4.5. Transfer pricing and attribution of profits to a permanent establishment

4.5.1. Morgan Stanley case

Under Art. 7 of both the OECD Model Convention and UN Model Treaty, a foreign enterprise is liable to tax in the source country on its business profits which are attributable to the PE in the source country This provision specifies how such business profits should be ascertained, and states that a PE is to be treated as if it is an independent enterprise (profit centre) apart from the head office and which deals with the head office at arms length. Therefore, its profits are determined as if it were an independent enterprise. Art. 7(2) of the UN Model Treaty advocates the arms length approach for attribution of profits to a PE. Under Art. 7(2), economic nexus is an important issue of the principle of profit attribution to a PE. Therefore, in the Morgan Stanley case the Supreme Court held that only the profits of MSCo that have an economic nexus with the PE in India are taxable in India.

The Supreme Court came to an important conclusion signifying that because MSCorendered services to MSAS through the employees it seconded to MSAS, MSCo had a service PE in India through MSAS, that is, MSAS is the service FE of MSCo. The Supreme Courts conclusion that the service PE and the service provider are one, and thus the subsidiary, MSAS, constitutes the service PE, adds another dimension to the case, because generally it is understood that only in the case of an agency PE does the agent constitutes a PE of the foreign enterprise. This important distinction must be kept in mind, as the concession granted by the Supreme Court decision is based on this important conclusion, which is discussed below.

Thus, the Supreme Court held that because the remuneration to MSAS was justified by a transfer pricing analysis, no further income could be attributed to the PE, i.e. where an associated enterprise that also constitutes a PE (in this case, MSAS) is remunerated on an arms length basis, taking into account all the risk-taking functions of the enterprise (the PE), no further profit is attributable to the PE. However, where the transfer pricing analysis does not adequately reflect the functions performed and the risks borne by the enterprise, it would be necessary to further attribute profits to the PE for those functions/risks that have not been considered. This determination would depend on the functional and factual analysis undertaken in each case. It was further held that the TNMM is the appropriate method for determining the arms length consideration in the transactions between MSCo and MSAS.

The above indicates that the tax liability of a non-resident entity is extinguished if an associated enterprise (that also constitutes a PE) is remunerated on an arms length basis, taking into account all the risk-taking functions of the enterprise (PE). As such, this decision will apply only in those cases where the PE is also constituted by the functioning of the associated enterprise and the associated enterprise is remunerated on an arms length basis after taking into account all the risk-taking functions of the PE, i.e. the functions performed and risks borne by the PE are appropriately captured by the associated enterprise.

In the Morgan Stanley case, it seems that the Supreme Court has adopted an approach that is almost similar to the single-taxpayer approach for the attribution of profits which is in contrast to the authorized approach of the OECD; indeed the judgment leaves room for further profits to be attributed to a PE if the factual and functional analysis of the associated entity does not fully capture the functionality of the PE. The OECD Report on the Attribution of Profits to a permanent establishment provides that, for tax purposes, in the source country there are two taxpayers, namely the dependent agent (resident) and the dependent agent PE (non-resident). The functions carried out and the risks borne by these two are to be considered and compensated separately In the source country two separate tax returns must be filed, one for the dependent agent (resident) and one for the non-resident (PE). The OECD Report also suggests that the source country could have the right to tax the dependent agent PE even where the dependent agent has been compensated by an arms length consideration. Para. 279 of the OECD Report reads as follows:

Attention is also drawn to the two-step process13 enunciated by Australian Taxation Ruling TR 2001/11, which states that Australias PE attribution rules use a two-step process to apply an arms length separate-enterprise principle in attributing profits to a PE:

Step 2: Undertake a comparability analysis, which determines an arms length return for the FAR attributed to the PR

The Australian tax administration has clarified that this process applies to all PEs, including dependent agent PEs. In performing this process, it is critical to properly distinguish between two different taxpayer enterprises with different FAR and, invariabl)c different taxable profits, that is:

- Foreign Company, through its dependent agent PE,

and

- Subsidiary Company, through its agency

activities.

