- within Energy and Natural Resources topic(s)

- in United States

- in United States

- within Energy and Natural Resources, Transport and Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

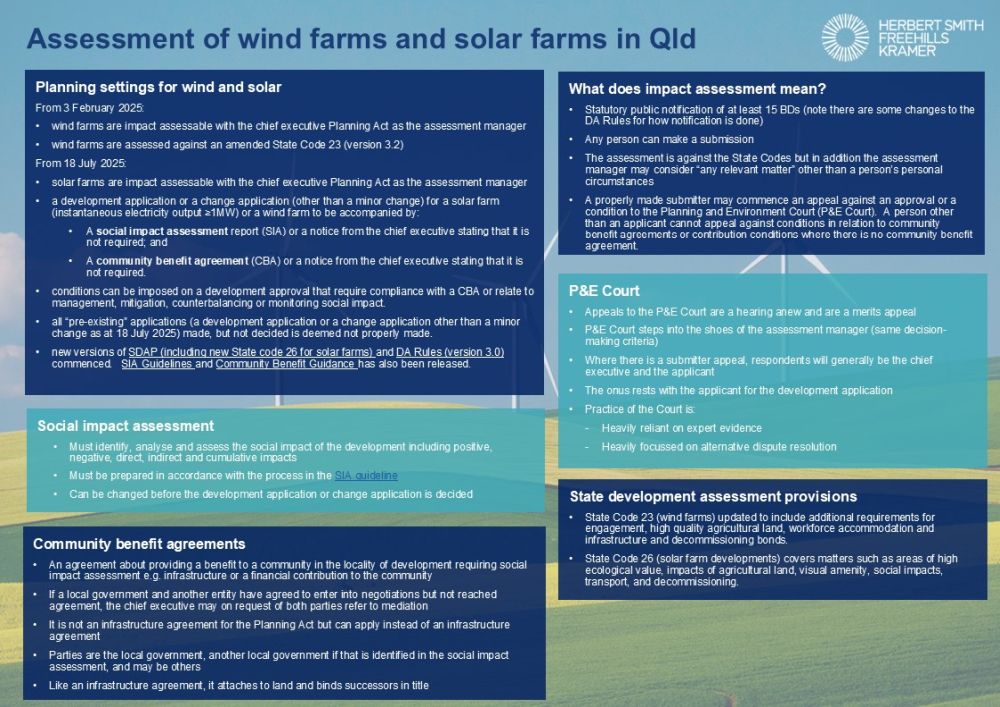

The Queensland Parliament has now passed the Planning (Social Impact and Community Benefit) and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2025 which introduces further legislative reforms impacting the renewable energy industry in Queensland. The amendments commenced on 18 July 2025.

The amendments mean that for development applications for material change of use for a wind farm or a large-scale solar farm (defined as having a maximum instantaneous electricity output of 1MW or more, or being located in a priority development area):

- it is a pre-condition to lodging a development application that a social impact assessment (SIA) has been completed and a community benefits agreement (CBA) has been entered into between the developer and the relevant local government(s) (and potentially others), unless the chief executive gives notice that this is not required. The cost of this is borne wholly by proponents;

- the development application is impact assessable, meaning the application must be publicly notified, the decision making criteria extends to "any relevant matter" and properly made submitters can commence merits appeals in the Planning and Environment Court;

- the assessment manager is the State Assessment Referral Agency (SARA);

- all existing development applications for wind farms and solar farms that have not been decided or called in are declared "not properly made" and will need a SIA and CBA to be relodged, and will be impact assessable. For wind this is inconsequential as no new wind farm applications have been lodged in 2025, and the only applications that have not been decided have been called in. For solar farms, the impact of this amendment is difficult to assess, as these applications were lodged with local government.

A summary of the process for planning assessment for wind and solar projects with the amendments in place can be viewed at the end of this article.

