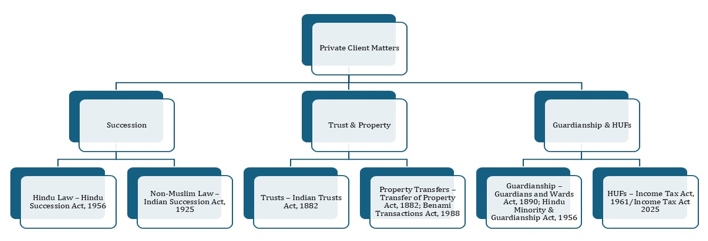

The legal framework governing succession and property in India is primarily outlined in several key laws. The Hindu Succession Act, 1956 applies to Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs. Intestate succession is dealt with in Sections 6–15 and 18–22, which specify the order and manner of devolution; while Section 14 confirms female ownership. Testamentary succession is addressed in Chapter III(30) of the same act. The Indian Succession Act, 1925 governs intestate and testamentary succession for Christians, Parsis, Jews and other non-Muslims, with:

- Part II covering intestate succession; and

- Part VI detailing wills, including:

-

- Sections 5–6 on domicile; and

- Section 63 on formalities for wills.

The Indian Trusts Act, 1882 regulates private trusts concerning duties, creation and beneficiaries without a statutory register. Property transfers are governed by the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 and the Benami Transactions Act, 1988, which oversee sales, gifts, mortgages and benami (ie, transactions where property is held by one person but the consideration has been paid by another, typically to conceal the identity of the real owner) dealings. Additionally, tax implications related to trusts and Hindu undivided families (HUFs) are addressed under the Income Tax Act, 1961 (ITA).

Additionally, matters concerning guardianship and minority are governed by the Guardians and Wards Act, 1890 and specific provisions within personal laws such as the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, which address the custody, property and welfare of minors.

Indian succession and property laws for non-residents, including non-resident Indians (NRIs), and foreign nationals are governed by a dual framework comprising personal laws and the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (FEMA), along with a range of regulatory guidelines.

For NRIs, succession is determined by the personal laws applicable to the deceased, such as:

- the Hindu Succession Act, 1956;

- the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937; or

- the Indian Succession Act, 1925.

Wills executed by NRIs are legally valid for Indian assets, provided that they adhere to the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which requires the will to be signed by the testator in the presence of at least two witnesses. While registration is not mandatory, it is recommended; and a formal probate process is required for wills in certain jurisdictions, including Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata.

The repatriation of funds from inherited assets is a capital account transaction strictly regulated under FEMA and Reserve Bank of India (RBI) guidelines. The movement of such funds from India is generally subject to an annual limit of $1 million per financial year, with the repatriation of amounts exceeding this cap requiring prior RBI approval. A critical restriction applies to inherited agricultural land plantation property and farmhouses: the proceeds from the sale of such property are not permitted to be repatriated.

For foreign nationals, the acquisition of immovable property is generally prohibited unless acquired through inheritance from a person who was a resident of India. Under the Indian Succession Act, 1925, the distribution of an estate is governed by the principles of domicile and situs. Succession to movable assets is determined by the law of the deceased’s country of domicile, whereas succession to immovable property is governed by the law of its physical location (situs).

While India does not impose inheritance or estate tax, any income derived from inherited assets, such as rent, is subject to income tax. The sale of inherited property by a non-resident is subject to capital gains tax. A key consideration for international estate planning is the existence of double taxation avoidance agreements (DTAAs), which can be leveraged to mitigate double taxation on the same income. To claim benefits under a DTAA, an individual must:

- obtain a tax residency certificate from their country of residence; and

- file the requisite forms in India.

In the Indian legal framework, several bilateral and multilateral instruments are of particular relevance to private clients, particularly in the domains of:

- cross-border taxation;

- estate planning; and

- succession.

DTAAs: India has entered into a wide network of DTAAs with more than 90 countries, including significant jurisdictions such as:

- the United States;

- the United Kingdom;

- Singapore;

- the United Arab Emirates;

- Mauritius; and

- Canada.

These treaties are intended to:

- eliminate or mitigate the incidence of double taxation on the same income in two jurisdictions; and

- promote fiscal cooperation.

The legislative authority for entering into such agreements is conferred under Section 90(1) of the ITA, which empowers the central government to enter into agreements with foreign countries or specified territories for, among other things:

- the avoidance of double taxation;

- the exchange of information; and

- the recovery of taxes.

In accordance with Section 90(2) of the ITA, where a DTAA contains provisions that are more beneficial to the assessee than the corresponding provisions of the ITA, the provisions of the DTAA will prevail.

The provisions of DTAAs typically include:

- concessional rates of tax on:

-

- dividends;

- interest;

- royalties; and

- fees for technical services;

- source-based or residence-based taxation of capital gains;

- mutual agreement procedures for the resolution of disputes arising from treaty interpretation.

Judicial recognition of the primacy of DTAAs was established in Union of India v Azadi Bachao Andolan (2004) 10 SCC 1, in which the Supreme Court:

- upheld the validity of treaty shopping; and

- confirmed that assessees are entitled to claim the benefit of a DTAA even where it results in a tax advantage.

Similarly, in Vodafone International Holdings BV v Union of India (2012) 6 SCC 613, the court reaffirmed the legitimacy of cross-border structures based on applicable DTAAs, subject to the limitation of benefits and anti-abuse provisions.

Multilateral Instrument: India is a signatory to the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (MLI), signed pursuant to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Sharing initiative. The MLI, which became effective in India from 1 April 2020, modifies the application of India’s bilateral tax treaties in accordance with the notified covered tax agreements (CTAs).

The legal effect of the MLI is embedded within the framework of Section 90(1) of the ITA. It introduces key anti-abuse measures into existing DTAAs, including:

- the principal purpose test, to prevent treaty abuse;

- modification of rules relating to the existence of a permanent establishment; and

- enhanced dispute resolution mechanisms, including provision for arbitration (where accepted).

India has notified over 90 bilateral tax treaties as CTAs under the MLI and the provisions of the MLI have the force of law under the ITA insofar as they are beneficial to the taxpayer.

Hague Conventions: India is not a contracting party to:

- the 1989 Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Succession to the Estates of Deceased Persons; or

- the 2015 Hague Convention on the Recognition of Foreign Public Documents Relating to Succession.

As a result, India does not follow a unified international legal regime for cross-border succession matters. In practice, such matters are addressed based on:

- domestic private international law principles;

- bilateral DTAAs, where applicable; and

- the general principle of comity of nations.

The recognition and enforcement of foreign wills or succession orders in India, particularly from common law jurisdictions, is generally governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925, read in conjunction with the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, subject to public policy considerations. India’s failure to accede to the Hague Conventions often necessitates complex legal procedures for probate and estate administration involving foreign elements.

The Supreme Court in Satya v Teja Singh (1975) 1 SCC 120 held that a foreign judgment will not be conclusive if it contravenes Indian public policy. Similarly, in Swaran Lata Ghosh v HK Banerjee, AIR 1969 Cal 252, the Calcutta (Kolkata) High Court upheld the recognition of a foreign probate where:

- the grant was made by a competent court; and

- the judgment was not opposed to Indian legal principles.

India follows a residence-based system of taxation under the Income Tax Act (ITA). The liability of an individual to income tax in India is determined with reference to their residential status, as prescribed under Section 6 of the ITA. Neither domicile nor nationality is relevant for determining tax liability under Indian law.

Determination of residential status – Section 6: An individual will be treated as resident in India in a particular previous year if they satisfy either of the following conditions as per Section 6(1):

- The individual is in India for a period of 182 days or more during the relevant year; or

- The individual is in India for a period of 60 days or more during the relevant year and for 365 days or more during the four preceding years.

