A. RECENT TRENDS AND PATTERNS IN FCPA ENFORCEMENT

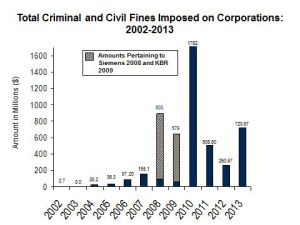

Last year, we noted that 2012 had been "a fairly slow time" in terms of corporate enforcement actions, with twelve enforcement actions against corporations. 2013 was slower still, with only nine corporate enforcement actions. There was a steep increase in corporate fines, however, and enforcement against individuals saw a marked increase, from five in 2012 to sixteen in 2013—eight of whom pleaded guilty.

Among the highlights:

- Over $720 million in penalties in 2013, and the average penalties ($80 million) and the adjusted average ($28 million) were both considerably up from previous years;

- Significant number of new cases against individuals;

- Surge in "hybrid" monitors, with an independent monitor's term of 18 months followed by 18 months of self monitoring;

- Continued aggressive theories of jurisdiction and parent subsidiary liability; and

- Adoption of deferred prosecution agreements in the U.K., albeit with substantially more judicial involvement than in the U.S.

Enforcement Actions and Strategies

Statistics

In 2013, the government brought nine enforcement actions against corporations: Philips, Parker Drilling, Ralph Lauren, Total, Diebold, Stryker, Weatherford, Bilfinger, and Archer Daniels Midland (ADM).

This is the lowest number in the past seven years, which had seen annual totals averaging thirteen cases per year since 2007. Most of these cases were coordinated actions brought by both the SEC and the DOJ, with only two independent actions brought by the SEC (Philips and Stryker) and one from the DOJ (Bilfinger). It is difficult to say whether the lower rate of corporate enforcement is a trend, in spite of the relatively low twelve corporate enforcement actions in the prior year: although a substantial number of companies have announced new investigations or reserves for enforcement fines in recent years, there have only been a handful of publicly announced declinations. The regulators, for their part, have swept aside any suggestions of waning enforcement, stating that both the DOJ and the SEC have a substantial pipeline of FCPA cases awaiting announcement.

In contrast with the lower number of corporate matters, the year saw a surge in individual actions, with twelve charged in 2013. In addition, four individual actions brought in 2012 were unsealed in 2013 (thus we have included them in our statistics for 2013). Only five of these individual actions were connected with previous enforcement actions: Jald Jensen, Bernd Kowalewski, Neal Uhl, and Peter Dubois (incidentally, the group of individuals whose filings were belated unsealed in 2013) were all affiliated with Bizjet, which settled with the DOJ in 2012; and Alain Riedo was a Swiss national executive at Maxwell Technologies, which settled with the DOJ and SEC in 2012. The remaining eleven fell into two group actions, and one rather unique freestanding action: Lawrence Hoskins, Frederic Pierucci, William Pomponi, and David Rothschild were employed by and participated in a scheme at French company Alstom SA (which has not been subject to an enforcement action—yet), while Iuri Rodolfo Bethancourt, Tomas Alberto Bethancourt Clarke, Jose Alejandro Hurtado, Haydee Leticia Pabon, Maria de los Angeles de Hernandez Gonzalez, and Ernesto Lujan allegedly participated in a scheme involving a New York broker dealer called Direct Access Partners, LLC. Among the broker dealer defendants, Gonzalez was a Venezuelan government official charged not with FCPA bribery but with money laundering and Travel Act violations for accepting bribes. The final individual action was an obstruction of justice case against Frederic Cilins, a French national who allegedly interfered in a government investigation into a mining company's potential violations of the FCPA in Guinea. Press reports indicate that the mining company is Beny Steinmetz Group Resources (BSGR), which has denied any wrongdoing but is under investigation in several countries, including Switzerland.

