- within Tax topic(s)

- in Australia

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy industries

- in Australia

- with readers working within the Property industries

- within Litigation, Mediation & Arbitration, Family and Matrimonial and Strategy topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

On 1 August 2025, the New South Wales Court of Appeal overturned the Supreme Court's earlier decision to relieve Uber of six payroll tax assessments amounting to $81,515,923 and which we covered in an article late last year here. These assessments related to payments Uber received from riders using the Uber app on their phones with a portion of those payments remitted to the drivers that carried on the driving service.

Executive Summary

- This is a significant decision given the implications that it has on the extensive use of contractors by many businesses.

- The fundamental issue to be determined is whether a business is supplying a service to a contractor (no payroll liability to the business) or whether the contractor is supplying services to the business (payroll liability to the business). Here it was determined that the Uber contractors were supplying a service to the business of Uber.

- As such, it is likely that we will see revenue authorities in all States and Territories with similar pieces of legislation to begin to ramp up collecting revenue from businesses with similar structures to Uber.

Background

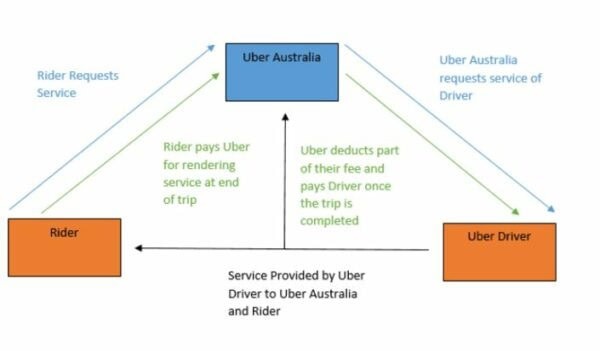

The Uber Driver/Rider service works through two apps, the Driver App and the Rider App, of which drivers and riders can use to connect with each other. Much like a taxi fare, the rider is charged a fare for the provision of the driving service provided by the designated driver on the app. The fare is received by Uber who takes a portion of the fare (20% to 25%) with the rest being passed on to the driver. The below diagram displays how this arrangement works for the parties involved:

As noted in our earlier article, the Chief Commissioner issued payroll tax assessment which amounted to $81 million for the 2015 to 2020 financial years for the amounts remitted back to the drivers.

Decision

Several issues were covered by the Court of Appeal in regard to this decision, however the three main issues may be summarised as follows:

- Whether driving was a service supplied by drivers to Uber

"under" the driver contracts for the purpose of section

32(1)(b) of the Payroll Tax Act 2007 (NSW)

(PTA). The sub issues considered here consisted of

the following:

- Was driving a service supplied to Uber?

- Was the driving service "supplied" under the driving contracts?

- Whether amounts collected by Uber from riders and remitted to drivers are "for or in relation to the performance of work within section 35(1) of the PTA;

- Whether amounts collected by Uber from riders and remitted to drivers are "paid or payable" by Uber within section 35(1) of the PTA.

Issue 1 – Whether Driving was a Service Supplied by Drivers to Uber "under" the Driver Contracts for the purpose of Section 32(1)(b) of the PTA.

Was driving a service supplied to Uber?

Uber contended that their present case was distinguishable with the High Court's decision in Accident Compensation Commission v Odco Pty Ltd [1990] HCA 43 on the basis that Uber was not fulfilling any contract that it had with the passengers to provide a ride. The driving service was supplied to the rider alone. Uber was a mere third party arranging for the ride to take place between the driver and rider. As such, Uber stated they were not getting the driver's service in the same way the agency was in Odco.

Uber also attempted to distinguish their case from Thomas & Naaz where doctors who performed services to patients at medical practices were also held to have provided services to the medical practices in relation to the performance of work. First, Uber stated that the doctors owed the medical practices an obligation to provide the medical services to the patients that attended to the practice. Secondly, the performance of the doctor's duties to the medical practice required "positive actions" by the medical practitioners on a continual basis while the contract was in force (i.e. the doctors were required, under their contract with the medical practice, to provide medical services to the patients, attending the medical centre, adhering to its protocol and taking leave as permitted).

