1. Private Clients

1.1. Entrepreneurs' relief – practical issues (Cont.)

ICAEW Tax Faculty issued a Taxguide in February 2012 covering a number of technical queries on the operation of Entrepreneurs' Relief (ER) that were put to HMRC through the Capital Gains Tax Liaison Group. This note reflects the queries in sections E (settlement assets), F (partnerships), G (qualifying company definition) and H (rate changes and deferred gains) together with HMRC's responses.

It is understood that the HMRC guidance on ER (which can be found at CG63950 et seq of the HMRC Capital Gains Manual) will be extended to cover most, if not all, of the issues raised in this guidance.

All references are to TCGA 1992 unless otherwise noted.

SECTION E – DISPOSAL OF SETTLEMENT ASSETS

EXAMPLE E1 – Trustees and qualifying corporate bonds (QCBs)

The treatment of trustees appears to be less favourable than that of beneficiaries where QCBs are in point. Section 169R does not appear to apply to trustees, and the trustees cannot use s 169Q to elect to disapply s 127 where the security received is a QCB because s 116(5) says that ss 127–130 shall not apply.

The transitional rules in para 7, Sch 3, FA 2008 apply to individuals and not to trustees.

HMRC response to Example E1

The election under s 169Q to disapply the normal no disposal treatment in s 127 for share reorganisations (etc) is available to trustees and individuals. That section is of no relevance to QCBs acquired by either individuals or trustees. The reason is that the normal rules for QCBs already prevent the s 127 treatment from applying where shares (etc) are swapped for a QCB.

We have not yet had an opportunity to look back at the reasons behind the drafting of s 169R and the transitional rules in para 7, Sch 3, FA 2008. ER is essentially a relief for individuals, and additional complexity generated by the differences between the qualifying conditions for disposals by individuals and trustees may have been factors.

We would be interested to know if the scope of s 169R has caused any problems in practice.

EXAMPLE E2 – Making the claim for ER

In CG 63970 of the Capital Gains Manual it is stated that a claim for ER should be made in the self assessment tax return. However, a claim by trustees must be signed by the qualifying beneficiary who would not, normally, be a party to the trust tax return.

Could you clarify what the preferred means of making such a claim should be? How is a claim made when the trust tax return is filed electronically?

HMRC response to Example E2

Section 169M(2)(a) requires that a claim for ER in respect of a disposal of trust business assets must be made jointly by the trustees and the qualifying beneficiary. As the statute does not provide for any specific method of making the claim there is no preferred means apart from compliance with the legislation. Ideally a joint claim should accompany the trustees' tax return for the year in question. If the return is filed online the claim will have to be sent to the trustees' tax office separately, with a suitable covering note. Help Sheet 275 Entrepreneurs' Relief contains a template claim which will accommodate claims made jointly by the trustees and the qualifying beneficiary.

EXAMPLE E3 – Death of a relevant beneficiary

Can ER be claimed when a post-2006 trust ends on the death of the life tenant?

For example: the qualifying beneficiary mentioned in s 169J has died, triggering the end of the trust (with the property going to the remainderman). Therefore, there is a deemed disposal (s 71(1), TCGA 1992) which is not exempt (s 73(2A), TCGA 1992).

If the beneficiary met the qualifying conditions up to the date of death then ER should apply where there is qualifying business property with the trust. However, a valid claim needs to be signed by both the trustees and the beneficiary (or in this case the personal representatives for the beneficiary). Will such a claim be accepted by HMRC?

HMRC response to Example E3

We can see no reason why ER should not be available in the circumstances described. A joint claim by the trustees and personal representatives of the deceased beneficiary should not cause a problem.

SECTION F – PARTNERSHIPS

EXAMPLE F1 – Fractional partnership shares

Does HMRC accept that the disposal of a fractional profit share (whether it is a drop from 3% to 2% or from 60% to 59%) will always qualify as a qualifying business asset under s 169I (2)(a), TCGA 1992?

HMRC response to Example F1

There is no de minimis limit for the reduction in partnership share that constitutes the disposal of part of a business.

