- within Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

According to numerous media reports, President Donald Trump is strongly considering issuing an executive order directing federal agencies to resume the process rescheduling of cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), a topic we have covered extensively here (the DEA's Rule to Reschedule Cannabis to Schedule III: Process and Timeline); here (ALJ's Hearing on Rescheduling Faces Delay Over Witness Standing); here (Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Rescheduling and the UN Single Convention on Narcotics); and here (ALJ Sets Schedule and Ground Rules for Evidentiary Hearings on Marijuana Rescheduling). Let's start with the obvious: this is GREAT NEWS.

While this comes as a welcome announcement for the cannabis industry, we do not believe that an executive order from the President can reschedule cannabis on its own – further action likely is required by federal agencies.

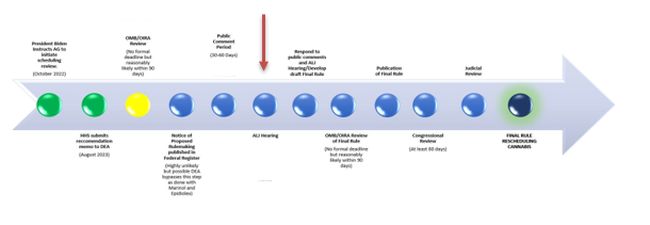

One possibility is that any forthcoming executive order would request the Attorney General to finish the process that began with the formal administrative rulemaking process that began with the Biden Administration's Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NOPR) in May of 2024. The NOPR, as required by the CSA, was published in response to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS) recommendation to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) that cannabis be moved from a Schedule I Controlled Substance to a Schedule III Controlled Substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act. The CSA defines Schedule I controlled substances as having "no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse," but the HHS recommendation concluded that numerous studies dating back to at least 2015 empirically demonstrate cannabis' currently accepted medical use for several indications.

Following the NOPR, the DEA received more than 40,000 public comments and selected interested parties to participate in an adjudicatory hearing before a DEA Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) (a process criticized as one-sided by proponents of the rule and this blog). The process has since stalled following interlocutory administrative appeals from advocates denied status as "interested parties," the DEA's failure to advance the hearing process, and the change in presidential administrations and DEA leadership.

Though much is still unknown, based on media reports, and in line with our reading of the process for reclassification of a Schedule I controlled substance, one option ahead is that the President's executive order would direct the DEA to conclude the hearing process and publish a Final Rule in the Federal Register to reschedule cannabis. This is a process that would require a hearing date, testimony, preparation of the administrative record, and publication of the Final Rule – in other words, a process that could take several months.

We believe it is also possible that the President could order additional studies and/or withdraw the NOPR and essentially start the rulemaking process over again. Needless to say, this route would take the longest to complete Alternatively, it is possible that the President will instruct the Attorney General to utilize a narrow emergency rulemaking procedure authorized by the CSA and the Administrative Procedures Act under the administration's foreign affairs authority (see below). Of course, there is the possibility that nothing happens at all. We certainly have seen the false promise of cannabis reform disappear before our eyes too many times to count.

What is certain is that litigation will result; what is less certain is the timeline for rescheduling and its immediate and long-term impacts. We discuss each below.

What Can the Executive Order Do?

The CSA sets forth a process requiring notice and comment rulemaking, a formal adjudicatory hearing and publication of a final rule, which is then subject to both congressional and judicial review. We wrote about this more here. We are now in the middle of the hearing part of that process.

We should note the CSA permits the Attorney General to bypass the notice and comment period and the hearing process by issuing an "order" to reschedule a drug without engaging in the rulemaking procedures discussed above, in certain limited circumstances, including when the United States is required to "control" a drug pursuant to an international convention, which is the case with respect to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Single Convention). The APA likewise carves out a "foreign affairs function" from these rulemaking requirements, which is applicable in the context of rescheduling cannabis and compliance with the Single Convention. In 2018, the DEA leveraged these authorities to reschedule the FDA-approved drug Epidiolex, a form of purified cannabidiol derived from the cannabis plant used to treat seizures associated with rare forms of epilepsy. We know that the President prefers to order actions and disdains the labor and pace of federal agency rulemaking, but this is a potentially perilous route for the administration as we wrote about here.

OMB Review

Under ordinary circumstances, any final DEA rule would be subject to review by the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) before publication in the Federal Register as a "significant regulatory action" pursuant to Executive Order 12866. The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), part of OMB, will review the proposed rule. Under Executive Order 12866, OMB review of informal rulemaking is subject to a ninety (90) day deadline (extendable for an additional thirty (30) days), whereas formal rulemaking (which is what is now in process) includes no such deadline.

Potential Legal Challenges

An additional legal challenge that could arise is the propriety of an executive order in the rescheduling process. As the CSA directs this process to be scientifically supported – examining the factors under the definitions of Schedule I and Schedule III drugs, such as medical use in treatment and physical and psychological dependence – opponents might argue that rescheduling is not achievable under the plain language of the CSA by presidential discretion, and that the executive order in some way tainted the process.

Otherwise, an appeal of any final rule would likely challenge the administration's scientific findings. Legal arguments might include reference to the CSA's requirement that the Attorney General place drugs "under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out [the United States' treaty] obligations," regardless of the Act's listing criteria or any HHS recommendation. Opponents have argued the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961), to which the US is a signatory, requires a Schedule I or II listing. As we discussed here, we do not agree.

