- within Cannabis & Hemp, Law Practice Management and Transport topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

The High Court has recently considered whether an exchange of WhatsApp messages can create a contract.

Jaevee Homes v Fincham [2025] EWHC 942 (TCC) arose from a dispute between a property developer, Jaevee Homes Limited ("the developer"), and demolition contractor Mr Steve Fincham ("Steve") regarding the terms of a construction contract.

The parties had agreed that Steve would carry out demolition work, but they disagreed over the terms of their agreement. They had started negotiating via email and then moved to WhatsApp messages. Steve argued that a sub-contract with the developer was formed by this exchange of WhatsApp messages. The developer countered that a sub-contract had been agreed based on its standard terms of business, having sent Steve these standard terms after the WhatsApp exchange but before Steve started work.

Steve started the demolition work on 30 May 2023 and completed it by July. The developer failed to pay any of his four invoices in full. Following a disagreement over the amount of work Steve had completed, the developer purported to terminate the sub-contract that was (supposedly) based on its standard terms of business. The developer also argued that the four invoices Steve had submitted – on 9 June, 23 June, 14 July and 27 July 2023, totalling almost £200,000 + VAT – did not comply with its standard terms of business and were therefore invalid.

After a complex background of legal proceedings, the dispute ended up for consideration before Judge Roger ter Haar in the High Court.

How was a contract formed?

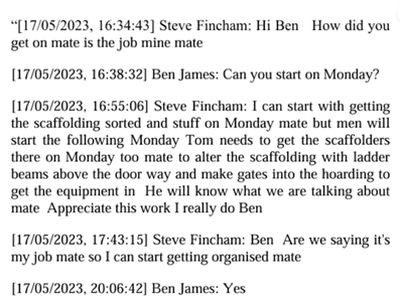

Judge ter Haar found that the parties had agreed a contract by the following exchange of WhatsApp messages:

The judge said that this exchange, "whilst informal, evidenced and constituted a concluded contract". There was by this point clear agreement on the identities of the parties, on the scope of the works that Steve was to perform and on the price. These being sufficient to bring a contract into existence, the developer's reply "Yes" brought a contract into existence.

The judge went on to find that the parties had also agreed payment terms (monthly payment applications using invoices) but that this was not essential to create a contract. And, if the parties had not considered the payment terms, legislation would in any event have implied payment terms into the sub-contract, it being a construction contract (on which, see below).

The developer had argued that there was no agreement on the duration of the works. The judge commented that this was not essential to form a contract, noting that the law implies a term that the contractor will complete their work within a reasonable time.

The developer had also complained that no start date had been agreed. The judge said that a precise start date was not "an essential term of the contract". It was therefore not needed to create a binding sub-contract.

Peculiarities of construction contracts

In isolation, this case may not seem especially noteworthy. It is well established that contracts can be concluded without much formality. Provided the usual tests are met (clearly identified parties, agreement on what is to be done, consideration such as a promise to pay a price, an intention to create legal relations and sufficiently certain material terms), there is no legal principle against concluding a contract through WhatsApp messages.

However, this case is particularly interesting for businesses involved in the construction sector. It highlights the significance of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 ("the Construction Act"). Just as the Consumer Rights Act 2015 implies terms into consumer contracts – such as that goods sold must be of satisfactory quality and as described – that are not necessarily in the parties' minds when concluding a consumer contract, so the Construction Act implies important terms into construction contracts. Many terms.

Part II of the Construction Act defines what a "construction contract" is. This is broader than you might expect. It encompasses, not just stereotypical building work, but also professional services (such as landscape design) and a plethora of other activities, such as painting or the fitting of air conditioning – except contracts with residential occupiers.

Until 2011, "construction contracts" had to be in writing. That is no longer the case. Now, even oral construction contracts, such as Steve's sub-contract, are captured by the Construction Act.

The Construction Act implies a unique right to refer disputes to an adjudicator. This is the right that Steve used to bring a – successful – adjudication against the developer to enforce his four payment applications, which the developer then sought to challenge in the High Court, including before Judge ter Haar.

Adjudication, which applies only to construction contracts (and to other forms of contract where parties have expressly opted in), is a rapid and (compared to litigation in the courts) low-cost method of resolving disputes. Each party must pay its own costs and the process is widely regarded as effective. Very rarely do courts allow appeals from adjudicators' decisions. Instead of a judge deciding the dispute by following the courts' usual slow timescales, an independent adjudicator reaches a decision within weeks of a dispute being referred to them. Adjudicators are often construction professionals such as quantity surveyors, rather than lawyers.

If a construction contract does not contain written provisions regulating the adjudication process – such as oral contracts and Steve's WhatsApp contract – rules are implied by the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998 ("the Scheme"). Additionally, the Construction Act tightly regulates payments in construction contracts. Where parties do not expressly agree payment terms, comprehensive terms are implied by the Scheme.

In Steve's case, the developer had sought to argue that no contract could have been formed by the exchange of WhatsApp messages because of an (alleged) absence of terms regulating the payment process, and that instead its standard terms of business applied. Because Steve had not complied with the stringent payment provisions of those standard terms, this argument would have allowed the developer to set aside the payment applications that Steve had enforced via adjudication.

The judge dismissed the developer's arguments, noting that comprehensive payment terms are implied by the Scheme and that Steve, in making payment applications by issuing his invoices, had complied with those implied terms. Therefore, three of Steve's four payment applications were valid. (The fourth was invalid because Steve had made two applications that month, and the judge found that the parties had agreed in their WhatsApp messages that a maximum of one payment application would be made in any monthly payment cycle. Notwithstanding this, Steve was the successful party overall, having succeeded on every other point.)

What does this case mean for you?

This case provides a timely reminder of the ease with which contracts can be created. In the construction sector and other areas with complex legislation, such as the processing of personal data, these can automatically be subject to a wide range of unfamiliar terms and processes.

As a business, it is important to make sure that you know when you have formed a contract. To avoid creating contracts unexpectedly:

- ensure that, wherever possible, your staff use work emails and not social media channels

- make sure all communications – both written and oral – are stated to be "subject to contract"

- require your staff to document business arrangements properly and refer all new relationships through your business' legal team

- where you intend to conclude a contract, ensure that you formalise its terms and conditions in writing, and include an "entire agreement" clause that prevents pre-contract negotiations and communications from influencing the contract's terms

- if your business operates in sectors such as IT or construction where it is common practice to start some work before the final contract has been fully agreed, use letters of intent or similar such arrangements to formalise the terms that apply to those initial services before the final contract is agreed and signed.

If in doubt – and particularly if a new contract might be a construction contract and you are unfamiliar with the Construction Act's requirements – seek legal advice. At Lewis Silkin, we have experts in construction law, data law and a plethora of other areas. They are ready to help your business comply with the law's requirements and avoid costly mistakes.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.