- within Tax topic(s)

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy and Business & Consumer Services industries

- within Tax, Environment and Privacy topic(s)

Speed read

Despite previously describing the Ramsay principle as having 'reached a state of well-settled maturity', in Royal Bank of Canada the Supreme Court was divided on when and how the principle applies. One might infer that Ramsay is now restricted to tax avoidance cases, or limited to domestic legislation; a more palatable inference is that Ramsay was applicable yet had no effect, either because the treaty did not support a broader purposive interpretation, or because a realistic view of the facts did not require a departure from the contractual position. In either case, the decision leaves the state of the law unclear.

Lord Nicholls once wrote that the principle in W T Ramsay Ltd v IRC [1982] AC 300 (Ramsay) 'rescued tax law from being "some island of literal interpretation" and brought it within generally applicable principles' of statutory interpretation (Barclays Mercantile Business Finance Ltd v Mawson [2004] UKHL 51) (Barclays). Despite Ramsay now being more than 40 years old, the Supreme Court, in Royal Bank of Canada v HMRC [2025] UKSC 2 (RBC) disagreed about when and how Ramsay applies.

The Ramsay principle

Ramsay set out two principles. First, while the imposition of tax must be on the basis of 'clear words', this does not confine the courts to a literal interpretation; the context and purpose of the relevant legislation should be taken into account. Second, the court's role is to ascertain the nature of the transaction in question, and if that nature emerges from a series or combination of transactions, the court may look at that series or combination. These principles are summed up in two oft-quoted dicta:

'The essence ... was to give the statutory provision a purposive construction in order to determine the nature of the transaction to which is was intended to apply and then decide whether the actual transaction (which might involve considering the overall effect of a number of elements intended to operate together) answered to the statutory description' (Barclays, at [32]).

Or, put more succinctly:

'The ultimate question is whether the relevant statutory provisions, construed purposively, were intended to apply to the transaction, viewed realistically' (Collector of Stamp Revenue v Arrowtown Assets Ltd [2003] HKCFA 46).

Although this might suggest a two-step process, the way the principles are applied by the courts in practice – and the language used when doing so – tends to become rather more amorphous.

Nonetheless, in Rossendale Borough Council v Hurstwood Properties (A) Ltd and others [2021] UKSC 16 (Rossendale), the Supreme Court described the Ramsay principle as having 'reached a state of wellsettled maturity'; it was 'clear beyond dispute' that it 'is an application of general principles of statutory interpretation'. That being so, why should it shy away from applying those same principles in Royal Bank of Canada v HMRC [2025] UKSC 2 (RBC)?

RBC: the facts

The Crown grants licences to companies to locate and extract oil on the UK continental shelf and bring it to market. The UK Government requires that those licenceholders are UK-incorporated companies.

One such licenceholder, Sulpetro (UK) Limited (Sulpetro UK), a UK tax-resident company wholly owned by the Canadian tax resident Sulpetro Limited (Sulpetro Canada). Sulpetro UK and Sulpetro Canada then entered into an agreement (the Illustrative Agreement) under which Sulpetro Canada provided the financing and expertise to carry out the exploration work, in exchange for all of Sulpetro UK's share of the oil. Although Sulpetro Canada provided the funds to pay the royalties owed to the UK Government, Sulpetro UK remained responsible for paying those royalties and for operating in accordance with the licence and UK law. This structure was not unusual but reflected a practice originating some decades earlier.

A few years later, Sulpetro Canada sold its rights under the Illustrative Agreement and its shares in Sulpetro UK to BP Petroleum Development Ltd (BP). As consideration for the novation of the Illustrative Agreement to BP, BP agreed to make overage payments to Sulpetro Canada (the Payments) once the market price of the oil exceeded US $20 per barrel (see Figure 1).

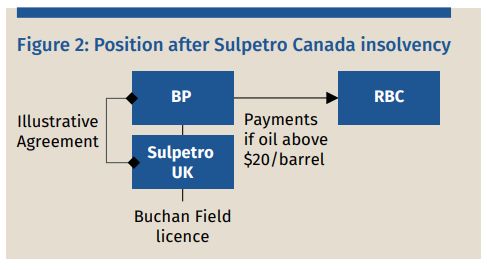

RBC was Sulpetro Canada's lender, so when Sulpetro Canada went into receivership, the right to receive the Payments was assigned to RBC by court order (see Figure 2). Although the Payments were charged to tax in RBC's hands in Canada, HMRC considered that they were taxable in the UK.

Article 6 of the UK-Canada double tax agreement provides for income from immovable property to be taxed in the State in which such property is situated. The definition of 'immovable property' for these purposes in Article 6(2) includes 'rights to variable or fixed payments as consideration for the working of, or the right to work, mineral deposits, sources and other natural resources'. The question before the court was therefore whether the Payments fell within the scope of Article 6.

