- within Finance and Banking topic(s)

- in United States

- within Law Department Performance and Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring topic(s)

Recent amendments to Australia's thin capitalisation rules in Division 820 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (ITAA 1997) to implement new earnings-based tests for general class investors (A&M's summary of the general changes is here 1) have resulted in complexity within the financial services sector, despite the existing thin capitalisation tests for ADIs and financial entities being largely retained. This is especially the case for those entities that are not ADIs or are not eligible exempt special purpose and securitisation vehicles.

In May, the ATO published its guidance priorities 2 on the thin capitalisation amendments, listing high priority and second tier issues. Of note are the following 'second tier' issues:

- The narrowed definition of 'financial entity'

- The expanded definition of 'debt deduction', which now

includes amounts economically equivalent to interest and is

relevant to all taxpayers (including ADIs and financial

entities)

- Interpretation of key debt deduction creation rule (DDCR) concepts, including financial arrangements involving associates and payments/distributions (including dividends and capital returns). The DDCR is relevant to financial entities (but not ADIs or qualifying securitisation entities).

The thin capitalisation amendments came after amendments to Australia's offshore banking unit (OBU) regime. The OBU amendments removed the effective 10 percent concessional tax treatment and withholding tax exemption for interest paid on or after 1 January 2024, but did not repeal the OBU rules in their entirety. Retaining the OBU rules means that the existing thin capitalisation concessions remain for certain eligible entities that operate an OBU (e.g., foreign inbound bank branches applying subdivision 820-E of the ITAA 1997), notwithstanding the recent thin capitalisation changes.

Separately, the ATO is currently considering industry feedback on its discussion paper 3 addressing the attribution of risk-weighted assets to the Australian branch of a foreign bank for thin capitalisation purposes. As noted in Appendix B of the discussion paper, an Australian branch that has a capital shortfall is disallowed a tax deduction for a portion of each of its debt deductions attributable to the branch, unless it relates to its OBU. This is because the branch is not required to hold capital against its Australian assets attributable to its OBU.

In Brief

ADIs and financial entities

- ADIs and entities that qualify as 'financial entities'

can continue to rely on the existing thin capitalisation rules, and

eligible special purpose entities are still exempt. However, the

definition of a 'financial entity' has been narrowed.

Entities that previously relied on registration under Financial

Sector (Collection of Data) Act 2001 (Cth) must now meet

additional criteria to continue to qualify as a 'financial

entity':

- The entity must carry on a business of providing finance, but not predominantly for the purpose of providing finance directly or indirectly to, or on behalf of, the entity's associates; and

- The entity must derive all, or substantially all, of its

profits from that business.

- The arm's length debt test has been replaced by new third-party debt test for financial entities (but not ADIs).

Broadening of 'debt deduction' definition

- The 'debt deduction' definition has expanded beyond

'debt interest' costs to include interest-like costs and

costs that are economically equivalent to interest, and the cost is

not required to be in relation to a 'debt interest'. This

expansion of the definition is relevant for all taxpayers.

- There is a long line of case law in Australia that has

considered the ordinary meaning of 'interest' and its

expanded statutory meaning in subsection 128A (1AB) of the

Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth), which

includes amounts 'in the nature of interest' or 'in

substitution for interest'. The amendments intend to further

broaden the definition by including amounts 'economically

equivalent to interest', an OECD concept not previously used in

the Australian tax law.

- Even though the thin capitalisation asset-based tests for ADIs

and financial entities have remained largely unchanged, the

expansion of the definition of 'debt deduction' means that

other costs such as those associated with swaps are likely to be

captured as debt deductions and could result in additional debt

deduction denial for thinly capitalised entities (even where an

entity relies on the existing rules).

- The broadening of the 'debt deduction' is relevant not only for thin capitalisation rules as the definition of 'debt deduction' is used in other sections of tax law (e.g., section 25-90 of the ITAA 1997 — the future of which is to be subject to further Treasury consideration and hopefully will be subject to wider industry consultation).

Debt Deduction Creation Rule

- The new DDCR applies to financial entities (but not ADIs or

securitisation entities or vehicles) and can deny debt deductions

where related party debt is used to fund specific activities with

related parties, such as the acquisition of CGT assets and making

specified payments — including dividends and capital returns.

The intention of the DDCR is to deny tax deductions for

interest-bearing debt that is 'artificially' created within

a multinational group.

- However, there is no overarching purpose requirement in the

DDCR, which focusses instead on the use of related party debt

funding. This means that tracing of funds will be required.

Further, there is no explicit requirement that the debt is sourced

from within a multinational group. Where the DDCR applies, any

denied debt deductions cannot be carried forward (i.e., it results

in a permanent difference).

- Although securitisation entities and vehicles are exempt from the DDCR (as without this exemption, their ordinary commercial activities could result in debt deduction denial), the application of the DDCR to securitisation entities that are members of a tax consolidated group and the interaction with the single entity rule remains a complex area.

