The following are the primary sources of national family law in Ukraine:

- the Constitution (1996);

- the Family Code (2002);

- the Civil Code (2003); and

- the Law on the Protection of Childhood (2001).

The Constitution has the highest legal force in the country and all laws and regulations must align with it. It establishes fundamental principles of family law, such as:

- the free consent of both a woman and a man in marriage;

- the equality of each spouse; and

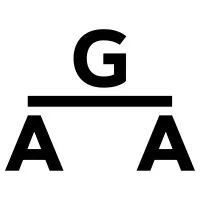

- the equal status of children regardless of their origin.

Ukraine operates under a civil law system. The primary source of civil law is the Civil Code, which is supplemented by the Family Code. The Ukrainian courts base their decisions on these codes, as no officially recognised doctrine or precedent exists. However, the Ukrainian courts must follow the legal conclusions made by the Supreme Court, particularly in family law cases.

The Family Code (2002) sets out provisions relating to:

- marriage and divorce;

- personal non-property and property rights;

- the duties of the married couple;

- the content of personal non-property and property rights; and

- the duties of:

-

- parents and children;

- foster parents; and

- adopted children and relatives.

International treaties – including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH) Children’s Conventions – are also considered part of the national family law framework.

Ukraine has officially ratified the following treaties:

- the UN Convention on the Nationality of Married Women (1957);

- the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989);

- the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (1980);

- the Hague Convention on Parental Responsibility and Protection of Children (1996);

- the Hague Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and Other Forms of Family Maintenance (2007); and

- the UN Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Relating Maintenance Obligations (1973).

International conventions (treaties) ratified by the Supreme Council of Ukraine form a substantial part of Ukrainian legislation and take precedence over national laws in case of conflict.

For example, the UN Convention on the Nationality of Married Women (1957) states that registration of marriages between citizens of a particular state and foreigners does not automatically change the wife’s citizenship. This rule is reflected in the Law on Citizenship (2001).

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the HCCH Children’s Conventions significantly influence Ukrainian law, particularly child protection and family law. Ukraine has implemented procedures to ensure:

- the prompt return of children who are wrongfully removed or retained across international borders;

- the recognition and enforcement of protective measures taken by other contracting states; and

- mechanisms for the international recovery of child support and family maintenance.

The Cabinet of Ministers (ie, the government) is the highest authority within the system of executive bodies. The government is responsible for:

- monitoring the execution of the Constitution of Ukraine and other legislative acts by executive authorities; and

- taking measures to address any shortcomings in their performance.

The Ministry of Justice oversees the legal system, ensuring that legislation is applied correctly and consistently.

The Ministry of Social Policy is responsible for developing and implementing state policies related to:

- child protection;

- social services; and

- family support.

The Service for Children’s Affairs:

- oversees the implementation of child protection policies;

- monitors child welfare; and

- coordinates efforts with other agencies.

Local child protection services provide direct support and services to children and families locally, implementing child protection measures and interventions.

UNICEF and other international organisations collaborate with Ukrainian authorities to:

- strengthen child protection systems;

- provide humanitarian aid; and

- support policy development.

The activities of all these bodies are guided by principles such as:

- the rule of law;

- legality;

- the separation of state powers;

- continuity;

- collegiality;

- joint responsibility;

- openness; and

- transparency.

Ukraine has ratified several bilateral and multilateral treaties with other countries that establish the procedures for recognising and enforcing foreign orders. The enforcement of these awards depends on the specific terms outlined in the agreements between Ukraine and the respective countries.

The Civil Procedural Code (2004) specifies the procedure for recognising and enforcing foreign court orders in Ukraine. An international court’s judgment can be enforced for three years from the date on which it became valid. An exception to this rule applies to periodic payments, which can be enforced and collected throughout the entire sanction period.

In the absence of international treaties between Ukraine and the relevant state, the principle of reciprocal enforcement of foreign court orders applies. According to Article 462 of the Civil Procedural Code, reciprocity is presumed to exist unless proven otherwise.

Generally, under Ukrainian law, the principle of reciprocity implies that if Ukrainian court orders are enforced in a particular foreign country, the court orders from that country will also be enforced in Ukraine.

The procedure includes applying to the local Ukrainian court with the respective application requesting recognition and enforcement of a relevant foreign judgment or order.

Generally, cases are heard in the relevant courts at the defendant’s residence.

According to Article 3 of the Law on Freedom of Movement and Free Choice of Place of Residence (2003), the notion of ‘residence’ refers to the administrative unit where an individual lives for more than six months each year. Ukrainian law mandates the registration of one’s place of residence.

Alimony, paternity recognition and divorce cases can also be filed in the courts at the claimant’s residence based on their preference (Article 28 of the Civil Procedural Code).

The registration of residence or a temporary address, or the lack of such registration, does not impact the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution, laws or international agreements in Ukraine.

Therefore, even if foreigners do not have a registered residence address in Ukraine, provided that they have lived in an administrative unit for over six months in a year, they are considered to reside there and can file a claim at that location.

The respective jurisdictional directions can be found in the respective bilateral and multinational instruments ratified by Ukraine, such as the Hague Convention on Parental Responsibility and Protection of Children (1996). The Law on International Private Law also provides guidance on jurisdictional issues where a dispute with a so-called ‘foreign element’ exists.

Foreign nationals involved in family disputes have procedural rights and duties equal to those of Ukrainian citizens.

When determining jurisdiction in disputes involving foreign elements, Ukrainian courts adhere to:

- the Civil Procedural Code; and

- the Law on International Private Law.

According to Article 75 of the Law on International Private Law, a Ukrainian court must refuse to initiate proceedings if a court or other jurisdictional authority in another country is already considering the same dispute involving the same parties, subject and grounds.

If a request to dismiss the proceedings is made after the court has begun hearing the case, the court will not consider it if another court is already handling a dispute between the same parties on the same grounds, leaving such a domestic case without consideration and returning it to the claimant.

Nevertheless, the Ukrainian courts have exclusive jurisdiction over cases involving:

- real estate located within Ukraine; or

- matters concerning relationships between parents and children where both parties reside in Ukraine.

Where both spouses are Ukrainian nationals living permanently abroad, they may file their divorce case before the Ukrainian court, regardless of their current residence, if they receive respective permission from the Supreme Court of Ukraine. Such permission can be obtained by preparing an additional application requesting the establishment of jurisdiction in Ukraine.

Under Article 21 of the Family Code, a ‘family’ is defined as a “union between a man and a woman who live together, have a joint household, and share mutual rights and duties”. As a result, same-sex spouses are not officially recognised in Ukraine.

However, according to Article 74, if a man and a woman cohabit as a family without being married to each other or anyone else, any property that they acquire is considered jointly owned unless they have a written agreement stating otherwise. Therefore, civil partnerships are partly regulated in Ukraine.

According to Article 74 of the Family Code, when a woman and a man live together as a family but are not married or in any other marriage, property acquired during cohabitation is owned jointly.

The fact of the cohabitation is to be established by the court. In case of success, property subject to joint ownership between an unmarried woman and man is subject to the same provisions that govern joint ownership between spouses.

Partners can depart from this ‘common joint property’ regime by agreement, re-designating present and future private personal and common joint property. Such agreement between the cohabitees is essentially the same as a marriage contract between spouses (pre-nuptial or nuptial agreements).

Under Article 91 of the Family Code, if a woman and a man who are not married have lived together as a family for a significant period and one of them becomes incapacitated while living together, that individual has the right to support similar to that of a spouse.

Additionally, Ukrainian law outlines the rights and obligations of both parties towards each other and any joint children if their cohabitation is established.

Ukrainian law does not explicitly recognise civil partnerships. However, one party from the cohabiting couple can formalise their relationship through the courts by demonstrating:

- their joint residence;

- a shared lifestyle; and

- mutual rights and obligations.

Generally, the court may recognise a relationship as marital and confirm rights to common ownership if a man and a woman:

- are not married to anyone else; and

- have established a longstanding relationship that resembles a typical spousal relationship.

Generally, the applicable law does not provide a possibility for mutual application to the court. If one of the cohabiting couples wants to establish and confirm factual marital relationships, he or she must file a respective application to the court.

Another way to establish such relationships is to conclude an agreement described in question 3.3.

Ukrainian law does not specify the length of cohabitation required to determine the existence of marital relations. Cohabitation need not have begun in Ukraine; however, it must have occurred in Ukraine for a sufficient period.

According to the Supreme Court’s case law, the court will evaluate the duration of cohabitation in each case. This evaluation may involve witness testimony and evidence of joint property acquisition when the couple lived together.

Evidence of cohabitation and a joint household can include various factors that are characteristic of family life, such as:

- living together as a couple in the same home;

- sharing meals;

- maintaining a joint budget;

- providing mutual care; and

- acquiring property for joint use.

According to the Family Code, marriage is a family union registered with the state authority between a woman and a man. Therefore, foreign civil partnerships and same-sex marriages are not currently recognised in Ukraine.

However, in 2023, the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) registered draft Law 9103 on the Institute of Registered Partnerships, which has not yet been adopted.

This draft law outlines the legal and organisational framework for registered partnerships, including:

- legal status;

- personal non-property rights;

- property rights;

- obligations of registered partners;

- the procedure for state registration; and

- the process for terminating registered partnerships.

According to this draft law, a ‘registered partnership’ is a voluntary family union between two adults, regardless of sex, that is registered according to the established procedure. This partnership is based on:

- mutual respect, understanding and support; and

- shared rights and obligations.

For a foreign marriage to be legally recognised in Ukraine, it must meet the validity requirements outlined in Article 58 of the Law on International Private Law. A marriage can be concluded between:

- two citizens of Ukraine;

- a citizen of Ukraine and a foreign national; or

- a citizen of Ukraine and a stateless person.

The following marriages, when concluded according to the laws of a foreign country, are also considered valid in Ukraine:

- between foreign nationals;

- between a foreign national and a stateless person; or

- between individuals without citizenship.

for the marriage to be valid in Ukraine, it must satisfy the validity requirements outlined in the Family Code, which include the following:

- Both parties must have reached the legal marriageable age;

- There must be free consent from both individuals; and

- The marriage must be monogamous.

The marriage should not be based on any grounds that would invalidate it under Ukrainian law. For example, relatives of the direct line of kinship cannot be married to each other.

Common law or de facto marriages are not recognised as valid marriages in Ukraine.

Religious and customary marriages are not forbidden in Ukraine. Parties are free to enter religious marriages.

However, these marriages are not legally recognised. To be considered legally married, couples should:

- register their marriage with the public civil registration authority; and

- obtain a state marriage certificate.

Chapter 8 of the Family Code sets out the regulations governing the default matrimonial property regime.

According to Article 60 of the Family Code, all property that spouses acquire during their marriage is considered common joint property, with exceptions specified by law. This means that the common joint property regime is the default status for spouses’ property.

In contrast, private personal property includes assets:

- acquired before the marriage;

- received before or during a marriage as gifts or through inheritance; or

- purchased with personal funds (Article 57 of the Family Code).

If private personal property generates income, fruits or breeds during the marriage, that will be treated as separate personal property.

However, if the increase in the value of one spouse’s private personal property results from the efforts or contributions of the other spouse, the court may classify that property as common joint property. In such cases, the other spouse has the legal right to a share in it.

If the parties wish to apply a different property regime, they should enter into a written agreement (eg, a pre-nuptial/post-nuptial agreement) before or during the marriage.

The parties are free to agree on their property arrangement. If they choose not to conclude such an agreement, the default regime of common joint property will automatically apply.

Ukrainian law recognises pre-nuptial agreements as valid and enforceable. Chapter 10 of the Family Code (2002) addresses them.

Generally, foreign separation of property and post-nuptial agreements are valid in Ukraine if they:

- are valid in their country of origin; and

- do not conflict with Ukrainian family law.

The requirements to formalise the agreement are basic. Both parties must visit a notary public and sign the paper document in the notary’s presence. If necessary, an agreement in Ukrainian and an official translation into the other language of any party can also be signed in front of the notary.

Couples can use a marriage agreement to:

- manage the distribution of property;

- determine or exclude the distribution of property from any cohabitation before marriage; and

- specify the applicable jurisdiction and law.

According to the Family Code, a marriage agreement can be established between:

- those who intend to register their marriage (engaged couples); and

- already married individuals.

If the agreement is concluded before registration of the marriage, it will take effect from the date of state registration.

However, a marriage agreement can be annulled at the request of one party through a court ruling or by mutual consent of both partners.

In Ukraine, a nuptial agreement may be contested in court if it leaves one spouse in an “extremely unfavourable material position” (Article 93 of the Family Code). In such cases, the court will consider whether the agreement has placed the spouse in a significantly worse financial position than they would have been under the default marital property regime.

The Ukrainian courts may need to apply conflict of laws principles to determine which jurisdiction’s laws are relevant, mainly when the agreement involves foreign elements. The domicile or habitual residence of the parties can influence which court has jurisdiction over the contract and any related disputes.

The location of real estate can significantly affect enforcement of the agreement. Assets in different countries may be subject to distinct legal frameworks, impacting how they are divided.

Therefore, if the parties have assets in multiple countries or plan to reside in different jurisdictions, it is particularly important to determine the applicable law and jurisdiction in the agreement. Ukrainian law allows the parties to specify the jurisdiction in their agreement.

Ensuring that the nuptial agreement will be recognised and enforceable in all relevant jurisdictions is also crucial. The parties’ plans, such as potential relocation or changes in domicile, should be considered when drafting the agreement. This will help to maintain the agreement’s relevance and enforceability, even as circumstances change.

Generally, the rules of the jurisdiction in which the real estate object is located will be applied to govern its property regime for the spouses.

Ukraine does not officially recognise same-sex marriages, making such marriage agreements invalid.

According to the Family Code, the parties can conclude a nuptial agreement (a marriage contract as per the official translation of the code). The current legal framework does not provide for other possible kinds of arrangements between the spouses, including a separation agreement.

There are no special rules for divorce proceedings between Ukrainian citizens (for more information, please see question 2.1).

When determining jurisdiction in disputes involving foreign elements, the Ukrainian courts adhere to:

- the Civil Procedural Code; and

- the Law on International Private Law.

In such cases, the Ukrainian courts have jurisdiction to handle divorce proceedings in the following circumstances:

- At least one of the spouses has a residence in Ukraine;

- The marriage was registered in Ukraine; or

- The couple have minor children who reside in Ukraine.

Generally, the Ukrainian jurisdiction applies the principle of freedom of marriage, which in turn leads to the principle that no one can be forced to stay in a marriage if they are unwilling to do so.

In Ukraine, two official authorities can dissolve a marriage:

- civil registry offices; and

- the local courts.

If both spouses are willing to separate and have no underaged children, a divorce before the civil registry offices is possible. It is unnecessary to state or prove any reasons for the divorce before the civil registry offices.

If a couple has underaged children, they can divorce in court.

If both spouses agree to the divorce, they must file a joint application and submit it to the court or the civil registry office along with the agreement certified by the notary regulating custody and child support issues. Again, during this procedure, it is not necessary to provide reasons for the divorce.

If one spouse believes that the marriage has broken down and reconciliation is impossible, they can file a statement of claim and specify the reasons, such as:

- different approaches to lifestyle;

- separate residence; or

- the inability to live together as one family.

Such reasons can be formally stated and there is no need to prove them specifically in court proceedings.

Lastly, a divorce can also be granted if a spouse is declared legally incapacitated or deceased. In such cases, a court decision declaring incapacity or a death certificate can be used as proof for the court.

The marriage is dissolved from the moment of registration of the divorce with the public civil registration authority. If the marriage is dissolved by court order, it is dissolved when the judicial decision enters into legal force.

The divorce process in Ukraine consists of several steps and can vary in duration based on the specific circumstances of each case. The court schedule also influences the timeline, but generally, it may take anywhere from several months to a year to complete.

If both spouses agree to the divorce and there are no minor children or disputes over property, they can file a joint application at the civil registry office. This is the simplest and quickest method and usually takes around one month after filing of a joint divorce application with the civil registry office to complete.

If minor children are in the marriage at the time of the separation, the spouses can file a joint petition to the court. Usually, it takes around one month to obtain a divorce from the date on which the court initiates the proceedings.

If one spouse does not consent to the divorce, the application must be filed in court by the other spouse.

The court may initiate a reconciliation process to help the spouses resolve their differences, although this step is not mandatory and the courts very seldom apply this process themselves.

The divorce process is considered finalised once the court decision has been issued and takes legal force. The decision takes legal force:

- after the expiry of a 30-day period; and

- if an appeal petition is not filed.

Therefore, in the case of a joint petition, it takes around two to three months to obtain a valid divorce decision. A contested divorce may take longer, affording the possibility for a reconciliation period if this is requested by one of the parties.

Divorce proceedings can be treated separately from other related matters. It is possible to file only for divorce in Ukraine.

It is possible to file for divorce before the civil registry offices.

The sole main restriction is the absence of minor children. The spouses may have adult children when submitting an application to the civil registry offices.

Applicants can apply for this service in person or through a legal representative.

The civil registry offices will issue a divorce certificate one month after the date of submission of the joint application date, provided that it has not been withdrawn by either spouse. Both applicants will receive a certificate documenting their divorce.

A foreign divorce decree must be legalised according to international agreements. Generally, the necessary documents include:

- the original divorce decree;

- an apostille or legalisation; and

- a certified translation into Ukrainian.

A foreign divorce must not violate Ukrainian public policy. For example, divorces involving same-sex marriages, which are not recognised in Ukraine, will not be valid.

Religious divorces also are not recognised by Ukrainian civil law. Only civil divorces have legal standing in Ukraine.

In Ukraine, a court may establish a separate residence regime for spouses if they are unable or unwilling to live together. This arrangement does not terminate their rights and obligations under the Family Code and their marriage contract. However:

- property acquired afterwards is not considered marital; and

- a child born more than 10 months after separation will not automatically be recognised as the husband’s child.

The regime can end if:

- the family relationship is renewed; or

- either spouse requests a court decision.

A marriage is considered invalid if:

- it is registered while one party is in another marriage;

- the spouses are direct relatives; or

- one spouse is declared incapable.

Invalidity can be established by the court if:

- the marriage was entered without free consent; or

- the marriage was fictitious (not intended to establish a family).

Other possible conditions for invalidity include marriages:

- between adoptive parents and their adopted children;

- between close relatives; or

- with individuals who:

-

- conceal serious illnesses; or

- are below the legal age for marriage.

In determining validity, the court will consider:

- the violation of rights;

- the duration of the cohabitation; and

- the nature of the relationship.

The right to claim invalidity is granted to either spouse and others whose rights are affected, such as parents or guardians.

An invalid marriage is recognised from the date of registration and does not create spousal rights or obligations. However:

- property acquired during the marriage is treated as jointly owned; and

- parental rights for any children remain unaffected.

Divorce papers must be delivered directly to the recipient. The other party in the case can be notified by post or courier service.

If the recipient is unavailable, the papers can be:

- left with an adult family member at the recipient’s residence; or

- delivered to an authorised representative at the recipient’s place of work.

The recipient must sign an acknowledgement of receipt. If the papers are left with a family member or representative, they must also sign an acknowledgement.

If the recipient resides abroad, the documents can be served under the provisions of the applicable international treaties, such as the Hague Conference on Private International Law Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil and Commercial Matters 1965 (‘Hague Service Convention’).

If the country in which the recipient resides is a party to the Hague Service Convention, the process is simplified. The papers are sent to the central authority in that country, which then arranges service.

If the recipient resides in a country that is not a party to the Hague Service Convention, service can be effected through diplomatic channels through a formal request from a court in Ukraine to a court in a foreign country.

The court has several significant powers that facilitate the judicial process while upholding the principles of objectivity and impartiality. One of its primary roles is to oversee the process of a case from start to finish. During hearings, the court thoroughly examines evidence related to the financial status of both parties, which encompasses various aspects, such as:

- income;

- assets;

- debts; and

- overall financial liabilities.

This information is crucial to ensure a fair evaluation of the case.

However, with the parties’ consent, a dispute may be settled before the start of court hearings with the participation of a judge.

During joint meetings, the judge plays an active role by clarifying:

- the legal grounds for the claim; and

- any objections that may arise.

This involves a thorough explanation the evidence required for the case, tailored to the specific nature of the dispute. The judge will encourage both parties to discuss their perspectives and explore various avenues for peaceful resolution.

Furthermore, the judge may propose solutions or compromises that could lead to an amicable settlement.

Nevertheless, this procedure is not common in Ukraine, despite having its legal basis in a direct mention in the local civil procedural rules.

(a) What orders can the court make in relation to spousal and child maintenance on divorce or judicial separation and how are the relevant amounts calculated?

The courts may issue orders for spousal maintenance and child support in Ukraine during divorce or judicial separation proceedings. However, such disputes are typically decided separately from divorce proceedings.

The court itself will not award financial support if the claimant has not expressly requested this in their statement of claim.

Spousal maintenance is typically awarded to a spouse who is incapable or severely lacking in sufficient means to support themselves. The court will consider both spouses’ income and assets, including:

- salaries;

- investments;

- property; and

- other financial resources.

Child maintenance is intended to support:

- minor children (under 18 years old); or

- adult children who cannot support themselves due to ongoing education or disability.

The court will assess the child’s basic needs, including:

- food;

- clothing;

- education;

- healthcare; and

- other essential expenses.

It will also consider the income of both parents, which encompasses:

- salaries;

- bonuses; and

- other sources of income.

Any special needs of the child, such as medical or educational requirements, are also factored into the calculation.

Maintenance may be imposed by a court order and may be:

- a certain percentage of the total net income; and/or

- a fixed sum of money.

Alimony must be paid monthly.

(b) What general principles apply to spousal and child maintenance? What specific factors will the court consider in deciding which orders to make in this regard?

Under Article 75 of the Family Code, a former spouse may be required to provide financial support if one spouse:

- becomes disabled during the marriage or within one year of the divorce;

- is pregnant;

- cares for a child under three or a disabled child; or

- is expected to reach pension age within five years.

Where two people who are not married have lived together as a family, the incapacitated partner can also claim maintenance.

A person can also seek financial assistance after divorce if they become disabled within a year of the divorce, provided that the ex-spouse can afford to help. Even if a disability arises more than a year after the divorce due to the other spouse’s wrongful actions, support may still be granted.

If one spouse is unable to pursue education or work due to family responsibilities or other significant factors, they are entitled to maintenance for up to three years post-divorce, even if they are capable of working.

The courts will consider various factors when determining maintenance, such as:

- the child’s health and financial situation;

- the financial status of the alimony payer;

- support from other family members;

- the need to support a legally incapable spouse or children from a new marriage; and

- property ownership and documented expenses.

Alimony must be at least 50% of the minimum living wage for a child, which is updated annually and adjusted quarterly.

(c) When do spousal and child maintenance expire?

Generally, parents are obliged to support their children until they reach the age of majority.

If an adult son or daughter continues their education and requires financial assistance, parents must provide support until the child turns 23, if they can do so. The right to maintenance ends if the child ceases their education.

Spousal maintenance in Ukraine can be granted for a fixed term or on an open-ended basis, depending on the specific circumstances and the provisions outlined in Chapter 9 of the Family Code.

As a rule, one spouse’s right to maintenance after the divorce is terminated if that individual:

- regains the ability to work; or

- enters into a second marriage.

The spouse with whom the child lives has the right to maintenance until the child reaches the age of three. If a child has physical or mental disabilities, the spouse with whom the child lives has the right to maintenance until the child reaches the age of six.

(d) What happens to spousal and child maintenance after the death of the paying party or if the paying party is an adjudicated bankrupt?

The obligation of the alimony payer to continue making payments ceases upon their death, as this financial responsibility is intrinsically linked to the individual and cannot be transferred to or fulfilled by another party.

However, their heirs are obliged to settle any outstanding alimony arrears due at the payer’s death. This obligation is fulfilled from the assets available within the deceased’s hereditary estate, including property, savings or other valuables left behind.

Once insolvency proceedings have been initiated against an individual, a legal moratorium temporarily halts the recovery of amounts from the debtor under enforcement documents.

Despite this general rule, this moratorium does not extend to alimony obligations. Payments designated as alimony are still enforceable and can continue to be collected, ensuring that the financial needs of the dependent beneficiaries are met irrespective of the payer’s insolvency status.

(e) Which bodies are responsible for issuing child support orders in your jurisdiction?

Parents can voluntarily agree on the payment of alimony. Such agreement must be notarised.

If it is impossible to reach agreement between the parents, the funds for the child’s maintenance can be recovered by a court decision.

The state enforcement service or a private enforcement officer can enforce court decisions on collecting alimony. The debts arising from alimony agreements can be collected:

- based on the enforcement note of the notary; or

- during separate court proceedings.

The respective decision can again be enforced by the authorities mentioned above.

(f) Does the child support regime vary depending on whether the parents’ relationship was formalised (eg, marriage/civil partnership/co-habitation)?

According to the Family Code, children have equal rights and responsibilities concerning their parents, regardless of the marital status of those parents. This means that, irrespective of whether the parents were married, divorced or never married, the children are entitled to the same level of care and support.

(g) Can a child (adult or minor) make a direct claim for child support? If so, under what circumstances?

A minor child (under 18 years old) cannot file a claim directly. Instead, a parent or legal guardian must file the claim on the child’s behalf.

Adult children (over 18 years old) who are still pursuing their education, such as attending university, can file a claim for child support directly if they are unable to support themselves.

(h) What specific considerations and concerns should be borne in mind in relation to child support where the parties have international connections?

It is essential to establish which country’s courts have jurisdiction over child support and which law will be applied, because the legal regulation of child support varies from country to country (in some countries, it may be less favourable to the child).

The jurisdiction and applicable rule may depend on factors such as:

- the child’s habitual residence;

- the parents’ location; and

- existing agreements between the participating countries.

The next problem may be enforcement of the court decision. Many countries, including Ukraine, are parties to the Hague Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and Other Forms of Family Maintenance (2007). This convention facilitates the recognition and enforcement of child support orders across borders. However, some countries have bilateral agreements that provide mechanisms for enforcing child support orders, so it is also essential to understand this.

Enforcing child support orders across international borders can cause problems such as:

- differences in legal systems;

- language barriers; and

- the need to translate documents.

At the same time, states that are parties to international treaties often have mechanisms for mutually enforcing decisions on the recovery of alimony. This means that an order to recover alimony issued in one country can be enforced in another.

(i) What are the main enforcement methods to ensure compliance with child support awards? What are the typical consequences of breach?

If a debt is caused by the fault of the person obliged to pay alimony (as determined by an agreement between the parents), the recipient has the right to collect a penalty that cannot exceed 100% of the debt.

The court may reduce the amount of this penalty, considering the alimony payer’s financial and family circumstances.

If there are alimony arrears which in aggregate exceed the amount of the respective payments for four months, the state enforcement officer will issue a reasoned resolution until the alimony debt is paid in full establishing:

- a temporary restriction on the debtor’s right to travel outside Ukraine;

- a temporary restriction on the debtor’s right to drive vehicles;

- a temporary restriction on the debtor’s right to use firearms for hunting, pneumatic or cooled weapons, and domestic devices for firing cartridges equipped with rubber or similar non-lethal projectiles; or

- a temporary restriction on the debtor’s hunting rights.

If alimony is paid to maintain a child with a disability or a child who is suffering from severe health system disorders, the state enforcement officer will issue the resolutions referred to above if there are child support arrears which in aggregate exceed the amount of the relevant payments for three months.

(a) What orders can the court make in relation to the division of assets on divorce or judicial separation?

The court typically divides joint property equally between spouses. Joint property includes assets acquired during the marriage, regardless of whose name is on the title or who paid for them.

The court may assign specific real estate to one spouse while the other spouse receives compensation or assets of equivalent value. This also applies to vehicles, furniture and other personal belongings, with adjustments to ensure a fair division.

Compensation can be awarded to one of the spouses instead of their share of property only with their consent.

The court may require a valuation and division of business interests if the spouses own a business.

If the spouses have a valid nuptial agreement, the court will consider its terms when dividing assets.

(b) What general principles apply to the division of assets? What specific factors will the court consider in deciding which orders to make in this regard?

When dividing marital property, it is generally accepted that the husband and wife’s shares are equal. However, this equal division can be adjusted based on specific agreements:

- made between the spouses; or

- outlined in a formal marriage contract.

The court’s primary objective during this division process is to ensure a fair allocation of assets, which considers the contributions and needs of both parties involved. Importantly, this does not always equate to a strict 50-50 split.

The court will evaluate each spouse’s financial and non-financial contributions throughout the marriage. ‘Financial contributions’ include the income earned by each partner and any assets acquired during the marriage, such as:

- savings;

- investments; and

- real property.

‘Non-financial contributions’ can include managing household duties and childcare.

The court prioritises the welfare of minor children when making its decision. The share of the wife or husband’s property can be increased if children live with them, provided that the amount of alimony they receive is insufficient to cover the children’s physical and spiritual development and treatment.

Beyond just the children’s needs, the court will also carefully examine each spouse’s circumstances, such as:

- earning potential;

- career prospects; and

- any financial hardships that they may face post-separation.

This holistic approach ensures that the court’s division of property:

- is equitable; and

- adequately reflects:

-

- the diverse contributions and needs of both spouses; and

- the paramount importance of the children’s welfare.

(c) How does the court treat unreasonable conduct during the marriage in relation to financial matters (eg, reckless spending, gambling, dissipation of assets) when determining on capital division in divorce?

According to the Family Code, when resolving a dispute on the division of property, the court may deviate from the principle of equality of the spouses’ shares in significant circumstances – in particular, if one of them:

- did not take care of the material support of the family;

- evaded participation in the maintenance of the children;

- hid, destroyed or damaged the joint property; or

- spent the joint property to the detriment of the interests of the family.

(d) Is it common for expert evidence to be adduced and used in court (eg, forensic accountants, valuations of companies/properties)?

Expertise is used to determine the market value of specific assets or property complexes that must be divided. These may include assets such as:

- real estate;

- vehicles;

- businesses;

- financial accounts; and

- art objects.

Examinations are conducted to identify the specific assets eligible for division. This process may also assess the feasibility of dividing properties such as:

- real estate;

- vehicles; and

- businesses.

Once the evaluation is complete, an expert report detailing the results and methodologies will be prepared. This report serves as evidence in court.

In some cases, an appraiser may be called as a witness during a court hearing to:

- explain their findings; and

- answer questions from the parties involved or the court.

(e) Is the family home treated differently compared to other family assets on divorce or judicial separation? If so, how?

While the family home is subject to equitable distribution like other marital assets, the court may consider the needs of the custodial parent and children. This could result in one spouse being awarded the home to maintain continuity for living there with the children.

In that case, the court may assign this real estate property to one spouse while the other spouse receives compensation or assets of equivalent value.

(f) Are trusts recognised in your jurisdiction? How are they treated on divorce or judicial separation?

In 2019, the Civil Code introduced trust ownership as a new security instrument. This allows property to be transferred to a trustee to secure obligations under a loan agreement.

However, the official legal trust structure is still not recognised in Ukraine and is thus not regulated by the law. Thus, Ukrainian law does not explicitly address the treatment of trusts regarding divorce or judicial separation.

(g) What are the main enforcement methods to ensure compliance with financial orders issued on divorce or judicial separation? What are the typical consequences of breach?

The state enforcement service or a private enforcement officer enforces decisions on the division of marital property.

In addition, the courts can provide interim relief that guarantees the execution of a court decision where claims are satisfied. Such an order can, for example:

- temporarily seize the other spouse’s accounts; or

- prohibit the alienation of real estate.

Again, it is made by the state enforcement service or a private enforcement officer.

Enforcement measures may include:

- the enforcement of:

-

- funds;

- securities;

- other property (property rights);

- corporate rights;

- IP rights;

- objects of scholarly or creative activity; and

- other property (property rights) of the debtor, including where:

-

- it is in the possession of other persons or belongs to the debtor from different persons; or

- the debtor owns it jointly with other persons; and

- seizure from the debtor and transfer to the collector of the items specified in the decision.

Non-compliance with financial orders can result in the imposition of penalties and fines by the court. In case of the debtor’s repeated failure to comply with the decision without valid reasons, the executor will:

- impose a double fine on the debtor; and

- apply to the pre-trial investigation authorities with notice of the commission of a criminal offence.

(h) If the parties are in agreement on financial matters, is non-judicial resolution of these possible? What requirements and restrictions apply in this regard and how does the process typically unfold?

If the spouses are willing to resolve their property issues amicably, they can enter into a property division agreement. However, while the marriage contract regulates property relations between the spouses, it is forbidden to distribute assets that are subject to state registration in such a contract.

Therefore, if spouses consider the division of the real estate objects, they will need to enter into a property division agreement.

Such an agreement may distribute all kinds of joint assets between the spouses or former couple, including real estate. It must be:

- concluded in written form; and

- certified by a notary.

After certification of the agreement, the notary will respectively make new entries in the real estate register.

(i) Can the courts make financial orders in relation to a foreign divorce? What requirements and restrictions apply in this regard and who can apply for such orders?

The Ukrainian court must have jurisdiction over the matter. This typically applies if:

- one of the spouses resides in Ukraine; or

- the property in question is located in Ukraine.

The divorce procedure in Ukraine does not involve the settlement of financial issues between the spouses. The spouses can divide their joint property amicably or in court, even while still in the marriage. This division can also be done after the marriage, subject to the statute of limitations.

The limitation period does not apply to claims for the division of property that is the subject of the right of joint marital ownership unless the marriage between the parties has been dissolved. A three-year limitation period applies to a claim for the division of property filed after the divorce. The limitation period starts to run from the date on which one of the co-owners learned or could have learned of the violation of their property right.

The main guiding principle for custody and access arrangements is the child’s best interests. Both parents hold equal rights and responsibilities towards their children, irrespective of their marital status.

The Supreme Court has noted in its rulings that when making decisions, the courts must consider a number of circumstances – in particular:

- the parents’ attitude towards the fulfilment of their parental duties;

- the child’s personal attachment to each parent;

- the age of the child and their state of health;

- the child’s stable social ties;

- the child’s place of study;

- the child’s psychological state;

- the child’s desire to live with one of the parents;

- the personal qualities of each parent;

- the relationship between each parent and the child (eg, how they fulfil their parental duties concerning the child, how the child’s interests are taken into account and whether there is mutual understanding between each parent and the child);

- the possibility of creating conditions for the child’s upbringing and development; and

- a safe environment for the child’s life.

The Family Code guarantees that all children have the same rights and protections, irrespective of their parents’ marital status. According to the code, the paternity of children born out of wedlock must be established, ensuring that they receive the same legal recognition and rights as legitimate children.

Both legitimate and illegitimate children are entitled to care, support and parenting from both parents. Children born out of wedlock have the same inheritance rights as those born to married parents.

Therefore, regardless of marital status, both parents share equal rights and responsibilities towards their children. These include rights to:

- custody;

- access; and

- decision-making related to the child’s upbringing.

Currently, Ukraine does not recognise same-sex marriages or civil unions. Consequently, same-sex couples do not enjoy the same legal rights regarding children as married couples. However, individual members of same-sex couples can acquire parental rights if they are the biological or adoptive parent of the child.

The court has several significant powers that facilitate the judicial process while upholding the principles of objectivity and impartiality. However, with the parties’ consent, a dispute may be settled before the start of court hearings with the participation of a judge (please see question 7.1).

In child-related cases in the Ukrainian legal system, the courts can render various decisions to safeguard the child’s best interests. The court can:

- determine the child’s place of residence with one of the parents;

- define or adjust parental rights and responsibilities; and

- establish the amount and terms of child support payments.

In severe cases of parental neglect or abuse, the courts can deprive parents of their parental rights.

Generally, the Ukrainian court system is moving towards facilitating settlement in child matters, with an increased emphasis on alternative dispute resolution, particularly mediation. The courts also work with child welfare services to better understand the child’s situation and resolve conflicts.

The parties can also enter into a peaceful agreement at any stage of the court proceedings. The judge will then proceed with fixing reached by the parties’ arrangements in its court ruling. Such a court document has the legal power of a court decision.

As a rule:

- the child will be interviewed by representatives of the Service for Children’s Affairs; and

- the parents’ living conditions will be examined as one of the compulsory parts of the custody proceedings.

Thereafter, the custody and guardianship authorities will prepare a conclusion for the court on how the dispute between the parents should be decided.

The Service for Children’s Affairs may refer the parents to the City Children’s Centre, where qualified psychologists can meet with them and the children and provide appropriate assistance to the children.

The judge or parties may also seek so-called ‘court psychological expertise’ in relation to all related parties, including the children. The children can also be interviewed by a psychologist:

- engaged by the Service for Children’s Affairs with the help of state bodies and specialised centres; or

- at the request of one of the parents.

In case of a conflict between the parents, a psychologist is frequently involved in working with the children to minimise the negative impact on their psycho-emotional state. Often, the results of the psychologist’s work are submitted to the court as written evidence.

Under Ukrainian law, before the war, citizens under 16:

- could only travel outside Ukraine with the consent of their parents or guardians; and

- had to be accompanied by:

-

- their parents or guardians; or

- other authorised persons.

In the absence of both parents’ consent, travel is permitted with the notarised consent of the other parent.

There are some exceptions, as follows:

- The other parent is a foreign national or stateless;

- The child’s passport shows evidence of permanent residence abroad; or

- A court order on one of the following has been issued:

-

- termination of parental rights;

- recognition of the other parent as ‘disappeared missing’;

- recognition of the other parent as incapable; or

- permission to travel abroad.

The court usually:

- assesses the risk of wrongful removal or retention of the child; and

- determines the trip’s place, purpose and duration.

However, the child’s best interests are the primary consideration and outweigh parental interests in such cases. Children capable of forming their own views have the right to express themselves freely and their opinions will be considered based on their age and maturity.

The above rules apply only to children who are citizens of Ukraine. If a child has foreign citizenship and travels under foreign travel documents, they can freely enter and leave Ukraine with one of their parents.

Because of the war in Ukraine, one parent no longer needs to obtain notarised consent to cross the border. This rule has been valid since March 2022, when it was first introduced to ensure the safety of Ukrainian children.

Ukraine has adopted the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction in 2006, establishing a legal framework for addressing cases of wrongful child removal or retention.

Cabinet of Ministers Decree 952/2006 governs the implementation of the Hague Convention in Ukraine. This decree outlines the procedures and documentation necessary for applications seeking a child’s return or access.

The Ministry of Justice is the central authority for such matters. Upon receiving a return application, the Ministry of Justice will first attempt to facilitate a voluntary return through parental agreement.

If this fails, the ministry may initiate court proceedings on behalf of the applicant. Alternatively, the parents may directly pursue court action for the child’s return under Article 29 of the Hague Convention, bypassing the ministry.

While the Ministry of Justice provides basic legal assistance and services free of charge, court representation is only free for citizens of countries that offer reciprocal services to Ukrainian citizens. Therefore, individuals are recommended to retain legal counsel to represent their interests in court effectively.

In Ukraine, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), including surrogacy, are legally recognised and governed by:

- the Family Code;

- Ministry of Health Order 787/2013 on the Approval of the Procedure of Assisted Reproductive Technologies Appliance in Ukraine;

- the Rules of Registration of Civil Status Acts in Ukraine (Ministry of Justice, 18 October 2000);

- the Law on Fundamentals of the Legislation of Ukraine on Health Care (19 November 1992); and

- the Civil Code.

Surrogacy is exclusively available to legally married heterosexual couples who can provide documentary proof of their marriage. Same-sex couples and single individuals are ineligible.

A comprehensive surrogacy agreement is essential to clearly define all parties’ rights, responsibilities and expectations (see further question 9.2).

Surrogacy arrangements in Ukraine are formalised through a surrogacy agreement, which serves as the parties’ consent. This agreement can be:

- bilateral (intended parents and surrogate); or

- trilateral (including the medical institution).

Ministry of Health Order 7872013 on the Approval of the Procedure of Assisted Reproductive Technologies Appliance in Ukraine provides that the documents required for intended parents seeking ARTs are:

- a patient statement for ART use;

- copies of their passports;

- copies of their marriage certificate; and

- a notarised joint agreement (surrogacy agreement).

The surrogacy agreement must precede embryo conception and transfer. Agreements made post-conception risk invalidation as child transfer agreements because a person cannot be the subject of a contract.

Ukrainian law mandates a notarised, written surrogacy agreement before embryo transfer. Consequently, a notary must sign the surrogacy agreement in writing before the embryo transfer.

While the agreement’s form and specific terms are left to the parties’ discretion, its content must align with:

- the Civil Code;

- the Family Code; and

- other Ukrainian laws.

The key requirements for a valid surrogacy agreement include the following:

- Only legally married heterosexual couples can enter into such agreements.

- The surrogate must be an adult, capable woman with a healthy child, freely consenting and medically fit.

- The payment terms must avoid language suggesting child transfer or relinquishment of parental rights.

- Permissible payments include:

-

- compensation for pregnancy and childbirth services; and

- related expenses (eg, medical, living expenses, lost wages).

According to Part 2 of Article 123 of the Family Code, if embryos created via reproductive technology are transferred into the body of another woman, the contracting couple will be the parents of the child.

Therefore, the surrogate mother has no parental rights over the child. The intended parents will be recognised as the legal parents from the moment of conception.

Adoption in Ukraine is governed by:

- Articles 207–242 of the Family Code; and

- Cabinet of Ministers Decree 905/2008.

Key requirements for adoption include the following:

- It requires a court order.

- Adopters must be capable individuals aged 21 or older, unless they are relatives of the child.

- Adopters must be at least 15 years older than the child (18 years for adult adoptions).

- Married couples can adopt jointly. The legislation also establishes the possibility of one spouse adopting a child if the other spouse does not want to become an adoptive parent. One spouse should obtain the other’s notarised consent. In such cases, the other spouse only agrees to the adoption and does not acquire:

-

- the adoptive parent’s legal status; or

- the adopter’s rights and obligations.

- Unmarried cohabiting individuals may adopt with court approval.

- Single individuals may adopt if the child has only one legal parent, who will lose parental rights.

There is no limit to the number of children that an individual can adopt.

Foreign citizens can adopt if:

- they are a married couple; or

- one of them is a relative of the child.

International adoption has ceased due to the war in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian government is actively modernising its adoption processes. This includes a push for complete digitalisation to streamline procedures through the ‘Diia’ Unified State Web Portal of Electronic Services. Additionally, the Unified Information and Analytical System ‘Children’, which manages data on orphans and prospective adoptive families, is undergoing significant modifications to enhance its efficiency.

Ukrainian law permits joint adoption by married spouses. Single individuals are also eligible to adopt, regardless of sexual orientation. However, joint adoption by same-sex couples is not allowed.

There are two main forms of ADR procedures in Ukraine: mediation and arbitration.

However, the use of arbitration in family disputes is limited. Ukrainian law prohibits arbitration for disputes involving:

- immovable property;

- non-resident parties; and

- most family relationships (except those arising from marriage contracts).

Mediation received formal legal recognition in November 2021, with the enactment of the Law on Mediation. Although this law is relatively new, many mediation centres have already been established to help facilitate dispute resolution.

Mediation applies to various disputes – including civil, family, labour, economic, administrative and certain criminal and administrative disputes – focusing on fostering reconciliation.

Mediation can take place before or during legal proceedings, including during:

- pre-trial investigations;

- court cases;

- arbitration; and

- even the enforcement of court or arbitration decisions.

Mediation is conducted based on the parties’ mutual agreement and adheres to the principles of:

- voluntariness;

- confidentiality;

- mediator neutrality and impartiality;

- party self-determination; and

- equality.

To be enforceable and binding, any agreement reached by the parties during mediation or arbitration must satisfy both the specific and general requirements outlined in the Family Code and the Civil Code. These codes provide essential guidelines that govern the validity of agreements, particularly those concerning family law matters.

The scope for arbitration in family disputes is quite restricted. Consequently, it is imperative to engage mediators with specialised training in family law and ADR. This expertise is especially crucial in cases involving children, where sensitive issues surrounding custody, support and welfare are at stake.

Furthermore, arbitration:

- can only be utilised for disputes arising from a marriage agreement where both parties are residents of Ukraine; and

- exclusively applies to issues that do not involve immovable property.

This limitation underscores the need for clarity in the types of disputes that are eligible for arbitration under Ukrainian law.

On the other hand, mediation is precluded in situations where conflicts may impact the rights and legitimate interests of third parties who are not directly involved in the mediation process. This provision aims to protect the rights of individuals outside the mediation agreement, ensuring that their interests are not negatively affected by the outcomes of the mediation discussions. For example, creditors may have claims against shared assets in marital property division cases. Mediation agreements that unfairly distribute assets or debts could harm their interests.

Understanding which country’s courts have jurisdiction over a dispute is a critical first step in the legal process. Jurisdiction determines where a case can be heard and which legal framework will apply. Even if a Ukrainian court is considered to have jurisdiction, the complexity increases when determining which nation’s laws will apply to the specific case.

Therefore, incorporating a jurisdiction clause in legal agreements can provide clarity and benefits because you can choose the applicable law. It becomes even more important when the dispute involves foreign parties.

When dealing with assets spread across multiple countries, locating and valuing these assets can quickly become both complicated and expensive. This complexity is exacerbated in situations involving the cross-border enforcement of child support or spousal support orders. Each country may have its own legal procedures and navigating these can be fraught with challenges, including potential delays and variations in enforcement.

Accurate translation of documents is imperative, as even subtle nuances in language can lead to significant misunderstandings. Likewise, having skilled interpreters during court proceedings or mediation sessions is vital for effective communication.

A person can contact the National Police of Ukraine by:

- calling 102; or

- applying personally to the nearest department.

If a person has been subjected to physical violence, they additionally have the right to apply to a medical institution for emergency care. If the relevant case of domestic violence is qualified as a crime, the investigator or prosecutor must issue a referral to the victim for a forensic medical examination to establish the fact of bodily harm at the Bureau of Forensic Medical Examinations.

The court is authorised to issue restraining orders, the purpose of which is to protect the victim from the continuation of domestic violence.

An application for the issuance of a restraining order can be submitted by a person who has suffered from domestic violence or their representative. An application for the issuance of a restraining order should be applied to the local general court at the place of residence of the injured person.

Restrictive measures include:

- a prohibition on staying in the place of joint residence;

- the removal of obstacles in the use of property that is the object of the right of joint common ownership or personal private property of the injured person;

- restriction of communication with the affected child;

- a prohibition on approaching areas that the victim often visits; and

- a prohibition on searching for the victim, personally or through third parties, and communicating with them in any way.

The Law on Preventing and Combating Domestic Violence (2017) clearly defines ‘domestic violence’ as acts committed not only in the family but also:

- within the place of residence;

- between relatives;

- between former or current spouses; or

- between other persons who live (or lived) together as one family but are not (or have not been) in family relations or marriage with each other.

The law provides for several protection measures in case of domestic violence, including:

- the issuance of an urgent restraining order;

- referral to a programme for offenders; and

- criminal liability.

A restraining order may be issued for one to six months and extended for up to six months after the expiration of the period specified in the court decision on its issuance. To extend the restraining order, you should apply to the court with an application in the same manner as for its issuance.

These measures apply to all victims of domestic violence. Therefore, the absence of marriage is no obstacle to obtaining protection.

The court must notify the National Police of Ukraine about the issuance or extension of a restraining order no later than the day after a decision has been made to place the individual to whom the restraining order has been issued or extended under preventive registration. This notification should also be sent to the district and state administrations and the executive bodies of village, township, city, and city councils in cities at the applicant’s place of residence.

Authorised units of the National Police of Ukraine are responsible for monitoring the enforcement of special measures aimed at combating domestic violence by offenders during the validity of these measures.

If the offender violates these instructions, they will face liability, including criminal liability.

According to the Code of Civil Procedure, the court must consider a restraining order application within 72 hours of receipt.

The Service for Children’s Affairs will undertake the temporary placement of a child where there are signs of violence or abuse after providing the necessary medical care, medical examination or treatment. At the same time, it will consider the need to take away the child or deprive them of parental rights if the offenders are either or both parents (or adoptive parents).

According to Article 164 of the Family Code, the court may deprive a mother or father of parental rights if they cruelly mistreat the child, including through:

- any form of physical, psychological, sexual or economic violence, including domestic violence; or

- any unlawful transaction against the child, including recruitment, transfer, hiding, transfer or receipt of the child, committed to exploit the child using deception, blackmail or the child’s vulnerable state (Article 1 of the Law on Childhood Protection (2001)).

Therefore, while the term ‘ward of court’ might not be directly equivalent, Ukrainian courts have the authority to take necessary actions to safeguard a child’s welfare.

Current trends in the development of family law in Ukraine focus on several key areas, as follows.

Protecting children’s rights: Considerable emphasis has been placed on strengthening measures to protect children’s rights, including:

- preventing domestic violence; and

- ensuring that children have the right to grow up in a family environment.

In 2024, Ukraine adopted the Strategy for Ensuring the Right of Every Child to Grow in a Family Environment for 2024–2028. It considers the challenges posed by the war and aims to ensure the safe development of children within families. Therefore, the provision of individual support to families in difficult life circumstances should prevail. The strategy promotes the development of family-based forms of upbringing – such as foster care, family-type orphanages and adoption – rather than keeping children in institutional facilities.

Digitalisation of processes: The implementation of information and communication technologies is simplifying various legal procedures. For instance, Ukrainian citizens can now marry through the digital ‘Diia’ platform.

European integration: Ukraine is working towards harmonising its national legislation with European standards. This includes adapting legal norms to meet EU requirements and embrace European values and human rights, such as introducing civil partnerships and same-sex marriages.

In 2023, the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) registered Draft Law 9103 on the Institute of Registered Partnerships.

- Consider involving a professional mediator to facilitate discussions and help to resolve conflicts amicably.

- Attempt to settle all contentious issues through contractual agreements, such as marriage and alimony agreements, to minimise the need for court proceedings in the future.

- Ensure that all necessary documents are prepared and filed correctly to avoid delays and complications during divorce.

- Prioritise the best interests of the children involved. Ensure that custody and support arrangements are fair and consider the children’s emotional wellbeing. The lack of a clear co-parenting plan can result in confusion and instability for the children.

- Obtain legal advice to understand your rights and obligations. A lawyer can assist you in navigating the legal aspects of separation or divorce. Failure to seek legal counsel may result in overlooking important legal elements, leading to complications and potentially unfavourable outcomes.