- within Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring and Strategy topic(s)

Achieving the nation's climate targets will require access to raw materials and components along the clean energy and technology supply chains at competitive costs. Currently in the US, these supply chains rely heavily on imports, particularly from China, an imbalance which the US has been working to address through massive incentive programs designed to bolster clean energy and technology development while boosting domestic manufacturing capabilities and the purchase of domestically produced goods. These programs are increasing consumer demand for clean energy and clean technologies such as electric vehicles, as well as key business-to-business demand in areas such as energy storage systems.

While emerging domestic suppliers benefit from favorable trade policy, other companies will need to import raw materials and components to keep up with the pace of demand, at least in the near term while domestic production comes online. Hence, knowing how to navigate trade policy has become an essential part of doing business related to clean energy and technology. This is true whether a company's goal is to strengthen trade restrictions to maintain a competitive domestic advantage or avoid trade restrictions to access or supply raw materials and components needed to meet consumer demand.

Below, we discuss the primary trade restrictions at play and how potentially affected companies can navigate trade policy to hew with their particular situations. Specifically, we review the tools available to companies that may wish to initiate, adjust, continue, suspend, or seek exclusions from trade restrictions. We conclude with next steps.

1. Primary Trade Restrictions Relevant to Clean Energy and Technology Sectors

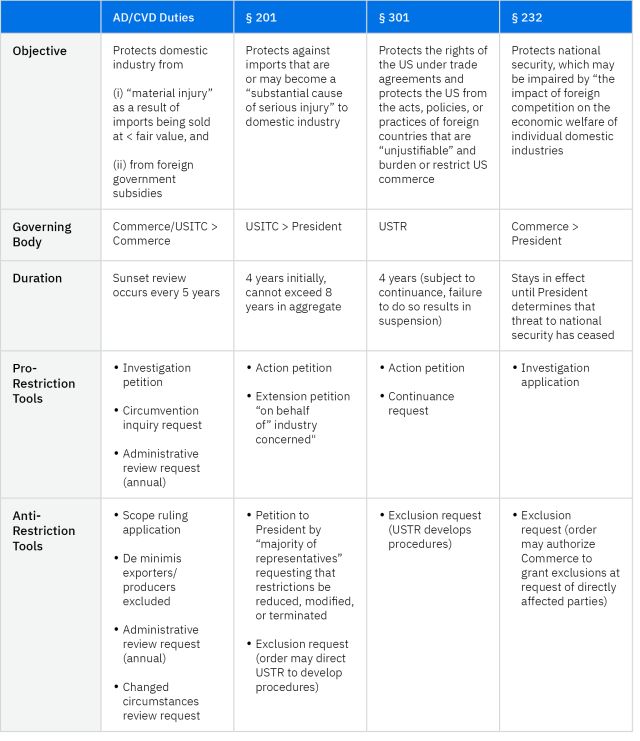

US trade policy will influence the effectiveness of the new incentive programs established to bolster clean energy and technology development. Therefore, it is essential to know how trade restrictions work. The four main categories of trade restrictions are (1) antidumping/countervailing ("AD/CVD") duties, (2) Section 201 restrictions, (3) Section 301 restrictions, and (4) Section 232 restrictions. 1

The general objective of trade policy is to influence the import of goods into the US via the different categories of trade restrictions meant to facilitate specific outcomes. For example, AD/CVD duties seek to offset the "material injury" to domestic industry that results from the dumping of goods into the US at less than their fair value and/or the foreign subsidization of goods imported into the US.2 Similarly, Section 201 restrictions seek to protect US companies from imports that are or may become a "substantial cause of serious injury" to domestic industry.3 By comparison, Section 301 restrictions seek to protect US rights under trade agreements and/or counteract "unjustifiable" foreign activities that burden or restrict US commerce.4 Section 232 restrictions seek to protect national security.5 These goals may be accomplished through the imposition of duties, tariff-rate quotas,6 or other import restrictions.

Companies can seek to influence trade restrictions in several ways, such as by influencing whether restrictions are initiated, adjusted, or continued, by seeking and participating in the process by which companies are granted exclusions, and by influencing the suspension of restrictions.