Further, a new deemed residency provision was inserted by Section 6(1A) of the Finance Act, 2020, whereby an Indian citizen with a total income (excluding income from foreign sources) exceeding INR 1.5 million who is not liable to tax in any other country by reason of domicile or residence will be deemed to be resident in India, even though such person is classified as resident but not ordinarily resident (RNOR) under Section 6(6)(d).

Further as per Section 6, an individual may fall under one of the following categories:

- resident and ordinarily resident (ROR);

- RNOR; or

- non-resident.

A resident individual is considered not ordinarily resident if:

- they have been non-resident in India in nine out of 10 preceding previous years;

- their stay in India in the preceding seven years amounted to 729 days or less; and

- they are deemed to be resident under Section 6(1A) (Finance Act, 2020).

The scope of an individual’s total income chargeable to tax in India is determined in accordance with Section 5 and varies depending on residential status, as follows.

| Category | Scope of taxable income |

|---|---|

| ROR | Global income – that is, income received or accrued in India and income received or accrued outside India. |

| RNOR | Income received or accrued in India and income accruing outside India from a business controlled or profession set up in India. |

| Non-resident | Income received or deemed to be received in India, or income accruing, arising or deemed to accrue or arise in India. |

In Pradip J Mehta v Commissioner of Income Tax (2008) 300 ITR 231 (SC), it was held that to determine the status of RNOR under Section 6(6), both conditions must be satisfied – that is, the individual must have:

- been non-resident in nine out of the 10 preceding years; and

- stayed in India for 729 days or less in the preceding seven years.

Mitesh Vijay Gulati v Income Tax Officer (2025) ITAT Mumbai, it was held that:

- residential status under Section 6 is determined solely on the basis of physical presence in India; and

- days spent abroad, even for purposes such as job searching, cannot be counted towards the stay in India.

The personal tax year in India is statutorily defined under the ITA and follows the financial year cycle, commencing on 1 April of a given calendar year and concluding on 31 March of the subsequent calendar year. This period is referred to in the ITA as the ‘previous year’ and the taxability of income is determined with reference to the income earned during this 12-month period.

Under Section 3 of the ITA, the term ‘previous year’ is defined as the financial year immediately preceding the relevant assessment year. The ‘assessment year’, in turn, is defined under Section 2(9) as the 12-month period commencing on 1 April every year, during which the previous year’s income is assessed for tax. For instance, income earned during the 2024–2025 financial year (ie, from 1 April 2024 to 31 March 2025) will be assessed for tax in the 2025–2026 assessment year.

The charging provision contained in Section 4(1)(a) stipulates that income tax will be charged in respect of the total income of the previous year of every person, unless otherwise expressly provided under the ITA. The general principle is thus that income accrues and is computed with reference to the previous year but is taxed in the following assessment year.

An exception to the uniform application of the financial year as the previous year is set out in the proviso to Section 3, which states that in the case of a newly established business or a new source of income arising during the financial year, the previous year:

- will begin from the actual date of commencement of such business or source of income; and

- will end on the following 31 March.

Thus, even in the year of inception, the taxpayer is subject to the same financial year cycle.

The new Income Tax Act 2025, which received presidential assent on 21 August 2025 and has been formally notified, is set to replace the ITA. This new law, effective from 1 April 2026, will introduce the concept of a ‘tax year’ to replace the existing two-tiered system of ‘previous year’ and ‘assessment year’. This move aims to simplify the tax framework and align India’s terminology with global standards, making the tax process more streamlined and less confusing for taxpayers.

Section 2(42) of the new Income Tax Act 2025 defines a ‘tax year’ as “the period of twelve months of the financial year commencing on the 1st day of April and ending on the 31st day of March of the following year”.

For a newly established business or a new source of income, the tax year:

- begins from the date on which:

-

- the business is established; or

- the new source of income comes into existence; and

- concludes on the following 31 March.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

The taxation of individuals in India is governed by the ITA. Income tax is imposed annually through the Finance Act passed by Parliament and the applicable rates, surcharges and cesses are prescribed therein. The ITA adopts a progressive rate structure based on income slabs. Since the introduction of the alternative regime under Section 115BAC, individual taxpayers have the option to choose between two sets of tax rates:

- the old regime, which permits various deductions and exemptions; and

- the new regime, which offers lower tax rates but disallows most deductions.

Statutory framework and charging provision: The authority to levy income tax arises under Section 4(1) of the ITA, which states:

Where any Central Act enacts that income-tax shall be charged for any assessment year at any rate or rates, income-tax at that rate or those rates shall be charged for that year in accordance with, and subject to the provisions (including provisions for the levy of additional income-tax) of, this Act in respect of the total income of the previous year of every person.

The rates of tax, as well as additional levies such as surcharge and cess, are thus determined by the applicable Finance Act for each assessment year.

Components of personal income taxation: The tax liability of an individual comprises three components:

- income tax, as per the applicable slab rates;

- a surcharge on high-income categories; and

- a health and education cess on the aggregate of income tax and surcharge.

Income tax: For the 2025–26 assessment year, individuals may be taxed under either the old regime or the new regime under Section 115BAC. The old regime continues to allow deductions under various provisions (eg, Sections 80C and 80D), while the new regime restricts most such deductions but offers concessional rates.

The slab rates under the old regime are as follows:

| Total income | Tax rate |

|---|---|

| Up to INR 250,000 | Nil |

| INR 250,000–500,000 | 5% |

| INR 500,000–1 million | 20% |

| Above INR 1 million | 30% |

The basic exemption limit is enhanced for certain categories of senior citizens, as follows:

- For individuals aged 60 years or more but less than 80 years: INR 300,000.

- For individuals aged 80 years and above: INR 500,000.

Resident individuals with a total income of up to INR 700,000 (under the new regime) or INR 500,000 (under the old regime) are eligible for a rebate of 100% of income tax payable, subject to conditions.

The slab rates under the new concessional regime are as follows.

| Total income | Tax rate |

|---|---|

| Up to INR 300,000 | Nil |

| INR 300,000–600,000 | 5% |

| INR 600,000–900,000 | 10% |

| INR 900,000–1.2 million | 15% |

| INR 1.2 million–1.5 million | 20% |

| Above INR 1.5 million | 30% |

Under the amended structure introduced by the Finance Act, 2023, the new regime has been made the default regime from the 2024–2025 assessment year onwards. Taxpayers may, however, opt for the old regime, subject to the conditions specified under Section 115BAC(6). A rebate under Section 87A is also available under the new regime for individuals with income of up to INR 700,000, thereby ensuring no tax liability for such individuals.

Surcharge: In addition to income tax, a surcharge is levied on individuals with income that exceeds specified thresholds. The applicable surcharge rates under the Finance Act are as follows.

| Total income | Surcharge rate |

|---|---|

| INR 5 million–10 million | 10% |

| INR 10 million–20 million | 15% |

| INR 20 million–50 million | 25% |

| Above INR 50 million | 37%* |

* Pursuant to amendments introduced in the Finance Act 2023, the maximum surcharge rate on certain types of income – particularly those covered under Sections 111A, 112 and 112A (capital gains on equity shares and mutual funds) – is capped at 25%, even where total income exceeds INR 50 million.

Health and education cess: A cess at the rate of 4% is levied on the total of income tax and surcharge payable, as per the mandate of successive Finance Acts. This cess is earmarked for health and education funding and is uniformly applicable to all individual taxpayers, regardless of income.

In All India Federation of Tax Practitioners v Union of India (2007) 293 ITR 265 (SC), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of service tax and reiterated the power of Parliament to enact Finance Acts annually to impose tax and fix applicable rates.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The computation follows a sequential process that involves the classification of income under specific heads, aggregation into gross total income (GTI) and reduction of eligible deductions to arrive at the total income, which is the taxable base.

