- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Healthcare and Law Firm industries

- in United States

- within Law Department Performance, Accounting and Audit and Law Practice Management topic(s)

Privacy Class Actions

I. Executive Summary

As technology evolves, businesses across the world purposefully have increased their use and reliance on technologies that obtain biometrics and other personal information for various innovative and useful purposes. These technologies enhance the accuracy of their timekeeping systems, facilitate consumer transactions and website advertising, and improve products and services. Both the federal government and a handful of states across the country anticipated this type of evolution and passed laws to protect the security of biometric data and to protect against the potential harm of data theft involving sensitive biometric identifiers.

Class action litigation has inevitably ensued.

Plaintiffs are increasingly invoking federal and state wiretapping statutes, eavesdropping statutes, unfair and deceptive practices statutes, and a wide variety of other legal theories to attack ubiquitous website advertising technologies – called adtech – like Meta Pixel and Google Analytics and other technologies. Although some of these laws were passed decades ago, the past few years have seen a rapid rise of newly filed class action lawsuits attempting to apply them to these and other technologies. As such, the courts have been tasked with interpreting these statutes in novel ways that are rapidly evolving the understandings of privacy laws in the United States.

In 2024, the courts issued a mixed bag of results leading to major victories for both plaintiffs and defendants. For instance, the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) remains the most controversial and hotly litigated privacy law in the country. The BIPA, which was originally enacted in 2008, prohibits companies from collecting individuals' biometric data without the requisite notice and consent. In the last several years, the number of BIPA cases has more than quadrupled as the plaintiffs' class action bar has filed a surge of claims for alleged biometric privacy violations. In 2024, courts issued numerous mixed rulings regarding whether companies' technologies violated the BIPA, including, for example, on the issue of whether plaintiffs plausibly alleged that facial analysis technologies performing functions other than facial recognition obtained facial data "biologically unique to the individual." See 740 ILCS 14/5(c).

In 2024, courts also issued mixed rulings regarding whether companies' use of adtech violated federal and state wiretap statutes and other data privacy laws.

These rulings have far-reaching implications since statutory damages can reach up to $5,000 per violation for the BIPA and similarly staggering statutory penalties under other privacy laws that similarly do not require a plaintiff to show any actual damages under other data privacy statutes. So long as courts continue to issue mixed rulings under BIPA for companies' uses of non-facial recognition technologies, for their uses of adtech, and for alleged improper collection of genetic information, high-stakes cases involving these technologies and processes will continue to proliferate.

Against this backdrop, corporate decision-makers can expect to continue to see several key trends in 2025.

First, in terms of numbers, privacy class actions have outpaced filings in other areas of law in terms of growth, likely due to the relative newness of this area of law, lack of clarity on how to interpret these statutes, and stiff statutory penalties for violations.

Second, the landscape of privacy litigation remains very much in flux. In these class actions to date, the plaintiffs' bar primarily has alleged that defendants improperly collected biometric and other types of personal data. In response to these lawsuits, defendants have mounted a litany of defenses, many of which remain untested or unsettled. While this has been the trend for nearly half a decade, litigants are still working through a patch-work quilt of rulings that are still in desperate need of clarity and consistency.

Third, these factors have contributed to a wave of high-dollar-value settlements in 2024. One involving the State of Texas suing Meta Platforms for privacy violations settled at $1.4 billion. In addition, over the past three years, defendants have agreed to several eight-figure settlements stemming from privacy class actions against some of the most influential and sophisticated companies in the world, including Google, TikTok, Oracle, and Meta.

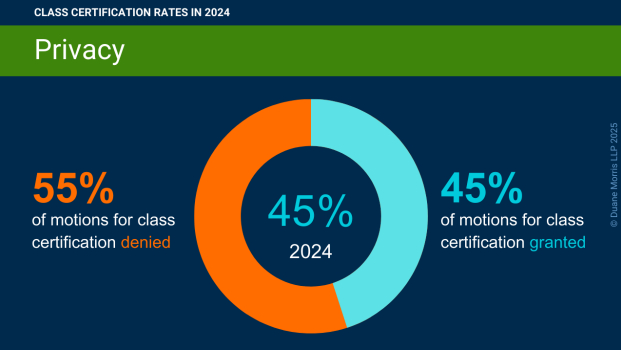

Reflective of this trend are class certification success rates. In 2024, the plaintiffs' bar succeeded in certifying 45% of their motions for class certification in privacy cases.

