- within Intellectual Property, Immigration and Environment topic(s)

- with readers working within the Environment & Waste Management and Insurance industries

Patent applicants often wish to expand patent protection by filing outside the U.S. This post concerns patent filings stemming from applications previously filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). These applicants can take advantage of a few options – direct filing, filing through the PCT, and regional filings. But, as the second portion of this post will discuss, prior public disclosure of an invention could be an insurmountable hurdle that may prevent applicants from achieving their goals.

International Patent Applications Regimes

The Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Paris Convention) is an international treaty that allows patent applicants to maintain an earlier effective filing date when filing corresponding patent applications outside the country of first filing, so long as the foreign applications are filed within one year of the earliest filing date. Paris Convention applications are filed directly with the Intellectual Property Office of the country of interest.

Most foreign jurisdictions follow strict "absolute novelty" rules that preclude or limit protection after an invention is publically disclosed. Thus, it may be necessary to claim the earlier filing date if the invention has been publicly disclosed or commercialized after the filing date of the U.S. patent application. Again, if the invention was publically disclosed before U.S. filing, foreign protection may be impossible.

Another route that can be used to seek foreign patent coverage is a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application filed with the World Intellectual Property Organization in Geneva Switzerland. U.S. PCT Applicants can file through the USPTO. A PCT application will need to enter the "National Phase" 30-months from the earliest filing date at which time national or regional Intellectual Property offices will complete prosecution. Some Paris Convention countries are not signatories to the PCT, so the only route applicants have available is a direct filing. This map shows the 152 current Contracting States of the PCT.

Some countries are not signatories of the Paris Convention or the PCT (Taiwan, for example), but may offer the possibility of protection if a corresponding patent application is filed within one year of the earliest U.S. filing date.

Entry into the PCT National Phase or direct filing also may include submitting an application to regional patent offices such as the European Patent Office (EPO)1, Eurasian Patent Office (EAPO)2, African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO)3, African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI)4, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)5. Indeed, if one wishes to seek protection in some countries, such as France, the application must first be filed as a regional patent application, in this example an application through the EPO.

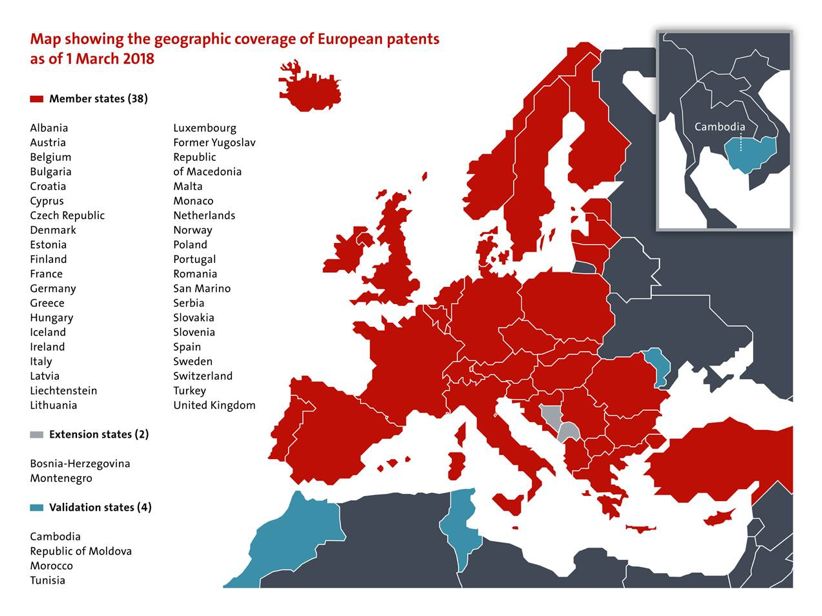

Arguably, filing in the EPO is the most common regional patent system, so it merits some discussion. As shown below, EPO member states generally coincide with the European Union. But it is extremely important to note that the EPO has little to do with the EU. Indeed, non-EU counties such as Norway and, in the future, the UK are members of the EPO. In the latter's case, Brexit should have little effect on the UK's standing in the EPO.

Like the other regional filing regimes, the EPO offers centralized patent applicant examination and has promised one day to provide a unified patent court system. After the EPO grants an application, it must be validated in one or more of the member states.

Novelty & Public Disclosure Grace Periods

Novelty is a basic principle for determining the patentability of an invention. That is, for an invention to be patent-eligible, it must be "novel" and, thus, not in the public domain. Therefore, it is prudent for patent applicants not to publically disclose their invention before filing a patent application describing the invention.