The term ‘total income’ is defined under Section 2(45) of the ITA as follows: ‘“total income’ means the total amount of income referred to in section 5, computed in the manner laid down in this Act.”

Thus, the determination of the taxable base involves computing income in accordance with Sections 14–59, subject to deductions under Chapter VI-A and other applicable provisions.

In determining the taxable base, income is classified under the following heads, as enumerated in Section 14:

- income from salaries (Sections 15–17);

- income from house property (Sections 22–27);

- profits and gains of business or profession (Sections 28–44DB);

- capital gains (Sections 45–55A); and

- income from other sources (Sections 56–59).

Each head has distinct computation mechanisms, permissible exemptions and allowances, and income is computed separately under each head. The aggregate of income computed under all five heads constitutes the GTI.

Certain types of income are excluded at this stage, including those that are exempt under:

- Section 10;

- Section 11 (income of charitable or religious trusts); and

- other special provisions.

From the GTI, various deductions are allowed under Chapter VI-A (Sections 80C to 80U), which result in the determination of the total income.

In CIT v GR Karthikeyan (1993) 201 ITR 866 (SC), the Supreme Court held that:

- the definition of ‘income’ under Section 2(24) is inclusive and not exhaustive; and

- income under each head must be computed according to the specific provisions applicable to that head.

The principle that deductions are allowable only after computing gross total income under the specified heads was also reaffirmed in HH Sir Rama Varma v CIT (1994) 205 ITR 433 (SC).

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

Under Section 139(1) of the ITA, every person (including individuals, firms, limited liability partnerships (LLPs) and companies) whose total income during the previous year exceeds the basic exemption limit must file an income tax return within the prescribed due date. For the 2025–2026 assessment year:

- individuals must file by 31 July 2025;

- those subject to audit under Section 44AB (including firms, LLPs and companies) must file by 31 October 2025; and

- those undertaking international or specified domestic transactions governed by Section 92E must file by 30 November 2025.

In addition, return filing is mandatory irrespective of income levels if the assessee satisfies conditions prescribed under the seventh proviso to Section 139(1), introduced by the Finance (No 2) Act, 2019, such as:

- deposits over INR 10 million in a current account;

- expenditure exceeding:

-

- INR 200,000 incurred on foreign travel; or

- INR 100,000 on electricity; and

- foreign assets held or signing authority over foreign accounts.

Under Section 139(1), non-resident Indians must also file an income tax return if their total income accruing or arising in India exceeds the basic exemption limit of INR 250,000.

Forms are prescribed under Rule 12 of the Income Tax Rules (ITR), 1962, based on the status and nature of income of the assessee, as follows.

| ITR form | Applicable to ... |

|---|---|

| ITR-1 (Sahaj) | Resident individuals with income from salary, one property and other sources (excluding lottery, racehorses), total income ≤ INR 5 million. |

| ITR-2 | Individuals/Hindu undivided families (HUFs) with income from capital gains, more than one property or foreign assets. |

| ITR-3 | Individuals/HUFs with income from business or professions. |

| ITR-4 (Sugam) | Individuals, HUFs and firms (other than LLPs) opting for presumptive taxation under Section 44AD, 44ADA or 44AE. |

| ITR-5 | Partnership firms and LLPs. |

| ITR-6 | Companies (except those claiming exemptions under Section 11). |

| ITR-7 | Persons including companies required to furnish return under Section 139(4A), 139(4B), 139(4C), or 139(4D) (eg, charitable trusts, political parties, etc). |

Failure to comply with the provisions relating to the filing of return of income under the ITA attracts penal and interest consequences under various sections, as follows.

| Nature of default | Provision | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Delay in filing return | Section 234F | INR 5,000 if filed after due date but before 31 December; INR 1,000 if total income ≤ INR 500,000. |

| Non-payment/shortfall in advance tax | Sections 234B and 234C | Interest levied at 1% per month/part thereof. |

| Delay in filing return where tax is unpaid | Section 234A | 1% interest per month from due date until filing. |

Liability under these sections is mandatory and the interest is compensatory, not penal, in nature, as upheld in multiple judicial pronouncements, including CIT v Anjum MH Ghaswala [(2001) 252 ITR 1 (SC)].

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

Under the ITA, individuals are entitled to various exemptions and deductions to reduce their taxable income. This relief varies depending on the tax regime opted for – either:

- the old regime (with deductions and exemptions); or

- the new regime under Section 115BAC (which excludes most deductions unless specifically allowed).

These exemptions are primarily enumerated under Sections 10–13A of the ITA and are applicable subject to prescribed conditions under the Income Tax Rules, 1962 and various circulars and notifications issued by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), as follows.

| Nature of income | Section | Exemption details/conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural income | Section 10(1) | Fully exempt; however, the partial integration method applies if non-agricultural income exceeds the basic exemption limit. |

| Leave travel concession | Section 10(5) | Exempt for two journeys in a block of four years, subject to conditions prescribed under Rule 2B. |

| Gratuity | Section 10(10) | Fully exempt for government employees; for others, exempt up to INR 2 million as per the limit notified under Notification 16/2019. |

| Commuted pension | Section 10(10A) | Fully exempt for government employees; partly exempt for non-government employees depending on receipt of gratuity. |

| Leave encashment on retirement | Section 10(10AA) | Fully exempt for government employees; exempt up to INR 300,000 for non-government employees as per CBDT Circular 8/2008. |

| Retrenchment compensation | Section 10(10B) | Exempt to the extent that it is less than INR 500,000, actual compensation or an amount as per Section 25F of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. |

| Voluntary Retirement Scheme compensation | Section 10(10C) | Exempt up to INR 500,000, subject to the scheme being in accordance with Rule 2BA. |

| Employer's contribution to Recognised Provident Fund | Section 10(12) | Exempt up to 12% of salary; interest exempt up to 9.5% per annum as per Rule 6 of Part A of Fourth Schedule. |

| House Rent Allowance (HRA) | Section 10(13A) | Exempt as per Rule 2A: the lowest of actual HRA, rent paid minus 10% of salary or 40–50% of salary. depending on city of residence. |

| Income of registered charitable trusts/institutions | Section 11–13 | Exempt subject to conditions, including the application of 85% of the income for charitable or religious purposes. |

| Share of profit from partnership firm | Section 10(2A) | Fully exempt in the hands of the partner, to the extent that such income is exempt in the hands of the firm under Section 10(2A). |

| Long-term capital gain (LTCG) on equity (up to 100,000) | Section 112A* | LTCG on listed equity shares or equity-oriented mutual funds is exempt up to INR 100,000; balance taxed at 10% without indexation. |

* Section 10(38) (which previously exempted LTCG on listed equity shares) was withdrawn from the 2019–20 assessment year. Under Section 112A, LTCG on listed equity shares or equity-oriented mutual funds is levied at a rate of 10% (without indexation), after an annual exemption of INR 100,000.

Under the old tax regime, individuals and HUFs are entitled to claim deductions under Chapter VI-A of the ITA to reduce their gross total income. These deductions are available under various provisions, ranging from Section 80C to Section 80U, which relate to specified investments, expenditures and social welfare contributions. The cumulative deduction under Sections 80C, 80CCC and 80CCD(1) is capped at INR 150,000, with certain additional deductions allowed under other provisions. These deductions are not available under the new regime under Section 115BAC, unless specifically notified.

In case of arrears or advance salary, relief is available under Section 89 read with Rule 21A, allowing recalculation to avoid excessive tax in a single year.

Resident individuals with a total income of up to INR 700,000 (under the new regime) or INR 500,000 (under the old regime) are eligible for a rebate of 100% of the income tax payable, subject to conditions.

In CIT v Saurashtra Cement & Chemical Industries Ltd [(2010) 33 DTR (SC) 579], the Supreme Court held that reliefs and deductions must be interpreted liberally in favour of the assessee when ambiguities arise, especially under beneficial provisions such as Chapter VI-A.

