- in United States

- within Government, Public Sector, Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring and Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Utilities and Law Firm industries

Taxation, a structured process to fund public welfare, includes direct and indirect taxes governed by the Income-tax Act, 1961, and the Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017. This article explores the concepts of exemptions and deductions in tax law. Exemptions exclude entire incomes or transactions from taxation, focusing on the taxpayer's nature, while deductions reduce taxable amounts based on qualifying expenses. These provisions, upheld by courts, aim to promote social policy, equity, and economic efficiency. Despite concerns of discrimination, they ensure fair and equitable taxation, addressing diverse taxpayer circumstances and adhering to constitutional mandates.

Introduction

Taxation is a structured process where individuals and entities are obligated to contribute a portion of their income or profits to the government. The fundamental objective of taxation is to enhance the government's revenue streams for public welfare initiatives. These funds collected are reinvested for the public's benefit.

Tax laws comprise a plethora of regulations, including statutes, rules, orders, and circulars issued by authorities. Notably, the Income-tax Act, 1961 ('IT Act'), governs direct taxes, while the Goods and Services Act, 2017 ('GST Act') oversees indirect taxes. The components of tax primarily include the nature of the taxable event, the person on whom the levy is imposed, the rate at which tax is imposed, and the measure or value to which the rate will be applied for computing the tax liability.1

This article delves into a crucial aspect of taxation laws: Exemption and Deduction. It elucidates the concepts of exemption and deduction, exploring the provisions associated with these aspects, along with pertinent cases that underscore the constitutional validity of these provisions, particularly in light of a. 14 of the Constitution of India, 1949 ('Constitution').

Exemption & Deduction: Definitions & Differences

An 'exemption' in legal parlance denotes liberation from certain obligations or responsibilities. In the context of tax laws, exemption signifies the granted privilege or freedom from the obligation to pay a specific duty or tax as stipulated by the laws. An exemption represents a legal deduction from the taxable income for qualifying reasons. In income tax law, exemptions refer to income excluded from the total taxable income. Exemptions also serve the public good under the GST Act by excluding certain transactions of goods and services or taxable persons from the scope of supply, thereby ensuring their non-taxability under GST regulations.

On the other hand, tax deductions involve the reduction of a portion of income, expenditure, or investment from the total taxable amount. These deductions are typically permitted for specific activities. For example, if an individual purchases insurance policies or repays a loan, the corresponding amounts are deducted, leaving only the remaining income, expenses, and investments subject to taxation. Essentially, the purpose of tax deductions is to incentivize individuals to save money and invest in such activities.

Tax deductions offer numerous benefits that extend beyond just reducing tax liability. They serve as incentives for charitable contributions, stimulating investment, promoting homeownership, and facilitating education and skill development. By incentivizing these activities through tax deductions, governments encourage individuals and businesses to engage in behaviours that contribute to societal well-being, economic growth, and individual prosperity.

When considering both exemption and deduction in taxation, they may appear similar, but significant differences exist between them. Tax exemption involves excluding entire income or transactions from taxation, while deduction involves excluding only specific aspects of income or transactions from taxation.

Tax exemptions typically revolve around the nature of individuals and entities. For example, tax exemptions are often granted to non-profit organizations. Therefore, tax exemptions are generally more focused on who receives them. In contrast, tax deductions primarily focus on the qualifying transactions or expenses for which deductions are allowed. Moreover, under exemptions, income or transactions are directly removed from the scope of taxable income. Conversely, under deductions, taxable income is indirectly reduced after deducting qualifying expenses.

Provisions Allowing for Exemptions & Deductions

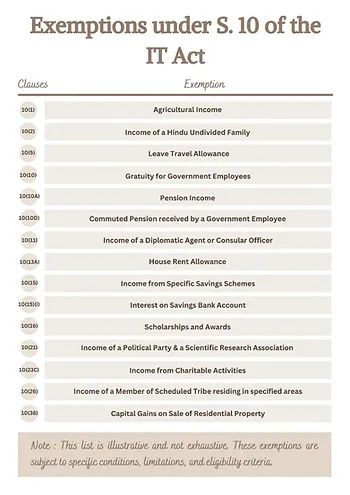

The IT Act and the GST Act provide extensive provisions for exemptions and deductions. For instance, s. 10 of the IT Act outlines incomes that shall not be considered when computing income tax, providing exemptions for various types of income such as house rent allowance ('HRA'), travel allowance, and income earned by scheduled tribe members in certain states, among others.

