Holding

In Allele Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., 20-CV-08255 (SDNY Dec. 5, 2022), the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York construed four disputed terms "isolated," "monomeric or dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein," "monomeric polypeptide," and "non-naturally occurring" in favor of Plaintiff Allele.

Background

Allele Biotechnology ("Allele") is the patent holder of U.S. Patent No. 10,221,221 ("the '221 Patent"), which is titled "Monomeric Yellow-Green Fluorescent Protein from Cephalochordate." The '221 Patent is directed to novel green/yellow fluorescent proteins derived by protein engineering based on an exemplary wild-type tetrameric yellow fluorescent protein from Branchiostoma lanceolatum ("LanYFP"), a marine invertebrate of the cephalochordate subphylum. Allele Biotechnology, at *1.

Allele alleged that Regeneron infringed five claims of the '221 Patent, set forth below, all of which contain at least one of the disputed terms and are therefore relevant to the instant claim construction:

Claim 1: A non-naturally occurring isolated monomeric or dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein comprising a polypeptide having at least 95% sequence identity to the amino acid sequence of SEQ ID NO: 1, wherein the protein comprises at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: F15I, R25Q, A45D, Q56H, F67Y, K79V, Sl00V, F115A, I118K, V140R, T141S, M143K, L144T, D156K, T158S, S163N, Q168R, V171A, N174T, I185Y, and F192Y;

Claim 2: The non-naturally occurring LanYFP fluorescent protein of claim 1, wherein the protein is a monomer;

Claim 3: An isolated non-naturally occurring monomeric polypeptide encoded by a nucleic acid having at least 90% sequence identity to SEQ ID NO: 2 SEQ ID. No. 2, where the nucleotide sequence encodes for a polypeptide which comprises at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: Il 1 SK or Nl 7 4 T, at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: V140R, L144T, D156K, T158S, Q168R, and F192Y, and at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: R25Q, A45D, S163N, F151, Q56H, F67Y, K79V, Sl00V, F115A, T141S, M143K, V171A, and 1185Y;

Claim 4: The non-naturally occurring isolated monomeric or dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein of claim 1, wherein the protein comprises at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: Il 1 SK and Nl 7 4 T, at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: V140R, L144T, D156K, T158S, Q168R, and F192Y, and at least one mutation selected from the group consisting of: R25Q, A45D, S163N, F151, Q56H, F67Y, K79V, Sl00V, F115A, T141S, M143K, V171A, and I185Y; and

Claim 5: The non-naturally occurring isolated monomeric or dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein of any of claim 1, 3 or 4, wherein the protein comprises a polypeptide having at least 97% sequence identity to the amino acid sequence of SEQ ID NO: 1.

District Court Decision

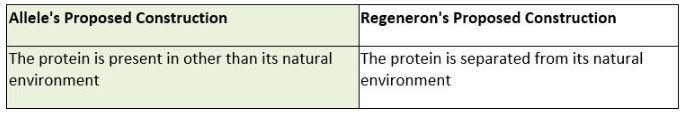

1. "Isolated" (Claims 1, 3, 4, and 5)

First, the parties presented different proposed constructions for the term "isolated," disputing if the fluorescent protein was required to be affirmatively separated from the cell in which it was expressed. Id. at *6. Allele's proposed construction does not require an affirmative separation, but rather just requires that the protein is present in other than its natural environment. Id. Allele based this construction on the fact "that the specification is replete with embodiments that describe fluorescent proteins not separated from the cell in which they were expressed, or purified, as part of the invention." Id. On the other hand, the Defendant, Regeneron, argued that based on the prosecution history, an affirmative step separating the protein from its natural environment is necessary. Regeneron argued that the "prosecution history reflects that the examiner understood the term 'isolated' to mean separated because the examiner stated that an isolated protein 'can be made by . . . synthetic peptide synthesis or purification from the natural source.'"

In Oatey Co. v. IPS Corp. the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit explained that "where claims can reasonably [be] interpreted to include a specific embodiment, it is incorrect to construe the claims to exclude that embodiment, absent probative evidence [to] the contrary." 514 F.3d 1271, 1277 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Here, the district court found it was reasonable that the claims could be interpreted to include embodiments where the protein was not affirmatively separated. The patent examiner stated that a protein theoretically could be purified, which is not probative as to whether the term requires the affirmative step of separation. Accordingly, the district court agreed with Allele and construed "isolated" to mean "the protein is present in other than its natural environment." Allele Biotech. at *6.

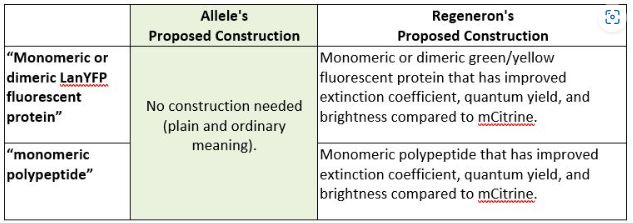

2. "Monomeric or dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein" (Claims 1, 4, and 5) and "monomeric polypeptide" (Claim 3)

Next, the parties presented different proposed constructions for the phrases "monomeric or dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein" and "monomeric polypeptide." Allele proposed that these phrases need not be construed and should be given their plain and ordinary meaning, while Regeneron argued that Allele disavowed the full scope of the claim during prosecution such that additional limitations should be read into the claims. In connection with this argument, Regeneron pointed "to three statements Plaintiff made to the examiner over the course of a four-year period regarding the properties of the claimed invention." Id. at *7.