Individuals, especially non-residents, can claim tax benefits under the double taxation avoidance agreements (DTAAs) that India has entered into with many countries. These treaties ensure that income is not taxed twice. For instance, the India-UAE DTAA offers a significant benefit: capital gains from the sale of mutual fund units in India are not taxable in India for a resident of the United Arab Emirates, since mutual fund units are treated as distinct from ‘shares’ and gains are taxable only in the investor’s country of residence.

To avail of this and similar DTAA benefits, an individual must:

- obtain a tax residency certificate (TRC) from the tax authorities of their country of residence; and

- submit Form 10F through the Indian income tax portal, which is a self-declaration providing details that are not always present on the TRC.

By fulfilling these requirements, non-residents can ensure they receive beneficial tax treatment, which may include:

- a lower or zero rate of tax; and

- a refund of any tax deducted at source.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Capital gains are chargeable to income tax under Section 45 of the ITA, which stipulates that any profits or gains arising from the transfer of a capital asset effected in the previous year will be taxable in the year in which the transfer takes place. The nature of the gain depends on the period of holding as defined in Sections 2(29A), 2(29B), 2(42A) and 2(42B). The tax rates depend on the nature of the gain, as follows.

| Type of asset | Holding period | Nature of gain | Applicable tax rate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listed equity shares/equity-oriented mutual funds | ≤ 12 months | Short-term capital gain (STCG) – Section 111A | 15% (for transfers before 23 July 2024); 20% (for transfers on or after 23 July 2024, pursuant to the Finance (No 2) Act 2024). |

| Listed equity shares/equity-oriented mutual funds | > 12 months | LTCG – Section 112A | 12.5% (exempt up to INR 125,000) |

| Other assets (eg, immovable property) | ≤ 24 months (property)/36 months (others) | STCG – Section 48 | Normal slab rates |

| Other assets (eg, immovable property, unlisted shares) | > 24/36 months | LTCG – Section 112 |

12.5% without indexation is applicable on or after 23 July 2024. (20% with indexation is the old regime, which is available for resident individuals and HUFs.) |

* Rates are subject to surcharge and health and education cess as per the Finance Act.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

Under the ITA, the computation of taxable capital gains is governed by Section 48. The law prescribes that the following may be deducted from the full value of consideration received or accruing on the transfer of a capital asset:

- expenditure incurred wholly and exclusively in connection with the transfer; and

- the cost of the acquisition and cost of improvement of the asset.

In the case of long-term capital assets, these costs are adjusted for inflation through the Cost Inflation Index as per Rule 48 of the ITR, 1962.

Special computation provisions apply in certain cases:

- The first proviso to Section 48 provides that for non-residents transferring shares or debentures of an Indian company, the computation must be carried out in the same foreign currency in which the investment was made, before reconversion into Indian currency.

- The second proviso to Section 48 denies indexation benefits for specific securities, such as bonds or debentures (other than capital indexed bonds issued by the government).

- The third proviso to Section 48 overrides the first and second provisos in cases that are specifically notified.

The Supreme Court in CIT v BC Srinivasa Setty [(1981) 128 ITR 294 (SC)] held that where the cost of acquisition of an asset cannot be determined – such as in the case of self-generated goodwill – the computational mechanism fails, rendering such gains outside the ambit of capital gains taxation unless specifically brought within it by statutory amendment.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

The obligation to report capital gains in an income tax return arises under Section 139(1) of the ITA, which mandates every person whose total income exceeds the maximum amount not chargeable to tax to furnish a return by the prescribed due date. This requirement extends to cases where capital gains are chargeable to tax, even if the taxpayer’s other income is below the basic exemption limit, by virtue of Section 139(1) read with Rule 12 of the ITR, 1962.

The prescribed forms relevant for capital gains reporting are as follows.

| ITR form | Eligible assessee | Income covered |

|---|---|---|

| ITR-2 | Individuals and HUFs. | Capital gains (short-term or long-term) and other income, excluding income from business or professions. |

| ITR-3 | Individuals and HUFs. | Income from business or profession and capital gains. |

| ITR-6 | Companies (other than those claiming exemption under Section 11). | Capital gains and other taxable income. |

The filing of a return reporting capital gains is compulsory where such gains are taxable, regardless of whether the taxpayer’s total income after deductions falls below the basic exemption threshold. Non-resident individuals are equally bound by this requirement if they have capital gains that are chargeable to tax in India.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

As outlined in questions 2.4 (a)–(c), capital gains taxation in India is governed by the ITA, with:

- computation provisions under Sections 45–55A; and

- tax rates prescribed under Sections 111A, 112 and 112A.

Key exemptions under Sections 54 to 54GB include the following.

| Section | Nature of relief | Qualifying conditions |

|---|---|---|

| 54 | Exemption on LTCG from the transfer of a residential house if invested in another residential house in India. | Purchase within two years or construction within three years; deposit in Capital Gains Account Scheme if not utilised before filing return. |

| 54EC | Exemption on LTCG from the transfer of land or buildings if invested in specified bonds. | Investment within six months; maximum INR 5 million; lock-in period of five years. |

| 54F | Exemption on LTCG from the transfer of any long-term capital asset (other than residential house) if invested in a residential house. | Proportionate exemption; taxpayer must not own more than one other residential house on the date of transfer. |

| 54GB | Exemption on LTCG from the transfer of residential property if invested in equity shares of eligible startups. | Subscription before the due date of return; startup to utilise funds for the purchase of new assets. |

In Viral Rajendra Patel v PCIT, the tribunal held that a taxpayer could claim a Section 54F exemption even if the investment was made by purchasing land for the construction of a house and construction was completed beyond the statutory two-year period for purchase, as long as it was within the three-year period allowed for construction.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

In India, there is no estate duty or inheritance tax currently in force, as the Estate Duty Act, 1953 was repealed by the Estate Duty (Abolition) Act, 1985. Consequently, the mere act of inheriting property – whether movable or immovable – does not attract tax in the hands of the legal heir. However, tax implications arise under the ITA when such inherited assets subsequently generate income or are transferred. Section 56(2)(x), read with its proviso, specifically excludes from the scope of ‘income from other sources’ any sum of money or property received under a will or by way of inheritance.

Any income subsequently accruing from such property – such as rent, interest, dividends or gains upon transfer – will be taxable under the relevant head of income. Upon the transfer of an inherited capital asset, taxation arises under Section 45, with:

- Section 49(1) deeming the cost of acquisition to be that of the previous owner; and

- Section 2(42A) providing that the holding period of the previous owner is also to be considered.

The applicable tax rate is determined in accordance with Section 111A, 112 or 112A, depending on:

- the nature of the asset; and

- the period for which it is held.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The taxable base is computed not on the principal value of the inherited asset but on:

- the income generated from it; or

- the capital gains realised upon its transfer.

Section 48 prescribes the computation mechanism for capital gains; and the second proviso to Section 48 permits indexation benefits for long-term capital assets. The inclusion of the previous owner’s holding period under Section 2(42A) can result in the asset being treated as long term, thereby enabling a lower tax rate and greater exemptions.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

Section 139(1) of the ITA mandates the filing of a return of income if the total income (before claiming the exemption under Section 56(2)(x) or Section 10(2)) exceeds the maximum amount not chargeable to tax – that is:

- INR 250,000 for individuals below 60 years;

- INR 3 million for resident senior citizens (individuals aged 60 years or above but under 80 years); and

- INR 500,000 for resident super-senior citizens (individuals aged 80 years or above).

The form to be used depends on:

- the type of assessee; and

- the nature of the income.