Uber said that the drivers "were not obliged to use Uber's software application for drivers, and if they did so, were not obliged to accept trip requests, nor were they obliged to perform requests once accepted. Put simply, unlike the medical practitioners, there was no "positive action" required on the part of the drivers to perform the driving services and other requirements unlike the medical practitioners in Thomas & Naaz.

The Court of Appeal found that the driving service was indeed supplied to Uber. Central to their reasoning was the reaping of a financial benefit by Uber from the provision of the driving service by the driver to the rider. Put simply, the driving service was a service supplied to Uber as it generated a financial benefit for them, that being in the form of the service fee of 20% to 25% that they collected initially. Our Emphasis:

From Uber's perspective, the exercise of the legal rights described above is not a mere collateral benefit of the contractual relationships it establishes with drivers and riders; it is a (if not primary) purpose of those contractual relationships. Uber's entitlement to exercise those rights depends on the driver's performance of the driving service. Without the provision of such a service, Uber's business could not function. In that sense, drivers clearly "supply" a service to Uber by doing something that is necessary for Uber to derive service fees and to continue its business. That is more than "simply performing an act that assists another" in some sort of Good Samaritan sense. Bearing in mind the purpose of Pt 3, Div 7 of the Payroll Tax Act, the service of driving is plainly a service supplied "to" Uber within the meaning of s32(1)(b).

Was the driving service "supplied" under the driver contracts?

Uber accepted that while having access to the Driver App gave the drivers a chance to "drive for gain" and that this chance stems from the driver contracts, this was merely a practical opportunity and not a legal arrangement between Uber and the driver. The contract merely opened the door for drivers to drive for the riders, it does not legally bind the drivers to drive for Uber. The drivers voluntarily chose to do so out of their own whim, and were not compelled by a contract. For example, Uber compared itself to an internet company which allows users to receive job offers (as a freelancer/contractor) and that this does not mean the internet company is receiving the work the freelancer/contractor does as a result.

The Court found that section 32(1)(b) refers to "a contract under which a person... has supplied to [the person]... service". The word "under" here describes a relationship between two subject-matters, a contract and a supply of services. As such, the necessary question to ask here is when the driver is performing the driving service for the rider, is that service something Uber is getting from the driver as part of that contract.

In considering this, the Court noted that the purpose of Div 7 of the PTA does not provide any reason to construe the word "under" as capturing only services which the contract confers the legal right, or imposes a legal obligation, to perform. This is so given the extended definition of contract in section 31 includes arrangements or undertakings, whether formal or informal and whether express or implied. Hence, the main question to ask here is whether the person supplying the service does so on a similar basis to ordinary employees, with the consideration that casual employees are ordinary employees, but at common law they need not have a contractual right, not a contractual obligation to work at any particular time at all, much like the Uber drivers.

With this in mind, a significant aspect on which employees (including casual employees) supply their services is that it confers on them the right to be paid. In considering the text, context and purpose of Div 7, the Court found that the words, "a contract under which..." in section 32(1) of the PTA extends to a contract:

- which is the source of the right or obligation to supply the services; or

- which expressly refers to, and governs or controls, the supply of the services; or

- which confers a right to be paid for supplying the services.

In applying this construction, in particular with point 2 and 3 above, the Court found that the driver contracts are clearly contracts under which Uber has the driving service supplied to it and that drivers have no reason to perform the driving service except to be paid, and they perform the service in the context of the driver contracts.

Issue 2 – Whether amounts collected by Uber from riders and remitted to drivers are "for or in relation to the performance" of work within section 35(1)

To reiterate, the trial judge found that the payments remitted to the drivers from Uber were not for or in relation to the performance of work. Central to this reasoning was the fact that there was "no element of reciprocity or calibration between the driver and Uber or the rider and Uber with respect to the money paid by the rider." Essentially, those elements only existed between the driver and rider with the conclusion reached that what Uber paid the drivers is in relation to the payment Uber received, not in relation to the work itself.