Table 1 organizes these trade restrictions by objective, governing body, duration, and tools that can be utilized to strengthen the restriction ("Pro-Restriction Tools") or limit the restriction ("Anti-Restriction Tools").

TABLE 1.

Primary Elements of Key Trade Restrictions Affecting Products that Advance Climate Goals

2. Initiation, Adjustment, Continuance, and Suspension

Each trade restriction has its own initiation process. For instance, AD/CVD duties are established through a process led cooperatively by the US Department of Commerce ("Commerce" or "Commerce Department") and the US International Trade Commission ("USITC").7 By comparison, Section 201 and 232 restrictions are established by the President after preliminary determinations are made by the USITC and Commerce Department, respectively.8 The US Trade Representative ("USTR") is responsible for establishing Section 301 restrictions.9

While the federal government ultimately institutes trade restrictions, the restrictions can be initiated by "interested parties" through the filing of petitions or applications. Other interested parties typically can participate in the initiation process, as well. Interested parties generally must be associated with the targeted industry, such as through the manufacture, production, or sale of the targeted product or by being an industry representative.10

With respect to AD/CVD duties, if an interested party believes that companies are circumventing an AD/CVD order, the interested party can seek to subject the companies to the order by submitting a request for a circumvention inquiry to the Commerce Department.11 Such a submission could result in the applicable duties being imposed on the circumventing companies should an affirmative determination of circumvention be made. Interested parties other than the requester can participate in this process by submitting factual information and written argument.

A recent example of circumvention occurred on December 8, 2022, when Commerce made a preliminary affirmative determination that importers from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam were circumventing an AC/CVD order targeting Chinese imports of crystalline silicon photovoltaic cells ("c-Si solar cells") by using parts and components produced in China to produce the c-Si solar cells and then exporting them to the US.12 Should a final determination of circumvention be made, these imports would be subject to the AD/CVD duties that target imports of c-Si solar cells produced in China.13 Notably, to keep up with consumer demand for solar cells and modules needed to produce solar energy, President Biden used his emergency authority to establish a two-year suspension on the imposition of duties on c-Si solar cells from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam.14 Thus, any duties imposed, should a final determination of circumvention be made, likely would not go into effect until after June 6, 2024, unless the emergency were to terminate before that time (i.e., domestic solar component manufacturing capacity were to become sufficient to meet solar generation needs).

In addition to initiating the process to establish trade restrictions and submitting a request for a circumvention inquiry (applicable to AD/CVD duties), interested parties can seek to influence the adjustment, continuation, or suspension of trade restrictions.

For AD/CVD duties, this can be accomplished by influencing the initiation of different types of reviews of the duties, as well as participating in these reviews through the submittal of factual information and written argument.

For example, during every year following the issuance of an AD/CVD order, an interested party can submit an "administrative review" request to petition the Commerce Department to reassess the amount of duties that should be imposed on specified individual exporters or producers covered by the order.15

Interested parties can also participate in a "sunset review" process of AD/CVD orders, which occurs every five years after the establishment of an order at which time the Commerce Department determines whether the order should be continued or suspended.16 Using the example of c-Si solar cells, the next sunset review for AD/CVD duties targeting solar products assembled in China,17 as well as AD duties targeting c-Si solar cells produced in Taiwan,18 will take place in 2025. Notably, 2025 also marks the year in which the Commerce Department will undertake a sunset review of AD duties targeting utility scale wind towers from Canada, Indonesia, South Korea, and Vietnam.19

Finally, an interested party can submit a "changed circumstances" review request and carries the burden of persuading the Commerce Department that changed circumstances are sufficient to warrant revocation of an AD/CVD order.20 Ultimately, Commerce can suspend AD/CVD duties if it finds that revocation of the order is not likely to lead to the continuation or recurrence of the dumping and/or countervailable subsidy and the resulting material injury.