Similarly, the GST Act also provides exemptions for certain goods and services. For instance, certain goods such as vegetables, live trees and plants, natural products, seeds, sugars, water, etc. are exempted from the imposition of GST. Likewise, services like agricultural services, government services, medical services, and educational services are also exempted from the GST. The GST Act also provides exemptions to businesses and individuals whose turnover falls below specified limits:

- For supply of goods: Rs. 40 lakhs (or Rs. 20 lakhs in hilly and northeastern States).

- For supply of services: Rs. 20 lakhs (or Rs. 10 lakhs in hilly and northeastern States).

Reasons for GST exemptions include social welfare, support for small businesses, promotion of exports, simplification of interstate supplies, encouragement of agriculture, exemption for certain government and financial services, respect for cultural and religious values, administrative simplicity, and transitional provisions during the migration to GST.

Similarly, s. 80 of the IT Act lists out provisions allowing for deductions. These include deductions for investments, contributions to pension schemes, medical treatments of dependents with disabilities, interest paid for education loans, donations made to specified funds and charitable institutions, and more.

The provisions mentioned here represent only a selection of prominent exemption and deductions clauses, due to the extensive nature of the list, it is impractical to include all provisions in this discussion.

When filing their income-tax return ('ITR'), individuals claiming exemptions and deductions must accurately specify the amount of income under the relevant income head. Failure to do so may result in the loss of entitled benefits unless a revised ITR is filed. Similarly, under the GST Act, when submitting the monthly summary of GSTR-3B, individuals must report the amount eligible for exemption from GST imposition. This ensures compliance with tax regulations and facilitates the proper utilization of available exemptions and deductions.

The philosophy behind exemptions and deductions is rooted in principles of necessity, social policy, equity, ability to pay, economic efficiency, and behavioural incentives. Exemptions often reflect social policy and equity considerations, allowing for certain types of income or transactions to be excluded from taxation due to their societal importance or the need for equitable treatment. Deductions, on the other hand, are often designed to reflect a taxpayer's ability to pay, encourage economic efficiency and investments, and incentivize certain behaviours.

Constitutional Validity of Exemptions and Deductions

Taxation laws derive their authority from a. 265 of the Constitution, which stipulates that taxes can only be levied through legal authorization. This encompasses not only the imposition of taxes but also the collection and assessment functions performed by authorities. However, all tax provisions must comply with other provisions of the Constitution, such as the requirement that laws must not be discriminatory and treat equals equally.2

Given this framework, it is natural to question whether exemptions and deductions that are not uniformly granted to all taxpayers could be considered discriminatory. If taxation is meant to be fair and non-discriminatory, then preferential treatment in the form of exemptions or deductions might seem to contradict this principle. Essentially, if certain individuals or entities receive tax benefits that others do not, it raises concerns about fairness and equality within the tax system. Therefore, the granting of exemptions and deductions should be carefully scrutinized to ensure they align with the overarching goal of non-discrimination in taxation.

The courts, through various decisions, have clarified that taxation laws do not require absolute equality in treatment. In the case of V. Venugopala Ravi Varma Rajah v. Union of India & Anr.3, the Court held that different rates of taxation for different categories of persons or objects do not necessarily violate the principle of equality under a. 14 of the Constitution. Further, the courts have opined that in taxation matters, the legislature has greater freedom not only to classify different persons or subjects but also to adopt different modes of taxation.4 Therefore, as long as tax provisions adhere to the fundamental principles of the classification test - where the classification is based on an intelligible differentia and the differentia bears a rational relation to the purpose of the legislation – they will not be deemed in violation of a. 14 of the Constitution, even if certain categories of individuals receive more favourable treatment than others.5

It is based on such understanding and position of law that the courts have upheld the constitutional validity of exemptions and deductions provided under the taxation law. In the case of Nath Bros. Exim International Ltd. v. Union of India & Anr.6, the division bench of the Delhi High Court upheld the constitutional validity of s. 80A(5) and 4th proviso to s. 10B(1) of the IT Act, observing those claiming benefits of deduction and those who are not, although both taxpayers are clearly apart. Thus, it is open to legislate and prescribe different conditions for those who claim benefits.