The FAR of the dependent agent PE are the FAR for Foreign Company, not Subsidiary Company, in respect of the agency activity. The dependent agent PE is attributed profit of Foreign Company, not Subsidiary Company, arising from the agency activity. Thus the profit attributable to Foreign Companys dependent agent PE is not merely an arms length profit for the agent activity. Rather, it is an arms length profit for the FAR of Foreign Company in respect of the agency activity performed by Subsidiary Company on behalf of Foreign Company.

The taxable profit of the dependent agent PE is calculated by taking some part of Foreign Companyc income from the activity performed by the agent and deducting the expenses (including the service fee paid to Subsidiary Company) Foreign Company incurs in deriving that income. Accordingly, while an armc length service fre paid by Foreign Company may be an armc length re wa rd for the agentc FAR, it does not follow that it also constitutes the armc length rewardfor the dependent agentc PEc FAR14

However, the Supreme Court held in the Morgan Stanley case that the tax liability of the non-resident entity is extinguished if an associated enterprise (that also constitutes a PE) is remunerated on an arms length basis, taking into account all the risk-taking functions of the enterprise. This means that this decision will apply only in those cases where the PE is also constituted by the functioning of the associated enterprise and the associated enterprise is remunerated on an armc length basis after taking into account all risk-taking functions of the FE, i.e. the functions performed and risks borne by the PE are appropriately captured in the associated enterprise. It seems clear that the Supreme Court dissented from the view expressed by the OECD Report that, the payment of arms length remuneration does notnecessarily extinguish the tax liability of the non-resident in the host country.

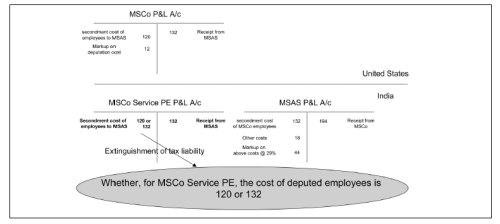

However, an analysis of the decision of the Supreme Court reveals that the concession is granted with a caveat that the associated enterprise should completely "capture the factual and functional analysis of the PE Then and only then will the concession of the decision apply, namely that if the associated enterprise also comprises the PE of the foreign enterprise (which is likely only in two scenarios, i.e. agency PE and service PE), then if its factual and functional analysis also encompasses the same of the PE, the arms length return earned by the associated enterprise extinguishes any further profit attribution to the PE of the foreign enterprise. The example below (based on the facts in Morgan Stanley) explains how the PE attribution is nil if the functionality of the PE is captured by the associated enterprise.

4.5.2. Tribunal Ruling in SET Satellite case

In Dy Director of Income Tax v. SET Satellite (Singapore) Ftc Ltd,15 the Mumbai Tribunal took a contrary view that the income of a foreign company in India may be taxed even where the foreign company pays an arms length remuneration to its dependent agent in India. In this case, SET Satellite (Singapore) Pte Ltd (SET Satellite) was a foreign telecasting company resident in Singapore. SET

Satellite was in the business of creating and operating satellite television channels, marketing and distributing such channels in India and providing related support services to Indian customers. SET Satellite appointed an agent in India to market air time slots to various advertisers in India on its behalf. The agent in India constituted a PE of the taxpayer in India, and SET Satellite remunerated the agent on an arms length basis for the services rendered with regard to the marketing of air time. The Indian assessing officer determined that SET Satelliteearned income taxable in India and computed the tax base at 10% of the advertisement revenue. However, the Commissioner of Income Tax (Appeals) accepted the taxpayers argument that because the remuneration was on arms length terms, it had no further tax liability in India. The tax authorities further appealed to the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (Tribunal).