With respect to Section 201 restrictions, a party can file an extension petition with the USITC "on behalf of the industry concerned," and interested parties and consumers can then participate in a public hearing associated with the resulting extension proceeding.21 Ultimately, the USITC will continue the restrictions if they continue to be necessary to prevent or remedy serious injury to the affected domestic industry, and there is evidence that the domestic industry is making a positive adjustment to the import competition. However, under no circumstances can the restrictions exceed eight years in the aggregate.22 Also, if the restrictions are terminated, interested persons can participate in a hearing held on their effectiveness.23

Using the example of c-Si solar cells again, Section 201 duties on imports of c-Si solar cells, originally put into place by President Trump in January of 2018,24 were extended by President Biden for an additional four years in February of 2022.25 Given the eight-year limit, these duties will last no longer than 2026. Prior to 2026, however, "a majority of the representatives of the domestic industry" can submit a petition to the President requesting that the duties be reduced, modified, or terminated, which the President may grant upon a determination that the domestic industry has made a positive adjustment to the import competition.26 The US Court of International Trade has interpreted this provision as allowing a "majority of the representatives" to be based on production volume and as only permitting trade liberalizing modifications.27

For Section 301 restrictions, "industry representatives" that benefit from the restrictions can file a written request for the continuance of the restrictions beyond their general four-year term (indeed, failure to do so results in their termination).28 The USTR may also modify or terminate the restriction on its own initiative prior to the end of the four-year term, and interested persons can participate in this process.29 The USTR is currently in the process of reviewing Section 301 duties targeting various Chinese imports along the clean energy and technology supply chains.30

Finally, Section 232 restrictions, which target steel and aluminum imports from most countries,31 were implemented in 2018 pursuant to President Trump's determination that steel and aluminum imports threaten to impair national security. These restrictions can be lifted only after the President declares that steel and aluminum imports no longer pose a national security threat.

Importantly for this discussion, in September of 2022, the Commerce Department found that imports of neodymium-iron-boron ("NdFeB") permanent magnets, which are used in electric vehicle motors and offshore wind turbine generators, threaten national security. Commerce nevertheless did not recommend the imposition of Section 232 restrictions given the current "severe lack of domestic production capability."32 This may change as the rare earth magnet domestic supply chain develops production capacity and provided it can supply enough NdFeB to keep up with demand.

3. Exclusions

Companies that may be subject to trade restrictions have the potential to benefit from exclusions that work to prevent the restrictions from reaching their businesses.

While there is not a formal exclusion process for AD/CVD duties, an interested party may submit a "scope ruling application" to request that the Commerce Department conduct a scope inquiry to determine whether a particular product is covered by the scope of an AD/CVD order, a process by which an interested party can participate.33 Notably, when Commerce makes a final determination to institute AD/CVD duties, it is required to exclude any exporter or producer that has a de minimis impact.34

For Section 201, 301, and 232 restrictions, the exclusion process is case-specific. For instance, following a Section 201 order, the President may direct the USTR to develop procedures for the exclusion of certain products.35 Similarly, for Section 301 restrictions, the USTR develops exclusion procedures tailored to particular products.36

For the Section 301 duties that target various Chinese imports along the clean energy and technology supply chains currently subject to review, the USTR excluded certain products, and some of these exclusions were reinstated and extended through September 30, 2023, to allow USTR to consider and align the exclusions with the results of its review.37 Affected parties should be closely following USTR developments which will reveal whether the duties will remain in effect, and if so, whether the exclusions will continue.

Finally, following a Section 232 order, the Commerce Department is often authorized by the President to grant exclusions at the request of directly affected parties.38

4. Next Steps

In addition to taking advantage of tax credits and other incentives, emerging domestic suppliers may find it in their best interest to advocate for the initiation or continuation of trade restrictions or to seek to prevent companies from receiving exclusions. By contrast, companies that rely on targeted imports or companies that export targeted products to the US may find it in their best interest to counteract these efforts and advocate for the suspension of restrictions. Notably, given the government's significant investments designed to bolster clean energy and technology development, the government is in a position to protect these investments by being even more mindful of applicable trade policy.

Regardless of the objective, companies should ensure that their interests are adequately represented and advocated for in trade restriction proceedings. As a first step, companies along the clean energy and technology supply chains, as well as companies invested in the development of associated projects, should closely evaluate their supply chains and seek to understand how current and future trade developments may impact their business objectives. In certain cases, it may be worth acting in the US Court of International Trade.