In practice, however, inventors publically disclose their inventions before filing a patent application inadvertently or purposely 1) during the research, development, or trial stage; 2) while attempting to secure funding; 3) through marketing or advertising; or 4) by public display, use, or commercial sale. Fortunately, the United States patent laws are quite liberal relative to the rest of the world and provide a one-year grace period that allows inventors to apply for patent protection within one-year from the date of first disclosure, sale, or use.

As highlighted below, novelty requirements differ greatly between countries. In many countries, public disclosure of the invention by any person, including the inventor, before the filing of a patent application destroys novelty and, thus, the ability to obtain a valid patent. These countries are said to operate under an "absolute novelty" regime.

In other countries, a 6 or 12-month grace period is provided that is somewhat more stringent than the grace period the United States provides. More specifically, some grace periods can be viewed as defensive as they allow inventors to seek patent protection after an unauthorized third-party public disclosure.

Other grace-periods account for common academic and research practices, by allowing patent protection after public disclosure so long as it was in the form of a recognized scientific publication or at a scientific exhibition. For example, the EPO provides no grace period except for a six-month period in instances of unauthorized disclosure or under circumstances of public display in an official international exhibition. In some countries the geographic location of the disclosure is relevant, wherein disclosure outside the jurisdiction is not novelty-destroying.

Foreign grace periods are especially relevant if an applicant has taken advantage of the U.S. grace period and filed an application after public disclosure. In many instances, that applicant may be precluded from obtaining patent protection in many countries, because the later-filed foreign application(s) would have an effective filing date that occurred after the date of first public disclosure. As such, issues frequently arise when inventors seek global patent protection, which is why so many practitioners advise would-be patent applicants to file before the invention is publically disclosed.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has provided a table comparing the novelty requirements around the world after public disclosure, use, or sale.We have recreated a trimmed down version of this table. For brevity's sake, we have excluded many of the country-specific criteria in the WIPO table, for example, how the disclosure must be made, by whom, and to what audience. This table is not offered as legal advice. Patent practitioners should always consult the applicable foreign patent laws for additional information.

Tips for Navigating Foreign Patent Law

So what happens when an invention has been publically disclosed before a patent application has been filed? All may not be lost. Here are some helpful tips in navigating the quagmire of foreign patent laws regarding novelty after public disclosure, use or sale.

- File a PCT application within six-months of the first disclosure, sale, or use. A PCT application is commonly used for international protection of inventions and sets an international filing date in many foreign countries. By filing a PCT application within six-months of the first disclosure, sale, or use, an inventor may not be precluded from seeking protection in countries that have shorter 6-month grace periods regarding novelty (assuming the inventor also satisfies any additional country specific requirements).

- Do not wait an entire year to file a PCT or foreign patent application once you have filed a provisional application in the United States after the first disclosure, sale, or use. This provisional application procedure is commonly used in the United States because it complies with U.S. patent laws. However, it may be a big mistake when seeking foreign patent protection where a prior public disclosure has been made. Most countries do not count the filing of a United States provisional application as the priority date for international filings. Rather, foreign countries typically require filing in their specific country, such as through a PCT application. Therefore, in circumstances of prior disclosure, use, or sale, an inventor who first files a provisional application and then waits the allowable one-year period to file a PCT application will likely be precluded from obtaining any foreign protection of his or her invention.

- Whenever possible, make a public disclosure under a confidentiality or non-disclosure agreement. In many countries, a confidential disclosure does not constitute an activity that bars patentability. Confidential disclosures refer to any disclosure made with an understanding or expectation of confidentiality, or under a written or express agreement or confidentiality or non-disclosure. Thus, for an inventor considering foreign filing, a confidential disclosure should not be the cause for abandoning foreign patent protection.

As anyone can see, filing patent applications outside the United States can be complex, so it is prudent to discuss each situation with competent counsel. Visit Lewis Brisbois' Intellectual Property & Technology Practice page to find an attorney in your area who can help.

This is the first in a series of posts on foreign filing. Future posts will cover such topics as: design protection outside the U.S. foreign filing costs considerations; other forms of patent protection available outside the U.S. (i.e. Utility Models); expediting foreign patent prosecution under the Patent Prosecution Highway; and the European Unified Patent Court.

Footnotes

1 Protection possible in the following countries after grant and validation: Belgium, Cyprus, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Monaco, Malta, Netherlands, Slovenia, Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Czechia, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, United Kingdom, Croatia, Hungary, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Sweden, Slovakia, San Marino, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina , Montenegro , Morocco, and the Republic of Moldova.

2 Protection possible in the following countries after grant and validation: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan.

3 Botswana, Ghana, Gambia, Kenya, Liberia, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Sudan, Sierra Leone, Sao Tome and Principe, United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

4 Burkina Faso, Benin, Central African Republic, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Cameroon, Gabon, Guinea, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Comoros, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Chad, and Togo.

5 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Sultanate of Oman and Bahrain.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.