The Tribunal first concluded that a dependent agent and a dependent agent PE (or DAPE) are distinct entities. A DAPE is not the dependent agent per se, but rather a DAPE exists (hypothetically) by virtue of an enterprise having a dependent agent. Under Art. 5(8) of the India Singapore treaty, where an agent, other than an independent agent, satisfies at least one of the tests set out in Art. 5(8), the enterprise will be deemed to have a PE in the other contracting state. Thus, the Tribunal held that the profits attributable to the PE under Art. 7 of the treaty are the profits of the foreign company and not those of the dependent agent. Mere payment of arms length remuneration to a dependent agent does not necessarily extinguish the tax liability of the foreign company in India. The Tribunal stated that a DAPE is a hypothetical establishment, the taxability of which depends on the income from the activities of the foreign company that are attributable to the PE, which in itself is based on the functions performed, assets deployed and risks borne (FAR) by the foreign company with regard to the activities carried out in India. In other words, the income generated as a result of the functions performed, assets deployed and risks borne by the DAPE is considered the "hypothetical" income of the DAPE, with a deduction allowed with regard to all expenses incurred by the foreign company, including any remuneration paid to the dependent agent.

The Tribunal rejected the taxpayers arguments that it should take into consideration the 2006 ruling of the AAR in the Morgan Stanley case, where the AAR ruled that the payment of arms length remuneration by a foreign enterprise to its dependent agent does extinguish the tax liability of the foreign enterprise in India. The Tribunal stated that AAR rulings apply only in the context of the taxpayer to which the ruling was issued, and therefore are not binding in the case at hand.

However, the Supreme Court has taken a contrary view in its judgement in the Morgan Stanley case and therefore, it seems that the above decision of the Mumbai Tribunal has now been overruled by the Supreme Court in Morgan Stanley with regard to the issue of whether the payment of an arms length remuneration by a foreign enterprise to its dependent agent does extinguish the tax liability of the foreign enterprise in India, in the limited factual pattern noted above. The decisions concession as regards the attribution of profits to a PE should be interpreted in the facts of the case, and cannot be said to set forth a universal norm. It would be painting too broad a brush stroke to specify a principle that an arms length return earned by an associated enterprise always extinguishes the possibility that any further income will be attributed to the foreign enterprises PE. Thus, it is necessary to consider the fact pattern of each case and apply the principles emerging from this case.

4.5.3. Recent Tribunal Ruling in Galileo case

In a recent decision of the Delhi Tribunal in the Galileo International Inc. case,16 the Tribunal observed that Gil had availed itself of the services of Interglobe to promote the use of CRS in India and for that purpose to recruit travel agents in India. The Tribunal held that Interglobe could be said to have exercised an authority to conclude contracts on behalf of Gil and Interglobe thus should be treated as an agent of Gil in India because:

- Interglobe was authorized to enter into contracts with the subscribers and Gil was bound by the bookings made by subscribers using the CRS; and

- reservations and ticketing carried out using the CRS products were honoured by the participants (airlines etc).

Therefore, the Tribunal ultimately held that Gil has both a fixed-place PE and an agency PE in India.

As regards the attribution of profits, the Tribunal found that only part of the CRS operated in India. The work in India was only to the extent of generating requests and receiving the end result of the process in India. The major portion of the work was processed at the host computer in the United States; Indian activities were only a minuscule portion. The Tribunal found that the majority of the functions were performed outside India. Even the majority of the assets (e.g. the host computer) was outside India. The CRS was developed and maintained outside India. The risk, in this regard, remained entirely with Gil in the United States, i.e. outside India.

On the basis of this function, asset and risk analysis, especially considering the value situated outside India, the Tribunal attributed 15% of the revenue accruing to Gil with regard to bookings made in India as income accruing or arising in India. The Tribunal further observed that, broadly, Gil paid 33.3% of its gross revenue from income arising on account of bookings from India to its agent in India (i.e. Interglobe). Thus, with regard to the activities carried out in India, and considering the income accruing in India, the remuneration paid to the Indian agent consumed the entire income accruing or arising in India. The Tribunal noted that the entire payment made by Gil to Intergiobe had to be allowed as an expense in computing its total income (implying that such payment was arms length). Relying on the Supreme Court ruling in the Morgan Stanley case, the Tribunal held that no further income of Gil was taxable in India.