Impacts of Rescheduling

Rescheduling of cannabis to Schedule III would not legalize cannabis. Cannabis will not become legal in states that do not authorize medical and adult use licensed cannabis businesses. But it would have tremendous legal, financial and psychic benefit.

- 280E. The most immediate impact would be that Section 280E of the IRS Code would no longer apply to "plant touching" cannabis companies because the drag of 280E is only applicable to persons "trafficking" in a Schedule I or II controlled substance. While completing the administrative process of rescheduling is slow and painstaking under the CSA, this recommendation supports the arguments of hundreds, if not thousands, of cannabis companies that are taking a position that Section 280E of the IRS Code no longer applies. We discussed this here, where we also note that the IRS does not agree. There are remaining questions whether 280E would apply for any full or partial tax year prior to the effective date of rescheduling, or whether the final rule might plausibly be read to apply retroactively and businesses should consult with their tax and legal professionals on this issue when and if rescheduling occurs.

- Potential Effect on State-Licensed Cannabis Businesses. Unlike Schedule I drugs, there are existing DEA and FDA processes in place for manufacturers and distributors of Schedule III controlled substances (a list that includes steroids and Tylenol with codeine). It is not clear that there will be a quick (or any) effort by the federal government to impose these requirements on state-licensed and regulated cannabis businesses, and even then the rules contemplate that this federally lawful pathway would be available only for medical cannabis companies. At this point, we view the potential for DEA registration as hypothetical. With that caveat, registration requires that registered entities comply with security, recordkeeping, ordering, and reporting controls; transactions must occur among DEA registrants, and dispensing must be for a legitimate medical purpose by DEA‑registered practitioners. By this analysis, state "adult‑use" retail sales would remain unlawful. Businesses that seek to operate within the federal system should plan for DEA controls and FDA compliance (e.g., cGMP for approved drugs, labeling, adverse event reporting), as well as robust documentation, security, and suspicious‑order systems common to controlled substances distribution.

- FDA. FDA could provide certain guidelines or subject cannabis to existing regulatory authority. However, Foley Hoag's FDA specialists caution this is likely to be a slow, incremental process, in the absence of legislation. Some commenters have addressed a fear that FDA regulation will preempt state regulation of cannabis once rescheduling occurs because cannabis will now have accepted medical uses, making it a "drug" within FDA's authority. There are many issues with this line of reasoning. First, FDA has authority today to regulate cannabis and assert jurisdiction. A Schedule I listing is not a bar to FDA enforcement, and one could argue that additional FDA enforcement is inconsistent with the general goals of rescheduling cannabis. Second, some intervening action by FDA or Congress will likely occur before FDA exercises meaningful enforcement oversight with regard to state-legal cannabis. The most likely, as we have seen with hemp-derived cannabidiol (CBD) under the 2018 Farm Bill, could be against state-legal operators that make unproven health claims. Eventually FDA could impose a number of regulatory requirements, such as: labeling restrictions (which could include the requirement of a prescription), identity, purity, and composition standards, establishment registration and product listing, and good manufacturing practices (GMPs) for certain drugs. But there are some important caveats here: FDA regulates drugs in a specific manner, i.e., for specific formulations, specific indications and specific populations. There are countless cannabis formulations and doses being marketed today, and a small body of peer-reviewed research. Regulation of nationwide state-legal cannabis just doesn't fit FDA's drug regulation model. FDA will likely be methodical in asserting its jurisdiction, and if it does, it would probably do so through rulemaking. The more likely scenario (as we've seen with CBD and hemp-derived cannabinoids) is that FDA determines it needs additional authorization and funding from Congress, such as for a cannabis "Center" similar to its "Center for Tobacco Products," before it engages in any comprehensive regulation. Third, FDA preemption is a complex area of law. It is certainly not a foregone conclusion that FDA regulation will completely or even partially preempt state regulation. Preemptive effect – in the absence of new comprehensive cannabis legislation passed by Congress – is likely to be piecemeal. One thing is for sure: there is no FDA playbook for this. It is unchartered territory, and if past is prologue, the agency will be incremental and careful in any assertion of jurisdiction in the absence of new federal legislation.

- Uplisting/Mitigation of Banking/Investment Risk. Rescheduling could cause Nasdaq and NYSE to re-evaluate their position prohibiting the listing of plant-touching U.S. companies. Banking and investment risk may lessen, but not necessarily disappear. Of course, the lesser schedule could change the risk appetite of the capital that remains on the sidelines.

- Interstate Commerce. Rescheduling could result in state laws that require all cannabis sold in state to be produced in state more susceptible to legal challenge under the Dormant Commerce Clause to the U.S. Constitution. There is minimal legal difference in that argument under Schedule I vs. Schedule III, except that more activity is theoretically nationally authorized under Schedule III, such as FDA drug development, scientific research, etc. Those battles would, however, play out piecemeal through the slow churn of litigation. State-by-state, circuit-by-circuit, law-by-law, state laws could fall to commerce clause challenges (as has recently happened to Maine's residency restriction in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit,) until eventually the U.S. Supreme Court does – or does not – issue a ruling. Vulnerable to challenge would be rules that are patently violative of the Commerce Clause (residency restrictions or social equity licensing reservations for residents living in disproportionately impacted areas of a state). The much harder cases would involve rules that require in-state production and sale, along with state-specific testing, labeling, potency, and other standards, which have valid purposes beyond state economic protectionism.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.