II. Key Rulings In Privacy Class Actions

1. Rulings On Class Certification Motions In Privacy Class Actions

This past year saw multiple rulings on motions for class certification in the privacy space.

For example, in Howe, et al. v. Speedway, LLC, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 176263 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 29, 2024), a federal court denied the defendant's motion for summary judgment and granted the plaintiffs' motion for class certification. The plaintiff filed a class action alleging that the defendant's use of finger-scanning timeclocks for employees violated the BIPA. The defendant used finger-scan timeclocks for its employees to clock in and out of work "to avoid the problem of 'buddy punching' (clocking in and out for someone else)." Id. at *1. These timeclocks scanned a rectangular, partial portion of an undisputed fingerprint and then created an alphanumeric code. The court denied the defendant's motion for summary judgment and granted the plaintiff's motion for class certification. First, the court rejected the defendant's argument, as "a matter of first impression," that the term "fingerprint" does not include partial prints or partial finger scans. Id. at *7. The court held that the term "fingerprint" means "the ridges of the finger (or a portion of the distinctive pattern of lines on a finger), as long as that portion of the finger's ridges or pattern is sufficient to be unique to a particular individual and is capable of being used to identify a particular person." Id. As a result, the court concluded that the particular partial prints at issue qualified as "biometric identifiers" and by extension that the alphanumeric code was "biometric information under [the] BIPA." Id. at *8. The court rejected the defendant's argument that no reasonable jury could find that it acted negligently or recklessly, including because "there is nothing in the record showing that Speedway took any effort to review the requirements of the BIPA [enacted in 2008] or determine whether it was following the statute at any point before 2017 when it developed and implemented the consent form." Id. at *32-33. The court also rejected the defendant's assumption of risk, waiver, and constitutional defenses, finding them unavailable in defense of a BIPA claim as a matter of law. Finally, the court granted the plaintiff's motion for class certification.

The defendant did not contest numerosity or commonality, and its predominance arguments relied on the viability of affirmative defenses that the court rejected as a matter of law. The defendant also argued that a class action lacked superiority "because damages could reach $14.4 million to $72 million, plus attorneys' fees, and are out of proportion to the harm suffered by the plaintiff and the putative class." Id. at *53-54. The court rejected this argument, stating that "potential due process concerns will be resolved when setting the damages amount (if liability is established), and do not provide grounds to deny class certification at this stage." Id. at *54. Accordingly, with this decision in place, the court ordered the parties to engage in settlement discussions and, if unsuccessful, provide the court an estimate of the trial length.

Griffith, et al. v. TikTok, Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 176403 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2024), was one of the first cases in 2024 to address a motion for class certification in an adtech case on the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), the CIPA, and other claims. The plaintiffs, non-TikTok users, visited several organizations' websites that installed the TikTok Pixel. The plaintiffs filed a class action alleging that TikTok and Bytedance Inc.'s use of software to gather information about non-TikTok users visiting third-party websites violated federal and state privacy laws. Specifically, the plaintiffs brought claims for invasion of privacy, larceny, conversion, and violation of the federal and California wiretap acts (the ECPA and the CIPA). The plaintiffs filed a motion for class certification of several classes, and the court denied the motion. The court concluded that the plaintiffs failed to prove that the Rule 23 requirements of commonality, typicality, and predominance had been met, because the plaintiffs essentially alleged that the defendants violated their privacy and property rights by collecting valuable and sensitive personal information when they visited websites with the Pixel installed. Id. at *13. Thus, the court stated that the viability of the plaintiffs' claims depended on the nature of the information sent to the defendants. Id. The court noted that the information varied widely by website and by class member, based at least on differences in: (i) how each website chose to implement the defendants' software; (ii) the nature of the website; and (iii) the class member's activity on the site. Id. at *13-14. The court reasoned that these extensive variations between class members and websites mattered significantly because they required the plaintiffs to establish on a class-wide basis whether the expectation of privacy was reasonable and whether any intrusion was highly offensive. Id. at *14. As a result, the court ruled that the plaintiffs' claims failed to meet the commonality or typicality requirements for class certification. For these reasons, the court denied the plaintiffs' motion for class certification.

