This is part of a series of articles discussing recent orders of interest issued in patent cases by the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

In Cozy, Inc. v. Dorel Juvenile Group, Inc., No. 21-cv-10134, Magistrate Judge Dein granted Dorel's motion for default judgment as to Cozy's affirmative infringement claims and dismissed the Complaint with prejudice. The Court took Dorel's motion under advisement as to its counterclaims.

Plaintiff's counsel withdrew and, despite repeated reminders that corporate litigants cannot be unrepresented, it failed to obtain new counsel for all purposes. The Court found that without counsel Plaintiff was left unable to prosecute its claims, which must therefore be dismissed.

In addition, despite being allowed multiple opportunities to amend its contentions, Plaintiff failed to clearly identify the allegedly infringing products as well as to map them to each limitation of the asserted claims until its expert report. That report was ultimately stricken for asserting a new infringement theory. Plaintiff was granted the opportunity to submit a revised report but did not do so, and thus had no expert to testify on the issue of infringement. In view of the complicated nature of the asserted patents, the Court found the lack of an expert fatal to Plaintiff's case.

The Court also noted that its prior findings regarding the priority dates of two asserted patents rendered accused products prior art, and that Defendant provided credible and unrebutted evidence that its products do not satisfy certain claim limitations of the remaining products.

Accordingly, the Court found that, while a severe result, the facts at bar warranted dismissal of the complaint with prejudice.

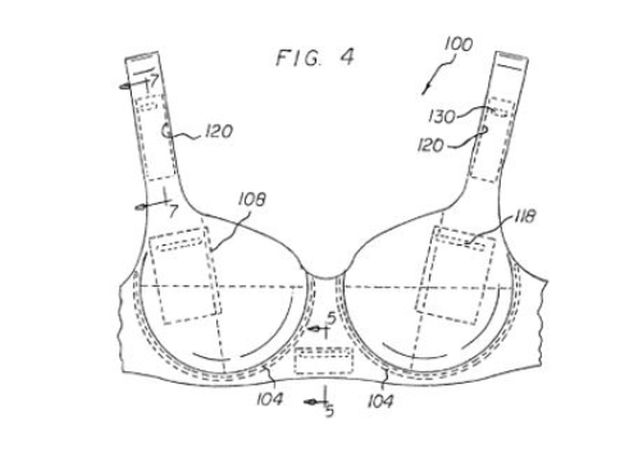

In SherryWear, LLC v. Nike, Inc., No. 23-11599, Judge Sorokin construed three terms appearing in Plaintiff's eight asserted patents related to brassieres. In each instance, Plaintiff proposed a broader construction than Defendant, and in each instance the Court agreed with Defendant.

"A pocketed bra assembly comprising . . . a left cup and a right cup, each cup being an area to receive a breast of a wearer and having inside and outside surfaces"

| Plaintiff | Defendant / Construction |

|---|---|

|

A pocket bra assembly including a left cup and a right cup whereby the cups are not necessarily separate and distinct from one another. |

"a bra with two distinct cups: a 'left cup' and a 'right cup.'" |

The Parties' dispute about this term centered on the phrase "a left cup and a right cup," with Defendant contending that distinct cups are required and Plaintiff in disagreement. The Court sided with Defendant, observing that whether a product ultimately contains "cups" is a question of fact.

The Court looked to the claims, observing that they use the phrase "each cup" (emphasis by the Court), indicating that the cups are distinct. The Court next observed that both the specification and the figures depict two distinct cups, finding that the plain meaning in view of the intrinsic record requires that the cups be distinct.

The Court also noted that Plaintiff provided no basis to conclude otherwise and rejected the notion that the construction adopted by the Court was based on lexicography or disavowal rather than an analysis of the intrinsic record. The Court also found that Plaintiff's proposal would lead to absurd results, as under that proposal any form-fitting garment covering the chest would satisfy this limitation. Reiterating that Plaintiff provided no support for its view, the Could rejected it.

The Court therefore adopted Defendant's construction.

"chest strap"

| Plaintiff | Defendant / Construction |

|---|---|

|

"the entire fabric running along the chest and side of the user extending to the back of the user; not limited to the band at [the] bottom of a bra." |

"a strap that is connected to the cups and goes around the chest." |

The Court found that Plaintiff's proposed construction was overbroad, observing that it could be read to encompass the entire bra, and was unsupported by the intrinsic evidence.

The Court found that Defendant's construction (with a small adjustment to accommodate the wording of one asserted patent) was supported by the intrinsic evidence, which point Plaintiff did not dispute. More specifically, the Court held that the term is merely the combination of the commonly understood words "chest" and "strap," and when read in the context of the claims and specification is connected to the cups or bra portion, depending on the embodiment at issue.

