2020. The announced goal is to identify and adopt a "risk-free overnight rate" and "[o]nce the [ECB] has made a recommendation on its preferred alternative risk-free rate, the group will also explore possible approaches for ensuring a smooth transition to this rate, if needed in the future." Similar issues as regards maturities arise as in the context of SONIA.

TONAR—Backup Rate for TIBOR (i.e., the Japanese Yen interbank offered rate): again, in contrast to the U.S. collateralized approach, Japan has identified the uncollateralized overnight call rate (TONAR: the Tokyo Overnight Average Rate) as its applicable replacement reference rate for Tibor (i.e., the existing interbank reference rate for Japanese Yen). This replacement reference rate is calculated and published by the Bank of Japan and is intended to be a risk-free (or near risk-free) rate. It is a transaction-based benchmark using information provided by money-market brokers.

SARON—Backup Rate for Swiss Franc Libor: the Swiss National Bank (SNB), and its national working group (NWG) on Swiss Franc (CHF) reference interest rates, has identified the Swiss Average Rate Overnight (SARON) as its replacement reference rate for Swiss Franc Libor. SARON is a Swiss stock exchange index that was launched in 2009 in conjunction with the SNB as an alternative reference rate for the CHF market. It is based on actual market transactions and prices in the Swiss repo market. As with the U.S. approach, it is a collateralized reference rate. The NWG has adopted a well signaled and coordinated approach to replacing the Swiss interbank rate for swaps (TOIS fixing). TOIS fixing was discontinued at the end of 2017 and replaced with SARON.

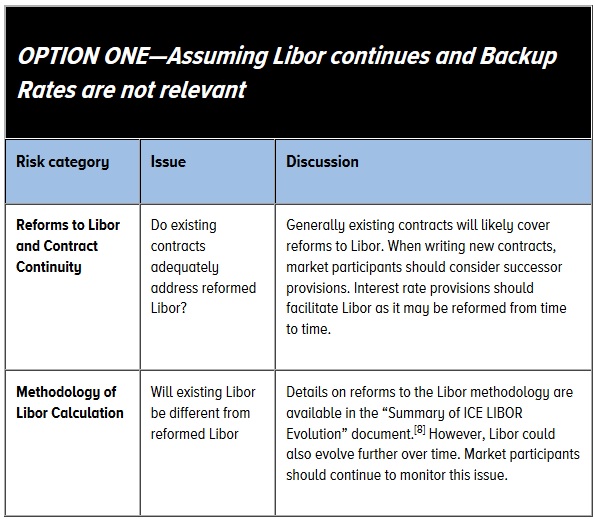

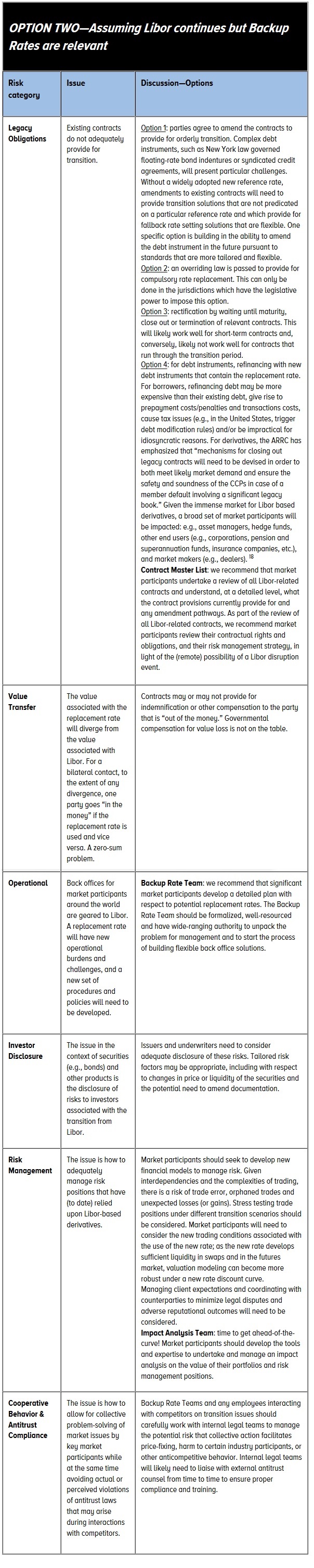

What Are Challenges in the Path Ahead?

We set forth in the tables below a high-level summary of key practical risk issues for market participants and some of the available options. Within certain options (e.g., amending legacy contracts), there are highly detailed solutions that we do not cover below.

Footnotes

1 See https://www.theice.com/iba.

2 The global derivatives markets in particular is heavily impacted by any changes to Libor. Industry groups, such as the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) and the Loan Syndications and Trading Association, are actively involved with assisting market participants and preparing for any possible changes.

3 These policy tensions include those identified by the ARRC: see generally https://www.newyorkfed.org/arrc/index.html. In addition, we take into account the standards recommended by The Board of the International Organization of Securities Commission (IOSCO) in its "Principles for Financial Benchmarks" (July 2013): see http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD415.pdf.

4 In the context of the syndicated lending market, reference interest rates, such as Libor, were initially adopted as a more transparent and cost-efficient way for banks to pass on their funding costs to their borrower clients by adding a spread to a reference rate representative of their actual funding costs. The standardization of the pass-through rate in financial contracts also led to the emergence of derivatives-based risk management, initially in the form of forward-rate agreements and then swaps and other more complex derivatives. For a current overview on U.S. dollar Libor exposures, see the following recent presentation by David Bowman (Federal Reserve Board of Governors): https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/microsites/arrc/files/2017/Bowmanpresentation.pdf.