In Duron, et al. v. Loews COH Operating Co. LLC, Case No. 18-CV-6479 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 10, 2024), the court denied the plaintiff's motion for class certification in a class action alleging that the defendant, a software provider, violated the BIPA. The court ruled that the lead plaintiff was an unsuitable class representative, as he was largely uninvolved in the case. During his June 2022 deposition, the plaintiff testified that he did not know which attorneys were handling his case and had only seen the amended complaint days before. The court determined that a lead plaintiff must fulfill a fiduciary duty to monitor the case and be engaged, which the plaintiff failed to do. The court thereby denied the plaintiff's motion for class certification.

In Kellman, et al. v. Spokeo, Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 95525 (N.D. Cal. May 29, 2024), the plaintiffs filed a class action alleging that the defendant violated their statutory rights of publicity and common law rights regarding misappropriation of name and likeness by operating a website that collects consumer and public data from various public sources and private vendors, associates that data with names, and publishes it online. The plaintiffs filed a motion for class certification pursuant to Rule 23, and the court granted the motion. The court determined that the plaintiffs' claims were typical to those of the class because they all involved the publication of teaser profiles without obtaining their consent. The court ruled that the plaintiffs and their counsel were adequate representatives of the class, thereby meeting the requirements of Rule 23(a)(4) because their claims aligned with those of other class members, and the plaintiffs' counsel was experienced in handling similar class actions. The defendant argued that the plaintiffs failed to meet the commonality and predominance requirements as individual issues predominated over common questions. The court rejected the defendant's argument. It found that common issues regarding the defendant's liability for using individuals' identities without consent predominated over any individual claims. Further the court stated that the common question of whether the defendant's actions violated the user's consent was capable of class-wide resolution. The court concluded that a class action would be the superior method of adjudication because of the common questions of law and fact, centralized management in the district where the defendant is located, and the lack of any competing litigation alleging the same claims. For these reasons, the court granted the plaintiffs' motion for class certification.

In Svoboda, et al. v. Amazon, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 58867 (N.D. Ill. Mar. 30, 2024), the plaintiffs filed a class action against Amazon based on a third-party application. Amazon sells products to consumers on its mobile website and shopping application. Its Virtual Try-On or VTO technology allows users to virtually try on makeup and eyewear and is exclusively available on mobile devices. VTOs are software programs that use augmented reality to overlay makeup and eyewear products on an image or video of a face, which allows shoppers to see what the product might look like prior to deciding whether to purchase it. During the relevant class period, there were two VTOs at issue, one of which was developed by a third party (ModiFace), and another which was developed in-house by Amazon that later replaced ModiFace. Id. at *4. Amazon's VTOs come in two forms, including: (i) VTO technology available for lip products; and (ii) VTOs available for glasses. The ModiFace VTO is available for lip liner, eye shadow, eye liner, and hair color. Amazon licenses, rather than owns ModiFace VTO. Id. at *5.

Both Amazon and ModiFace VTOs essentially works the same for every user. To access Amazon's virtual try-on technology, the user first begins by clicking a "try on" button on an Amazon product page (the use of this try-on feature is entirely optional and does not serve as a barrier to the customer actually purchasing the product). Id. The first time the customer uses Amazon VTO, she is shown a pop-up screen that states, "Amazon uses your camera to virtually place products such as sunglasses and lipstick on your face using Augmented Reality. All information remains on your device and is not otherwise stored, processed, or shared by Amazon." Id. at *6. Only after granting permission can the customer use the VTO technology to virtually try on the product. Users may select "live mode" or "photo upload mode" to superimpose the try-on product on an image of their own face. For both modes, the VTOs use software to detect users' facial features and use that facial data to determine where to overlay the virtual products. Id. at *6-7. Based on these facts, the plaintiffs brought a class action lawsuit against Amazon, which alleged that the online retailer violated the BIPA's requirements by collecting, capturing, storing or otherwise obtaining the facial geometry and associated personal identifying information of thousands (if not millions) of Illinois residents who used Amazon's VTO applications from computers and other devices without first providing notice and the required information, obtaining informed written consent, or creating written publicly-available data retention and destruction guidelines. Id. at *7.