ADIs that operated and maintain an OBU

- The amendments made to the OBU rules did not result in the

repeal of the OBU provisions in their entirety, potentially leaving

the option for a replacement regime. Importantly, the remaining OBU

provisions maintain the concepts of:

- Separately accounting for moneys used in OB activities;

- What constitutes an eligible OB activity; and.

- What is an allowable OB deduction, and assessable OB income.

Interestingly, neither the recent thin capitalisation or OBU amendments removed potential concessions available to inward investing entities (ADIs) whose debt deductions also satisfy the definition of an allowable OB deduction.

A&M's Key Observations

Under the thin capitalisation and OBU rules, as enacted, a key issue for taxpayers in the financial services sector is determining the scope of the application of the new rules, including:

- Where an entity previously relied on registration under the

Financial Sector (Collection of Data) Act 2001 (Cth) to

satisfy the definition of 'financial entity', it must now

also carry on a 'business of providing finance' to satisfy

this definition. This is subjective, and it is unclear whether this

includes more than simply a business of providing debt financing.

For example:

- Will entities engaging in any equity financing and securities-backed lending (including the provision of cash collateral under securities lending and the purchase of securities under repurchase arrangements), asset and receivable financing, invoice financing, debt factoring and broader derivatives trading activities satisfy this requirement?

- Will an entity linked to the provision of finance, such as a

mortgage broker/aggregator, be considered to be in the business of

providing finance by its involvement in the lending process

undertaken by the loan originator?

- Where an entity previously relied on registration under the

Financial Sector (Collection of Data) Act 2001 (Cth) to

satisfy the definition of 'financial entity', it must also

derive all, or 'substantially all', of its profits from

that business of providing finance to satisfy this definition.

Again, there is no bright line threshold for 'substantially

all' of profits, especially for those businesses that derive

income from both the provision of finance and from other sources.

Comfort might be taken from the term being taken to mean

'nearly all' in certain case law precedents. Considering

this further:

- An investment bank may derive income from many sources, including the provision of finance (whether that is through direct lending or securities trading activities) and through the receipt of advisory fees and other commissions from deal-related activity.

- The split of income from multiple sources makes the interpretation of the 'substantially all' requirement dependent on the specific facts and circumstances of the entity or group involved, and the split may vary from year to year.

- Consideration can be given to using proportionate revenue or

profit calculations to evidence the 'substantially all'

requirement. Due to annual fluctuations, averaging over a period

may be more appropriate for your business. While not definitive,

this approach may be reasonable in the absence of specific

rules.

- The amended definition of 'debt deduction' has limited

guidance in the explanatory memorandum. Parliament no doubt expects

that the definition will broadly follow the OECD best practice

guidance for interest limitation rules relating to what is

'interest and amounts economically equivalent to interest'.

In 2015 (further updated in 2016), the OECD published a best

practice framework involving interest deductions 4,

which sets out what is 'interest and economically equivalent to

interest,' taking an economic substance over form approach:

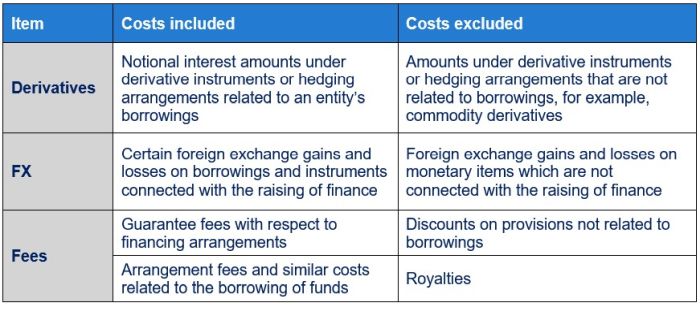

Specific examples referenced in the OECD guidance include:

- Interest on all forms of debt

- Payments economically equivalent to interest

- Expenses incurred in connection with the raising of finance

What you can do now:

- Consider costs that were not previously debt deductions (due to

the previous rules requiring the deduction to arise in respect of a

debt interest) that may now be classified as debt deductions,

resulting in an overall increase to debt deductions. For example, a

receivables financing arrangement may not be a debt interest,

therefore where costs may have previously been interest-like but

not in respect of a tax-law debt interest on issue (for example,

returns on a purchased invoice or receivable), these may now be

considered to be debt deductions under the amended rules, on the

basis they are amounts in the nature of or economically equivalent

to interest.

- All entities (including ADIs and financial entities) should

categorise interest-like costs and run them through their thin

capitalisation modelling to assess downside risk and a worst case

scenario. Although the explanatory memorandum to the bill does not

include any examples of 'interest-like' costs beyond a

generic reference to costs under interest-rate swaps, in line with

the OECD guidance we would expect the expanded definition to

capture certain losses and notional interest amounts on such

derivatives to the extent they are otherwise deductible.

- Maintain clear documentation in determining what costs you are

including in the broadened definition of 'debt deduction'.

