The PFAS Reporting Rule promulgated under the Toxic Substances Control Act ("TSCA") last year requires thousands of companies to provide data on PFAS in consumer and industrial products sold as far back as 2011.1 State laws enacted in Washington, Maine, and Minnesota also mandate reporting on the current intentional use of PFAS in any products sold in those states.2

Taken together, these regulations could present significant compliance challenges for affected businesses. Questions have already arisen about the scope of the data needed to meet the requirements under the federal and state reporting regulations, how to compile and organize PFAS chemical information for implicated products, and how to safeguard confidential information, privileged materials, and marketing strategies.

In this second part of the series on PFAS product reporting,3 we examine the challenges presented by the federal PFAS Reporting Rule as well as the reporting laws in Washington, Maine, and Minnesota. We offer suggestions that businesses may wish to consider in preparing responses to EPA and states, including building a response team, challenging reporting demands, requesting extensions, seeking protections for sensitive information, and filing public record requests.

EPA's PFAS Reporting Rule under TSCA

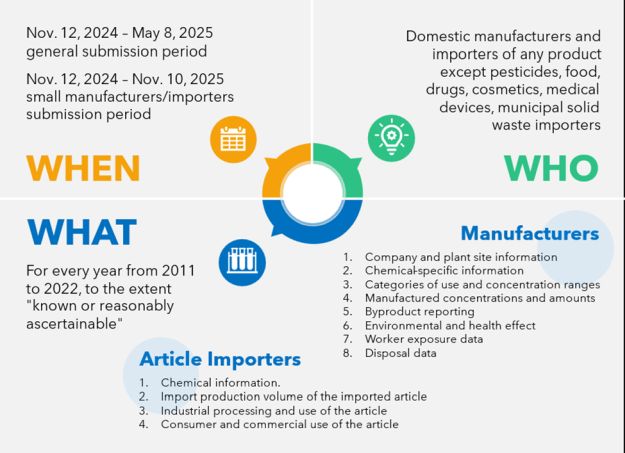

As previously described in the first article in this series, EPA's finalized PFAS Reporting Rule requires manufacturers and importers of articles containing PFAS to submit reports on intentional PFAS use in products between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2022.4

Each report must include information not only on the PFAS chemicals used in products, but also company and site information, byproducts reporting, environmental and health effects, worker exposure data, and disposal data. In order to comply with the rule, regulated parties must submit their reports during either the general submission window between November 12, 2024, and May 8, 2025; the deadline extends to November 10, 2025, for qualifying small manufacturers.5 Failures to report could result in penalties that could be in excess of $45,000 per day, per violation.6

EPA plans to make portions of the information public. Whether or not EPA makes records public on its own, submissions may become subject to public records requests under the Freedom of Information Act. EPA expects that the PFAS data it collects could potentially be used by the public, including consumers wishing to know more about the products they purchase, communities with environmental justice concerns, and government agencies seeking to reduce environmental risks. As a result, your business should consider whether to submit a confidential business information ("CBI") claim to protect submitted information. In the next article in this series, we will describe that process and considerations that may go into preparing a CBI claim.

Washington's PFAS Reporting Regime

Washington State has approached PFAS product reporting through both ad hoc reporting requests for product data from certain companies and generally applicable mandatory reporting for certain classes of products.

Under the state's Pollution Prevention for Healthy People and Puget Sound Act, passed in 2019, Washington created a regulatory framework for restricting the manufacture, sale, and distribution of "priority chemicals,"7 which could be harmful if found in "priority products."8 The statute empowers Washington's Department of Ecology ("Ecology") to identify classes of products that may contain priority chemicals and designate them for restrictions or reporting requirements in a five-year cadence.9

First, in the process of developing rules for products, Ecology can issue administrative orders under its statutory authority to review products for priority chemicals.10 These administrative orders require companies to report the following information within six months:11

- The name of the chemical used or produced and its chemical abstracts service registry number;

- A brief description of the product or product component containing the substance;

- A description of the function of the chemical in the product;

- The amount of the chemical used in each unit of the product or product component. The amount may be reported in ranges, rather than the exact amount;

- The name and address of the manufacturer and the name, address, and phone number of a contact person for the manufacturer; and

- Any other information the manufacturer deems relevant to the appropriate use of the product.