Each of these three statements, however, was made in response to the examiner's rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 101 for ineligible subject matter. "These statements were made as part of a broader discussion between the examiner and Plaintiff on whether the patent sufficiently distinguished the claimed invention from its naturally occurring counterpart." Id. In none of the statements did the Plaintiff claim that the invention has superior fluorescent properties over the prior art, rather the Plaintiff simply explained how its invention was different from naturally occurring tetrameric LanYFP protein. Id.

In its analysis, the district court first explained that Regeneron neither argued that the plain and ordinary meaning of these two phrases is disputed nor argued that these phrases are ambiguous in any way. Id. at *7-8. When the plain and ordinary meaning is undisputed, a district court may properly decline to construe such a claim. ActiveVideo Networks, Inc. v. Verizon Commc'ns, Inc., 694 F.3d 1312, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (holding that a district court "did not err in concluding that these terms have plain meanings that do not require additional construction" and further noting that it would be erroneous to "read[] limitations" into such undisputed claims).

The district court then explained that regardless of this lack of dispute, Regeneron failed to meet its burden to show disavowal of claim scope. Id. at *8. To prove that Allele disavowed the claim scope, Regeneron would have had to show that Allele evinced a "clear and unmistakable surrender of claim scope." Aylus Networks, Inc. v. Apple Inc., 856 F.3d 1353, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The standards for finding disavowal are "exacting" as "the specification or prosecution history [must] make clear that the invention does not include a particular feature." GE Lighting Sols., LLC v. AgiLight, Inc., 750 F.3d 1304, 1309 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

For both reasons explained above, the district court declined to construe the terms "monomeric dimeric LanYFP fluorescent protein" and "monomeric polypeptide." Id.

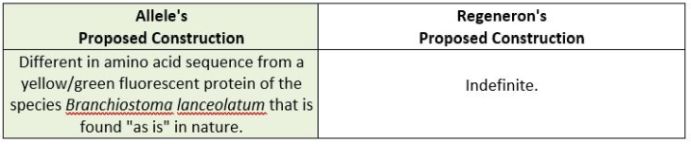

3. "Non-Naturally Occurring" (Claims 1-5)

Finally, the parties proposed different constructions for the phrase "non-naturally occurring"—more specifically, Regeneron argued that this phrase was indefinite.

Definiteness is determined from the point of view of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of filing and is resolved with reference to the patent's specification and prosecution history. Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. 898, 908, 134 S. Ct. 2120, 189 L. Ed. 2d 37 (2014). "The definiteness requirement, so understood, mandates clarity, while recognizing that absolute precision is unattainable." Nautilus, 572 U.S. at 910 (emphasis added). Instead, "the certainty which the law requires in patents is not greater than is reasonable, having regard to their subject-matter." Id.

Defendant's primary argument in support of its proposed construction is that "no person of ordinary skill in the art can be certain if a fluorescent protein is not found in nature because new naturally occurring proteins are still being discovered." Allele Biotech. at *9. This was not enough, however, to render the term indefinite. The district court pointed out that "[t]he parties agree that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be able to determine whether a protein is naturally occurring by comparing that sequence to a widely used database maintained by the National Institutes of Health known as 'GenBank.'" Id.

Additionally, the district court cited portions of the specification that supported Plaintiff's proposed construction, along with the prosecution history of the patent. For example, during prosecution Plaintiff amended its claims to include the phrase "non-naturally occurring" in response to the PTO's rejection and explained to the examiner that the amino acid sequence of the claimed invention was different from the protein that is found "as is" in nature. Id. at *9-10.

Accordingly, the district court found the phrase not indefinite and construed "non-naturally occurring" as meaning "different in amino acid sequence from a yellow/green fluorescent protein of the species Branchiostoma lanceolatum that is found 'as is' in nature."

Takeaways

- Claim construction is an important phase of any patent case. The more care a practitioner takes throughout drafting and prosecution, the better the likelihood the patent claims will be construed in favor of the patentee, and the better the likelihood the patent will withstand challenges by opponents.

- Where claims can be interpreted to include a specific embodiment, it is generally incorrect to construe the claims to exclude that embodiment, absent probative evidence to the contrary. During prosecution (or litigation), be on the lookout for arguments and proposed constructions that attempt to exclude specific embodiments.

- A district court can decide to not construe a term if the parties agree on its plain and ordinary meaning.

- The standard for showing that claim scope was disavowed is a "clear and unmistakable surrender of claim scope."

- "[S]ome modicum of uncertainty" may be allowed in assessing a term's definiteness. Nautilus, 572 U.S. at 899.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.