Section 139(4) allows belated returns, but delays attract late fees under Section 234F and interest under Sections 234A, 234B and 234C. The legal obligation applies equally to individuals, HUFs and bodies corporate, with prescribed forms under Rule 12 of the ITR, 1962.

| Assessee category | Relevant section/rule | Applicable form | Due date (2025–2026 assessment year) | Late fee (Section 234F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual/HUF (no business income) | Section 139(1), Rule 12(1)(a) | ITR-2 | 31 July 2025 | INR 1,000 (income ≤ INR 500,000)/INR 5,000 (otherwise) |

| Individual/HUF (business/profession) | Section 139(1), Rule 12(1)(b) | ITR-3 | 31 October 2025 | INR 1,000 (income ≤ INR 5L)/INR 5,000 (otherwise) |

| Company (other than Section 11 entities) | Section 139(1), Rule 12(1)(d) | ITR-6 | 31 October 2025 | INR 5,000 |

| Company claiming Section 11 exemption | Section 139(4A), Rule 12(1)(e) | ITR-7 | 31 October 2025 | INR 5,000 |

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

The statute provides for specific exemptions and reliefs. The proviso to Section 56(2)(x) exempts property received under a will or by inheritance from gift taxation. Section 10(2) exempts from tax any sum received by a member from a HUF. Exemptions under Sections 54, 54F and 54EC apply where capital gains from the transfer of an inherited asset are reinvested in a manner prescribed under those sections. Section 54EC provides for an exemption if the gains are invested in specified bonds within six months.

Key exemptions and reliefs on inherited assets include the following.

| Provision | Nature of relief | Key conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Section 56(2)(x) – Proviso | Exclusion from gift tax. | Property must be received under will or inheritance. |

| Section 10(2) | Exemption for sum from HUFs. | Must be a member of the HUF. |

| Section 54 | Exemption for LTCG on house property. | Purchase within one year before or two years after; construction within three years. |

| Section 54F | Exemption for LTCG on other assets. | Investment in one residential house; no ownership of >1 house on the date of transfer. |

| Section 54EC | Exemption via investment in specified bonds. | Investment within six months; maximum INR 5 million. |

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Investment income in India is governed by the ITA, together with relevant rules, notifications and judicial precedents. Such income may comprise:

- dividends;

- interest; and

- capital gains arising from:

-

- securities;

- mutual funds;

- deposits; and

- other investment instruments.

The tax treatment depends on:

- the nature of the income;

- the residential status of the assessee as determined under Section 6; and

- the specific charging and rate provisions under the ITA.

Dividends received from domestic companies are taxable under Section 56(2)(i) in the hands of the shareholder at the applicable slab rate in the case of residents. In the case of non-residents, Section 115A prescribes a 20% rate on gross dividend income, subject to the beneficial provisions of an applicable DTAA. Interest income is generally taxed under the head ‘income from other sources’ at slab rates for residents and at concessional rates for non-residents under:

- Section 115A (20%);

- Section 194LC (5% for specified borrowings); and

- Section 194LD (5% for certain rupee-denominated bonds and government securities).

Capital gains taxation is governed by Sections 45–55A, with concessional rates prescribed in:

- Section 111A (15% for short-term gains on equity shares/units where securities transfer tax (STT) is paid);

- Section 112A (10% for long-term gains exceeding INR 100,000 on such equity assets); and

- Section 112 (20% for other long-term assets with indexation).

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

For dividends and interest, the taxable base is the gross amount received, reduced only by such deductions as are specifically allowed under Section 57(iii), which caps interest expenditure related to dividend income at 20% of such income. In the case of capital gains, Section 48 prescribes the computation mechanism: the sale consideration less the cost of acquisition/improvement and expenditures incurred wholly and exclusively in connection with such transfer. For long-term capital assets (as defined in Section 2(29A) read with Section 2(42A)), indexed cost is applied – except in cases covered by Section 112A, where indexation is unavailable. The holding period for classification between short-term and long-term varies by asset type, with special periods prescribed for:

- listed equity shares;

- units of equity-oriented funds; and

- zero-coupon bonds.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

Section 139(1) mandates the filing of an income-tax return where the total income before giving effect to exemptions exceeds the maximum amount not chargeable to tax. The return form applicable depends on:

- the type of taxpayer; and

- the nature of the income.

| Taxpayer type | Nature of investment income | Applicable ITR form* |

|---|---|---|

| Individual/HUF without business income | Dividend, interest, capital gains | ITR-2 |

| Individual/HUF with business/profession income | Any investment income | ITR-3 |

| Partnership firms, LLPs, companies | Any investment income | ITR-5/ITR-6 |

| Non-resident (individual/company) | Dividend, interest, capital gains | ITR-2 / ITR-6 as applicable |

* The statutory due date is 31 July for non-audit cases and 31 October for audit cases.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

The ITA provides for several types of relief aimed at:

- avoiding double taxation; and

- incentivising specific investments.

Section 10(34) exempts certain notified dividends; while Section 10(15) exempts interest on specified bonds, securities and savings instruments notified by the central government. Capital gains exemptions are available under Sections 54, 54EC, 54F and 54EE, subject to:

- reinvestment in specified assets; and

- prescribed monetary/time limits.

Deductions for interest on savings bank accounts and deposits are available under Sections 80TTA and 80TTB. Non-residents may avail of treaty relief under Sections 90 and 90A, provided that procedural compliance (including a TRC) is met.

Judicial guidance, such as that provided in Azadi Bachao Andolan v Union of India [(2003) 263 ITR 706 (SC)], affirms that treaty benefits cannot be denied where statutory conditions are fulfilled. Further, in CIT v Reliance Petroproducts Pvt Ltd [(2010) 322 ITR 158 (SC)], the Supreme Court clarified that penalties under Section 271(1)(c) will not be attracted merely due to the rejection of a claim, provided that the particulars were fully disclosed.

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

The taxation of real estate transactions in India is governed primarily by:

- the ITA for direct taxes;

- the Goods and Services Tax (GST) Act, 2017; and

- relevant state stamp duty laws for indirect taxes.

The legal regime applies differently depending on whether:

- the property is held as a capital asset or stock in trade;

- the transaction is a transfer, lease or development arrangement; and

- the assessee is an individual, body corporate or partnership.

Beyond the central direct and indirect taxes, real estate transactions and ownership are also subject to various state and local government levies. Key among these are stamp duty and registration fees, which are mandatory at the time of the property transfer and are governed by respective state laws. The rates for these vary significantly across India (eg, typically between 4–7%). Additionally, owners are subject to an annual property tax (also known as house tax) levied by the local municipal body. The rates and calculation methods for property tax are not uniform and are determined by the specific city or municipal corporation.

When immovable property is received without consideration, such as by way of a gift, its taxation is governed by the ITA. The recipient may be taxed on the property’s stamp duty value under Section 56(2)(x). However, this provision has specific and significant exemptions. A gift of immovable property from a ‘specified relative’ is completely exempt from tax in the hands of the recipient, regardless of the value. This exemption also applies to property received under a will or inheritance.

Under the ITA, gains from the transfer of real estate are taxable as capital gains in accordance with Section 45. LTCGs arise where the holding period exceeds 24 months (Section 2(42A)), taxable at 20% (Section 112) with indexation benefits – although amendments to the Finance Act, 2024 introduced a 12.5% rate without indexation; whereas STCGs are taxed at the normal slab rates applicable to the assessee. Where the property is held as stock in trade, profits are taxed as business income at applicable rates. In addition, Section 56(2)(x) taxes the recipient on the receipt of immovable property for inadequate consideration if the difference between the stamp duty value and consideration exceeds the prescribed threshold.

For indirect taxes, GST at 1% (affordable housing) or 5% (other residential property) without input tax credit applies to properties that are under construction, as per Notification 03/2019-Central Tax (Rate). Completed properties and the resale of ready-to-occupy units are outside the scope of GST but remain subject to stamp duty and registration fees under state laws (rates vary by state, generally between 4–7%).