5 A submission in response to a prospective forward-looking question: "at what rate could you borrow funds, were you to do so by asking for and then accepting interbank offers in a reasonable market size just prior to 11 a.m.?"

6 The ARRC Interim Report notes: "the secular decline in short-term unsecured wholesale funding has made the market underlying LIBOR both less liquid and much less resilient."

7 A comprehensive overview can be found here: https://www.theice.com/publicdocs/ICE_LIBOR_Roadmap0316.pdf.

8 See the Summary of ICE LIBOR Evolution document here: https://www.theice.com/publicdocs/LIBOR_evo_summary.pdf.

9 See https://www.fnlondon.com/articles/ice-benchmark-chief-libor-is-not-dead-20170811.

10 IBA has administered the production of ICE LIBOR (formerly BBA LIBOR) since early 2014. It is currently quoted for five currencies and seven maturities (from overnight to one year), resulting in the production of 35 rates on each applicable business day.

11 LIBOR has a "term" component, i.e., it is determined for the relevant quoted period (e.g., three month Libor contracts). How the market develops correlative term periods from an overnight rate (SOFR) is as yet to be determined. A critical aspect of developing these term periods based on SOFR will be creating a liquid market for interest rate swaps and futures based on SOFR. In the context of lending transactions that are based today on Libor term contracts, it is an open question as to whether or not, during the transition, there be an interim illiquidity premium and how that is to be passed through to end users (e.g., borrowers)?

12 The repurchase agreement (or repo) market is largely divisible into the bilateral repo market and the tri-party repo market. The tri-party repo market is one where dealers (i.e., asset sellers) fund their portfolio of securities through repos. At a high level, a repo is a financial transaction in which one party sells an asset to another party with a promise to repurchase the asset at a pre-specified later date. A repo is similar to a collateralized loan but its treatment under U.S. bankruptcy laws is more beneficial to the purchaser of the asset (e.g., in the context of SOFR, the buyer of U.S. Treasuries on an overnight basis; who can be thought of, by analogy, as lending cash and taking these high quality securities as collateral): in the event of the bankruptcy of the asset seller, repo asset buyers can typically sell their collateral (i.e., the sold assets; which in the context of SOFR are U.S. Treasuries), rather than be subject to the automatic stay, as would be the case for a collateralized loan. In the tri-party repo market, a third party called a clearing bank (in the United States, the market is dominated by JP Morgan Chase and The Bank of New York Mellon) acts as an intermediary and custodian, values the assets, applies a margin, settles the trades and otherwise minimizes the administrative and procedural burdens on the two underlying parties. In the context of the overnight repo market, these repos are commonly "rolled" for successive days; thereby providing ongoing cash liquidity to the seller of U.S. Treasuries. A statistical overview of the tri-party market by the New York Fed is found here: https://www.newyorkfed.org/data-and-statistics/data-visualization/tri-party-repo. A useful overview by the New York Fed of the tri-party repo market and the "wrong-way" risks for clearing banks associated with a troubled dealer is set forth here: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/2012/1210cope.pdf.

13 https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/opolicy/operating_policy_170524a.

15 To take a very simple case, if you owned $1.0 billion of unlevered Libor based loans, assuming an average weighted life to maturity of 4 years for the portfolio, you would lose $16 million if the Libor reference rate was replaced with SOFR as the reference rate and the variance was negative 40 bps. Loss calculation becomes more complex if losses on floating rate assets are matched with gains on floating rate liabilities (e.g., in the context of a CLO).

16 We note that cross-currency swap markets may suffer from lower liquidity during the Libor transition period given lack of uniformity in approach as between replacement rates and the complexity of the transition across these five major currencies.

18 Many of the forms and documents for derivatives trading are published by ISDA. Currently, ISDA documentation does provide fallback options for many of the published rates, including U.S. Dollar Libor. However, these options were primarily intended to cover short term gaps where the rate was, for various reasons, not published or otherwise available. Unfortunately, these fallback options do not adequately address the permanent discontinuance of the publication of such reference rates. Similar to other regulatory or widespread derivatives industry changes, ISDA and other industry groups have assembled working groups to address Libor-related issues. Due to the uncertainty in terms of the scope and timing of any transition, there are currently no concrete plans regarding revisions to industry standard documentation. However, there are several aspects of such documentation that will need to be addressed. Each of the ISDA documents relates to a specific set of ISDA definitions, which, for reference rates, contain the fallback mechanics. Generally, the ISDA 2006 Definitions are widely used in the market today although other versions of the definitions may be used as well. Regardless of the version of the definitions used, the fallback mechanics for each such version will have to be amended to incorporate fallback mechanics and/or a fallback rate for each of the reference rates. Any such change in fallback mechanics or fallback rate will need to be determined and generally agreed upon by both buy-side and sell-side market participants. In addition, ISDA will most likely develop a protocol that will allow market participants with existing documentation to amend these bilateral contracts to incorporate the potential new terms and/or mechanics related to the transition. ISDA, together with SIFMA, SIFMA AMG, AFME and ICMA, published a transition "roadmap" on February 1, 2018, found here: https://www.sifma.org/resources/submissions/ibor-global-benchmark-survey-transition-roadmap

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.