Author: Roger Hischier, Certified Specialist SAV Labour Law at Humbert Heinzen Hischier Rechtsanwälte

The unknown is always scary. And from a legal perspective alone, there is usually more than enough of this in the case of international employee assignments, because when deploying employees abroad, we have to deal with at least two different legal systems that need to be observed: namely the legal system of the country from which an employee is sent abroad for a work assignment, and then the legal system of the country or countries in which the employee's place of assignment is located. If the employee has a different nationality and also lives in a third country, these legal systems must also be observed.

Autonomous legislation

Each state determines its own legal system autonomously. Each state also assumes that its legal system is the best - as it is the most familiar - and therefore always wants to see it applied. Particularly about public law, this idea is therefore also consistently implemented by means of a clearly defined mandatory intention to apply the law and a separate jurisdiction.

A certain softening of this principle is achieved through international treaties in which the contracting states coordinate the scope of application of their legal systems in cross-border situations and, depending on the case, regulate them differently from national legislation.

Relevant areas of law

In the case of an international employee assignment, the provisions of the following legal areas are of particular importance:

- Residence and work permit law

- Tax law

- Social security law

- Labour law

Of these four areas of law , the first three are part of public law and are therefore generally not subject to party autonomy. Each state is obliged to determine which nationals may reside and work on its territory and under what conditions. In the relationship between the EU states and Switzerland, there is an international treaty in this area in the form of the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons, which contains deviations from the national legal systems and guarantees equal rights between the nationals of the contracting states.

The Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons then also coordinates social insurance for the aforementioned nationals - also based on the principle of equal treatment . Without a corresponding treaty, social insurance is also one of the areas of law that each state determines autonomously, particularly regarding the obligation to pay contributions. This in turn can lead to a double burden in the case of international employee assignments, as an employee is subject to social insurance in both the country from which he or she is sent abroad and in the country of assignment and is therefore liable to pay contributions in both countries. The same applies to tax law.

However, Switzerland has concluded various double taxation agreements worldwide to avoid double taxation. In the area of labour law, a distinction is regularly made between public and individual labour law. The first group includes labour law standards, which covers working time, occupational safety and health regulations. These are mandatory at the place of work and compliance with them is monitored by the authorities and non-compliance is penalised. In Switzerland, these provisions are governed by the Labour Act and the Accident Insurance Act or the corresponding ordinances. Even in the area of individual labour law, there is no unrestricted freedom of contract; instead, all countries regard the employee as a party to the contract requiring special protection from the employer, and this idea of protection is implemented by means of mandatory provisions that may not be amended to the disadvantage of the employee. Employees are also generally treated favourably in procedural terms, as they are guaranteed simplified and cost-free court proceedings. The question of which court has jurisdiction in an employment relationship with points of contact with several countries and which law it applies can be found in the private international law of each country. There are also international treaties in this area that regulate these issues between the contracting states.

For example, the so-called Lugano Convention, to which all EU states and Switzerland belong, coordinates international jurisdiction between the contracting states.

In addition, depending on the country, various other mandatory legal provisions must be observed, which are motivated by police, religious or moral considerations. In Saudi Arabia, for example, it is forbidden to drink alcohol, wear religious insignia or go out in public as a woman without a headscarf. Failure to comply with such regulations usually results in draconian penalties, ranging from expulsion from the country to imprisonment and corporal punishment. This complex initial situation can make international employee deployment seem like a nightmare and a closed book.

Solution approaches

However, if you are aware of these dangers, the spectre becomes less and less frightening and with structured planning, even the seven seals can be opened.

As a first step, it is important that the international employee assignment is not an end in itself, but rather that the purpose of the assignment is placed in the foreground and the international employee assignment is organised accordingly. In order for this to be implemented, it is first necessary to familiarise oneself with the possible constellations of international employee deployment.

Constellations of international employee deployment

A fundamental distinction must be made here between temporary assignments abroad, permanent assignments abroad and, finally, the recruitment of local staff abroad.

Recruitment of local staff

The last mentioned constellation, the recruitment of local staff, is usually forgotten, although it is basically the cheapest and the easiest to implement. In contrast to the first two constellations mentioned, in this constellation the employee is not transferred from one country to another, but the employee is already working locally in the foreign company and is now entrusted with a new or additional task (the purpose of the international employee assignment), or the employee is recruited locally abroad as a new employee for this purpose. This employee is employed locally under foreign law with an employment contract and remains subject to the local social security system.

There will also be no special problems in terms of residence and tax law, as this is not an international situation with points of contact to other legal systems. This means that only one legal system, namely that of the foreign place of employment, must be observed. Nevertheless, the domestic company will be able to issue instructions to this foreign employee and thus realise the intended purpose. The basis for this right to issue instructions may be a corresponding additional provision in the local employment contract or, for example, a group-wide authorisation regulation.

Differentiation between fixed-term and indefinite assignments abroad

If the purpose of the international employee assignment requires a domestic employee to work abroad for a domestic company, a distinction must be made between a temporary and an indefinite foreign assignment depending on the expected duration of the foreign assignment. For legal reasons, the time limit between the temporary and permanent assignment abroad should be set at 5 years. Most social security agreements, including the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons, provide for the possibility of making posted employees subject to the social security system of the country from which they were posted for a maximum of five years and exempting them from compulsory social security in the country of posting during this period.

In international private law too, temporary assignments abroad, where the employee works for a domestic employer abroad for a limited period, generally enjoy special treatment. It means, during this time the courts at the registered. The last mentioned constellation, the recruitment of local staff, is usually forgotten, although it is basically the cheapest and the easiest to imple-ment.

In contrast to the first two constellations mentioned, in this constellation the employee is not transferred from one country to another, but the employee is already working locally in the foreign company and is now entrusted with a new or additional task (the purpose of the international employee assignment), or the employee is recruited locally abroad as a new employee for this purpose.