The plaintiffs sought to certify a class of all individuals who used a virtual try-on feature on Amazon's mobile website or app while in Illinois on or after September 7, 2016. Significantly, pre-certification discovery established that at least 163,738 people used VTO technology on Amazon's platforms while in Illinois during the class period. Id. at 6. In ruling in favor of the plaintiffs, the court rejected each of Amazon's arguments as to why the plaintiffs failed to satisfy Rule 23's requirements for class certification. Given the size of the purported class, Amazon did not attempt to contest the numerosity requirement. With respect to the adequacy requirement, Amazon argued that the named plaintiffs were inadequate and atypical because they alleged that they used VTO for lipstick, and not eyewear or eye makeup (while the majority of the proposed class was comprised of individuals who used VTO for eyewear). Amazon further argued that the named plaintiffs had a conflicting interest with the class members who used VTO for eyewear, because the BIPA's healthcare exception bars claims arising from the virtual try-on of eyewear. Id. at *12. The court rejected this argument. It found no evidence that the named plaintiffs' interests were antagonistic, or directly conflicted with those members who used VTO to try on eyewear, and Amazon's concern that the plaintiffs lacked an incentive to vigorously contest the healthcare exception defense was merely speculative. Id. The court was also satisfied that the plaintiffs' claims arose from the same course of conduct that gave rise to other class members' claims (such as Amazon's purported collection, capture, possession, and use of facial templates via its VTOs) and thus the typicality requirement was satisfied. Id. at *15. Similarly, the court reasoned that common questions of law or fact predominated over any questions affecting individual members, and a class action was superior to other available methods for fairly and efficiently adjudicating the controversy. Id. at *17. Amazon asserted that there was no reliable way to identify class members who used VTO in Illinois during the class period, and thus, individualized inquiries predominated rendering the case unmanageable. Id. at 21. The court rejected this argument. It agreed with the plaintiffs that Illinois billing addresses, IP addresses from which VTO was used, and geo-location data all served as a way of identifying class members. Amazon raised other arguments about the difficulty of identifying potential class members, but the court rejected each of these arguments, observing that the plaintiffs did not need to identify every member of the class at the certification stage. Id. at *23. For these reasons, the court granted the plaintiffs' motion for class certification.

In Bliss, et al. v. CoreCivic, Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7409 (D. Nev. Jan. 16, 2024), the plaintiff filed a class action alleging that the defendant unlawfully recorded privileged calls between herself and her incarcerated clients in violation of the Federal and Nevada Wiretap Acts. The plaintiff filed a motion for class certification, seeking to certify a nationwide damages class of attorneys who received recorded calls from inmates at 20 different locations and a statewide sub-class of attorneys who received such calls from clients at the defendant's facility in Pahrump, Nevada. The court denied the motion. The court opined that determining consent for the recording of calls would require extensive individualized inquiries due to variances in the disclosure of recording practices across different facilities and differences in how attorneys and detainees were informed about these practices. The court stated that assessing whether the recorded calls contained confidential attorney-client communications would also require extensive individualized inquiries, as not all calls may have been privileged. The court reasoned that even if class membership could be established, determining damages would necessitate a detailed review of each recorded call to assess the severity of the violation, the extent of the privacy intrusion, and any actual damages suffered by each attorney, which would vary significantly among class members. For these reasons, the court concluded that individualized consent and damages inquiries would predominate over common questions, making class certification inappropriate. For these reasons, the court denied the plaintiff's motion for class certification.

The court granted the plaintiffs' motion for class certification in Torres, et al. v. Prudential Financial, Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 215487 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 26, 2024). The plaintiffs filed a class action against the defendants Prudential Financial, Inc., ActiveProspect, Inc., and Assurance IQ, LLC alleging that ActiveProspect intercepted and recorded their real-time interactions with a form on Prudential's website without their consent, in violation of the CIPA. The plaintiffs further alleged that Prudential and Assurance aided in this violation. The plaintiffs filed a motion for class certification pursuant to Rule 23, and the court granted the motion. The plaintiffs sought to certify a class consisting of those who visited the Prudential website, filled out the form for a life insurance quote, and had a TrustedForm Certificate URL generated during the specified period. The court first addressed standing and determined that the plaintiffs had standing to bring the case because the interception of communications without consent under the CIPA constituted a substantive legal harm, and not merely a procedural violation. Next, the court found that the common issues - such as whether ActiveProspect's actions were willful, whether the information collected constituted "content" under the CIPA, and whether the interception occurred while communications were "in transit" in California - outweighed any individual questions. Id. at *10-11. The court also noted that the potential damages for each violation under the CIPA could be determined on a class-wide basis. The defendants argued that individualized questions about whether each class member consented to the data collection would predominate. However, the court stated that implied consent could not be assumed merely by a user's prior acceptance of the privacy policy, particularly when they were not notified of ActiveProspect's involvement in data collection. The defendants also contended that Prudential's privacy policy, which was accessible via a link on every page of their website, provided notice of the data collection practice. However, the court agreed with the plaintiffs that the policy did not adequately inform users that their data was being intercepted in real time by a third party, such as ActiveProspect. The court ultimately ruled that the issue of whether Prudential's privacy policy effectively notified users of this practice was a common question that can be resolved at trial. The court further determined that the records in Assurance's database could be used to identify which individuals submitted the forms and had their communications intercepted. Accordingly, the court ruled that class certification was appropriate, and granted the plaintiffs' motion for class certification.