On the penalties side, the corporate penalties assessed in 2013 were markedly higher than in 2012 and rebounded to levels last seen in 2010. Altogether, the government collected $720,668,902 in financial penalties (fines, DPA/NPA penalties, disgorgement, and prejudgment interest) from corporations in 2013. This equates to an average of $80 million per corporation, with an exceptionally large range of $1.6 million (Ralph Lauren) to $152.79 million (Weatherford) and $398.2 million (Total). Weatherford and Total's penalties are, each respectively, over three times that of any of the other companies. Weatherford's high fines appear to stem from the company's widespread bribery schemes and particularly "anemic" compliance systems and controls, as well as its initial failure to cooperate with the authorities. Total engaged in a bribery scheme that spanned a decade and resulted in over $150 million in profits, resulting in the second highest disgorgement in FCPA enforcement history. Meanwhile, Ralph Lauren's low fines were purportedly the result of the "exceptional" self reporting, cooperation, and remediation that led to an unprecedented double NPA, although the isolated nature of the bribes (and resulting low disgorgement) likely factored in as well. When we remove those three outliers, the average is $28 million. This is in line with the averages calculated in recent years using the same criteria ($17.7 million in 2012, $22.1 million in 2011).

|

|

On the individuals side, Riedo is a fugitive and two others, Cilins and Alstom executive Pomponi, are each pending trial. Two of the Alstom defendants, Rothschild and Pierucci, have pleaded guilty, while the status of the fourth Alstom defendant Hoskins is yet unclear. Similarly among the Bizjet defendants, the status is unclear for two defendants (Jensen and Kowalewski) while two pleaded guilty (Uhl and DuBois). Uhl and Dubois were each sentenced to 60 months' probation and 8 months' home detention, with a $10,100 fine imposed on Uhl and a $159,950 fine imposed on DuBois. Finally, all four of the broker dealer defendants in the DOJ proceedings (Clarke Bethancourt, Hurtado, Gonzalez, and Lujan) have pleaded guilty, with sentencings scheduled for 2014. The parallel civil proceedings (with additional defendants Bethancourt and Pabon) were stayed pending resolution of the criminal case, and the stay had not been lifted as of December 2013.

In addition to the relative profusion of new individual enforcement, there were sentencings and other case developments in numerous pending actions. After a slew of guilty pleas last year, three CCI defendants were sentenced: Flavio Ricotti to time served and Mario Covino and Richard Morlok to three years' probation and three years' home confinement. The CCI cases are thus fully resolved, save for Korean national Han Yong Kim, whose request to make a "special appearance" was denied in June.

Meanwhile, in the case against the Siemens executives, the DOJ's cases appear to be stalled, with none of the defendants choosing to come to the U.S. to answer charges and apparently no success thus far in obtaining extradition of them. On the other hand, the SEC civil enforcement action seems close to being resolved, albeit in some strange and uneven ways. Herbert Steffen's motion to dismiss was granted for lack of jurisdiction and the SEC voluntarily dismissed all claims against Carlos Sergi, while Uriel Sharef settled with the SEC for a $275,000 civil penalty—the second highest penalty assessed against an individual in an FCPA case. The SEC indicated that it has reached an agreement in principle to settle claims against Andres Truppel, and has requested that the court enter default judgments against Stephan Signer and Ulrich Bock.

In contrast, the three Magyar Telekom executives charged by the SEC, Elek Straub, Andras Balogh, and Tamas Morvai, are apparently proceeding to trial and the case has now entered the pretrial discovery phase, after the defendants' motions to dismiss were denied in February 2013. Similarly, the Noble executives James Ruehlen and Mark Jackson are also on their way to trial; after considerable pretrial litigation (discussed below) regarding the statute of limitation and other issues resulting in the SEC filing an amended complaint in March 2013, Ruehlen and Jackson filed answers on April 2013, denying most of the SEC's allegations.

In yet another case with multiple individual defendants, Haiti Telecom, the legal battles continue: briefs were filed in the appeal of Jean Rene Duperval, while oral arguments were held in the appeal of Joel Esquenazi and Carlos Rodriguez. Three of the remaining defendants (Washington Vasconez Cruz, Amadeus Richers, and Cecilia Zurita) have been classified as fugitives, and Marguerite Grandison's case was closed when she entered into an eighteen month diversion program.