Permanent assignment abroad

In the case of a permanent foreign assignment, the connection to the domestic company is less strong than in the case of a temporary foreign assignment due to the time component (i.e. the duration of the foreign assignment). This circumstance generally means that it is either more difficult or no longer possible to subject the employee to domestic social security and generally to domestic law. Rather, in this constellation, the foreign legal system will want to be applied comprehensively in all areas. Against this background, it is then also most sensible and simplest if the employee - if the possibility exists via a foreign group company or similar - is employed locally abroad.

However, it is also possible for the first phase of a foreign assignment - up to a maximum of five years - to be organised and lived in the same way as a fixed-term foreign assignment. This means that the employee remains more closely linked to the domestic company and the country during this initial period and can therefore, for example, remain affiliated to the domestic social security system during this time, which would facilitate an early return. At the end of this period, the separation from the domestic company and the domestic legal system described above would then occur by law.

Temporary assignment abroad with unchanged employer side

The most familiar form of temporary foreign assignment is the posting with an unchanged employer, i.e. the foreign assignment in which the domestic company remains the employer during the temporary period (see figures 1 and 2). The posting is characterised by a special domestic connection, in such a way that the foreign assignment is an exception to the rule in relation to the domestic employment relationship before after the posting. This close domestic connection is also the reason for the special legal treatment described above. Although domestic labour law may continue to apply in principle in this constellation, various mandatory provisions, e.g. of working time and occupational health and safety law, must nevertheless be observed locally abroad which may contradict the otherwise applicable domestic legal system. This generally results in uncertainties and ultimately also potential for conflict. At this point, it is worth recalling the Swiss Posted Workers Act.

It requires foreign employers to comply with Switzerland's binding minimum wage and working time regulations when posting workers to Switzerland, regardless of the law otherwise governing the employment relationship.

In order to enforce these requirements, Switzerland also provides the posted workers concerned with jurisdiction in Switzerland, which takes precedence over any agreement on the place of jurisdiction that deviates from this.

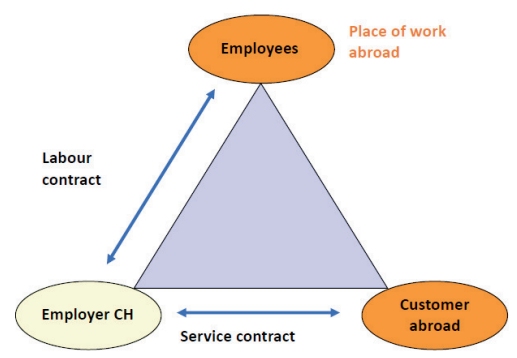

Figure 1: Temporary assignment abroad

Assignment with unchanged employer (without integration)

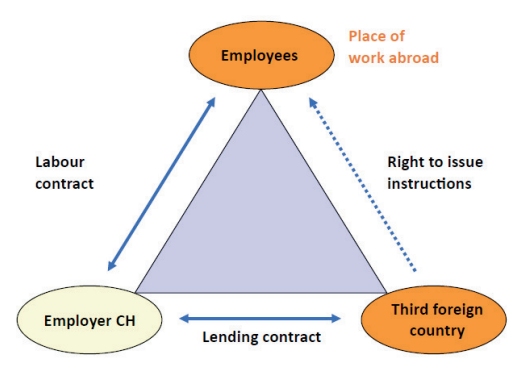

Figure 2: Temporary assignment abroad

Assignment with unchanged employer (with integration)

Temporary assignment abroad with a changed employer

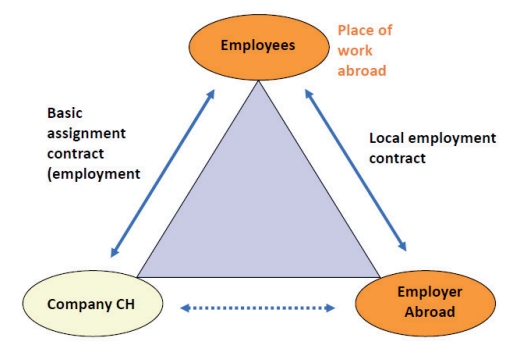

A synchronisation between the applicable law and mandatory provisions at the foreign place of assignment can be achieved by the posted employee concluding an employment contract with the foreign company (e.g. group company) in accordance with foreign law (see figure 3). This is done at the place of assignment for the duration of the posting and maintaining a loose contractual relationship with the posting domestic company in the form of a basic posting agreement.

In principle, the same points are regulated in this basic secondment agreement as in a normal secondment agreement. In addition, however, the local employment contract and the basic secondment contract must contain a provision that coordinates these two contracts with each other. Specifically, this means that the existence of the other contract must be mentioned in advance in both contracts.

It is then advisable to place the provisions of the basic secondment contract hierarchically above those of the local employment contract - insofar as this is possible under local foreign law - and to allow the termination of one contract to automatically lead to the termination of the other. As the basic secondment agreement is not to be regarded as an employment contract due to the lack of organisational integration of the seconded employee in the domestic company, it is subject to full contractual freedom, which of course also allows a free choice of the place of jurisdiction and the applicable legal system. This means that it can be subject to domestic jurisdiction without any problems.

This constellation therefore guarantees maximum legal certainty: The local employment relationship as a whole is subject to local foreign law and the basic secondment contract with the domestic company can be subject to domestic jurisdiction and domestic law without restriction. In principle, this connection with the domestic company will also be sufficient to maintain the domestic social insurance for the posted employee during the foreign assignment.

Figure 3: Temporary assignment abroad

Assignment with local employment contract and basic secondment contract

For the German version, please read here>>

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.