Failure to respond to a reporting order carries a maximum $5,000 penalty for a first offense, and repeat offenders are subject to up to $10,000 in penalties for each repeat offense.12

Second, Ecology can adopt a mandatory reporting framework for priority chemicals in priority products. For example, Ecology has adopted a specific framework for outdoor leather and textile furnishings starting in 2024.13 By January 31, 2025, all manufacturers of fluorinated outdoor leather and textile furnishings must either provide notice to Ecology if their products contain intentionally added PFAS, or present credible evidence that despite the presence of fluorine in their products, PFAS was not intentionally added.14 Ecology has adopted additional regulations for particular PFAS and products outside the Puget Sound Act framework.15

Critically, these records—including the orders, any communications with Ecology, and the responses—should be considered presumptively public. Most states have broad public record laws that allow any person to request a broad swath of record submissions, emails, datasets, and other documents.

Maine and Minnesota's Reporting Requirements for PFAS Products

Maine and Minnesota have passed nearly identical PFAS reporting laws with differing timelines for compliance. The laws each require manufacturers to report PFAS inputs in any products sold or offered for sale in the state.

Maine was the first state to pass a law requiring businesses to report on PFAS use in products, with an initial effective date of January 1, 2023.16 However, ongoing regulatory problems led Maine to push back the reporting deadline two years to January 1, 2025.17 Maine also adjusted its reporting standards, now allowing companies to state the PFAS content in products in terms of total organic fluorine if the amount of specific PFAS chemicals are unknown. Reporting data can also be based on supplier-provided information rather than be testing done by the manufacturer or distributor.

Minnesota's reporting law, which is coupled with a total ban on products with intentionally added PFAS by 2032, requires manufacturers to submit data on all products with intentionally added PFAS by January 1, 2026.18 Manufacturers must report on the purpose for which PFAS is used in their products, the amount of specific PFAS in products based on testing and must provide product descriptions by class of product. Manufacturers who have not reported by January 1, 2026, will be barred from selling products containing PFAS in Minnesota.19

It is not yet clear how either Maine or Minnesota plans to use these broad datasets, but any submissions could become subject to public records requests regardless of whether the states directly release reporting data to the public.

Steps Businesses May Consider When Reporting PFAS

Basic compliance with these different reporting regimes will be just the first hurdle for companies with products containing intentionally added PFAS. But beyond that, state and federal reporting mandates create the possibility that sensitive business information will be made available to the public. Public access to PFAS product reporting carries regulatory, public relations, and litigation risks. It may also disadvantage complying business by releasing sensitive information to competitors. To counteract the risks presented by reporting and protect sensitive product information, businesses should consider the following steps when approaching PFAS reporting obligations.

Build Internal and External Resources to Plan for and Respond to Reporting Needs

Businesses will need to build and leverage teams both within and outside of their organizations to respond effectively to state and federal PFAS reporting demands. Businesses should proactively connect the various stakeholders within an organization with the requisite knowledge to collect the required data. Consider designating an internal champion who will work as the point person for all things PFAS reporting. To respond effectively to varied reporting demands, people familiar with chemical composition, manufacturing history, and legal status of a product containing intentionally added PFAS will have to work together to supply the required information.

Additionally, the size and scope of current and future PFAS reporting demands can be better managed with specialized support from outside of the organization. Bringing in those with experience handling reporting under TSCA or state reporting laws can streamline and strengthen the reporting process with prior knowledge. External support may also help identify reporting gaps or issues that are for whatever reason less visible to company insiders, preventing violations and protecting valuable information.

Consider Challenging or Appealing Reporting Demands Where Reasonable

Broad reporting initiatives that apply generally to product manufacturers, such as EPA's PFAS Reporting Rule or the reporting laws passed by Maine and Minnesota, may not offer opportunities to challenge or appeal required submissions (outside the context of challenges to a rule as arbitrary and capricious or procedurally deficient). On the contrary, ad hoc administrative orders issued to compel reporting from individual companies may offer better opportunities to protect valuable data by avoiding reporting altogether.