SECTION G – THE QUALIFYING COMPANY DEFINITION

EXAMPLE G1 – Trading status of a company

Can a taxpayer apply for a ruling on the trading status of a company?

HMRC response to Example G1

CG64100 states that "a company can seek from HMRC an opinion under the terms of the Non-Statutory Business Clearance service as to its trading status for the purpose of a shareholders ER claim."

Further query

To make a valid claim for ER on the disposal of shares it is necessary to know whether the company was a trading company or holding company of a trading group during the relevant period. This is not always clear. CG64100 advises the taxpayer to seek assurance from the company itself and if the company does not know, the company should itself ask for an opinion from HMRC under the Non-Statutory Business Clearance Service.

The Non-Statutory Business Clearance Guidance at NBCG 2200, however, indicates that the business should only use the clearance service when there is an issue of commercial significance for the business itself. The trading status is only of consequence to the shareholder not to the company, unless the company is also relying on the same definition of "trading" as used for the substantial shareholdings(SSE) for the company (para 10, Sch 7AC, TCGA 1992).

The two sets of guidance appear contradictory, please could you clarify?

HMRC further response

NBCG 2200 imagines there is "... uncertainty about the tax consequences of a transaction affecting the business" and while it also says that "This is not expected to include applications which clearly fall within the area of personal taxation of individuals ...", in the infrequent event of there being real doubt about a company's trading status a non-statutory business clearance application may be appropriate to ensure consistency of view for the purpose of ER for the individual shareholder and SSE for the company.

SECTION H – THE RATE CHANGES AND DEFERRED GAINS

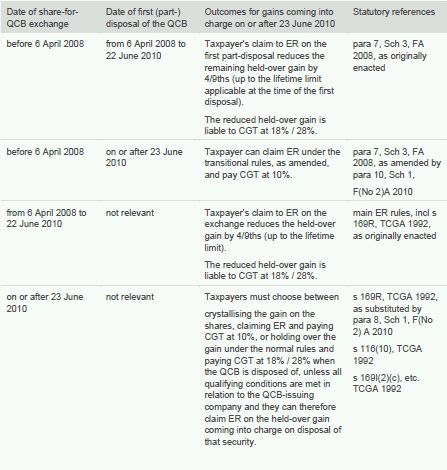

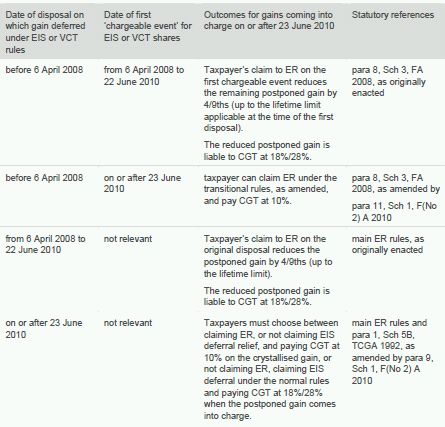

HMRC has provided the following tables summarising the CGT position where a gain comes into charge after 22 June 2010 where there has been a share-for-QCB exchange (Table 1) or where a gain has been deferred under the EIS or VCT rules (Table 2).

Table 1 – ER and QCBs: HMRC table summarising the various potential outcomes.

Table 2 – ER and EIS deferral relief: HMRC table summarising the various potential outcomes:

EXAMPLE H1 – What is the treatment of QCBs received between 6 April 2008 and 22 June 2010 in respect of which the held-over gain has, as a result of a claim for ER, been reduced by 4/9ths?

Clearly, as set out in the above tables, if there is a disposal of the QCB after 23 June 2010, and the holder does not qualify for ER in relation to the issuing company at that time, CGT will be payable on the held-over gain at 18% or 28%, giving an effective rate of 10% or 15.56%. But what if, at the date of disposal of the QCB, the holder does qualify for relief again?

We recently received a query as to whether an effective rate of 5.56% (5/9 at 10%) would apply if a claim for ER is submitted in respect of the (already reduced) held-over gain when it comes into charge. If the noteholder meets the employment and shareholding conditions at the time of the disposal of the QCB, the disposal will constitute a material disposal within s 169I(c), TCGA 1992. Relief under s 169N(5)(a) will relate to relevant gains "computed in accordance with the provisions of this Act fixing the amount chargeable gains."

