- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Healthcare and Retail & Leisure industries

- within Cannabis & Hemp, Law Practice Management and Privacy topic(s)

The battle against cheats and hacks is a serious challenge for games companies. A recent study as reported in GamesIndustry.biz suggests that 80% of players across both the UK and the US have experienced cheating in online games. There have also been multiple reports of publishers acting against cheating activity to protect the integrity of their online experience.

Our article (by Aaron Trebble, Adrian Aronsson-Storrier and Jemma Costin) on video game mods, hacks and cheats and the Sony v Datel dispute has just been published in the Interactive Entertainment Law Review (IELR). The IELR is the leading academic peer-reviewed journal for legal analysis of video games and digital interactive entertainment. This blogpost summarises the key takeaways from our article, provides guidance on the full range of legal tools that game developers can use to address cheats, and updates on recent related legal developments in Germany.

Imagine that you are a games developer or publisher. After years of hard work and financial investment, your game – complete with original animation, music, artwork, code and mechanics – is ready for release. It gains traction and grows a loyal player base ... and then player mods start to alter your designs; and cheats and hacks allow players to progress through your game in unintended ways or, worse, to disrupt the game's online multiplayer experience.

Whilst it is not always possible, or commercially desirable, to take action in the face of these activities, one option a gaming company might consider is intellectual property (IP) enforcement. The manufacture, distribution and use of mods, cheats and hacking software are likely to involve acts that may infringe copyright and will also often involve breach of the contractual terms set out in the game's End-User Licence Agreement (EULA).

The role of IP protection in addressing the risk of hacks and cheats was recently considered in the EU in the Court of Justice decision in the long running Sony v Datel dispute. This blog post considers the implications of the CJEU decision on the protection of video games under the Software Directive, as well as the other IP rights than can be used by a developer to protect their gameplay. For those who want a deeper dive into these issues, including a discussion of the two previous occasions where the UK High Court has considered the issue of copyright infringement in relation to mods, cheats and hacks, please read our longer article published in the IELR.

Mods, cheats, hacking software ... what is the difference?

Mods, or modifications, are alterations of one or more elements of a video game in ways not intended or enabled by the original developer. Mods are software add-ons to the base game and can range from minor cosmetic changes to extensive overhauls that add new content or change the gameplay mechanics. Examples include enhancements to lighting or texture, convenience mods such as auto-loot, and new content like new characters, skins, quests or, famously in the case of Skyrim, a mod that replaces dragon enemies with Thomas the Tank Engine. Mods are usually created for personalisation or enhancement in a single-player game but are occasionally used in multiplayer games either on a private server or with the consent of the developer. Many developers actively encourage mods to foster community engagement, but only if they comply with a game's EULA. Unauthorized mods that copy or redistribute game assets or code could be considered a breach of contract if contrary to the EULA and/or copyright infringement under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA 1988).

Cheats and hacks are activities which interfere with the integrity of the video game or the experience of other players. This includes tools or software that give a player an unfair advantage in the game, often in a multiplayer environment. These are distinguished from in-built cheats that are intended for player use by the developer of a game, such as the famous Konami Code. Cheating can involve altering local files or running unauthorized tools, codes or software to provide benefits like unlimited health or resources, auto-aim software or revealing hidden items in the game. Cheating may give rise to a breach of contract claim if it violates the EULA. It can also result in a copyright infringement claim if the software copies part of the game's code or other IP assets.

Sony v Datel – hacks before the CJEU

Following almost a decade of litigation in Germany, the CJEU in Sony v Datel was recently asked to consider whether, and in what circumstances, certain cheat tools can be used to circumvent game design without infringing copyright subsisting in computer programs under the EU's Software Directive (which has been implemented in the UK in the CDPA 1988). The case concerned Datel's 'Action Replay' software, which modified RAM variables in the PlayStation Portable console (PSP). The Action Replay software unlocked restricted features in PSP games that would otherwise only be accessible for players after obtaining a certain number of points. Rather than altering or reproducing the original game's source or object code, the Action Replay manipulated variables transferred to the console's RAM during gameplay.

At first instance in Germany, Sony was partially successful in its claim for copyright infringement. That decision was reversed on appeal and, on further appeal to the Bundesgerichtshof (the German Federal Court of Justice), the proceedings were stayed while the Court referred questions of legal interpretation of the Software Directive to the CJEU. The key question that was referred to the CJEU was whether altering the value of a game variable without copying or changing the game code infringe copyright in the code?