The Court stated that the trial judge failed to deal with the "nub of the issue" being that they did not consider the nature and strength of the required relationship between the amounts paid or payable on the one hand and the performance of work under the contract on the other. In considering the authorities such as Odco and Smith's Snackfood, the plurality found that the relevant connection be that the services supplied must be work related.

Applying this to the case at hand, the payments made by Uber to the drivers were related to the work performed in transporting the riders. The payments were calculated in regard to the driving service minus the service fee deducted by Uber when they remitted the payment back to the driver. Hence, there is a direct relationship between the provision of the driving services by the drivers and the amounts payable by Uber.

Issue 3 – Whether amounts collected by Uber from riders and remitted to drivers are "paid or payable" by Uber within section 35(1) of the PTA

The Court found that the trial judge erred in finding that there was no connection between the payments made by Uber to the Drivers and the driving service done by the Driver and that Uber operated as a mere payment collection agent.

Uber's initial argument was that the definition of "paid" found in the PTA contemplated the fact that the payment must be quid pro quo. That quid pro quo relationship cannot be found between Uber and the drivers and therefore, "the remitting of that amount by the employer (Uber) to the employee (the Driver) is not part of the employer's payroll, and is not "paid" or "payable" by the employer in the sense used in section 35(1)." Uber merely complied with its obligations to remit to the driver the funds that had been earned by the drivers from riders and merely collected on behalf of the driver.

The Court rejected this argument and found that Uber found no clear reason to depart from Thomas & Naaz and Optical Superstore with the strength of the similarities between these two cases and the facts of this case being fatal to Uber. In assessing these authorities, two points emerged which strongly indicated that payments collected by Uber and remitted back to the drivers were paid/payable by Uber within section 35(1) of the PTA:

- The PTA does not contemplate the flow of money in question and whether that money is beneficially owned by the recipient. There is no limitation on the words "paid or payable" within the PTA that indicates otherwise; and

- The words, "for or in relation to the performance of work" show that there has to be a connection between the funds provided and the performance of work.

Here, the Court said that Uber played a significant role in organising rides and setting dates. The Uber rides are organised through the Uber app with the payments being calculated by Uber itself. Their involvement in the arrangement between the driver's provision of their service to the riders strongly indicated a close degree of connection between the funds provided and the driving service. Additionally, the fact that the drivers beneficially owned part of the money collected by Uber did not dispel the notion that the payments from Uber to the drivers were "paid or payable" by Uber pursuant to the PTA. The similarities of the circumstances of this case to Optical Superstore and Thomas & Naaz, where the employees also beneficially owned the monies, much like how the drivers did, indicated to the Court that there was no reason to depart from the reasoning in those cases.

Implications

- This is a significant decision given the implications that it has on the extensive use of contractors by many businesses.

- The fundamental issue to be determined is whether a business is supplying a service to a contractor (no payroll liability to the business) or whether the contractor is supplying services to the business (payroll liability to the business). Here it was determined that the Uber contractors were supplying a service to the business of Uber.

- As such, it is likely that we will see revenue authorities in all States and Territories with similar pieces of legislation to begin to ramp up collecting revenue from businesses with similar structures to Uber.

- The Court's rejection of the trial judge's reasoning will likely make it easier for State Revenue authorities to consider how their relevant payroll tax acts may apply to similar circumstances, especially in Victoria which shares many similarities with its NSW equivalent.

- As such, business arrangements that are analogous to this case may need to review their arrangements, and also be aware of potential liabilities in payroll and WorkCover that may be assessed to them.

We are happy to review for risk assessment purposes a business you may have concerns in respect of.

Should you wish to discuss the above, please contact Tony Pointon and Andrew Pointon of our Taxation Team.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.