On this basis, we cannot see why the relief cannot be claimed twice, first on the share-for-QCB exchange and, again, on the disposal of the QCBs.

Please can you either confirm that a double claim is possible or provide a technical analysis of why such a claim would fail?

HMRC response to Example H1

We can see there is a case for concluding that an effective 5.56% rate of CGT is possible in the circumstances you outline. But the case is not beyond doubt. On the other hand, a 5.56% rate is not plainly impossible. If an actual case arises we would need to arrive at a considered view taking into account any legal advice on the issues.

The issues may centre around whether the "frozen gain" that s 116(10)(b) deems to accrue on a disposal of the QCB in question can be a "relevant gain" on which s 169N gives relief – the 10% rate of CGT. Section 169N(5) defines these gains as, in this context, the gains accruing on the disposal of the QCB. A simple reading could suggest that a 'frozen' gain on a QCB would be a "relevant gain". But the words in s 169N(5) need to read as they are written, that is, the gains accruing on the disposal. Two contextual points in ER (Ch 3, Pt 5, TCGA 1992) may have a bearing: first, the meaning of "relevant gains" in para (b) of s 169N(5) – gains accruing on the disposal of any relevant business assets comprised in the qualifying business disposal; second, the election in new s 169R to allow ER, effectively by preventing the gain in question being "frozen" under s 116(10).

It may be that, after taking into account these and all other relevant matters, the better view is that the ER rules do not allow a "double claim" in the way you suggest.

EXAMPLE H2 – The effect of a change in the lifetime allowance and deferred gains

Given the way the legislation worked prior to 23 June 2010, where an ER claim was made and the gain was deferred (either as a result of the QCB legislation at s169R or of an EIS deferral claim), it was the gain as reduced by ER that was deferred. It appears therefore that if the gains were in excess of the unused lifetime allowance at the time (eg a gain of £2m realised on 22 June 2008 when the lifetime allowance was £1m) but not the allowance at the date it comes into charge (eg the disposal of the new asset takes place on 18 July 2010.

when the lifetime allowance is £5m) it cannot benefit from the allowance increase. Is this HMRC's understanding?

The issue cannot arise for transactions after 22 June 2010 as the new regime does not allow deferral of the tax liability and EIS relief.

HMRC response to Example H2

We agree that in any case where ER applies under the original rules then the lifetime limit at the time of the first claim will have fixed the amount of the relief on any deferred gains, even if a bigger lifetime limit is in force at the time the deferral ends.

EXAMPLE H3 – The tax rate where qualifying gains are deferred

This query relates to cases where individuals are temporarily non-resident but subject to charge under s 10A, TCGA 1992 in the year they return to the UK, or where they are liable to CGT on the remittance basis. Previously, if an individual made a claim for ER, this reduced the amount of the chargeable gain by 4/9ths (the deadline for the claim was based on the disposal date rather than the date it comes into charge, so you could be claiming before it was charged to tax). When the gain came into charge (in the year of return or the year of remittance), the reduced gain was charged at the prevailing rate.

The relief no longer works as a fractional reduction and s 169N(3) says "The rate of capital gains tax in respect of that gain is 10% ...". This seems to indicate that the rate of tax is fixed at the point of disposal, irrespective of the date of the tax charge. So someone could make a gain now, but when it is taxed in one or 20 years' time, it would be taxed at 10%, as it is the same gain. Is this correct?

HMRC response to Example H3

We see the point being made, but do not believe that this is an issue. If at some future time the Government wishes to alter the 10% ER rate, either upwards or downwards, a policy decision will be needed as to whether to retain the 10% rate on gains deferred from disposals in earlier years.

2. PAYE and Employment matters

2.1. Definition of mobile phone (treatment of smartphones)

HMRC has announced a change of view on the interpretation of s319(4) ITEPA 2003, which deals with the definition of the term 'telephone apparatus', which is used in the definition of 'mobile phone' in s319(2). S319 ITEPA provides an exemption from income tax in respect of the provision of one mobile phone per employee without any transfer of ownership.