Without further guidance we anticipate costs that are included as a

debt deduction will vary amongst taxpayers, and how such costs are

accounted for may impact their inclusion (e.g., net or gross swap

payments).

- Consider the overall facts and circumstances of the

arrangement/scheme in place giving rise to these costs. For

example, what is the relevant scheme to be tested? The definition

of debt deduction 5 includes the

difference between the financial benefits received, or to be

received, by the entity under a scheme giving rise to a debt

interest and the financial benefits provided, or to be provided,

under that scheme. Even under routine interest rate or foreign

currency hedging arrangements, there can be differing views on the

relevant scheme (i.e., is this only the hedged item, or both the

hedged item and hedging instrument considered together) and

therefore what constitutes the 'debt deduction' in such

circumstances. Further, OECD guidance suggests routine foreign

exchange losses which may arise under hedging arrangements (as part

of a debt financing scheme) could meet the expanded definition of

'debt deduction'. But this is not always the case.

- How are such costs incurred by finance businesses and other

businesses undertaking such activities currently accounted for

under Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) requirements?

For example, how are hedging gains and losses characterised and

accounted for under AASB 9 Financial Instruments? Are they brought

to account on a net or gross basis and how does this impact the

calculation of the overall quantum of 'debt deduction'

costs of an entity?

- Consider the residual application of the OBU regime. Whilst there have been no updates from Treasury on a replacement OBU regime, there remain concessions for inward investing entities (ADI) (i.e., foreign inbound bank branches). The thin capitalisation concessions continue to apply for these entities that separately account for "OB moneys" (i.e., money that is non-OB money) and comply with the unrepealed OBU provisions, because any debt deductions for these entities that are also allowable OB deductions are specially excluded in determining the proportion of each relevant debt deduction to be disallowed. The outcome will ultimately depend on where (and how much of this) the foreign bank allocates its equity capital to the Australian branch.

What remains unclear and how can A&M help you navigate these new rules?

- Will you still qualify as a financial entity after considering

the additional requirements; that is, do you 'carry on a

business of providing finance' from which 'substantially

all' of your profits are derived? Objective characteristics,

such as an AFSL for the purposes of providing finance may provide

evidence, but a more subjective view of on the overall profit or

revenue apportionment may be equally important.

- As a result of the broadening of the definition of debt

deduction, how do you determine total debt deductions for the

purpose of the amended thin capitalisation rules?

- Are costs you incur that were previously not debt deductions

now captured as debt deductions? All entities (including ADIs and

financial entities) should ensure all interest-like costs are

categorised and included in their thin capitalisation scenario

modelling to assess downside risk.

- How broadly will the definition of scheme apply in the context

of the new 'debt deductions' definition, and what benefits

are provided or received under that scheme (i.e. does this include

only the hedged item, or both the hedged item and hedging

instrument considered together)?

- Does the manner in which payments or receipts are accounted for

under AASB impact the determination of the debt deductions for thin

capitalisation purposes?

- How should tax return disclosures be appropriately prepared

when an amount is considered to be a 'debt deduction'?

Should an amount that is in the nature of interest or economically

equivalent to interest, and therefore a debt deduction (but not

accounted for as interest under AASB 9), be disclosed at label 6 of

the tax return Form C as an interest expense? Taxpayers should

clearly document the basis of their interest expense disclosures at

label 6 and also their total debt deduction disclosures in their

IDS and be able to explain any differences that may arise.

- Will the term 'amounts economically equivalent to

interest' in due course influence whether interest withholding

tax could apply more widely?

- Are you continuing to maintain separate accounting records for

your OBU and complying with the remaining OBU provisions? If so,

are there any thin capitalisation concessions under the current

rules that may be available to you?

- What documentation have you maintained to support the positions you have adopted with respect to the above issues?

Footnotes

1. Sean Keegan et al., "Earnings-based thin cap rules – state of play," Alvarez & Marsal, April 9, 2024, https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/earnings-based-thin-cap-rules-state-play.

2. Australian Taxation Office, "Amendments to the Thin Capitalisation rules – ATO's PAG consultation topics and prioritisation," May 9, 2024, https://www.ato.gov.au/about-ato/consultation/thin-capitalisation-pag-consultation-summary-and-prioritisation.

3. Australian Taxation Office, "Thin capitalisation – attribution of risk weighted assets to Australian branches of foreign banks" Legal database discussion paper, April 9, 2024, https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/view.htm?docid=%22TDP%2FTDP20241%2FNAT%2FATO%2F00001".

4. OECD, "Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project Limiting Base Erosion Involving Interest Deductions and Other Financial Payments Action 4 – 2016 Update," December 22, 2016, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/limiting-base-erosion-involving-interest-deductions-and-other-financial-payments-action-4-2016-update_9789264268333-en.html.

5. INCOME TAX ASSESSMENT ACT 1997 - SECT 820.40 Meaning of debt deduction (austlii.edu.au)

Originally Published 3 October 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.