Under Article 1(3) of the Software Directive, the expression of a computer program (but not its underlying ideas and principles) is protected as a literary work if it is original in the sense that it is the author's own intellectual creation. The CJEU recited previous case law confirming that it is the source code and the object code specifically which are protected, as it is the code that constitutes the expression of the computer program. Other elements of a computer program, such as the functionalities and its user interface, are not protected through the Software Directive.

The CJEU decided that altering RAM variables does not involve copying or altering original elements of the game's code and, as a result, such modifications fall outside the scope of copyright infringement under the Software Directive. As a result, the Action Replay tools marketed by Datel did not infringe.

Implications of the CJEU decision

While Sony v Datel establishes that copyright in video game code protected under the Software Directive may not extend to the values of variables, its potential impact on a games company's ability to control hacks and cheats should not be overstated. For example, the CJEU did not resolve the question of whether a change to the value of variables, which causes copyright protected content to be temporarily instantiated in the cheater's game, is infringing under the Copyright Directive – something which had arisen in earlier UK litigation in Take-Two v. James, discussed in our full article.

Effective policing of cheats, hacks and mods requires a combination of technical, legal and community measures. The most successful strategies will involve robust anti-cheat systems, active monitoring of player activities to detect signs of third-party software, clearly drafted and enforceable EULAs and a comprehensive policy for identifying, protecting and enforcing intellectual property rights.