Shifting policy

2025 has seen multiple and rapid shifts in the approvals framework for renewable energy projects in Queensland. These include:

- Paused assessments for wind farms – in January of this year, the Planning Minister directed a pause for four months on the assessment of three wind farms in Queensland. All of those windfarms have now been "unfrozen" and approved, with conditions reflecting the updated planning code (particularly around workforce accommodation and decommissioning bonds).

- Call in and refusal of Moonlight Range – at the same time as issuing the pauses, the Planning Minister "called in" the Moonlight Range wind farm, which had been approved by the chief executive administering the Planning Act 2016 in December of 2024. A call in allows the Minister to reassess and re-decide development approvals, and the Minister has now issued a refusal for Moonlight Range.

- Wind farms became impact assessable and a new State Code was issued – from 3 February 2025, the Planning Regulation 2017 was amended to make all development applications for a material change of use for a wind farm impact assessable development, and at the same time a new State Code 23 (version 3.2) which included updates for workforce accommodation, agricultural land and the introduction of financial bonds for decommissioning was released.

- No new wind farms in the system – there have been no development applications for wind farms lodged so far in 2025. The only two wind farms that have not yet been decided are the subject of a Ministerial call in and are proceeding through the assessment process.

It's hard being green

Before 2025, to have a wind farm or a solar farm approved, a project proponent had to:

- Secure teanure - this requires commercial agreements with the landholders, which included a structure for access, payments, co-use and decommissioning. If the land is subject to native title, a compliance pathway must also be followed.

- Lodge a referral with the Commonwealth Environment Minister to determine if assessment and approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC Act) is required - that goes through at least one public consultation process. Since about 2018, most wind and solar projects have gone through an assessment and approval process under the EPBC Act, which primarily triggers assessment for impacts to species and considers social and economic matters.

- Lodge a development application with the State (for a wind farm) or the relevant local government (for a solar farm) - prior to February 2025, wind farms were code assessable (but are now impact assessable). Wind farms are assessed against State Code 23, which contains requirements for community engagement, species impacts, bird and bat management, erosion and sediment control, traffic management, workforce accommodation, agricultural land, waste management, noise and decommissioning. Solar farms were assessed against the relevant planning scheme.

- Lodge a development application for vegetation clearing, if the project required the clearing of native vegetation at a State level - that application could only be lodged after the relevant Department decided that it was for a "relevant purpose" which requires the applicant to demonstrate that the clearing cannot reasonably be avoided or minimised. This is a pre-condition to lodging a development application. The development application is then assessed against State Code 16, and generally an offset requirement would be imposed after avoidance and mitigation was applied.

- Deal with infrastructure – which generally is done by infrastructure agreements being entered into with impacted local governments, particularly in relation to any road works or infrastructure to support workers accommodation.

- Ensure compliance with the duty of care under the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 or Torres Strait Islander Cultural Heritage Act 2003 (as applicable) - while generally not mandatory, most proponents seek to enter into an approved cultural heritage management plan or cultural heritage management agreement, together with a shared benefits agreement, to discharge this duty;

- Change the Planning Act approval - because the EPBC Act process took significantly longer than the Planning Act approval, and frequently resulted in a reduction in the size of projects or changed technology, proponents often need to do a change application to reconfigure their project to match the EPBC Act approval. This requires a new "relevant purpose" determination for vegetation clearing, and reassessment of changed impacts including offsets.

- Obtain the nested approvals – both the Planning Approvals and the EPBC Act approvals are generally subject to a number of management plans that have to be approved prior to construction commencing and during operation, and require offsets to be legally secured prior to any clearing.

All of these requirements continue unaffected by the legislative amendments.

The same as any industry, projects do not succeed without a social licence to operate. That has long been recognised by the industry, and many "leading practice" guides have been developed led by peak bodies. There will always be a difficulty for social licence with large infrastructure projects – impacts tend to be borne by communities that don't get the most benefits. Recognising this, many renewables projects pay nearby landholders (not just the host landholder), and legacy benefits including for roads, telecommunications and other social benefits at a broader regional level are often part of the deal.