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

Under the ITA, the computation of taxable gains from the transfer of real estate is governed by Section 48, which prescribes that the full value of consideration will be reduced by:

- the indexed cost of acquisition;

- the indexed cost of improvement; and

- expenses incurred wholly and exclusively in connection with such transfer.

Where the consideration declared is less than the value adopted or assessed for stamp duty purposes, Section 50C mandates the substitution of such stamp duty value as the deemed full value of consideration, subject to the safe harbour tolerance limit (currently 10%) introduced by the Finance Act, 2018. Where the property constitutes stock in trade, the taxable base is computed as business profits under Sections 28–43D, determined by deducting allowable expenditure from the sale proceeds.

Under indirect taxation under the GST Act, Section 15 provides that the value of supply will be the transaction value – that is, the price actually paid or payable, inclusive of all incidental charges, fees or amounts that the supplier is liable to collect from the recipient, but excluding taxes levied under the GST law itself.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

Under Section 139(1) of the ITA, every person whose total income, before claiming exemptions under sections such as Sections 54, 54F and 54EC, exceeds the maximum amount not chargeable to tax must file a return of income.

The applicability of the return requirements is as follows.

| Return form | Applicable to ... | Relevant disclosure |

|---|---|---|

| ITR-2 | Individual/HUF without business/professional income | Schedule capital gains |

| ITR-3 | Individual/HUF with business/professional income | Schedule capital gains + business schedules |

| ITR-6 | Companies | Schedule capital gains + corporate disclosures |

| ITR-4 | Presumptive income cases (Section 44AD/ADA/AE) | Generally, not for capital gains |

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

The ITA sets out a comprehensive framework granting exemptions and deductions on income arising from the transfer or ownership of immovable property – in particular, to incentivise reinvestment and promote housing. This relief operates by either:

- excluding specific gains from the taxable base; or

- permitting deductions against total income.

| Provision | Eligible transaction | Quantum of relief | Key conditions | Time limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 54 | LTCG from the transfer of a residential house. | Exemption proportionate to reinvestment. | New asset must be a residential house in India. | Purchase: one year before/two years after. Construction: Three years after transfer. |

| Section 54F | LTCG from transfer of asset other than residential house. | Exemption proportionate to reinvestment of net consideration. | Assessee must not own more than one other residential house. | Purchase: One year before/two years after. Construction: Three years after transfer. |

| Section 54EC | LTCG from transfer of any long-term asset. | Up to INR 5 million. | Investment in specified bonds. | Within six months. |

| Section 80C | Repayment of housing loan principal. | Up to INR 150,000. | Loan from specified institutions. | During the year. |

| Section 24(b) | Interest on housing loan. | INR 200,000 (self-occupied), unlimited (let-out). | Loan must be for acquisition/construction/repair. | During the year. |

(a) What are they and what are the applicable rates?

Apart from the ITA, India’s direct tax framework encompasses a limited set of transaction-specific levies, each governed by its respective statute. These taxes operate independently of income tax, with their own:

- charging provisions;

- taxable base; and

- compliance mechanisms.

STT, introduced under Chapter VII of the Finance (No 2) Act, 2004, is levied on the purchase or sale of specified securities executed through a recognised stock exchange. The applicable rates, prescribed under Section 98 read with the relevant notifications, generally range from 0.001% to 0.2% of the transaction value, depending on the class and nature of the transaction.

Commodities transaction tax (CTT), introduced under Chapter VII of the Finance Act, 2013, applies to the sale of non-agricultural commodity derivatives traded through recognised associations. Under Section 116 of the Finance Act, 2013, the statutory rate is fixed at 0.01% of the taxable transaction value.

Stamp duty on securities, codified in Part AA of Chapter II of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899 (as amended with effect from 1 July 2020), is imposed on the issue, transfer or sale of securities. The applicable rates, prescribed in Schedule I of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, generally vary between 0.005–0.015%, contingent on the category of instrument.

The equalisation levy, governed by Chapter VIII of the Finance Act, 2016 (as amended), applies to specified digital transactions. Section 165 imposes a levy of 6% on consideration for online advertising and related services; while Section 165A prescribes a 2% levy on consideration for e-commerce supply or services.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The method for determining the taxable base is prescribed under each specific statute. For STT and CTT, the taxable value is the transaction amount as determined in accordance with, respectively:

- Section 99 of the Finance (No 2) Act, 2004; and

- Section 116 of the Finance Act, 2013.

In the case of stamp duty on securities, the charge is computed on the consideration amount or the market value of the security, whichever is higher, as defined under Section 21 of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899. For the equalisation levy, the taxable base is the total amount of consideration received or receivable for the specified service or e-commerce supply, as defined under Section 164(i) of the Finance Act, 2016.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

Compliance and reporting obligations for direct taxes other than income tax are prescribed under their respective statutes and rules, with clear stipulations on collection, remittance and filing requirements. While some levies are collected at source by market intermediaries, others require direct payment and reporting by the assessee.

| Levy | Collection mechanism | Statutory provision | Return/statement requirement | Governing rules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STT | Collected at source by recognised stock exchange and remitted to central government. | Sections 100 and 101 of the Finance (No 2) Act, 2004. | Periodic statement in prescribed form. | STT Rules, 2004. |

| CTT | Collected at source by recognised association and remitted to the central government. | Sections 117 and 118 of the Finance Act, 2013. | Periodic statement in the prescribed form. | CTT Rules, 2013. |

| Stamp duty on securities | Collected by stock exchange, clearing corporation, or depository; remitted to the state government. | Section 9A of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899. | Reporting to the state government. | Indian Stamp (Collection of Stamp Duty through Stock Exchanges, Clearing Corporations and Depositories) Rules, 2019. |

| Equalisation levy | Deposited directly by assessee to the central government on a quarterly basis. | Section 166 of the Finance Act, 2016. | Annual statement in Form 1. | Equalisation Levy Rules, 2016. |

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

Certain transactions are expressly excluded from the scope of STT and CTT – for instance, agricultural commodity derivatives are exempt from CTT under Section 113 of the Finance Act, 2013. Under the Indian Stamp Act, specific exemptions are provided in Schedule I, such as for:

- certain transfers between depositories; and

- specified transactions by the Reserve Bank of India.

In the case of the equalisation levy, exemptions under Section 165(2) are available where:

- the non-resident service provider has a permanent establishment in India; or

- the aggregate consideration for the specified services does not exceed INR 100,000 in a financial year.

Judicial interpretation has reinforced the mandatory nature of these compliance obligations, as seen in PILCOM v CIT [(2020) 425 ITR 312 (SC)], in which the Supreme Court held that:

- statutory collection provisions must be adhered to strictly; and

- exemptions can only be availed of within the express terms of the statute.

(a) What are they and what are the applicable rates?

India operates under a harmonised indirect tax framework primarily governed by the GST Act, which subsumes a majority of erstwhile indirect taxes such as:

- central excise duty;

- service tax; and

- state value-added tax.

In addition, certain non-GST indirect levies continue to apply under their respective statutes, such as:

- customs duty;

- stamp duty; and

- excise on specified products (eg, petroleum products, alcoholic liquor for human consumption).

The regime is destination based, taxing consumption within the taxing jurisdiction.

The GST Act is levied on:

- the supply of goods and services under:

-

- Section 9 of the Central GST Act, 2017; and

- the corresponding provisions of the state/union territory GST Acts; and

- inter-state supplies under Section 5 of the Integrated GST (IGST) Act, 2017.

The standard GST rates are 5%, 12%, 18% and 28%, as per the GST rate notifications issued under Section 9(1) read with Section 15. Certain items attract a compensation cess under Section 8 of the GST (Compensation to States) Act, 2017. Customs duty is levied under the Customs Act, 1962 at rates prescribed in the Customs Tariff Act, 1975, while stamp duty is imposed by the respective state stamp acts.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

Under Section 15 of the CGST Act, the taxable value for GST purposes is the ‘transaction value’ – that is, the price actually paid or payable, provided that:

- supplier and recipient are unrelated; and

- price is the sole consideration.