Finally, the year also saw resolutions from the rather distant past, with Thomas Farrell, Clayton Lewis, and Hans Bodmer (all charged in 2003) each sentenced to time served, and Paul Novak (charged in 2008) sentenced to fifteen months in prison and a $1 million fine. In addition, Frederic Bourke's (charged in 2005) long legal journey finally came to an end—after two unsuccessful appeals of his original 2009 conviction, the United States Supreme Court refused to hear his case. He began his prison sentence of one year and one day in May 2013.

Types of Settlements

As in the past, nearly all of the criminal corporate resolutions were in the form of deferred or non prosecution agreements, with only one corporation pleading guilty to an offense (ADM's subsidiary, Alfred C. Toepfer International (Ukraine) Ltd.). The civil corporate resolutions took the form of administrative cease and desist orders and civil settlements, with one notable exception—the SEC's first-ever FCPA-related non-prosecution agreement with a company (Ralph Lauren). As we noted last year, however, the government has not been clear as to the factors that influence the type of settlement, and unfortunately, the Ralph Lauren double NPA does not supply any meaningful clarity. Both the SEC and DOJ credited Ralph Lauren's prompt self reporting, remedial measures, and "extensive, thorough, real time cooperation," including measures such as revising and enhancing compliance policies and conducting a world wide risk assessment. The SEC also noted that Ralph Lauren ceased retail operations in Argentina, the site of the alleged bribes. Yet, it is difficult to distinguish these factors from those set out by the SEC (albeit in a less effusive manner) in Philips, a case that predated Ralph Lauren: self reporting, cooperation, and "significant remedial measures" but Philips was subject to an administrative cease and desist order. Moreover, as we have noted before, although we, too, would like to get NPAs rather than DPAs for our clients, the practical consequences are still the same—allegations of wrongdoing (with admissions in DOJ cases), penalties, monitoring or reporting, tolling of the statute of limitations, limits on public statements, and bad publicity.

Interestingly, subsequent to the Ralph Lauren NPAs, nearly every enforcement action contained allegations of at least one notable deficiency in the self reporting/cooperation/remediation process: Diebold only undertook "some" remedial measures that were "not sufficient to address and reduce the risk of occurrence" (which led to the decision to impose a monitor); Stryker, Weatherford, and Bilfinger did not self report; Weatherford engaged in misconduct during the SEC's investigation; and Bilfinger's cooperation came "at a late date." The ADM settlement documents did not contain overt references to any shortcomings in the self reporting company's cooperation or remediation, but while the parent company was granted an NPA, it still had to settle civil charges by the SEC and its subsidiary pleaded guilty to criminal charges.

Elements of Settlements

Monitors. Independent compliance monitors made a comeback in 2013, albeit in the hybrid form we have seen in recent years, in which the monitor's term is only eighteen months followed by eighteen months of self reporting. Out of seven DOJ actions, monitors were imposed on four companies: hybrid monitors for Diebold, Weatherford, and Bilfinger, and a full three-year monitor for Total. Consistent with the DOJ's approach in other recent cases against foreign companies, the DPA specifies that the monitor is to be a French national. Parker Drilling, Ralph Lauren, and ADM agreed to self report for the duration of their respective settlement agreements.

We have previously noted the lack of clarity in what factors lead to an independent compliance monitor. The year's enforcement actions, however, showed a measure of transparency in the government's reasoning, which seemed to place weight on the company's ability to remediate its past wrongdoing. For example, in the DPA with Diebold, the DOJ stated that Diebold's remediation was "not sufficient to address and reduce the risk of recurrence of the Company's misconduct and warrants the retention of an independent corporate monitor." In contrast, the DPA with Parker Drilling (which was allowed to self monitor) gave a long list of examples of the company's "extensive" remediation. As to the other actions, it seems reasonable that Ralph Lauren would not have a monitor, given the double NPA and the smaller scope of the alleged scheme. It seems equally reasonable for Total to have a monitor, given the severity of its offense and the total lack of any references to remediation in its DPA. In contrast, Weatherford's DPA gives a long list of the "extensive" remediation the company undertook, but it also mentions the "extent and pervasiveness of the Company's criminal conduct," which may have tipped the balance toward a monitorship. The Bilfinger DPA gives only a general and brief description of cooperation and remediation, but it does note that Bilfinger's cooperation came "at a late date."