While communities that bear the impacts should benefit from renewables development, a thoughtful and consistent process for benefits should be in place. There is significant upside to coordinating benefit arrangements, and who pays and for what benefits is a complex question. Benefits cost money, and imposing additional costs on generation does not reduce energy costs for consumers.

Queensland's new Energy Roadmap – an opportunity?

The Queensland Government announced in April 2025 that it will prepare a new Energy Roadmap for Queensland. In parallel, the Treasurer and Energy Minister has directed the Queensland Productivity Commission to provide advice on its proposed:

- review of the interim renewable energy targets; and

- development of the five-year energy roadmap "that outlines an affordable, reliable and sustainable energy system".

This includes advice on policy and regulatory barriers impeding efficient private sector investment in new electricity infrastructure, especially generation, storage and firming infrastructure. The Queensland Productivity Commission must provide its advice by 1 September 2025.

The Queensland Budget handed down on 24 June 2025 allocated $5B for Queensland's State owned energy businesses to invest, including in Copperstring, pumped hydro and gas. When the Energy Roadmap was announced, announcements around refurbishment of Tarong and Callide were also made, extending the life of coal-fired generators. The announcements do not include specific measures supporting new wind or solar.

At the same time, the New South Wales budget announced a $2.1 billion investment over 4 years in the Transmission Acceleration Facility and $17.7 million to establish the Investment Delivery Authority to accelerate approvals, including for energy.

In our experience, the following policy settings are crucial to attracting private investment:

- clear signals that a jurisdiction is open for business;

- policy stability;

- an approvals system that is efficient, predictable and certain;

- an approvals system that is competitive and attractive compared to other jurisdictions – it is a competition for investment, and the jurisdiction with the most favourable settings will win.

The Energy Roadmap is a key opportunity for the Queensland government to attract renewable energy investment. In particular, industry will be expecting a plan that provides for land, approvals and connections, and maps out a clear process that delivers policy certainty in Queensland.

We suggest that to develop a system that is efficient, appropriate and transparent, the Energy Roadmap should deliver:

- clear signposts and processes – there should be clear guidance for proponents, that strikes an appropriate balance between open and fulsome community consultation, and manages the consultation fatigue being felt by communities, traditional owners, local governments and businesses;

- identified hubs where renewable energy development will be supported, with appropriate planning settings to direct development towards those areas. Incentives for investment could include regional scale community consultation, consistent cultural heritage management and benefits, coordinated legacy infrastructure upgrades, strategic community benefits and faster delivery. This provides certainty for proponents, removes uncertainty for communities as to where renewables are going to be located, and allows proper cumulative assessment of impacts to biodiversity, agriculture, amenity and community to be completed;

- alignment between the Roadmap and the planning system – the Energy Roadmap should be coordinated with the planning system to ensure its objectives are met. This means considering whether different settings should apply for identified energy hubs (e.g. development in an identified hub is code assessable) and whether separate legislation outside of the planning regime is more appropriate for renewables;

- a clear path to work with the Commonwealth to better coordinate State and Commonwealth assessments (including environmental offsets), to deliver better outcomes in a timely manner;

- ensuring enough is in the system, including by providing for new generation and transmission capacity to be brought online in a timely manner, to both replace aging assets, and accommodate energy growth;

- an energy system that works for Queensland – public ownership in energy infrastructure from generation to distribution is characteristic of the Queensland market which provides an opportunity to reorientate government revenue to new sources, be deliberate in location and benefits, and manage the speed and location of infrastructure.

There is a limited and ever-shrinking window to deliver energy

transition. Now more than ever the Energy Roadmap has some heavy

lifting to do to deliver on the net zero commitment in a way that

is efficient, just and attractive for capital.

This article was written by Kathryn Pacey, Jasmine Wood, Daniel Tweedale and Riley Quinn.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.