From around late 2007 onwards, HMRC considered that smartphones were to be treated in the same way as personal digital assistants (PDAs). This view was based on the understanding that smartphones were not devices designed or adapted for the primary purpose of transmitting and receiving spoken messages and used in connection with a public electronic communications service.

HMRC now considers that its application of the legislation to smartphones is incorrect and accepts that smartphones satisfy the conditions to qualify as 'mobile phones'. Developments in PDAs following the penetration of smartphones into consumer markets from late 2007 onwards mean that many modern consumer PDAs are now also likely to be smartphones. But this will not apply to devices that are solely PDAs.

Where a smartphone is provided to an employee in 2011-12, it is to be treated in the same way as any other mobile phone. A benefit will only be included on form P11D for any mobile phones/smartphones that are either over and above the first one provided to the employee or which are provided to a member of the employee's family or household rather than to the employee personally.

Where an employer provided a smartphone for 2010-11 and years back to 2007-08 and the three bulleted conditions listed below are satisfied, a claim can be made for repayment of the Class 1A NIC liabilities in relation to the benefits of the smartphones. The claim requires various details and HMRC will use this same information to identify any repayments of income tax due to employees.

This change of view will be relevant to those employers that have:

- provided just one smartphone to their employees without transfer of ownership;

- treated that smartphone as a device that falls outside the meaning of 'mobile phone' for the purposes of the exemption in s319 ITEPA 2003;

- included entries in form P11D and form P11D(b) for the benefit of the availability and use of that smartphone and for the corresponding Class 1A NIC liability (or included the benefit in a PAYE Settlement Agreement).

HMRC expect that the instances where all three conditions are satisfied will be rare as, in its view, in many cases employers and tax advisers may have taken the view that the smartphone used was covered by the mobile phones exemption or employers are likely to have provided such devices in circumstances covered by the separate exemption in s316 ITEPA 2003 for supplies and services used in employment duties. This exemption applies to certain categories of asset where the sole purpose for providing it is to enable the employee to perform the duties of the job, provided that private use is not significant.

www.hmrc.gov.uk/briefs/income-tax/brief0212.htm

2.2. Conditional share scheme and Manthorpe Building Products Ltd

This was a case where an attempt was made to remunerate directors in a manner that would enable the Appellant to obtain a deduction for corporation tax purposes for the cost of the effective remuneration, whilst simultaneously endeavouring to avoid PAYE and National Insurance contribution ("NIC") liabilities by procuring that the payments were made as dividends paid by a specially formed company, thus attracting tax at the lower relevant rate for dividends, and no liability for either employee or employer NIC contributions. It was similar in structure to the circumstances of the PA Holdings case (see Tax Update 5 December 2011).

Under the scheme, Manthorpe Building Products Ltd (MBPL) formed a UK resident unlimited company called Manthorpe Investment Services ("Manthorpe Investments"). MBPL itself always held the voting shares in Manthorpe Investments. It made a capital contribution of £1,050,000 to Manthorpe Investments and then subscribed 10,000 1p shares which carried the right to a priority dividend of anything between nil and £1,000,000, payable on or shortly after 30 September 2004. MBPL's bonus plan envisaged that if MBPL's sales for August and September 2004 reached or exceeded £1,000,000 (a 4.4% increase on the sales for the comparable period of 2003) Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol would respectively receive £800,000 and £200,000 as their entitlement under the bonus plan. Were the targets not achieved they would receive the lower, so called "guaranteed", amount of £875,000, rather than £1,000,000, between them. The 1p shares were then transferred to Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol in the ratio 80/20. The intention of this transfer of the 1p shares to Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol was that the bonus plan would be effected via the share rights of Manthorpe Investments.

HMRC had conceded that the cost of the payment made by MBPL technically to Manthorpe Investments, but indirectly to fund the dividend payments, was deductible for corporation tax purposes.