Martinez, et al. v. D2C, LLC, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 178570 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 1, 2024), was another win for adtech defendants in defeating a class certification motion. The plaintiffs sued D2C, LLC d/b/a Univision NOW (Univision), an online video-streaming service. The parties did not dispute, at least for the purposes of class certification, that: (i) Univision installed the Meta Pixel on its video-streaming website; (ii) Univision was a "video tape service provider" and the plaintiffs and other Univision subscribers were "consumers" under the VPPA, thereby giving rise to liability under that statute if the plaintiffs could show Univision transmitted their personally identifiable information (PII) such as their Facebook IDs along with the videos they accessed to Meta without their consent; (iii) none of the plaintiffs consented; and (iv) 35,845 subscribers viewed at least one video on Univision's website. Id. at *2. The plaintiffs moved for class certification under Rule 23. The plaintiffs maintained that that at least 17,000 subscribers, including (or in addition to) themselves, had their PII disclosed to Meta by Univision. Id. at *3. The plaintiffs reached this number upon acknowledging "at least two impediments to a subscriber's viewing information's being transmitted to Meta: (i) not having a Facebook account; and (ii) using a browser that, by default, blocks the Pixel." Id. at *6-7. Thus, the plaintiffs pointed to "statistics regarding the percentage of people in the United States who have Facebook accounts (68%) and the testimony of their expert ... regarding the percentage of the population who use a web browser that would not block the Pixel transmission (70%), to conclude, using 'basic math,' that the class would be comprised of 'at least approximately 17,000 individuals.'" Id. at *17. In contrast, Univision maintained that the plaintiffs failed to carry their burden of showing that even a single subscriber had their PII disclosed, including the three named plaintiffs. Id. at *3.

The court agreed with Univision and held that the plaintiffs did not carry their burden of showing numerosity. First, the court held that the plaintiffs' reliance on statistics regarding the percentage of people who have Facebook accounts was unhelpful, because "being logged in to Facebook" – not just having an account –"is a prerequisite to the Pixel disclosing information." Id. at *18. Moreover, "being simultaneously logged in to Facebook is still not enough to necessarily prompt a Pixel transmission, since a subscriber must also have accessed the prerecorded video on Univision's website through the same web browser and device through which the subscriber (and not another user) was logged in to Facebook." Id. Second, the court held that the plaintiffs' reliance on their position that 70% of people use Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge, which allow Pixel transmission "under default configurations," failed to account for all of the following "actions a user can take that would also block any Pixel transmission to Meta such as enabling a browser's third-party cookie blockers; setting a browser's cache to 'self-destruct'; clearing cookies upon the end of a browser session; and deploying add-on software that blocks third-party cookies." Id. In short, the court reasoned that the plaintiffs did not establish "the means to make a supported factual finding, that the class to be certified meets the numerosity requirement." Id. at *9. Moreover, the court found that the plaintiffs had not demonstrated that "any" PII had been disclosed, including their own. Id. (emphasis in original). Finding the plaintiffs' failure to satisfy the numerosity requirement dispositive, the court declined to evaluate the other Rule 23 factors. Id. at *5.

The Martinez decision can be cited as useful precedent for showing that the numerosity requirement is not met where plaintiffs put forth only speculative evidence as to whether the adtech disclosed plaintiffs' PII and putative class members' PII to third parties. The court's reasoning in Martinez applies not only in VPPA cases but also other adtech cases alleging claims for invasion of privacy, under state and federal wiretap acts, and more. All these legal theories have adtech's transmission of the PII to third parties as a necessary element. In sum, to establish numerosity, plaintiffs must demonstrate, at a minimum, that class members were logged in to their own adtech accounts at the time they visited the defendants' website, using the same device and browser for the adtech and the visit, using a browser that did not block the transmission by default, and not deploying any number of browser settings and add-on software that would have blocked the transmission.

To view the full article click here

Disclaimer: This Alert has been prepared and published for informational purposes only and is not offered, nor should be construed, as legal advice. For more information, please see the firm's full disclaimer.