*Summer associates Kate Cox and Joseph S. Jazwinski made special contributions to this article.

Footnotes

1. AD/CVD duties are provided by the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended. 19 U.S.C. §§1671-1677n; 19 C.F.R. Part 351. Section 201 and 301 restrictions are provided by the Trade Act of 1974. 19 U.S.C. §§2101-2497b. Section 232 restrictions are provided by the Trade Expansion Act of 1972. 19 U.S.C. §1862; 15 C.F.R. Part 705.

2. 19 U.S.C. §§1673, 1671.

3. Id. §2251(a).

4. Id. §2411(a)(1).

5. Id. §1862(c).

6. Tariff rate quotas permit a specified quantity of imported merchandise to be entered at a reduced rate of duty during the quota period. Once the tariff-rate quota limit is reached, goods may still be entered but at a higher rate of duty.

7. See generally 19 U.S.C. §§1673-1673i (AD), 1671-1671h (CVD); 19 C.F.R. Part 351, Subpart B.

8. 19 U.S.C. §§2251(a) (201), 1862(b) (232).

9. Id. §2411.

10. E.g., id. §§1673a(b) (AD), 1671a(b) (CVD), 1677(9) (defining "interested party").

11. Id. §1677j; 19 C.F.R. §351.226(c).

12. 87 Fed. Reg. 75221 (Dec. 8, 2022).

13. 77 Fed. Reg. 73018 (Dec. 7, 2012) (AD order); 77 Fed. Reg. 73017 (Dec. 7, 2012) (CVD order).

14. The White House, Declaration of Emergency and Authorization for Temporary Extensions of Time and Duty-Free Importation of Solar Cells and Modules from Southeast Asia (June 6, 2022).

15. 19 U.S.C. §1675(a); 19 C.F.R. §351.213.

16. 19 U.S.C. §1675(c); 19 C.F.R. §351.218.

17. 80 Fed. Red. 8592 (Feb. 18, 2015).

18. 80 Fed. Reg. 8596 (Feb. 18, 2015).

19. 85 Fed. Reg. 52546 (Aug. 26, 2020); see also 86 Fed. Reg. 69014 (Dec. 6, 2021); 86 Fed. Reg. 69012 (Dec. 6, 2021).

20. 19 U.S.C. §1675(b); 19 C.F.R. §351.216.

21. 19 U.S.C. §2254(c). Note that the statute does not require a party to be an interested party to file an extension petition.

22. Id. §2253(e)(1).

23. Id. §2254(d).

24. 83 Fed. Reg. 3541 (Jan. 25, 2018).

25. 87 Fed. Reg. 7357 (Feb. 9, 2022).

26. 19 U.S.C. §2254(b)(1)(B).

27. Solar Energy Indus. Ass' v. United States, 553 F. Supp. 3d 1322 (Ct. Int'l Trade 2021).

28. 19 U.S.C. §2417(c).

29. Id. §2417(a)(2).

30. See 83 Fed. Reg. 28710 (June 20, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 40823 (Aug. 16, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 47974 (Sept. 21, 2018), as modified by 83 Fed. Reg. 49153 (Sept. 28, 2018); and 84 Fed. Reg. 43304 (Aug. 20, 2019), as modified by 84 Fed. Reg. 69447 (Dec. 18, 2019) and 85 Fed. Reg. 3741 (Jan. 22, 2020).

31. 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (Mar. 15, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 11619 (Mar. 15, 2018).

32. 88 Fed. Reg. 9430 (Feb. 14, 2023).

33. 19 C.F.R. §351.225(c), (f).

34. Id. §351.204(e)(1).

35. See, e.g., 83 Fed. Reg. 6670 (Feb. 14, 2018).

36. See, e.g., 84 Fed. Reg. 29576 (June 24, 2019).

37. 87 Fed. Reg. 78187 (Dec. 21, 2022).

38. See, e.g., 15 C.F.R. App. Suppl. No. 1 to Part 705.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.