The extent to which certain apportionment principles, such as the entire market value rule and related doctrines, may constrain damages theories in patent infringement cases remains uncertain. This article reviews the current state of apportionment law through the lens of semiconductors and electronic components-ideal archetypes for such issues-and proposes a framework to help reconcile governing precedents that, at times, seem to conflict.

Introduction

We often define the state of human civilization by the materials we use to make tools-the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, and so on. It seems reasonable to say that we live in the Semiconductor Age. Essentially everything in the modern world relies in some way on semiconductor technologies and electronic components. They dominate not just our smartphones, tablets, and computers, but also our cars, home appliances, and even light bulbs. Even the most innocuous household items depend on them. Modern products are often designed using computers, constructed with the aid of digitally managed processes, ordered over the Internet, and tracked and shipped using digital logistics networks. All of these tasks depend on semiconductors and electronic components, and our collective reliance on those technologies seems unlikely to abate any time soon. The automobile industry cannot even manufacture certain vehicles right now simply because semiconductor chips are in short supply.1

The sheer ubiquity of semiconductor technologies means companies from automobile manufacturers2 to retailers3-not just electronic device designers and semiconductor foundries-will continue to be potential targets for semiconductor-related patent infringement lawsuits. But, despite their ubiquity, semiconductor technologies often hide behind the scenes in tiny features of what consumers and businesses actually buy, sell, and use. Most people never see or think about them, which is why semiconductor technologies and electronic components are often the tip of the spear for patent damages law.

A patent may only improve one aspect of an accused device that might include hundreds, if not thousands, of other valuable additions. This implicates a concept called "apportionment," intended to reflect the long-standing principle that a patent's value should not exceed its relative contribution to the value of a product. Because apportionment is often an important issue in cases involving semiconductors and electronic components, they provide the basis for much of the Federal Circuit's governing law about apportionment.

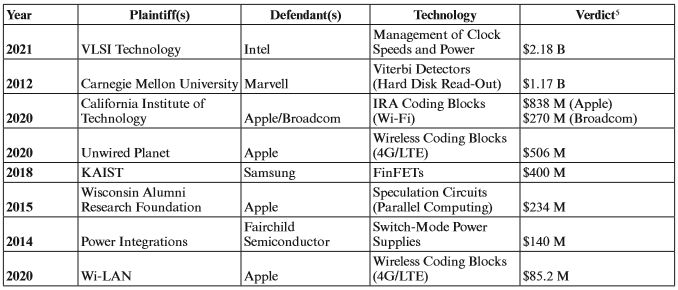

Patent lawsuits involving semiconductors and electronic components can also lead to large damages awards simply because semiconductor technology is so ubiquitous.4 The chart on the next page illustrates the point, showing some of the most eye-catching damages awards from cases decided in the last several years, including a recent $2.18 billion verdict against Intel.

Entire Market Value Rule (EMVR)

In most patent cases, the damages inquiry centers on what constitutes a "reasonable royalty."6 Such a royalty typically includes two components: (1) a royalty base, which defines the value of units for which damages are assessed; and (2) a royalty rate, which defines the relative value of the claimed invention per unit. The total royalty is the product of the base and the rate, accounting for product volumes and time. Any reasonable royalty determined through litigation must account for apportionment.

Discussions of apportionment often invoke Garretson v. Clark, a terse Supreme Court decision authored by Justice Field in 1884 that consists of just two paragraphs.

The invention at issue related to a replacement mop head, and the patentee improperly sought to recover damages based on the value of the entire mop. Quoting the trial court, the Supreme Court stated:

The patentee . . . must in every case give evidence tending to separate or apportion the defendant's profits and the patentee's damages between the patented feature and the unpatented features, and such evidence must be reliable and tangible, and not conjectural or speculative; or he must show, by equally reliable and satisfactory evidence, that the profits and damages are to be calculated on the whole machine, for the reason that the entire value of the whole machine, as a marketable article, is properly and legally attributable to the patented feature.7