It was 'clear beyond dispute' that the Ramsay principle 'is an application of general principles of statutory interpretation'. That being so, why should the Supreme Court shy away from applying those same principles in RBC?

RBC: the decision

Unusually for the Supreme Court, the decision in RBC was not unanimous. The majority, led by Lady Rose, agreed with the Court of Appeal in reading Article 6 narrowly, concluding that Sulpetro Canada did not have any right to work the Buchan Field: the UK Government granted the licence to Sulpetro UK, not Sulpetro Canada, and Sulpetro UK did not subcontract any part of the work to Sulpetro Canada. If Sulpetro Canada had no right to work the field, it could not have furnished BP with such a right, and so the Payments could not have been consideration for a right to work the field within Article 6. In addition, the term 'consideration for the right to work' was to be interpreted as capturing payments akin to a royalty payment where the rightsholder continued to have an interest in the property, not an outright disposal of all its rights as by Sulpetro Canada.

Lord Briggs, in 'lonely disagreement', considered that, on a purposive reading, Article 6 was engaged 'wherever there is an income stream being received as of right as the quid pro quo for the ability of someone other than the recipient to work UK situated mineral deposits or sources, or natural resources'. Turning to the facts, he considered that the combined effect of Sulpetro Canada's ownership of Sulpetro UK and its rights under the Illustrative Agreement was that Sulpetro Canada enjoyed the whole of the economic benefits and risks of working the relevant share of the Buchan field. Viewed realistically, that meant that Sulpetro Canada was working that share. The transfer of that ownership and those rights then, taken together, had the effect of enabling BP to continue that work, in exchange for which BP paid the Payments.

Lord Nicholls in Barclays did acknowledge there would always be some complexity in applying Ramsay 'because it is in the nature of questions of construction that there will be borderline cases about which people will have different views'. If RBC were such a case, there might be little left to say on the matter. However, it is anything but clear from the judgment that this is all there is to it.

What, if anything, does RBC tell us about the application of Ramsay?

Possibility 1: Ramsay is limited to tax avoidance cases.

Let's begin by addressing the elephant in the room. The majority decision only refers to Ramsay to dismiss it (at [90]):

'it is true that there has been a greater tendency of the courts to neutralise the effect of tax avoidance schemes by looking at the reality of a transaction to see whether it is a transaction that was intended to be caught by a particular taxing provision. ... The Ramsay principle ... explains when a court can to that extent focus on the reality of what is happening combined with a purposive interpretation of the taxing provision. No one here has suggested that the Ramsay principle has any application to the present facts and nothing in this judgment casts doubt on the efficacy of those principles where they apply' (emphasis added).

At first glance, it seems as though Lady Rose takes the view that Ramsay applies only in the context of tax avoidance – but, to mix metaphors, this elephant may be a red herring. While the majority of cases applying Ramsay do so in a tax avoidance context, the Supreme Court has applied the principle more broadly, including in R (on the application of Cobalt Data Centre 2 LLP and another) v HMRC [2024] UKSC 40, in which Lady Rose agreed with Lord Briggs and Lord Sales that the Ramsay principle enabled the court to find a construction that met the purpose of the statute without departing from the language used, or inserting language that was not there.

The Supreme Court may depart from its own previous decisions where it appears right to do so, but it would be unusual for it to do so without expressly acknowledging the departure.

If the majority decision is not restricting Ramsay to tax avoidance cases, what then does Lady Rose mean by the words 'where they apply'?

Possibility 2: Ramsay is limited to domestic legislation

The second possibility is that this is a jurisdictional issue. Both the majority and dissenting judgments note that Article 31 of the Vienna Convention requires interpretation of the treaty 'in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the lights of its object and purpose'. In his dissenting judgment, Lord Briggs draws a parallel between Article 31 and Ramsay: 'The purposive approach to the taxing provision is a perfectly general rule of statutory construction, and is no different in substance from that to be applied to the interpretation of a treaty'

The majority decision, however, does not comment on whether the Vienna Convention and the Ramsay principle intersect or overlap, nor does it indicate that they are competing methods of interpretation between which the court must choose. While it acknowledges that 'the language of an international treaty must not be interpreted by technical rules of English law', it is difficult to see that this statement and a passing reference to Ramsay could be intended as an authoritative statement that Ramsay does not apply to treaties.

And if Ramsay can apply to treaties, the extent to which the principle must be adapted to that context has significant implications for its effect.