Discount. In prior years, companies have typically received discounts from the Sentencing Guidelines as a reward for their cooperation and settlement. Where no discounts were granted, the fines would generally be at the very bottom of the range set by the Sentencing Guidelines. In 2013, however, both Total and Bilfinger received fines that were higher than the bottom of the Sentencing Guidelines range, Weatherford's fine was squarely at the bottom of the range, and only three companies received discounts: Diebold (30%), ADM Ukraine (30%), and Parker Drilling (20%). ADM Ukraine received an additional deduction of $1,338,387 to account for a fine imposed by German authorities on ADM Ukraine's direct parent company, Alfred C. Toepfer International GmbH. Such unusual circumstances aside, the factors that affected the imposition of monitors—remediation, cooperation, and severity of the offense—seem to also affected the discount. Foreign corporations appear to be getting the short end of the stick (Diebold, Parker Drilling, ADM, and Ralph Lauren are all U.S. companies), but this is likely because non-U.S. companies may not be as willing to cooperate with U.S. government authorities nor, perhaps, have the requisite savvy to navigate the process of cooperating with an overseas regulator.

Approval of Settlements. SEC civil settlements against companies for FCPA violations tend to be approved within thirty days, but, as we noted last year, U.S. District Judge Richard Leon refused to "rubber stamp" two pending settlements: Tyco (settlement agreement signed in 2012) and IBM (settlement agreement signed in 2011). In doing so, he stated that he was "increasingly concerned" by the SEC's settlement policies, and he refused to approve the deal with IBM unless the company agreed to file reports to the court about its compliance program and any potential FCPA violations. IBM, backed by the SEC, had argued that such reporting would be too burdensome, but the company ultimately agreed to modified reporting and Judge Leon approved the settlement in July 2013. Under the new terms of the settlement, IBM is required to: 1) file annual reports to the court and SEC describing its anticorruption compliance programs; 2) immediately report any reasonable likelihood of FCPA violations; and 3) report within 60 days of learning that it is subject to any criminal or civil probe or enforcement proceeding. Tyco's settlement, which had already included reporting requirements, received approval in June 2013.

Judge Leon's intervention, though unusual, was not particularly controversial given that court approval is part and parcel of a civil settlement. DPAs, on the other hand, have been viewed as being exempt from judicial scrutiny—until July 2013, when Judge John Gleeson of the Eastern District of New York published a lengthy written opinion in U.S. v. HSBC Bank USA holding that a court has authority to approve and oversee the implementation of a DPA pursuant to its "supervisory power."

Judge Gleeson, acknowledging that his was a "novel" theory, noted the importance of the supervisory power in "preserv[ing] the judicial process from contamination," and reasoned that, since the parties "have chosen to implicate the Court in their resolution of this matter," the court would not be a "potted plant." Nonetheless, Judge Gleeson recognized the "significant deference" the court owed to the government and approved the DPA "without hesitation." However, in a similar vein to Judge Leon's reporting requirements, he ordered the government and HSBC to file quarterly reports keeping the court apprised of all significant developments in the implementation of the DPA. Judge Gleeson also clearly distinguished DPAs from NPAs, noting that the latter is "not the business of the courts" as it falls within the government's "absolute discretion to decide not to prosecute."

While not an FCPA case, the HSBC USA case does raise the question of whether courts will exercise such authority in overseeing and approving DPAs in future FCPA enforcement actions. Given Judge Gleeson's own discussion of DPAs vs. NPAs—and the functional equivalent of the two in terms of admissions, penalties, and supervision—the risk that a court may examine the merits (and factual predicates) of a proposed DPA may well cause the DOJ to be more willing to proceed on the NPA path in the future.

To read this Report in full, please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.