The case on the PAYE and NIC liabilities was decided on the same basis as the PA Holdings case, but the First Tier Tribunal considered three alternative basis of assessment put forward by HMRC. These were:

- The contention that the bonus plan conferred a general right to bonuses, in fact satisfied by the so-called dividend mechanics, but nevertheless a general right which could have been enforced by the two directors by the simple receipt of cash payments, and that this occasioned a PAYE liability when the right was granted, and not one vacated on any analysis by section 20(2) ICTA;

- The contention that although the wording that accompanied the payment of £1,050,000 made by the Appellant to Manthorpe Investments suggested that Manthorpe Investments could do as it wished with the money contributed, in fact the terms of MBPL's Board Minute indicated that Manthorpe Investments would be told to deal with the monies in such a manner that enabled it to pay the £1,000,000 to Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol, should the targets be met, as was virtually bound to be the case. Accordingly Manthorpe Investments received no profit when the capital contribution was ostensibly made to it. In reality it was a paying agent, which was handed money by its controlling shareholder that it would have to apply in discharging a pre-existing commitment. On this approach, there was neither a profit, nor were the dividends in reality dividends;

- The contention that there is the second approach that the Court of Appeal dealt with in the P.A. Holdings case, namely that on applying the Ramsay principles, now generally taken to require the notion of judging the facts realistically and interpreting the law purposively, the PAYE liabilities should have been confirmed by reference to that analysis, quite apart from the earlier elements of the Court of Appeal judgment, related to the proper application of the charge to tax of the payment as remuneration altogether precluding taxation as a dividend, such that section 20(2) was never engaged.

On the first bullet point above, the Tribunal disagreed with the HMRC view as the right was only in relation to a right that the company would procure the dividend or reduction of capital payment envisaged, that would (had ICTA s20(2) applied) have been treated as a dividend, and would not have attracted tax on a different basis.

On the second bullet point, the Tribunal commented:

We accordingly consider that when we interpret the facts realistically, as we are required to do, the reality was that as regards at least £1,000,000 paid to Manthorpe Investments, Manthorpe Investments was just a paying agent to discharge a commitment that its controlling shareholder had undertaken. Having regard to the liability that Manthorpe Investments had got to discharge on behalf of its controlling shareholder, we conclude that it had a profit, only to the extent of any excess over the matching liability that in reality it had got to discharge. Accordingly the £1,000,000 was not a capital contribution; there was no profit to that extent, and the so-called dividends were not in fact dividends paid out of profits, but the discharge of the liability on the part of the contributor that in reality Manthorpe Investments had got to meet.

The Tribunal also determined the performance targets were genuine performance targets to only a very limited extent.

On the third bullet above, the Tribunal concluded they could well have applied the Ramsay principle to deem the payments to have been subject to PAYE and NIC.

They made a further observation on the liability for PAYE resulting from the decision, concluding that this was a liability of the company, not the individuals. They commented:

The very simple point that we make is that if Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol's Income Tax affairs for the relevant period are still open so that the dismissal of this appeal means that any Income Tax charged on the dividend analysis will be refunded by HMRC, it will then follow that it is the Appellant [MBPL}] and not Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol that will be liable for the PAYE tax and the employer and employee NIC liabilities. Those are presently assessed by reference to the amount that should have been deducted on paying bonuses, so that very roughly the amounts are £400,000 in PAYE tax (at the 40% rate of £1 million) and say £100,000 in PAYE contributions. Had those amounts been deducted from the initial payments, Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol would have had in hand only the aggregate net sums of approximately £500,000. As it is, they will have £1 million (indeed the full £1,000,000, if the tax on the dividend is refunded, and therefore actually more than they would have had in hand, had the scheme succeeded), and whilst the Appellant will have to pay the PAYE tax and the NIC contributions, those sums will at least be calculated by reference to the £1 million and not to the very much higher sum that would have had to be paid in the first place if Mr. and Mrs. Pochciol were to be left with the £1 million that they now have.

www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKFTT/TC/2012/TC01778.html

3. Business tax

3.1. Taxpayer seeking to apply the transfer of assets abroad legislation

The Upper Tribunal has considered the ability of a taxpayer to invoke the transfer of assets abroad provisions in order to get double tax relief not otherwise available. By contrast HMRC sought to maintain that the motive exemption applied so that the anti-avoidance did not apply! In summary the Upper Tribunal rejected the taxpayer's contention that the anti-avoidance was invoked (which would have given him access to double tax relief), and concluded there was no tax avoidance relating to the transfers or associated operations.