Contained within the Ramsay principle is an implicit presumption that the tax legislation acts to tax the things which it sets out to tax: 'we cannot suppose that it was part of the purpose of the Act to provide an escape from the liabilities that it sought to impose' (Gilbert v IRC (1957) 248 F2d 399). It is this principle that Lord Briggs seems to follow when he says that, as well as avoiding double taxation, the purpose of Article 6 is 'to bring [income from immovable property] within the prior taxing right of one of the Contracting States'.

In fact, the majority decision also gestures towards the same assumption in finding that the reason Article 6 includes payments for 'rights to work' as well as 'working' is 'to ensure the recipient of the payments could not escape the tax charge'.

Applying Ramsay wholesale in this way ignores a fundamental difference between domestic legislation and double tax treaties

However, applying Ramsay wholesale in this way ignores a fundamental difference between domestic legislation and double tax treaties: whilst domestic legislation seeks to impose tax, and therefore it can be assumed that one of its purposes is not to provide a ready exclusion from that tax liability, a double tax treaty seeks to allocate taxing rights between two contracting states, and so there can be no presumption that one state or another should have those taxing rights. This could have justified a finding that, without a presumption against tax avoidance, applying Ramsay would not have the effect proposed by Lord Briggs, but unfortunately if the majority gave any significance to the distinction they did not say so.

If Ramsay is neither restricted to avoidance cases nor limited to domestic legislation, perhaps the suggestion that Ramsay does not apply is merely shorthand for a view that Ramsay had no effect in this case, either because Article 6 did not support a broader purposive interpretation, or because a realistic view of the facts did not require a departure from the legal position as established by the Illustrative Agreement.

Possibility 3: the 'realistic' view matches the contractual position

Much of the majority judgment focuses on the fact that the licence was granted to Sulpetro UK, not its parent, and that Sulpetro UK did not subcontract the operation of the field to Sulpetro Canada. Sulpetro Canada had neither a direct nor indirect right to work the field; it merely had a contractual 'right to require another person to work' it.

The majority agreed with the Court of Appeal that 'it is not possible to ignore the legal structure for the purpose of applying the provisions' of the treaty, stating that express language would be needed to permit the court to pierce the corporate veil. However, there is perhaps an elision here between ascribing the rights of a company to its shareholders and considering whether the rights as they appear on paper fairly represent the rights as they are in reality.

The rates avoidance scheme at issue in Rossendale involved the grant of leases to special purpose vehicles. Since there was no allegation that the leases were shams, Ramsay did not operate to disregard the leases (as it might have done with an unnecessary step inserted into a composite transaction purely to achieve a particular tax outcome), but rather required the court to consider whether the leases did in fact effect a change in the person entitled to possession within the meaning of the relevant statute. On the facts, they did not.

The same can be said of 'reverse' applications of Ramsay, where the principle is invoked in the taxpayer's favour. In Whittles v Uniholdings [1996] STC 914, the taxpayer had an exchange loss on a loan contract and an exchange gain on a forward contract, but the former was not allowable. The Court of Appeal rejected the taxpayer's argument that Ramsay should apply to treat the two as a single composite transaction, in part because the taxpayer genuinely wanted to borrow dollars instead of sterling because of the preferential interest rates, and the contractual position matched that intention.

There is perhaps an elision here between ascribing the rights of a company to its shareholders and considering whether the rights as they appear on paper fairly represent the rights as they are in reality

To return to the facts in RBC, there was no allegation that the contractual arrangements were shams, even if the result was that Sulpetro UK became a mere economic shell. On the facts, the parties clearly intended that Sulpetro UK should hold the licence but not the economic risk and reward, and the majority found no reason to depart from this position. Indeed, a number of comments in the judgment suggest that the majority may not have had much sympathy for HMRC given the structure reflected requirements imposed by the UK Government. The question was therefore whether those contractual arrangements had the effect of vesting in Sulpetro Canada the right to work the Buchan Field, which the majority answered in the negative.

In this, the majority decision in RBC appears to follow the approach taken in the Ramsay line of cases: the commercial (albeit not arm's length) intention was to create a split between the right to work and the right to profit from that work, and this was achieved by the contractual arrangement. Where the legal and commercial reality aligned Ramsay did not apply to usurp that.

Viewed this way, Lord Briggs perhaps does not take such a different approach. Where his judgment differs is in concluding that the Illustrative Agreement 'amounted to an outright transfer from Sulpetro (UK) to Sulpetro [Canada] of the whole of the economic benefit (and burden) of the licence. If it fell short of a full legal assignment or sub-licence it did so only as a matter of legal form, and the shortfall did not disturb the substance of that transfer, viewed realistically'. That is, in Lord Briggs' view the commercial intention was not to separate the right to work and the right to profit from that work, but in essence to vest the right to work in Sulpetro Canada, and he considers that the contractual arrangements, viewed realistically, together with the legal ownership, were effective in doing so.