This value includes any incidental expenses, taxes (other than GST) and amounts payable by the recipient on behalf of the supplier.

Customs valuation is governed by Section 14 of the Customs Act, 1962, which adopts the transaction value of imported goods, subject to prescribed additions under the Customs Valuation (Determination of Value of Imported Goods) Rules, 2007. The stamp duty base is determined by the consideration stated in the instrument or the market value, whichever is higher, as per the applicable state law.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

Section 39 of the CGST Act mandates registered persons to furnish periodic returns as follows.

| Tax type | Governing law | Form/document | Filing frequency | Key details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGST and state GST | Section 39 of the CGST Act, 2017 and respective state GST acts | GSTR-1 | Monthly/quarterly (under the quarterly return, monthly payment (QRMP) scheme) | Statement of outward supplies; due date – 11th of the following month (monthly) or 13th of the month after quarter-end (quarterly). |

| GSTR-3B | Monthly/quarterly (QRMP scheme) | Summary return with payment of tax; due date – 20th of the following month (monthly), or 22nd/24th for quarterly filers, depending on state. | ||

| Section 44 of the CGST Act, 2017 | GSTR-9 | Annually | Annual return; due date – 31 December following the end of the financial year. | |

| Section 39(2) of the CGST Act, 2017 | CMP-08 | Quarterly | Statement-cum-challan (the way of making payments in India) for composition taxpayers; due date – 18th of the month following the quarter. | |

| IGST | IGST Act, 2017 (read with CGST return provisions) | As above | As above | Return requirements are the same as CGST/SGST, depending on registration type. |

| Customs duty | Sections 46 and 50 of the Customs Act, 1962 | Bill of entry | At the time of import | Declaration for imported goods; filed electronically through ICEGATE before arrival of goods. |

| Shipping bill | At the time of export | Declaration for export of goods; filed through ICEGATE prior to export clearance. | ||

| Stamp duty | Respective state stamp acts | Instrument with self-assessment/e-return (if applicable) | At or before execution of instrument | Duty paid via physical stamps, e-stamping or franking; some states mandate electronic returns for bulk transactions or corporate entities. |

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

Schedule III to the CGST Act specifies transactions that are treated as the supply of neither goods nor services (eg, services provided by an employee to employer in the course of their employment). Section 11 empowers the government to grant exemptions via notification – examples include:

- healthcare services;

- educational services; and

- certain types of agricultural produce.

Relief is available to exporters through zero rating under Section 16 of the IGST Act. Small businesses with an aggregate turnover below the prescribed threshold (INR 4 million for goods, INR 2 million for services or INR 1 million in special category states) are exempt from registration under Section 22.

Customs duty exemptions are available under various notifications issued under Section 25 of the Customs Act. Stamp duty concessions exist in certain states for specific transactions, such as the transfer of property to charitable trusts.

Succession in India is governed by a combination of personal laws and general statutes:

- Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs are governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, as amended;

- Muslims are governed by uncodified personal law derived from the Quran, Hadith and authoritative texts; and

- Christians and Parsis are governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925 in respect of both testamentary and intestate matters.

Section 5 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 delineates the territorial application of the act; while Sections 213–215 govern probate requirements.

The Indian courts may recognise the application of foreign succession laws if the deceased was domiciled in another jurisdiction at the time of death, particularly in relation to immovable property situated outside India. This is consistent with the principles of:

- lex situs for immovable property; and

- lex domicilii for movable property.

However, in Satya v Teja Singh [(1975) 1 SCC 120], the Supreme Court cautioned that the application of foreign law cannot be repugnant to Indian public policy.

Conflicts of law are resolved by applying settled private international law principles:

- Immovable property: Succession is governed by the law of the place where the property is situated (lex situs).

- Movable property: Succession is governed by the law of the domicile of the deceased at the time of death (lex domicilii).

Where foreign law claims applicability but conflicts with Indian statutory provisions or public policy, the Indian courts will apply the domestic statute. For instance:

- Section 5 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 expressly limits the application of other succession laws in certain cases; and

- Section 3 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 provides interpretative rules in mixed law scenarios.

India does not generally have a uniform regime of forced heirship akin to certain civil law jurisdictions. However, under Muslim personal law, fixed shares of inheritance are mandatorily allocated to specified heirs, leaving only up to one-third of the estate disposable by will (Abdul Rahim v Sk Abdul Zabar, AIR 2009 SC 1989). Hindu law, Christian law and Parsi law impose no such statutory compulsion, permitting the testator to dispose of property freely, subject to the rights of dependants under statutes such as the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007.

Where a person dies intestate, the devolution of property is determined entirely by the deceased’s personal law.

For Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs, the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 governs succession. Sections 8–13 (for males) and Section 15 (for females) prescribe the order of heirs, giving primacy to Class I heirs in the schedule. The 2005 amendment and Vineeta Sharma v Rakesh Sharma [(2020) 9 SCC 1] affirm equal coparcenary rights for daughters.

For Muslims, succession is regulated by uncodified Muslim personal law, with variations between Sunni (per capita) and Shia (per stirpes) systems. Fixed shares are allotted to sharers and the balance to residuaries; and testamentary power is limited to one-third of the estate without heirs’ consent (Abdul Rahim v Sk Abdul Zabar, AIR 2009 SC 1989).

For Christians, Sections 33–49 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 govern succession, with the spouse’s entitlement depending on the existence of lineal descendants or kin.

For Parsis, Sections 50–56 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 apply, providing equal inheritance rights for male and female heirs.

The statutory rules on intestate succession cannot be abrogated. The validity of a testamentary disposition may be challenged on recognised legal grounds, such as:

- lack of testamentary capacity;

- undue influence;

- coercion;

- fraud; or

- failure to comply with execution formalities under Sections 59–63 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925.

In H Venkatachala Iyengar v BN Thimmajamma [AIR 1959 SC 443], the Supreme Court laid down the principles for examining the genuineness of a will, emphasising the burden of proof on the propounder to establish:

- due execution; and

- the absence of suspicious circumstances.

The Indian Succession Act, 1925 is the principal law regulating wills and probate, except for certain communities whose personal laws apply (eg, Muslim succession is governed by Sharia law). Under Section 2(h), a ‘will’ is defined as the legal declaration of a testator’s intention regarding the disposal of property after death. Sections 57 and 213 specify the classes of wills requiring probate, generally mandating this for:

- wills made by Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains within certain territories; and

- all wills made by Christians and Parsis.

A written will may be governed by the law of another jurisdiction if:

- the testator is domiciled outside India at the time of death; and

- the subject matter is situated abroad.

However, the Indian courts will apply domestic conflict-of-laws principles to determine validity and often uphold foreign laws if this is consistent with Indian public policy.

Conflicts of laws are resolved by reference to:

- the testator’s domicile at the time of death for movables; and

- the lex situs (law of location) for immovables.

Sections 63–65 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 set out execution requirements; but under Section 63(c), wills executed outside India according to the law of the place of execution are generally valid in India, subject to probate where required. Recognition of foreign wills typically involves obtaining probate or letters of administration from a competent Indian court, based on authenticated copies of the foreign grant, under Sections 228–229.

Foreign wills are recognised under Sections 63, 69, 228 and 229 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, subject to compliance with Indian attestation and execution requirements. For probate of a foreign will in India, the original will or an authenticated copy must be produced, supported by proof of foreign probate, as held in Kartar Singh v Surjan Singh (AIR 1970 SC 2093).