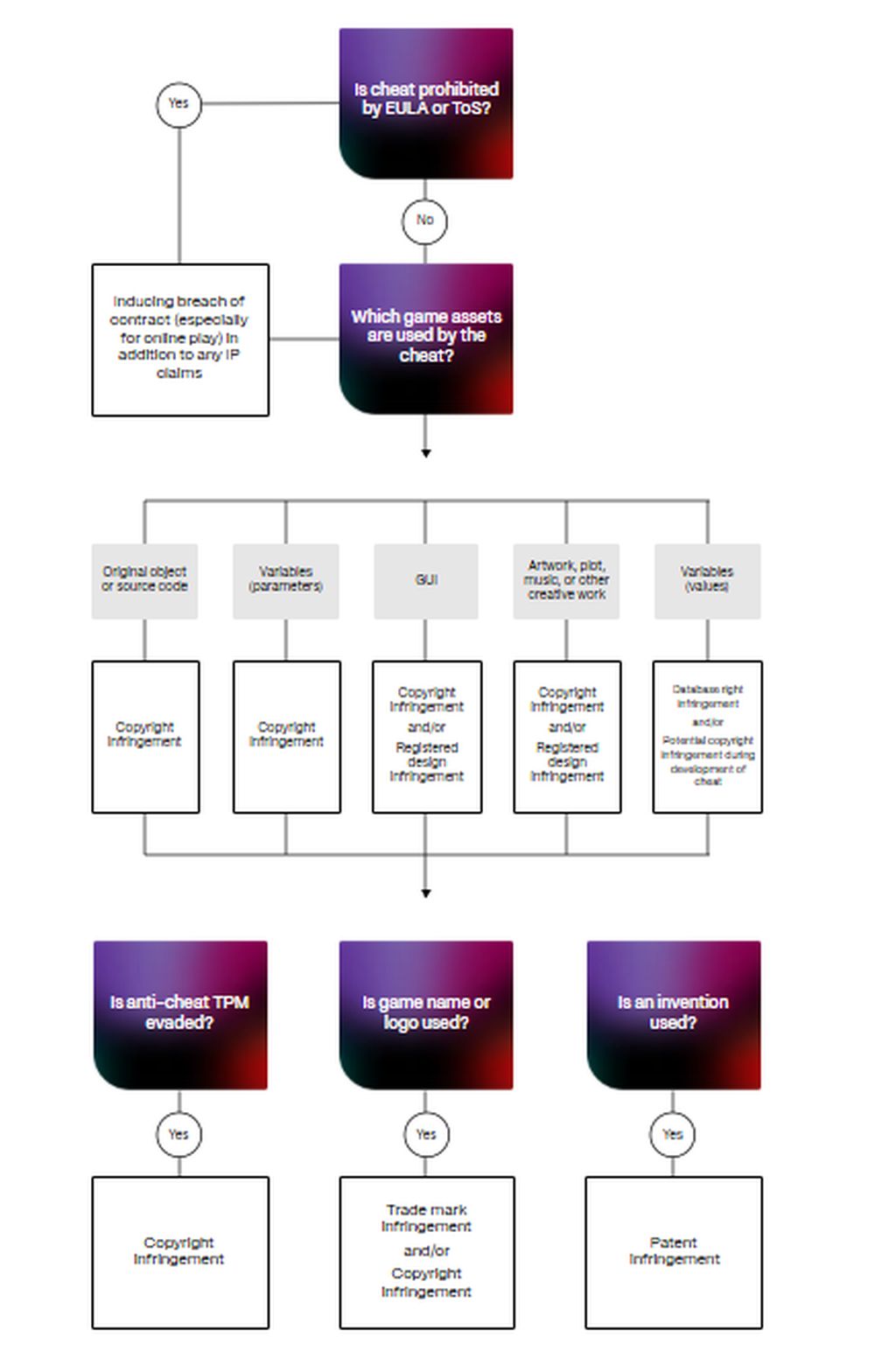

Whilst identifying claims in breach of contract and copyright infringement will often be straightforward with cheats, hacks and mods (particularly in an online environment), it is important to be aware of the various potential claims, which may exist in a given case, including in respect of database rights and registered intellectual property rights such as patents and trade marks. Such rights may be helpful in a case where there is not a clearly identifiable infringement of copyright. It is also important to consider intellectual property infringement which may have occurred during the development of the cheat or hack, and not just that which occurs whilst it is being used with the video game.

Our flowchart exploring the various legal tools available for a video game developer to take action against an unauthorised mod, hack or cheat is below. The considerations relevant to the deployment of each alternate legal remedy to combat hacks and cheats are discussed in our full article.

Recent developments in Germany

Following the finalisation of our article, the Sony v Datel dispute returned to the Bundesgerichtshof for further hearing and for the Court to apply the interpretation of the Software Directive which had been elaborated by the CJEU. In applying the CJEU's decision, the Bundesgerichtshof confirmed that the action replay software only altered the values of variable data stored in the console's RAM, and not the program commands of the game software. As a consequence the defendant's activities were outside the scope of protection of Article 1 of the Software Directive (and domestic German legislation implementing the Directive in section 69a of the German Copyright Act), and Sony's appeal was dismissed. This brought to an end the long running saga of this litigation, which had been commenced in 2012.

Some of the more complex and unresolved questions about the implications of the CJEU decision discussed in section 2.3.5 of our full article were sadly not addressed by the Bundesgerichtshof, and will need to wait to be clarified in a future decision. The German Courts may however soon have such an opportunity in the Adblocker IV litigation. The Bundesgerichtshof handed down a judgement in that dispute on the same day as the Sony v Datel dispute, overturning a decision of the Hamburg Higher Regional Court and referring the dispute back to the lower court to resolve.

The Adblocker case similarly considers the scope of protection available under the Software Directive, and the decision explicitly refers to the CJEU decision in Sony v Datel. In the Adblocker dispute a German online media company Axel Springer brought action against the developer of ad blocker software "Adblock Plus". The publisher claimed that the commands in the website HTML files used to give instructions to web browser on the display of their news websites are a computer programs within the meaning of the Software Directive. They argue that the modifications made by the ad blocker software on the data structures generated by a user's browser when parsing the HTML code (carried out to prevent adverts from displaying) were unlawful modifications of their computer program. The Bundesgerichtshof considered that the factual findings previously made by the German Court of Appeal were insufficient for resolving the dispute, as it was unclear whether the ad blocker merely interfered with the execution of the HTML code or whether instead protected program commands were blocked and overwritten and the protected computer code was actively and directly changed. The eventual resolution of the Adblocker dispute may address some of the unresolved questions following the Sony v Datel CJEU decision, and will have implications for not only games companies, but more generally for the providers of cloud-based software.

Conclusion

As discussed above, while the CJEU and subsequent Bundesgerichtshof decisions in the Sony v Datel dispute establish that copyright in video game code protected under the Software Directive may not extend to the values of variables, the case's potential impact on a games company's ability to control hacks and cheats should not be overstated, given the range of other legal tools that a games developer can use to address hacks and cheats.

A balanced approach to enforcement is also recommended. Developers should seek to maintain a dialogue with their player communities on modding and cheating issues. Permitting some activities, such as controlled modding within suitable single-player environments, may encourage a positive relationship with the player base that can enhance a game's longevity and reputation. By balancing enforcement and engagement, developers can safeguard their IP whilst supporting the community and creativity that defines the gaming industry.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.