Take Washington State as an example. To appeal or challenge an administrative order, businesses must both prepare substantive grounds for why the product or products in question should be exempt and strictly follow any procedural rules for an appeal or challenge. Successfully appealing a reporting order issued by Ecology requires a substantive showing that the identified products are not "priority consumer products" that contain PFAS. It also requires strict compliance with the procedures set out under state law, including that an appeal must be filed with the state's Pollution Control Hearings Board within 30 days of receipt of the order.20 Any appeal to the board from an Ecology order must include specific detailed information, as well as be filed on paper to Ecology itself, either by mail or in person, and the agency will not review any electronic submissions.21 For these reasons, timely engagement with experienced legal counsel is key to responding to a request for information.

Businesses are often provided advance notice that an order will soon arrive. They can take advantage of this time to prepare for the filing but can also prepare for a possible reporting order and appeal in advance by leveraging public records requests. As detailed below, businesses can access administrative reporting orders sent to peers via public records requests, giving them insight into the content and structure of the reporting orders. Public records of replies and submissions to orders could also serve to inform a company's own response strategy to a received reporting demand.

Request Extensions of Reporting Deadlines Where Available

While some reporting requirements may not offer the ability to challenge or appeal, they may still allow companies to request an extension of reporting deadlines in order to gain more time to gather the information needed for a submission or evaluate how to best safeguard sensitive data. For example, Maine's PFAS reporting law gives the Department of Environmental Protection discretion to "extend the deadline for submission by a manufacturer" upon a finding of cause.22

Assess and Build Arguments for Exemption

While federal and state PFAS reporting laws include a broad range of products, there are some categories of consumer goods that are exempt from the reporting requirements. Under EPA's TSCA reporting rule, PFAS that is produced solely for use in pesticides, food or food additives, drugs, cosmetics, or medical devices is exempt from reporting requirements.23 State reporting laws also feature limited carveouts for product types excluded from reporting requirements, such as the Washington reporting law's exemptions for plastic shipping pallets manufactured before 2012, food and beverages, agricultural chemicals, tobacco products, drugs, and motor vehicles.24

Businesses with products falling under such exemptions should assess the strength of their exemption claims and work to present the best arguments possible to limit reporting duties.

Protect Sensitive Product Information with CBI Claims

Another important tool that companies can use to protect valuable data is a CBI claim. CBI protections have long been a feature of reporting regimes and afford businesses the opportunity to comply with reporting laws without publicly revealing trade secrets or other sensitive information.

At the federal level, EPA regulations govern the submission of CBI claims for reports under TSCA. Any CBI claim must be made concurrent with the submission of product data; any confidentiality claim not accompanying a data submission will not be recognized by EPA, and all information included in the submission may be made publicly available.25 CBI claims for TSCA data submissions must also be substantiated at the time of reporting, unless the submitted data falls within an exempt category.26 Information that does not require substantiation includes:

- Specific information describing the processes used in manufacture or processing of a chemical substance, mixture, or article;

- Marketing and sales information;

- Information identifying a supplier or customer;

- Details of the full composition of a mixture and the respective percentages of constituents;

- Specific information regarding the use, function, or application of a chemical substance or mixture in a process, mixture, or article; and

- Specific production or import volumes.27

Other substantiation exemptions are available for chemical substances that have not yet been offered for commercial distribution at the time of reporting.28 EPA regulations allow companies filing CBI claims to keep the substantiation information out of the public record without separate substantiation grounds.29

For non-exempt information, TSCA requires reporters to provide detailed responses to substantiation questions on the competitive nature of submitted data, the potential harm public release of data could cause, the duration of the intended confidentiality claim, and whether EPA or another federal agency has made a prior confidentiality determination related to the chemical in question.30 The response to these inquiries represents the core of the CBI claim. At a basic level, a business must explain to EPA how the release of this information would create immediate and substantial harm to its competitive status, and what steps it has taken to protect this information. Failure to answer all CBI substantiation questions will result in EPA's denial of the confidentiality claim.