The Court therefore adopted Defendant's construction (with one modification).

"a central patch attached intermediate to the left and right cups"

| Plaintiff | Defendant / Construction |

|---|---|

|

"a patch located between the left and right[] cups which may sit below, above, or level with the cups." |

"a patch attached at least partially between the two cups, but not entirely above the top edges of the cups or entirely below the bottom edges of the cups." |

The Parties' dispute centered on whether the term "intermediate" carries upper and lower bounds on the location of the patch. The Court found that "[i]nherent in the term itself, as confirmed by the patent (for example, in Figure 4) and the cited definitions, is a sense of proximity tying the 'intermediate' thing to the "extremes" on either side of it," and repeated Defendant's observation at the hearing that a layperson standing upright would not describe their head as intermediate to their feet.

The Court rejected Plaintiff's proposed construction, finding that even the figure Plaintiff focused on as supposed intrinsic evidence shows the patch located at least partially between the top and bottom of the cups:

The Court therefore adopted Defendant's construction.

In Mobile Pixels, Inc. v. The Partnerships and Unincorporated Associations Identified on Schedule "A", No. 23-cv-12587, Judge Burroughs denied a motion from two named defendants to dismiss Mobile Pixels' design patent infringement claims against them under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6).

Mobile Pixels' asserted design patent covers an ornamental design for a monitor that extends from a laptop or computer screen. Noting that "[d]ismissal is appropriate where no ordinary observer could determine that the two designs are substantially the same," the Court observed that the "Patent depicts a rectangular screen extending from a laptop monitor . . .and the images of the Defendants' product depict a rectangular screen that does the same."

The Court further noted: "that the designs are not identical is not . . . dispositive . . . because a finding of infringement requires only that the accused design and the patented design be 'substantially the same.'" The Court therefore declined to dismiss Mobile Pixels' design patent claims because it was unpersuaded that no ordinary observer could determine that the two designs are substantially the same.

Also in Mobile Pixels, Inc. v. The Partnerships and Unincorporated Associations Identified on Schedule "A", No. 23-cv-12587, Judge Burroughs granted Plaintiff Mobile Pixels' motion to strike an affirmative defense and dismiss certain counterclaims without prejudice. The struck affirmative defense and dismissed counterclaims included inequitable conduct before the USPTO, declaratory judgment of invalidity, tortious interference with contractual relations, tortious interference with prospective advantageous business relations, trade libel and injurious falsehood, unjust enrichment/restitution, violation of M.G.L. Ch. 93A, and attempted monopolization under 15 U.S.C. § 2. Mobile Pixels had already been granted a temporary restraining order (TRO) by the Court in this case, which gave rise to several of Defendants' counterclaims.

The Court first found "Defendants [] failed to identify any of the who, what, when, where, and how" necessary to plead inequitable conduct, and therefore struck Defendants' inequitable conduct affirmative defense.

Moving to the counterclaims, the Court dismissed Defendants' invalidity counterclaim for failing to identify facts supporting the claim of invalidity, and declined Defendants' invitation to consider allegedly supporting documents outside of the pleadings.

The Court then dismissed counterclaims for tortious interference with contractual relations, tortious interference with prospective advantageous business relations, trade libel and injurious falsehood, and unjust enrichment/restitution, that all derived from Mobile Pixels' providing the TRO obtained at the outset of the litigation to Amazon, the common marketplace for both Mobile Pixels' and the Defendants' products. Specifically, the Court found that Mobile Pixels' conduct was protected by the litigation privilege, which covers "statements by a party, counsel or witness in the institution of, or during the course of, a judicial proceeding . . . provided such statements relate to that proceeding" and which applies "regardless of malice, bad faith, or any nefarious motives . . . so long as the conduct complained of has some relation to the litigation." The Court therefore ruled that Mobile Pixels' statements and conduct with respect to Amazon regarding the TRO obtained from the Court were subject to the litigation privilege and could not support the struck counterclaims.

The Court also struck Defendants M.G.L. Ch. 93A unfair competition counterclaim and the counterclaim for attempted monopolization under 15 U.S.C. § 2, which both alleged that the lawsuit is baseless. Mobile Pixels argued (and the Court agreed) that its conduct in filing the complaint and obtaining a TRO was protected by the Noerr-Pennington doctrine, which grants a plaintiff "immunity from allegations of unfair competition when bringing a lawsuit unless that lawsuit is a 'sham.'" The Court considered Defendants' arguments for a "sham" litigation—including allegedly copying allegations from another suit and an alleged failure of pre-suit investigation by Mobile Pixels—but found that those allegations as pled could not support Defendants' Chapter 93A counterclaim.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.