This appears to be the first articulation of an apportionment principle called the "entire market value rule" (EMVR).8 Put more succinctly, the EMVR says a patented feature of a component should not be tied to the value of a multi-component article unless the patented feature drives demand for the article as a whole.9 This is typically difficult to show, especially for semiconductor technologies and electronic components. It is not enough that consumers would prefer the accused product to include the patented feature or even that removing the patented feature would create an undesirable or inoperable product. Rather, the EMVR exception applies only when the patented feature itself prompts consumers to buy the product.10 Patented aspects of certain products, like pharmaceuticals, may be able to clear that hurdle more easily. A person buying a patented drug composition, for example, may be buying that drug precisely because of its patented composition. In many other products, however, patented features can be farther removed from purchasing decisions. Patented quantumwell structures used in LEDs or error-correction protocols used in wireless communications, for example, might not be at the top of consumers' minds when purchasing a light bulb or smartphone. In such circumstances, the EMVR may preclude relying on the value of the entire product as a royalty base.

Smallest Salable Patent-Practicing Unit (SSPPU) and Its Limitations

Although the EMVR does not say what royalty base to use (only which one not to use), a concept called the smallest salable patent-practicing unit (SSPPU) sheds some light on this issue. Sitting by designation, the former Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit presided over a trial involving a patented way of issuing instructions in a microprocessor. Instead of using the value of the accused computer product as the royalty base, which had "significant non-infringing components," he noted, "The logical and readily available alternative was the smallest salable infringing unit with close relation to the claimed invention-namely, the processor itself."11 The Federal Circuit later endorsed this idea of the SSPPU, calling the EMVR a "narrow exception":

Where small elements of multi-component products are accused of infringement, calculating a royalty on the entire product carries a considerable risk that the patentee will be improperly compensated for non-infringing components of that product. Thus, it is generally required that royalties be based not Year on the entire product, but instead on the "smallest salable patent-practicing unit." The entire market value rule is a narrow exception to this general rule.12

Footnotes

1 See, e.g., Jonathan M. Gitlin, A Silicon Shortage Is Causing Big Issues for Automakers, Wired (Feb. 7, 2021), available at https://www.wired.com/story/ silicon-chip-shortage-automakers/ ("[I]t's getting so bad that a number of OEMs . . . have had to go as far as idling shifts and even entire factories.").

2 See, e.g., Complaint, Advanced Silicon Technologies, LLC v. Volkswagen AG, Case No. 1:15-cv-01181 (D. Del. Dec. 21, 2015), ECF No. 1 (accusing Volkswagen and Audi of infringing patents directed to graphics processor circuit architectures).

3 See, e.g., Complaint, Seoul Semiconductor Co. v. Bed Bath & Beyond, Inc., Case No. 2:18-cv-03837 (C.D. Ca. May 8, 2018), ECF No. 1 (accusing Bed Bath & Beyond of infringing patents directed to LEDs and LED packages, including "epitaxially produced quantum dot semiconductor components").

4 See, e.g., Scott Graham, How Irell's Morgan Chu Is "Spoon-Feeding" a Billion-Dollar Damages Case to Jurors, The AmLaw Litigation Daily (Feb. 22, 2021) (noting that "even a 1% royalty could cost Intel billions of dollars" because it has sold so many microprocessors).

5 See Jury Verdict Form, VLSI Tech. LLC v. Intel Corp., Case No. 6:21-cv00057-ADA (W.D. Tex. Mar. 2, 2021), ECF No. 564; Verdict Form, Carnegie Mellon Univ. v. Marvell Tech. Grp., Ltd., Civil Action No. 09-290 (W.D. Pa. Dec. 26, 2012), ECF No. 762; Jury Verdict, Cal. Inst. of Tech. v. Broadcom Ltd., Case No. CV 16-3714-GW-AGRx, (C.D. Cal. Jan. 29, 2020), ECF No. 2114; Verdict Form,Optis Wireless Tech., LLC v. Apple Inc., Civil Action No. 2:19-cv-00066-JRG (E.D. Tex. Aug. 11, 2020), ECF. No. 483; Verdict Form, KAIST IP US LLC v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd., Case No. 2:16-cv01314-JRG-RSP (E.D. Tex. June 15, 2018), ECF. No. 481; Special Verdict - Damages, Wis. Alumni Research Found. v. Apple, Inc., No. 14-cv-062-wmc (W.D. Wis. Oct. 16, 2015), ECF No. 642; Verdict Form, Power Integrations, Inc. v. Fairchild Semiconductor Int'l, Inc., Case No. 09-cv-05235-MMC (N.D. Cal. Dec. 17, 2015), ECF No. 918; Verdict Form, Wi-LAN, Inc. v. Apple Inc., Case No. 14cv2235 DMS (BLM) (S.D. Cal. Jan 24, 2020), ECF No. 845.

