- within Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- with readers working within the Oil & Gas and Law Firm industries

- within Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- with readers working within the Oil & Gas and Law Firm industries

- within Government, Public Sector, Insurance and Tax topic(s)

In line with the present administration's liberalisation policy and the President's directive to the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission ("ICRC") to enhance private sector participation in infrastructure through PublicPrivate Partnerships ("PPPs"), the Federal Government has released new guidelines for the development and implementation of PPP projects.1

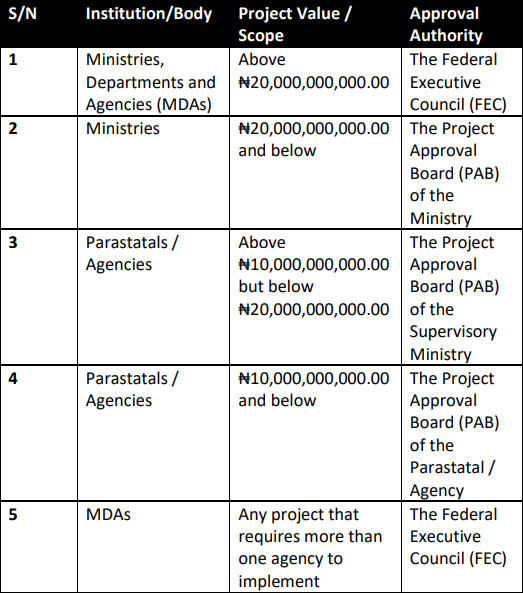

This policy reform represents a significant departure from the previously centralised approval system which required the approval of the Federal Executive Council ("FEC") for all PPP projects. Under the new framework, the granting of approvals for PPP projects has been delegated across tiers of Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs), depending on project size and complexity. Ministries can now approve projects valued at ₦20 billion and below, parastatals and agencies may approve projects ₦10 billion and below, while projects above these two thresholds fall under the purview of the Project Approval Board ("PAB") of the relevant supervisory ministry or, in the case of projects above ₦20 billion or requiring multi-agency implementation, these are to revert to the FEC for approval. For the first time, the guidelines also provide a Project Financial Model Guide, setting out the minimum requirements for building financial models for PPP projects, with the aim of enhancing bankability and consistency in project evaluation.

Together, these measures are designed to streamline the project lifecycle, accelerate investment, deepen private participation, and enhance the efficiency of PPPs as a sustainable infrastructure funding model. Our article reviews Nigeria's PPP framework prior to the 2025 guidelines, with particular attention to the decentralised approval process, the PPP financial model and the role of various project approval boards. It further highlights the key changes introduced in the new guidelines and evaluates their implications for the future of PPP projects in the country.

PPP Framework Prior to the 2025 Guidelines

Nigeria's PPP regime prior to 2025 was premised on the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission Act ("ICRC Act") (2005), and other regulations such as the National Policy on PPP (2009), and the PPP Manual (2018), supported by instruments such as the ICRC concession templates. Together, these provided a solid legal and policy base, with the ICRC overseeing project preparation, compliance, and contract monitoring.

In practice, however, the system was rigid and highly centralised. All projects required Federal Executive Council approval subsequent to ICRC clearance, leaving MDAs with no approval authority. This one-size-fits-all approach created bottlenecks, slowed project delivery, and weakened investor confidence as bankability often depended on sovereign guarantees or direct government support. These inefficiencies underscored the need for the 2025 reforms.

Key Guidelines of the New Framework

Decentralised Approval and Financing Framework

The new guidelines introduce a decentralised approval structure. Ministries can now approve PPP projects valued up to ₦20 billion. The PAB of a supervisory ministry may approve projects above ₦10 billion but below ₦20 billion for parastatals and agencies under their purview, while the PAB of a parastatal or agency may approve projects up to ₦10 billion. Projects exceeding ₦20 billion, or requiring participation by multiple MDAs or subnational governments, remain under the exclusive authority of the FEC. 2

This represents a fundamental shift from the previous framework, where every project, regardless of scale required FEC approval.

Table 1: Approval Thresholds for PPP Projects

On financing, the guidelines stipulate that PPP projects must now be 100% privately financed. Government guarantees, comfort letters, or direct funding are expressly prohibited. This change reduces fiscal risk to the government and places full responsibility for financing PPP projects on the private sector.3

Despite the devolution of approval powers, the ICRC remains central to ensuring compliance and transparency. Every PPP project must secure a Certificate of Compliance from the ICRC as a prerequisite for approval, whether by the FEC or the relevant PAB. Any approval without this certificate will be null and void.4 In addition, the ICRC is mandated to conduct due diligence on prospective PPP partners and verify the compliance of executed agreements.5

Project Approval Board (PAB) Governance Structure and Functions6

The PAB is responsible for approving PPP projects that have obtained a Full Business Case (FBC) Certificate of Compliance duly issued by the ICRC. This certification authorises the execution of the PPP agreement and ensures that the project has met the required technical, financial, and regulatory benchmarks. The PAB thereby serves as the governance mechanism within ministries, parastatals, and agencies, providing oversight before projects are formally executed.

Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Project Financial Model Guide7

A critical addition to the 2025 framework is the PPP Project Financial Model Guide ("the Guide"), which standardises financial models in PPP project preparation, it sets out minimum requirements for financial modelling, ensuring that projects demonstrate bankability, transparency, and value for money before approval can be granted. Previously, financial projections were inconsistent and lacked standardisation. The new guidelines mandate that every project be supported by a comprehensive financial model at both the Outline Business Case ("OBC") and FBC stages. The developed financial model for a PPP project is to reviewed by the ICRC to ascertain the project's financial viability and bankability.

At its core, the Guide requires clear definition of project scope, revenue and cost assumptions, and a balanced financing structure. It places emphasis on sensitivity analysis, revenue shortfalls, inflation, and policy risks while mandating disclosure of mitigation strategies. Key financial metrics key performance indicators such as Net Present Value ("NPV"), Internal Rate of Return ("IRR"), Debt Service Coverage Ratio ("DSCR"), Weighted Average Cost of Capital ("WACC"), and Value for Money ("VfM") tests are now compulsory, aligning Nigerian practice with international PPP standards. The model must detail cost assumptions and projections, financing structure, taxation and accounting assumptions, project cash flows, risk and sensitivity analysis.

Notably, all financial models must be reviewed by the ICRC. This certification validates accuracy, transparency, and compliance with national standards. It also aligns Nigeria's PPP projects with international project finance norms, boosting investor confidence and facilitating access to capital. By embedding financial modelling into the PPP lifecycle, the Federal Government ensures that only financially viable and sustainable projects proceed to approval.

Institutional Mechanisms and Documentation Requirements

The guidelines reinforce the need for clear documentation and institutional processes. MDAs must prepare OBCs and FBCs, submit all agreements for ICRC verification, and adhere to standardised templates for procurement and concession contracts.

Implications for Private Sector Participation and Investment

For the private sector, the reforms open new opportunities but also raise expectations. With financing responsibilities fully shifted to investors, the need for robust due diligence, accurate financial modelling, and transparent risk allocation has never been greater. The standardisation of business cases, coupled with decentralised approvals, is expected to accelerate project timelines and reduce bureaucratic delays.

At the same time, stricter compliance requirements, mandatory ICRC certification, and the absence of government guarantees mean that only well-prepared and financially bankable projects will succeed. This is likely to encourage stronger partnerships between MDAs, investors, and lenders, fostering a more competitive and sustainable PPP market in Nigeria.

Policy Reflections and Outlook

The 2025 Guidelines from ICRC marks a decisive step in Nigeria's efforts to liberalize the PPP environment. By devolving approval authority and introducing a financial modelling standard, the reforms can go a long way in addressing longstanding bottlenecks and bring Nigeria more closely to global best practices. Yet, their success will depend less on the elegance of the rules and more on the manner of implementation.

For policymakers, the test is to enforce discipline without drowning projects in compliance burdens. For investors, the reforms signals both opportunities and responsibility. The door is open for greater private participation, but only for projects that can withstand financial, technical, and regulatory scrutiny without the crutch of sovereign guarantees. This could ultimately filter the market in favour of serious, well-capitalised players and encourage stronger project structuring from the outset.

Looking ahead, the guidelines could serve as a template not only for federal projects but also for states seeking to harmonise PPP practices and attract private capital. If faithfully implemented, they could catalyse a new wave of infrastructure financing in Nigeria. If not, they risk being remembered as another well-intentioned reform that faltered in execution.

Footnotes

1 ICRC Guidelines 2025 https://www.icrc.gov.ng/icrc-guidelines2025/

2 Paragraph 2.1.2 PPP Regulatory Notice-August 2025

3 Paragraph 3.2 PPP Regulatory Notice

4 Paragraph 3.3 PPP Regulatory Notice

5 Paragraph 3.7 PPP Regulatory Notice

6 Project Approval Board Governance Structure and Functions Notice

7 Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Project Financial Model Guide

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.