As noted in Tax Update 15 August 2011, due to difference in treatment of income accruing to an individual from a US LLC when considering US tax and UK tax, the individual (Mr Anson), ended up paying tax at 67% in total, made up of 45% US tax and 22% UK tax. This is because on income of 100, he was liable to US tax of 45, while the net amount (55) was subject to UK tax at the rate of 40% resulting in a further 22 of tax. The conclusion of the Upper Tribunal was that from a UK perspective the income of the US LLC was corporate in form, so that Mr Anson as an individual did not have any entitlement to credit for the underlying tax suffered within the US LLC. However the amount net of US tax that Mr Anson received in the UK would be subject to UK income tax.

Counsel for Mr Anson contended that if the income of the LLC had been fully subject to UK tax, using the example above, there would have been UK tax of 40 instead of 22. He also contended that HMRC did not have sufficient information to conclude that the taxpayer's motive was not one of tax avoidance, so that the transfer of assets abroad provisions applied, notwithstanding the fact that Mr Anson had suffered an effective rate of tax of 67% on the profits. Counsel was careful not to say that Mr Anson did in fact have any tax avoidance motive. It is not clear from the case summaries how the motive exemption was declared as effective through the original returns, though HMRC's transfer of assets abroad expert, Mr Turner, declared himself satisfied that there was no tax avoidance motive and the arrangements were genuinely commercial.

The Upper Tribunal concluded that the fact that Mr Anson might have expected to pay US tax of 45 and UK tax of nothing (the US tax amount exceeding the amount that would have been payable if the same income had been subject to UK tax) did not provide any material evidence to show that Mr Anson was seeking to avoid paying UK tax. Although there could be some refinements to the reasoning of the First Tier Tribunal and the evidence of Mr Turner, the Upper Tribunal concluded the First Tier Tribunal reached the correct conclusion.

Of particular interest with regard to how the motive defence for the transfer of assets abroad legislation is invoked, is the Upper Tribunal's comments at para 18 of the judgement. As indicated in HMRC manuals at INTM600040, HMRC expect the taxpayer to give the following information:

- details of the amount considered to be exempt from charge (S&W practice is that if it is considered the cost of quantifying a non-taxable amount outweighs any benefit from this information, disclosure of this opinion and variation from HMRC guidance should be given);

- particulars of transfers and associated operations that would result in the charge absent the exemption;

- an explanation of the basis for considering the motive exemption conditions to be met.

It is interesting to speculate whether the comments in the Anson case imply that such extensive disclosure by the taxpayer is necessary initially, as it indicates the structure of the legislation indicates it would be HMRC who would invoke the legislation and the taxpayer would resist it. The comment in the case at para 18 was:

"I confess to a certain amount of reluctance to start this case on the apparent shared premise of the parties, which is that section 739 is capable of having anything to do with it at all. It seems to me to be extremely odd that a section which in terms is expressed to have anti-avoidance as its purpose can actually be turned to account by the taxpayer invoking it. The whole structure of section 739 and the following sections clearly anticipates that it will be the Revenue invoking sections 739 and the taxpayer resisting it. That is apparent from the terminology of section 741 and the assumptions obviously underlying it. It is also the sort of thing that Parliament is likely to have had in mind in enacting section 745, which I have not set out in this decision but which gives the Revenue power to seek information. I am sure that Parliament had in mind the need of the Revenue to get information in order to see whether a case could be made under section 739, not to get information in order to rebut the taxpayer's claim to apply it, and in particular to establish that there was no intention to seek to avoid tax. I am surprised that it is no part of the Revenue's case to advance arguments which would prevent its invocation at all."

www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKUT/TCC/2012/59.html

3.2. Employer asset backed pension contributions

The Government announced on 29 November 2011 that legislation, effective from the announcement, will be included under Finance Bill 2012 to ensure that the amount of tax relief given to employers using asset backed contributions (ABC) arrangements reflects accurately the total amount of payments the employer makes to the pension scheme directly or through a special purpose vehicle (SPV) (for example a partnership).