EPA will review all CBI claims for TSCA reporting within 90 days. Importantly, determinations on CBI claims are public records themselves, so companies may want to think about the strength of their confidentiality claims before potentially tipping off competitors to valuable data submissions.

State CBI-claim procedures are less detailed than the federal TSCA guidelines. For example, Ecology allows requests to certify submitted records as confidential. Such requests are reviewed by Ecology to determine whether confidentiality would be detrimental to the public interest and whether confidentiality would otherwise be in accord with departmental policy.31 State regulators may also refer to federal regulations to set expectations for state CBI submissions.

Overall, CBI claims offer businesses affected by PFAS reporting laws an avenue to shield sensitive information that could disadvantage their competitive position or expose them to liability. Crafting confidentiality claims requires forethought and coordination, as requests and responses to CBI claims could pose issues themselves. A request for or a denial of a CBI claim may be discoverable as a public record and could divulge the information that company originally sought to have protected. Carefully examining relevant confidentiality laws and regulations before submitting a CBI claim is critical to successfully safeguarding sensitive information.

Consider Filing Public Records Requests to Learn More About Reporting Demands

Accessing publicly available reporting data can help businesses prepare for their own reporting efforts and understand the position of competitors. If a peer company has already either complied with a state agency's reporting request or has submitted historic PFAS chemical data, filing a public records request could unearth valuable information. Additionally, a public records request for a reporting demand itself as opposed to a reporting submission could also provide much needed information for a company expecting to receive its own administrative order by marking the road ahead.

Conclusion

Compliance with the various state and federal PFAS reporting regulations while also protecting sensitive information will require diligent planning. Developing internal and external resources to enact the recommendations discussed above—from appealing reporting demands to filing and substantiating CBI claims—is a pressing business need for companies affected by PFAS reporting laws.

Footnotes

1. Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. 70,516, 70,516 (Oct. 11, 2023) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 705).

2. Victor Y. Xu, Minnesota and Washington Blitz PFAS in Products; Maine Backpedals, Marten Law (June 15, 2023), https://www.martenlaw.com/news...; James B. Pollack, PFAS in Consumer Products are Targeted by State Regulators and Class Action Plaintiffs, Marten Law (Jan. 4, 2023), https://www.martenlaw.com/news....

3. James B. Pollack, Victor Y. Xu, & Emma L. Lautanen, New EPA PFAS Reporting Rule Covers Thousands of Products, Marten Law (Oct. 30, 2023), https://www.martenlaw.com/news....

4. Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,516.

5. 40 C.F.R. § 704.3; Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,557 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.20).

6. 15 U.S.C. § 2613.

7. RCW 70A.350.020.

8. RCW 70A.350.040.

9. RCW 70A.350.030; RCW 70A.350.050.

10. RCW 70A.350.030 (4); RCW 70A.350.030 (2)(a).

11. RCW 70A.350.030 (4); RCW 70A.430.060.

12. RCW 70A.350.070 (1).

13. WAC 173-337-110 (4).

14.Id.

15. Washington also has mandatory PFAS reporting in place for children's products containing PFOA and PFOS. WAC 173-334-010 et seq.

16. 38 MRSA §1614 (2)(A)

17.An Act to Support Manufacturers Whose Products Contain Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, Public Law 2023, c. 138 (2023).

18. Minn. Sess. Law-2023, Chp. 60. H.F. No. 2310 Subd. 2.

19. Minn. Sess. Law-2023, Chp. 60. H.F. No. 2310 Subd. 2. (d).

20. WAC 371-08-335 (3).

21. WAC 371-08-340, WAC 371-08-345.

22. 38 MRSA §1614 (3).

23. 15 U.S.C. § 2602(2)

24. RCW 70A.350.030 (5)(a).

25. 40 C.F.R. § 703.5.

26. 40 C.F.R. § 703.5 (b)(1).

27. 40 C.F.R. § 703.5 (b)(5)(i).

28. 40 C.F.R. § 703.5 (b)(5)(ii).

29. 40 C.F.R. § 703.5 (b)(1).

30. 40 C.F.R. § 703.5 (b)(3).

31. RCW 43.21A.160.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.