6 The main damages statute in United States patent law states that "the court shall award the claimant damages adequate to compensate for the infringement, but in no event less than a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer, together with interest and costs as fixed by the court." 35 U.S.C. § 284 (2018) (emphasis added). A royalty is "reasonable" when "a person, desiring to manufacture, use, or sell a patented article, as a business proposition, would be willing to pay [that amount] as a royalty" and still make "a reasonable profit." Applied Med. Research Corp. v. U.S. Surgical Corp., 435 F.3d 1356, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (quoting TransWorld Mfg. Corp. v. Al Nyman & Sons, Inc., 750 F.2d 1552, 1568 (Fed. Cir. 1984)). Alternatively, a patentee can seek lost profits when it can demonstrate it would have made sales but for the defendant's conduct. Lost profits claims also require apportionment, though lost profits are less common than reasonable royalties. See Mentor Graphics Corp. v. EVE-USA, Inc., 851 F.3d 1275, 1287 (Fed. Cir. 2017) ("[A]pportionment is an important component of damages law generally, and we believe it is necessary in both reasonable royalty and lost profits analysis.").

7 Garretson v. Clark, 111 U.S. 120, 121 (1884); see also Seymour v. McCormick, 57 U.S. (16 How.) 480, 490-91 (1853) ("[I]t is a very grave error to instruct a jury 'that as to the measure of damages the same rule is to govern, whether the patent covers an entire machine or an improvement on a machine.' ").

8 See, e.g., Lucent Techs., Inc. v. Gateway, Inc., 580 F.3d 1301, 1336-38 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (discussing the origins of the entire market value rule).

9 See Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538, 1549 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (en banc) ("We have held that the entire market value rule permits recovery of damages based on the value of a patentee's entire apparatus containing several features when the patent-related feature is the 'basis for customer demand.'" (quoting

10 State Indus., Inc. v. Mor-Flo Indus., Inc., 883 F.2d 1573, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1989))); see also Lucent, 580 F.3d at 1337 ("The first flaw with any application of the entire market value rule in the present case is the lack of evidence demonstrating the patented method of the [asserted] patent as the basis-or even a substantial basis-of the consumer demand for [the accused product].").

11 See Power Integrations, Inc. v. Fairchild Semiconductor Int'l, Inc., 904 F.3d 965, 979 (Fed. Cir. 2018) ("[W]hen the product contains multiple valuable features, it is not enough to merely show that the patented feature is viewed as essential, that a product would not be commercially viable without the patented feature, or that consumers would not purchase the product without the patented feature. When the product contains other valuable features, the patentee must prove that those other features do not cause consumers to purchase the product."); LaserDynamics, Inc. v. Quanta Computer, Inc., 694 F.3d 51, 68-69 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ("It is not enough to merely show that the [patented feature] is viewed as valuable, important, or even essential to the use of the [entire product]. Nor is it enough to show that [the entire product] without [the patented feature] would be commercially unviable. Were this sufficient, a plethora of features . . . could be deemed to drive demand for the entire product.").

12 Cornell Univ. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 609 F. Supp. 2d 279, 287-88 (N.D.N.Y. 2009).

LaserDynamics, 694 F.3d at 67-68 (citations

omitted) (quoting Cornell, 609 F. Supp. 2d at 28788); see

also Power Integrations, 904 F.3d at 977 ("We have articulated

that, where multi-component products are accused of infringement,

the royalty base should not be larger than the smallest salable

unit

8 IP Litigator MARCH/APRIL 2021 embodying the patented

invention."); VirnetX, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., 767 F.3d

1308, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2014) ("[W]hen claims are drawn to an

individual component of a multi-component product, it is the

exception, not the rule, that damages may be based upon the value

of the multicomponent product.").

To view in full click here

Originally published by IP Litigator

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.