Further Finance Bill 2012 legislation was published on 22 February 2012 to take effect from the same date. In line with the policy objective, this further legislation ensures that up-front relief will not be given unless the whole total of all asset backed payments to the pension scheme are to be of fixed amounts at the outset.

Legislation will be introduced in Finance Bill 2012 to make changes to FA 2004 as follows:

- New arrangements - where the contribution is paid on or after 22 February 2012, then the February legislation will apply. If the contribution under an ABC arrangement is paid on or after 22 February 2012, tax relief in the form of an upfront deduction will be given for the contribution under the ABC arrangement only where the new qualifying conditions and SFA (structured finance arrangement) rules are both met (this means the ABC arrangement is an acceptable SFA). Relief will also be available under the SFA rules for the element of subsequent income payments that is accounted for as a finance charge in relation to the financial liability recorded in the accounts of the employer, or if used, the SPV.

- November-February arrangements - where an ABC arrangement is set up with the employer contribution paid on or after 29 November 2011 but before 22 February 2012, the November legislation applies to determine whether up-front relief is available. The transitional provisions in the February legislation will apply to payments that arise on or after 22 February 2012 under such arrangements and also in circumstances where such an arrangement comes to an end on or after 22 February 2012. Where these apply if value of any up-front contribution relief and the relief for any subsequent payments exceeds the value received by the pension fund, there will be a clawback.

- Pre-November 2011 arrangements - where an ABC arrangement is set up with the employer contribution paid before 29 November 2011, the November legislation applies if the arrangement continues at 29 November 2011. Where the November transitional rules do not apply, the transitional provisions in the February legislation will apply to payments that arise on or after 22 February 2012 and where such an arrangement comes to an end on or after 22 February 2012. There may be a clawback if excess relief has been obtained.

The main difference between the two sets of provisions is that the February legislation introduces new qualifying conditions that must be met in respect of arrangements in order to qualify for up-front relief. These conditions deliver the policy objective and the intended effects of the November legislation. The February provisions ensure that up-front relief will only be given when an ABC arrangement is an 'acceptable SFA'. An arrangement is an acceptable SFA if it meets both these qualifying conditions and the SFA rules.

www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/asset-backed_pension_220212.pdf

www.hmrc.gov.uk/budget-updates/wms.pdf

www.hmrc.gov.uk/budget-updates/tiin-draft.pdf

3.3. Bank Levy double tax statutory instruments

Regulations have been issued permitting double tax relief for the bank levy in respect of German (SI 2012/459 and SI2012/432 setting out a convention and protocol specifically referring to the bank levy and the equivalent German levy) and French (SI 2012/458) taxes which are equivalent to the bank levy. The regulations (which come into force on 14 March 2012) have effect for accounting periods commencing on or after 1 January 2011, except in relation to the order referring to German taxes for which certain credit relief is given (this latter part of the regulations having effect for accounting periods beginning on or after 14 March 2012).

www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/459/pdfs/uksi_20120459_en.pdf

www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/432/pdfs/uksi_20120432_en.pdf

www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/458/pdfs/uksi_20120458_en.pdf

3.4. Landfill Tax in Scotland – written ministerial statement

Economic Secretary to the Treasury (Chloe Smith) announced on 21 February 2012 that the Government will introduce legislation in Finance Bill 2012 to correct a flaw in landfill tax legislation, which means that landfill sites in Scotland have unintentionally been outside the scope of landfill tax.

The definition of a landfill site in landfill tax legislation refers to environmental legislation. Changes were made to this environmental legislation which meant that in 1999 sites moved from a framework of licences to a system of permits. Landfill tax legislation was duly amended and these amendments were brought into effect in England and Wales on 21 March 2000 and Northern Ireland on 17 January 2003. However, the Scottish Government did not introduce the necessary commencement order, thereby unintentionally taking each Scottish landfill site outside the scope of landfill tax from the date each new permit took effect.