5. Conclusion

The Supreme Court decision in Morgan Stanley tends to bring out the various nuances emerging from constantly changing economic scenarios, where the rapid pace of information and telecommunication technology constantly challenge the traditional concept of interpreting the PE article under an applicable treaty. It is necessary to tread cautiously when applying the rationale of the Supreme Court, as sometimes both taxpayers and tax authorities would like to read too much in a ruling in seeking to attain their desired result. Tax practitioners have probably not heard the last on this matter, and it would be interesting to see how lower courts will interpret this judgement, and more importantly, how they will apply it to the various fact patterns in cases brought before them in future.

The factual and economic analysis seems to be the underlying methodology, for both interpreting the PE article and determining the profits to be attributed to the PE. The analysis would help one to understand the economic substance of the transactions and would thus pave the way for attributing equitable economic profit to that economic substance.

This case could provide guidance to the OECD and other nations in developing principles of tax treaty interpretation which have the flexibility to embrace new business models in an ever evolving economic world order. If the PE article or in fact income tax treaties are to have relevance and meaning in todays changing global economics, their must be a fair and equitable distribution of revenue to both the residence and source state. Otherwise, like all rigid and indifferent behaviour, treaties may lose all relevance and be consigned to the library racks to gather dust. It is most likely time for all nations to develop principles that are common, and therefore necessarily equitable, if there is in fact a desire to reign in expansive interpretations which nations may employ to garner more tax revenue, and endanger the very philosophy on which the treaties are founded (namely the equitable sharing of taxes and the avoidance of double taxation).

It most likely is also time for the OECD to recognize the value contributed to the complete commercial process by the source states in the earning of profit by enterprises in the residence state. This recognition would probably allow the free play of economics to attribute an arms length profit to the enterprises of both the states, based on the economic value contributed by the enterprises, and not based on "old world" traditional concepts which have no relevance in the economic reality of today.

It is also important to understand the nuances of the arms length standard, and not use it as a panacea for all ills, because when the arms length standard is applied in a transfer pricing scenario, its purpose is to test whether the related-party transactions reflect arms length behaviour and fall within a range of comparable scenarios, and thus has a distinctively defensive colour. However, when the same standard is applied in a PE scenario, the focus changes from a testing standard to a profit attribution standard, and thus it becomes a more exacting standard from the perspective of taxing the foreign enterprises income in the source state. In such a scenario, it would be necessary to attribute profit for the subtle differences in the economic profile of the PE as measured to comparable companies. Thus, additional risks and functions of the PE need to be further compensated. It is these subtle differences which may require international consensus if the arms length standard is to be globally acceptable in a PE context.

If the OECD and other bodies do not change with the times, the importance of income tax treaties may become lost in international tax jurisprudence, for the foundation and consensus among nations would be shaken. One is reminded of Thomas Carlyles words, "Today is not yesterday We ourselves change. How can our works and thoughts, if they are always to be the fittest, continue always the same? Change, indeed is painful, yet ever needful, and if memory has its force and worth, so also hope

The key aspects of the Supreme Court decision are as follows:

- Determination of a FE. Where the activities of the associated enterprise and the subsidiary are intertwined and the associated enterprise participates in the economic activities of the subsidiary, the activities of the subsidiary are to be analysed to determinewhether there is a fixed-place PE.

- Attribution of profits to a FE. If a non-resident compensates its India subsidiary (which is also a PE) in line with the arms length standard, no further profits are attributable in India. Service charges payable to the service provider must fully represent the value of the profits attributable to its services.

- Basis of the armc length price. First, ascertain whether the income and expense (cost) allocation of or to the subsidiary is at arms length. The arms length price is to be determined after taking into consideration all the risk-taking functions of the multinational enterprise (PE).

To return to the first part of the article click here.

Footnotes

12. Emphasis added.

13. Product ID 143149.2005; www.ato.gov.au.

14. FR 2001 / 11, (emphasis added).

15. 108 TTJ 445.

16. See 4.1.2.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.