Corporate restructurings across the European Union have long been on the top of the agenda to accomplish the EU single market. Some frequently used forms of restructurings are mergers by absorption, mergers by acquisitions, exchange of shares or split-offs (of business activities).

Due to the lack of harmonization of tax law at the EU level cross-border mergers still receive unfavourable tax treatment compared to national mergers. This can be seen in particular with regard to the rather conservative position on cross border mergers in Germany. In our view there are, however, a few areas where restrictive national rules may be challenged in view of more lenient EU legislation and case law.

I. Cross-border mergers in Germany

Germany, like other EU countries, has a special national tax regime to ensure that the above mentioned forms of restructurings are treated as "tax neutral". "Tax neutral" means that taxation of any built-in gains in assets and shares transferred as part of the restructuring is deferred until the transferred assets / shares are eventually sold at a later point in time.

II. Implementation of EU directives

Until 2006 this régime only applied to national reorganisations. In 2006 Germany transposed the cross-border mergers directive (2005/56/EC) into national law, amending, inter alia, the Tax on Reorganisations Act (Umwandlungssteuergesetz — UmwStG);five years later, in 2011, guidelines (Umwandlungssteuererlass) on interpreting the UmwStG were published. The implementation of the tax aspects of the EU directives thus took a rather long time: The first directive on cross border mergers at EU level dates back to as early as 1990, when the EU merger Directive (90/434/EEC) already stipulated that cross-border mergers within the EU should take place in a tax-neutral way, provided that certain conditions were satisfied.

Why, one may ask, did Germany take so long to transpose the tax aspects of the EU directives on cross border mergers and why did it take five more years to issue guidelines on it? Maybe the key reason is that in the aftermath of the first 1990 EU merger directive the transposition of the tax aspects of cross-border mergers has proven to be more difficult than the implementation of the legal aspects. Indeed, the challenge to ensure overall tax neutrality across all involved jurisdictions for the transaction is a formidable one.

The main technical problem is not so much, like with the legal issues involved in cross-border mergers, that each country concerned may apply its own reorganisation (tax) régime and that these régimes often differ from one another. This is not to say that this is not an important technical issue:

- One only has to bear in mind that in a typical reorganisation

there are potentially quite a few national tax régimes

affected which need to be brought into line. The reorganisation

must be viewed as tax neutral by all of the following

jurisdictions, the jurisdiction:

- where the involved companies are domiciled or managed

- where the involved shareholders are resident

- where assets of the companies are located (foreign PEs)

- If only one of the jurisdictions does not view the restructuring as tax neutral pursuant to its own tax law the overall tax neutrality is lost. The thrust of the 2006 amendments is therefore aimed at linking the German reorganization tax régime with those of other countries. Accordingly the amendments ensure that Germany recognises foreign reorganisation tax deferral régimes if they are similar to the German one (which is determined by an equivalence test). Further, the scope of the application of the Tax on Reorganization Act has been extended to cover also foreign entities and even allows for foreign entities to be the sole participants of a merger under the Act, if the assets are located in Germany, e.g. in the PE (permanent establishment) of a foreign entity.

However, another technical problem has not been solved in a satisfactory manner, namely the inherent conflict of cross-border mergers with national exit taxation rules. Often, a jurisdiction loses its taxing right with respect to built-in gains in the transferred assets / shares as a result of a cross-border transaction. This is a result of the application of the relevant double tax treaties in place between the jurisdictions concerned.

The German taxing right is lost, where:

- as a result of the merger assets are deemed to have been transferred to the foreign country and thus form part of a foreign permanent establishment or corporate entity (see Art. 7 OECD master agreement) or

- the assets are still situated in Germany but Germany loses the right to tax the sale of any new shares issued to the shareholders in return for the transferred assets (or in return for the transferred shares in case of a share-for-share transfer) (see Art. 13 (5) OECD Master Agreement).

Hence Germany granting the deferment (the so called "tax neutrality") may be prevented from making use of its (deferred) taxation right when the deferment ends. This is viewed as being unacceptable by the German legislator and the German tax administration.

It is therefore no surprise that the German 2006 UmwStG denies tax neutrality in all situations where German taxing rights with regard to a later sale of the transferred assets / shares are being restricted as a result of the reorganization (so called "exit taxation").

- Examples for tax pitfalls

For this reason we now have a situation in Germany where EU cross border mergers are often legally feasible but still have many tax pitfalls. This can be illustrated by the following examples:

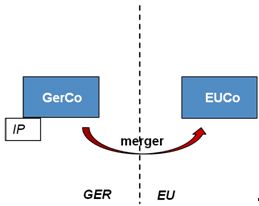

Example 1: a side-stream merger of a German company into an EU company (i.e. a company resident in another EU Member State).

Whether or not this is tax-neutral depends on the location of the intellectual property (IP). Theoretically it could remain in Germany as the merger results in EU Co having a PE in Germany. However, the 2011 guidelines tend to allocate the IP to EU Co's head office in the other EU state rather than to the remaining German PE, leading to the loss of Germany's taxing rights.

This exit taxation principle equally applies at the level of the shareholders with regard to the built-in gains in their participations.

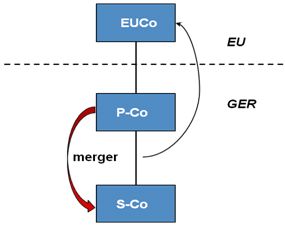

Example 2: a German company (P-Co) owned by a foreign company (EU Co) enters into a downstream merger with its German subsidiary (S-Co).

Under the 2006 guidelines, since Germany loses the right to tax the participation in S-Co, there is a deemed dividend up to EU Co, 5% of which is subject to German tax.

III. Outlook and current possibilities to use EU law to override German law

It is worth noting that the role of exit taxation within cross-border reorganizations is now discussed in greater depth in Germany in the aftermath of the recent European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruling in the case National Grid Indus BV (of 29 November 2011, C-371/10). One conclusion from this case could be that going forward Germany may at least have to provide for an option to defer any exit taxation. German tax authorities are currently awaiting two other cases pending at the ECJ before proceeding with the implementation of this judgement. It is likely that the option of a deferment may ultimately only be available against interest and security which may deter business to make use of this option.

An alternative concept is to defer not the (exit) tax but rather the triggering point of taxation in a cross-border restructuring context: according to this approach an immediate exit tax would be replaced by the guarantee for Germany to tax the built-in gains when a later sale of the transferred assets / shares occurs. This concept would ensure the similar treatment of cross-border mergers and national mergers. The problem with this approach is that it runs counter to most of the double tax treaties (see above).

However, it is often overlooked that this concept already forms part of the 2005 EU merger directive, even though it is limited there to share-for-share transfers. Art 8 (6) provides that under certain circumstances the exit state waives the right to tax shareholders at the time of restructuring in return for a guaranteed right to tax at the time of later alienation of shares (thus promulgating a treaty override with respect to Art. 13 (5) OECD Master Agreement). Further support for this concept can be found in the reasoning of the German Federal Fiscal Court in itslandmark decision on exit tax for natural persons (BFH, 17 July 2008, I R 77/06).

While the discussion on how to take away the tax pitfalls for cross border mergers is still going on, there is nothing to prevent a business aiming to restructure its activities to invoke these options offered in the ECJ case law and in the EU directives in front of their respective tax authorities. Tax rulings from all jurisdictions affected by the transaction should be obtained to ensure that these options are viewed by all concerned tax authorities in a similar way.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.