While testamentary freedom is broad, it is subject to statutory restrictions. Under Muslim law, bequests to non-heirs cannot exceed one-third of the estate without the heirs’ consent. Under the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, coparcenary property cannot be bequeathed unless severed. Further restrictions arise under:

- the Foreign Exchange Management Act for transfers to non-residents; and

- certain state land reform laws.

Under Section 63 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, an unprivileged will must be signed by the testator (or by another person in their presence and under their direction) and attested by at least two witnesses, each of whom has either seen the testator sign or received a personal acknowledgement of their signature. The witnesses must sign in the presence of the testator, although not necessarily in each other’s presence. The signature must indicate intent to give effect to the document as a will. Non-compliance renders the will invalid, as affirmed in H Venkatachala Iyengar v BN Thimmajamma (AIR 1959 SC 443).

While registration is optional under Section 18 of the Registration Act, 1908, it is advisable as it strengthens evidentiary value (Rani Purnima Debi v Kumar Khagendra Narayan Deb, AIR 1962 SC 567). Even unregistered wills can be proved under Section 68 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 through at least one attesting witness.

Privileged wills (Sections 65–66 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925) apply to soldiers, aviators and mariners in special circumstances, allowing for:

- fewer formalities; and

- in some cases, oral execution.

Testamentary capacity under Section 59 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 requires the testator to be:

- of sound mind; and

- free from coercion, fraud or undue influence.

Alterations after execution must comply with Section 71 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925.

Best practice dictates:

- execution before independent witnesses;

- clear dating;

- avoidance of overwriting; and

- safe custody of the will, including possible deposit with the Registrar of Assurance under Section 42 of the Registration Act, 1908.

In order to ensure the validity and enforceability of a will, meticulous drafting is imperative. The will:

- should be free from ambiguity;

- must unequivocally identify the testator, including their full name, parentage and address; and

- must include the date and place of execution.

Beneficiaries must be clearly described so as to leave no scope for confusion and the properties bequeathed should be specified with precision, including complete details such as:

- location;

- survey numbers; or

- other unique identifiers.

The appointment of an executor – preferably an impartial and competent person under Section 222 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 – is strongly recommended to facilitate effective administration of the estate.

Attestation must be strictly in accordance with Section 63(c) of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which requires the signature of at least two witnesses who have no direct or indirect beneficial interest under the will, thereby mitigating the risk of challenges on the grounds of undue influence or conflict of interest. For additional legal strength, execution may be conducted in the presence of an advocate or notary; and, where appropriate, the will may be registered under Sections 40–42 of the Registration Act, 1908, which also permits secure deposit with the registrar for safekeeping.

It is considered best practice to:

- store the will in a secure location, such as with a trusted family member or legal adviser or in a bank locker; and

- maintain copies for record purposes.

Case law, including Naresh Charan Das Gupta v Paresh Charan Das Gupta, AIR 1955 SC 363, has underscored that a will must reflect the true and free intention of the testator, uninfluenced by coercion or suspicious circumstances. Observing these best practices:

- minimises the potential for litigation; and

- ensures that the testamentary wishes of the testator are honoured without obstruction.

| Element | Format/contents | Registration requirement | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testator details | Full name, parentage, address, date and place of execution. | Not mandatory; optional under Sections 40–42 of the Registration Act, 1908. | Establishes identity and date of execution; strengthens evidentiary value. |

| Beneficiaries | Full names, relationships, specific shares/entitlements. | Not mandatory. | Avoids ambiguity; reduces the risk of disputes. |

| Property details | Complete description including location, survey numbers and unique identifiers. | Not mandatory. | Ensures clarity in property disposition. |

| Executor appointment | Name and contact details of an impartial, competent person (Section 222 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925). | Not mandatory. | Facilitates administration, enforces testamentary wishes. |

| Witnesses/attestation | Minimum two witnesses; must attest signature in the presence of the testator (Section 63(c) of the Indian Succession Act, 1925). | Mandatory for validity. | Protects against undue influence, fraud or coercion. |

| Registration/safekeeping | Optional registration and deposit with the registrar or secure storage. | Optional. | Provides legal authentication, safe custody and accessibility. |

| Special instructions | Codicils, conditions, digital assets, debts, funeral wishes. | Optional. | Enhances clarity; ensures that all matters are addressed. |

A will, once the testator has died, attains finality and cannot be altered, modified or revoked in substance. Under Section 62 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, any change to a will during the testator’s lifetime must be affected through a codicil, executed and attested in the same manner as the will itself. Upon the testator’s death, the probate court is empowered only to rectify clerical or typographical errors, and only in limited circumstances, without altering the testamentary dispositions.

To ensure clarity and enforceability, the following wording is recommended for a final will:

This is my last and final will and testament, revoking all previous wills and codicils made by me. I declare that I am of sound mind and fully capable of making this will. All my property, movable and immovable, shall be distributed as set forth herein, and no other disposition shall have any effect. This will is executed voluntarily and without undue influence or coercion.

A will may be challenged before a competent court on various legal grounds, including:

- absence of testamentary capacity;

- undue influence;

- coercion;

- fraud;

- forgery; or

- non-compliance with the statutory execution and attestation requirements under Section 63 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925.

The Supreme Court in H Venkatachala Iyengar v BN Thimmajamma (AIR 1959 SC 443) held that the burden of proving due execution and a sound disposing mind lies with the propounder, who must also dispel any suspicious circumstances surrounding the will’s execution.

Where a person dies intestate (ie, without leaving a valid will), the distribution of their estate is determined by the deceased’s personal law. For example:

- Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs are governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956;

- Muslims are governed by Muslim personal law (Shariat); and

- Christians, Parsis and others are governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925.

These statutory rules allocate heirs and shares in a fixed order, and courts cannot alter this distribution. Unlike a will, intestacy cannot be ‘challenged’, except to resolve disputes over heirship or property title. The only way to avoid default intestate rules is through valid estate planning such as a will or trust.

In India, private trusts are primarily governed by the Indian Trusts Act, 1882; while public charitable or religious trusts are regulated:

- by state-specific laws such as the Maharashtra Public Trusts Act, 1950; or

- in states without specific statutes, by general legal principles.

Taxation is dealt with under the Income Tax Act (ITA) (particularly Sections 11, 12, 12A and 12AB for charitable trusts). A trust deed may stipulate governance under foreign law and the Indian courts may recognise such stipulation provided that it does not contravene Indian public policy. Additional statutes may apply depending on the nature of the trust assets, such as:

- the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) for foreign assets;

- Securities and Exchange Board of India regulations for listed securities; and

- applicable stamp acts for immovable property.

Indian conflict-of-laws principles generally apply. The law of the place in which immovable property is situated (lex situs) governs rights in such property; whereas the law expressly chosen by the settlor or inferred from circumstances governs:

- trust validity;

- administration; and

- beneficiaries’ rights.

However, the Indian courts will not apply any foreign law provisions that conflict with Indian public policy.

The ITA also recognises various other types of trusts, as follows.

Revocable trust: A revocable trust is a trust that allows the transferor to reclaim the assets or income transferred to the trust under certain conditions. Section 63 of the ITA outlines the nature of a revocable transfer. Specifically, under Section 63(a)(i), a transfer is deemed revocable if:

- it includes a provision that permits the direct or indirect retransfer of all or part of the assets or income to the transferor; or

- it grants the transferor, directly or indirectly, the right to reassume control or power over all or part of the assets or income.

In accordance with Section 61 of the ITA, any income generated from a revocable transfer of assets is considered taxable as the income of the transferor. This income must be included in the transferor’s total income for tax purposes, ensuring that the transferor remains liable for taxation on the income derived from assets over which they maintain certain rights or control.

Irrevocable trust: Section 62 of the ITA addresses irrevocable trusts and specifies exceptions to the application of Section 61. It states that Section 61 does not apply to income arising from a trust transfer that is: