- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Healthcare industries

- within Intellectual Property, Cannabis & Hemp and Tax topic(s)

A recent decision of the UK IPO (O/0599/25) has considered key case law relating to patentability of video game mechanics and game rules, and whether there exists a general principle that game mechanics are allowable under s. 1(2) Patents Act 1977 (PA).

Nvidia Corporation sought a patent for a system which used neural networks to generate recommendations (such as in-game hints) for the player of a video game. Refusing the application, the Hearing Officer confirmed that the correct approach with video game mechanics is to consider whether the claimed invention makes a technical contribution to the art. Although the claimed invention was found to be non-obvious, it was determined that the system did not provide a technical effect beyond a computer program and a rule, scheme or method of playing a game as such. As a result, the claimed invention was excluded from patent protection.

Video game patents are a topic of growing interest, and we have recently considered the legal principles in our earlier articles here and here. This latest decision includes helpful discussion of key EPO Board of Appeal cases.

The claimed invention

The invention related to a system for generating recommendations to players of a game. Examples of recommendations included avoiding battles if the player's accuracy or kill rate is low, or to target lower difficulty targets to improve confidence and accuracy.

Player recommendations have been a feature of games for a long time, but a claimed improvement over existing automated systems was an understanding of complex game states. The claimed system could receive data from multiple inputs such as game event data, chat data, biometric data, and player skill data.

The main claim describes use of neural networks to generate recommendations based on identifying relationships between current and previous game states using encoded input data indicating accumulated state changes over time. The processor receives data for multiple input types, transforms the data into feature vectors, encodes these vectors into a latent space, and provides recommendations for presentation to the player.

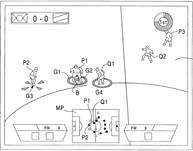

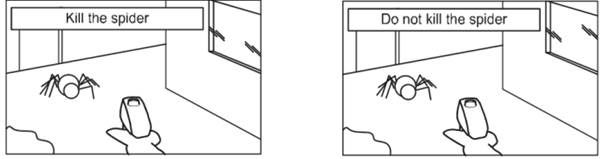

The result, it was claimed, would be that a recommendation for the same in-game event may vary according to contextual data specific to an individual player. This is illustrated by the below images from Figures 3C and 3D of the patent.

Claim 4 of the patent specifies that input types include biological or biometric data and that recommendations include a suggestion that a player takes a break based on that data.

Inventive step

The Hearing Officer applied the usual Windsurfing / Pozzoliapproach to determine whether the patent was inventive. This involves considering whether the differences between the claimed invention and the existing state of the art would have been obvious to the notional person skilled in the art (PSA).

The PSA was found to be a team of video game developers who would be familiar with common game mechanics, conventional computing techniques, and established methods for providing hints or tutorials, such as pop-ups or hint boxes. The Hearing Officer found that team would also be familiar with machine learning and would consult with experts if necessary, given the interdisciplinary nature of modern video game development. This reflects the collaborative approach that is now typical in much of the industry.

Four prior art documents had been cited which disclosed very similar systems involving the use of machine learning to generate tailored recommendations to the player. However, it was found that none of the prior systems disclosed Nvidia's claimed use of a latent space representing accumulated state changes over a time window. Whilst the PSA may have been able to implement the system if they had considered it, there was nothing in the prior art that would have pointed them in this direction. As such, the claims were not obvious.

Patentability of game mechanics

The Hearing Officer applied the usual four-step Aerotel test and the HTC v Apple signposts (which we have previously considered here and here) to determine whether the patent made a technical contribution to the art.

The invention's contribution was its use of a latent space representing data over a time window of gameplay to provide recommendations based on identifying a relationship between a current and previous game state. Nvidia argued that this contribution was technical in nature and did not fall solely within the exclusion in s. 1(2) PA that applies to a scheme, rule or method for playing a game, or a program for a computer, as such.

Nvidia referred to the case law of the EPO Boards of Appeal relevant to video game patents. Nvidia relied on two well-known cases in which video game companies have successfully protected a feature of their video game mechanics: T 0928/03 (Video game/KONAMI); and T 0012/08 (Game machine/NINTENDO).

For ease of reference, the inventions claimed and the outcome in each of these cases is summarised in the table below.

| Case / Patent | Claimed feature | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

|

T 0928/03 (KONAMI) EP0844580 |

Player pass guide mark for use in football-style games. The guide mark identified the player to whom the ball could most easily be passed.

|

It provided a technical solution to a problem caused by conflicting technical requirements: on the one hand, a portion of an image is desired to be displayed on a relatively large scale (zoomed in); on the other hand, the display area of the screen may then be too small to show the complete playable area. The guide mark could identify suitable players outside of the display area, allowing the display area to be zoomed in to show sufficient detail. This was found inventive over other solutions to the problem, such as superimposing a map over the zoomed in display. |

|

T 0012/08 (NINTENDO) EP1078664 |

For use in game where player is moved on a map and encounters game characters. Appearance probability of a character varies in response to time on the physical device.

|

Feature increases unpredictability of the game and holds player attention. Use of the physical device clock to form a random event generator provided a technical solution to a technical problem. This was found inventive over prior art, such as characters in PacMan which blink after a period of time, or the random evasive movement of tanks in Frogger, which did not suggest use of time as a variable in generating random events. |

Nvidia sought to argue that, based on the above cases, the EPO Boards of Appeal distinguish between game rules (which are excluded from protection in light of s. 1(2) PA) and game mechanics (which are not). Whilst clearly the games industry would welcome a general principle that inventive game mechanics are patentable, the Hearing Officer rejected this argument.

It was found that neither KONAMI nor NINTENDO refers to the term "game mechanics". The Hearing Officer determined that both of these cases simply reflect the general principle that a contribution which is technical will be patentable. As summarised in the above table, each of these cases did find the patent to be technical on its facts. As such the key question was not whether the invention was a game mechanic, but whether it made a technical contribution.

A third case, T 0717/05 (Auxiliary game/LABTRONIX), was also cited by Nvidia. This case related to gaming apparatus with an auxiliary game feature that was dependent on past outcomes in the principal game. The invention in that case was found to lay in the system's monitoring and displaying means, which helped to maintain player interest. Nvidia argued that the case establishes that making games more enjoyable or less frustrating is a technical problem. However, the Hearing Officer rejected this in light of a more recent decision in MICROSOFT (T 1281/10), which is favoured by the EPO Guidelines and indicates that amusement and maintaining user interest do not qualify as technical effects.

The Hearing Officer also doubted whether the current invention could be considered a game mechanic in any event. The player recommendations were found to have no effect on the game world, and to be no more a part of the game mechanics than "someone standing over a player's shoulder telling them what to do next".

Turning to the contribution made by the invention, the Hearing Officer followed the Court of Appeal's approach in Emotional Perception (which we have previously considered here and here) and noted that the undoubtedly technical nature of the neural networks used to implement the invention cannot make the invention itself technical unless that system is improved in some way. Here, the recommendations had no clear effect outside the computer and were related to presenting information about the playing of a game. This Hearing Officer agreed with the examiner that the HTC signposts also did not indicate any technical effect.

Although Nvidia had separately argued that claim 4, which provided recommendations based on biometric or biological data should be considered technical, this was also rejected. The invention used conventional means for collecting that data. As such, its contribution was still limited to providing non-technical advice to a player, not solving a technical problem or improving a technical process.

Conclusion

This case is interesting for its discussion and citation of the well-known decisions in KONAMI and NINTENDO, confirming that these remain important examples of how the requisite technical effect may be shown in order to overcome the exclusion from patentability under s. 1(2) PA. This case law shows that the exclusion is not an absolute bar to the patenting of video game mechanics. However, the refusal of Nvidia's system (despite a finding that it was inventive over prior recommendation systems) demonstrates that navigating this exclusion remains a challenge, and that the UK IPO will not accept a broad distinction between "game mechanics" and "game rules" as a shortcut to showing a technical contribution.

As an aside, we would note that there is a pending appeal to the Supreme Court in the key Emotional Technologies case concerning the applicability of the s. 1(2) PA exclusion to artificial neural networks. The hearing in that case commenced on 21 July 2025 (as we discuss here), and the outcome is keenly awaited; if the decision of the Court of Appeal is overturned, this could require a significant change in the approach to examining applications such as the Nvidia patent discussed above. More generally, it is expected that the Supreme Court's judgment will include valuable discussion of the case law relating to computer-implemented inventions.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.