The legislation will have full retrospective effect from 21 March 2000 to bring Scottish legislation into line with that in the rest of the UK.

Operative date

The legislation will have full effect from 21 March 2000.

Current law

Section 66 of Finance Act 1996 provides the interpretation of the term 'landfill sites' for landfill tax purposes. Section 66(ba) of the Finance Act 1996 was inserted by section 6(1) and paragraph 19 of Schedule 2 to the PPCA 1999. Provision was made for a commencement order to bring the inserted provision into force.

The Pollution Prevention and Control Act 1999 (Commencement No 1) (England and Wales) Order 2000 (SI 2000/800) brought the provisions into force in England and Wales from 21 March 2000 (and separate legislation applies to sites in Northern Ireland). However, the Scottish commencement order, the Pollution Prevention & Control Act 1999 (Commencement No. 2) (Scotland) Order 2000 (SSI 2000/322) did not bring the relevant provision into force in Scotland.

Proposed revisions

Legislation will be introduced in Finance Bill 2012 to deem section 66(ba) of the Finance Act 1996 to have been in force in Scotland since 21 March 2000.

3.5. Stamp Taxes Bulletin

The first Stamp Taxes bulletin for 2012 has been issued. Amongst the areas covered is a reminder that Finance Bill 2012 will contain a new regulation-making power to facilitate two changes to the DOTAS regime for SDLT:

- removal of some "grandfathering" rules for certain schemes;

- removal of property valuation thresholds for disclosure.

The first of these will require certain grandfathered schemes to be disclosed one additional time so that new users of the scheme must be identified to HMRC.

The operative date for the regulation-making power will be the date of Royal Assent, but the measure will only have effect once new regulations come into force at a later date.

www.hmrc.gov.uk/so/bulletin01-2012.pdf

4. VAT

4.1. HMRC manual updates

The VAT Business/Non Business manual has been updated to include (amongst other things) reference to the registration scheme for racehorse owners.

www.hmrc.gov.uk/manuals/vbnbmanual/updates/vbnbupdate200212.htm

The VAT Finance manual has been amended to reflect new place of supply rules; and the effect of various cases added, including Kingfisher Plc (2000 STC 992), and ECJ judgments in AXA (C-175/09), Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB Momosgrupp (Case C-540/09) and Velvet & Steel Immobilien und Handels GmbH (C-455/05).

www.hmrc.gov.uk/manuals/vatfinmanual/updates/vatfinupdate210209.htm

The VAT Input Tax manual has been updated to include amongst other things an update to the page VIT4100 on holding companies. The new text is as follows:

In simple terms a holding company is a company that holds shares in one or more subsidiary companies. Holding companies have a range of structures and purposes. Some have minimal activities. They hold shares in subsidiaries and receive dividends but play no part in the management of the investment. Others are actively concerned with the supervision and management of the subsidiaries.

The status of holding companies has been examined by the courts on many occasions. You should think about whether the holding company is holding and managing its investments in companies for the purpose of receiving dividends in a fashion that is no different from that of a private investor whose activities do not amount to a business, as in Polysar.

Alternatively, it may be acquiring those shares primarily to provide management services and therefore be carrying on a business, as in Cibo. There is ongoing litigation about whether input tax can be claimed on certain acquisition costs. See BAA at VIT64050.

The issue in all these cases is whether and to what extent a holding company can be properly said to be carrying on an economic activity (referred to as a business in UK law). In considering the question the courts have looked at both parts of the definition of economic activity. In other words, the courts have thought about whether the holding company was a person supplying services or was exploiting intangible property.

See the definitions of taxable person and economic activity in Article 9 of the Principal VAT Directive at VIT11000. See also the definition of input tax in section 24 of VAT Act 1994 at VIT11500.

www.hmrc.gov.uk/manuals/vitmanual/updates/vitupdate210212.htm

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.