Similarly, in the case of Union of India & Ors. v. N.S. Rathnam & Sons7, the Supreme Court upheld the validity of notifications 102/87-CE and 103/87-CE both dated 27.03.1987, which exempted excise duty on iron and steel scrap obtained from breaking ships, but only for those who paid customs duty at a specific rate. The exclusion of individuals who paid customs duty at a lower rate was argued to be arbitrary and a violation of a. 14 of the Constitution, But the court upheld the notifications.

Similarly, in Shashikant Laxman Kale & Anr v. Union of India & Anr.8, the constitutional validity of s. 10(10C) of the IT Act, which provides tax exemption on payments received by public sector employees on voluntary retirement, was challenged. Such exemption was not extended to employees of private sector companies and this distinction between public and private sector employees was argued to be discriminatory. However, the court upheld the validity of the provision, stating that employees of the private sector do not fall into the same class as those of the public sector. It was held that the availability of such benefit exclusively to public sector employees did not make the classification arbitrary or invalid and therefore, the provision was deemed constitutionally valid.

Further, Rajan Bhatia v. Central Board of Direct Taxes & Anr.9, revolved around the constitutional validity of s. 115BBDA of the IT Act. The challenge was based on grounds of lack of a proper foundation or base and alleged discriminatory treatment between resident and non-resident assessees. The court while upholding the validity of the concerned provision observed that such classification was justified. It was reiterated that there is a presumption of constitutional validity for laws made by the Legislatures and that taxation statutes are generally not invalidated on grounds of under-classification.

The courts have emphasized that exemptions and deductions should not result in unjust benefits to individuals or a class of individuals. To maintain fairness, the court stresses the strict interpretation of exemption notifications, placing the burden of proving applicability on the assessee. Unlike in charging provisions, where the benefit goes to the assessee in case of ambiguity, in exemption notifications, any ambiguity is resolved in favour of the Revenue. Essentially, an assessee cannot claim exemption for income unless explicitly provided in the law.10

Conclusion

The Supreme Court emphasized in State of Kerala v. Haji K. Haji Kutty Naha & Ors.11, that treating essentially dissimilar objects, persons, or transactions with a uniform tax could result in discrimination. This principle underscores the importance of ensuring fairness and equality in taxation, acknowledging that varied economic realities necessitate exemptions and deductions to maintain equity. Therefore, these provisions are not only constitutionally valid but also crucial in meeting the evolving needs of society.

This discussion highlights the necessity of fair and equitable taxation. Exemptions and deductions are crucial to address diverse taxpayer circumstances and ensure that taxation remains fair and equitable. While these provisions must be interpreted strictly to prevent unjust benefits, they are essential in meeting the evolving needs of society. The principle of equality in taxation does not imply absolute uniformity but rather a fair classification that serves the purpose of the legislation and adheres to constitutional mandates.

Footnotes

1. Govind Saran Ganga Saran v. Commissioner of Sales Tax & Ors., 1985 (Supp) SCC 205.

2. Vikram Cement & Anr. v. State of Madhya Pradesh & Ors., (2015) 11 SCC 708; Kunnathat Thatehunni Moopil Nair v. State of Kerala & Anr., 1960 SCC OnLine SC 7.

3. (1969) 1 SCC 681

4. N.V. Somaraju v. Government of India & Ors., 1972 SCC OnLine AP 207.

5. Amalgamated Tea Estates Co. Ltd. v. State of Kerala, (1974) 4 SCC 415.

6. 2017 SCC OnLine Del 800303

7. (2015) 10 SCC 681

8. (1990) 4 SCC 366

9. 2019 SCC OnLine Del 6611.

10. Commr. of Customs v. Dilip Kumar & Co., (2018) 9 SCC 1.

11. 1968 SCC OnLine SC 122

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.