If the majority can be taken as tacitly following Ramsay in this way, the majority decision could suggest that the threshold for what constitutes a 'realistic' view of the facts is higher than perhaps previously thought, such that it is difficult to disregard on a Ramsay basis anything less than an outright sham, even if commercially irrational. However, given the majority expressly says that 'nothing in this judgment casts doubt on the efficacy of those [Ramsay] principles where they apply', it appears unlikely that this was the intended reading of this part of the judgment.

Possibility 4: a purposive reading of Article 6 was not broader than a narrow reading

Even if this were the case, it may not be as significant for a Ramsay analysis as it first appears; the 'realistic' view of the facts must still be informed by a purposive analysis of the relevant provisions.

Again, the majority appears to follow this approach (at [94]) in considering what is meant by the 'right to work':

'The question is therefore whether there is anything in the UK/Canada Convention which indicates that one must identify the right to work and attribute that right to the entity which invests its funds and sells the oil, even if that is not the entity which is licensed by the Government. I do not see that there is.

Government. I do not see that there is.' In this context, the focus on legal personhood, and whether the corporate veil may be pierced, speaks to whether the purpose of Article 6 was to capture both direct and indirect rights in a natural resource (or direct rights, together with the economic benefit arising from those rights).

The Supreme Court concludes that, even if Sulpetro Canada had a 'right to work' the oil field within the meaning of Article 6(2), that right was still 'too remote' to fall within the expanded definition of 'immovable property'. This part of the decision may be strictly obiter, as the majority had already held that Sulpetro Canada did not have the 'right to work'. However, it may not be: a Ramsay-guided approach would involve both determining what the Article required purposively and determining whether the facts viewed realistically answered to that requirement.

The Court of Appeal construed Article 6 as applying only to 'rights to payments held by a person who has some form of continuing interest in the land in question to which the rights can be attributed', and not rights 'of a personal nature, held by a person who has no link to the physical land in question', although the requisite link was not necessarily limited to rights granted by the landowner.

While the Supreme Court rejected the proposition that Article 6 should be 'restricted to the initial grant or creation of a right or that it denotes only a right granted by the owner of an interest in the land', it appears to agree with the Court of Appeal that some form of continuing interest is required.

The consequence of this initially appears to be that even if the UK Government had granted the licence to Sulpetro Canada directly, two economically equivalent transactions would result in different tax treatment. If Sulpetro Canada retained the licence but assigned the economic risk and reward to BP, the consideration paid by BP would fall within Article 6; but if Sulpetro Canada transferred the licence to BP, the consideration would fall outside Article 6. However, perhaps this is justified in the context of the treaty, since that outright disposal would instead fall with Article 13.

Put another way, the rights under the Illustrative Agreement were derived from and parasitic on the primary right under the licence, and therefore reliant on the continued acquiescence of Sulpetro UK as licenceholder; a payment made by BP to Sulpetro UK would reflect that chain between the underlying resource and the rights. Conversely, the result of the actual transaction in RBC was that Sulpetro Canada dropped out of the chain, and so the consideration payable to Sulpetro Canada was one degree further removed from the resource and from the purpose of the Article.

Where does this leave us?

But for the apparent dismissal of Ramsay, you might say that in its general approach, the majority decision does follow the principles set out in that line of cases. Admittedly, that analysis is not linear, but the case law is firm that Ramsay is not a strict two-step test: 'this does not mean that the courts have to put their reasoning into the straitjacket of first construing the statute in the abstract and then looking at the facts. It might be more convenient to analyse the facts and then ask whether they satisfy the requirements of the statute' (Barclays) and, indeed, an iterative approach may be necessary.

In any event, it is disappointing that a decision of the Supreme Court should leave taxpayers so uncertain as to the state of the law

This permits the least damage to be done to the existing case law on Ramsay, by reading the majority decision as saying that there was nothing in the treaty to require, even on a purposive reading, an extension of Article 6 to economic rights, and nothing on the facts, even on a realistic view, to require the court to view Sulpetro Canada as having in effect the right to work the field. That is, Ramsay, being a recognition of a general rule of statutory interpretation and a departure from tax law's previous 'island of literal interpretation', always applies; the only question is to what extent it has any impact.

But this rests uneasily with the majority's statement that 'no one here' has suggested that Ramsay 'has any application to the present facts'.

In any event, it is disappointing that a decision of the Supreme Court should leave taxpayers so uncertain as to the state of the law. While this article seeks to reconcile some of the apparently disparate elements within the RBC decision, unless and until a later Supreme Court decision clarifies the point, it seems taxpayers will have to tolerate continued uncertainty as to whether the Ramsay principle can, or should, be applied only in particular circumstances.

Originally Published by TAXJOURNAL

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]