This article examines the ruling of the Supreme Court in Morgan Stanley and the ramifications of that case for the interpretation of the treaty article on permanent establishments and the attribution of profit to a permanent establishment in an international context. Other Indian court cases that shed light on these issues are also considered.

1. Introduction

The concept of a permanent establishment (PE) is one of the most critical issues in treaty-based international tax law. This is true because virtually all modern tax treaties use the PE as the main instrument to establish a jurisdiction to levy tax over unincorporated business activities of a foreign enterprise in the source country. A foreign enterprises profits from its unincorporated business activities in the source country are taxable only if that enterprise has a presence by way of a PE in that country. Art. 5 of both the OECD Model Tax Convention and the UN Model Treaty defines the term PE, and this definition has been adopted by countries around the world in their many income tax treaties (treaties).

The Supreme Court of India recently delivered a landmark

judgement pursuant to a Special Leave Petition filed by Morgan

Stanley and Co (and a similar petition filed by the Indian tax

authorities) against the ruling issued by the Authority for

Advance Rulings (AAR). The AAR Ruling dealt with whether Morgan

Stanley & Co (USA) (MSCo) had a PE in India as a

consequence of the back-office operations it had outsourced in

India to Morgan Stanley Advantage Services (MSAS) and the

persons from MSCo who visit India.

This article will examine the ruling of the Supreme Court and

its ramifications for the interpretation of the PE treaty

article and the attribution of profit to a PE

internationally.

The goal of income tax treaties is universally to encourage international trade and commerce by avoiding double taxation, and providing certainty by clearly delineating the taxing rights of each jurisdiction. However, the interpretation of Art. 5 (the PE article) of a treaty has lately revealed that each treaty partner will zealously try to protect its tax base; thus, the borders of PE taxation have slowly but surely seen the influence of the source states (especially emerging economies) interpreting the article in a manner very differently to the traditional manner, as historically understood (i.e. favouring capital and technologically exporting countries, namely developed countries).

The dynamic changes in the business environment, especially with regard to communication and information technology advances, have made the world a global village, and thus strained and challenged the traditional concept of PE taxation. Although efforts have been made by the OECD to make the PE conditions more inclusive to absorb and reflect these changes, the methodology of doing business is evolving every day and thus the decision of the Indian Supreme Court may be an indicator in the days to come, of how the PE concept should be equitably interpreted in an offshoring of business activity. In the near future, the concept of a PE arising from a fixed place of business (fixed-place PE) will need to be interpreted more liberally in this context so as to be in tune with reality and acknowledge the jurisdiction where the offshoring of business activity is carried out.

2. Facts of the Case

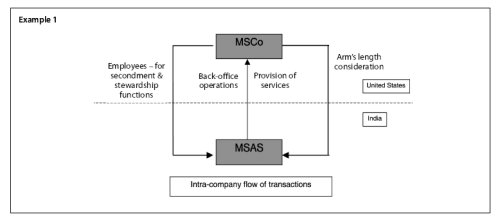

MSAS, an Indian company, and MSCo, a US company (the ultimate holding company of both these entities is Morgan Stanley International Holding Inc (US)), had entered into an agreement under which MSAS was to render services to MSCo in the nature of business process outsourcing activities the so-called offshoring phenomenon. See Example 1 above.

The business activities carried on by MSCo included the following: equity financing services and prime brokerage/fund services; investment banking; institutional data integrity; institutional securities marketing; compliance support; internal audit; planning company strategy; corporate action validation; netting project analysis; and equity research.

MSCo outsourced certain activities such as equity and fixed income research, dataprocessing, account reconciliations and information technology (IT) enabled services to MSAS. MSAS developed computer software (including customized electronic data, product or computer programs) which are of critical relevance for the various divisions of MSCo, such as equity research, the fixed income division, the equity financing service division and the investment banking division. MSAS provided research reports, data analysis, industry specific analysis, company-specific analysis and earning models of companies as part of an ongoing process to help various divisions of MSCo to formulate their business strategies and ensure that profits in the share portfolio and fixed income portfolio of the customers are enhanced, as well as to ensure that diverse business operations in the various divisions of MSCo (embracing the entire gamut of financial services) are carried out with optimum results. MSAS used the logo and brand name of Morgan Stanley MSAS was provided with customer- related material, including hardware, intellectual property rights, software, data licences, procurement and connectivity, and products developed by MSAS were the exclusive property of the Morgan Stanley Group. MSCo also seconded its employees to India for stewardship and management activities to ensure the quality of the outsourced services. Under the service agreement, MSAS was remunerated on the basis of a cost-plus markup by MSCo for providing these back-office services.

3. Authority for Advance Ruling

A ruling was sought from the AAR with regard to whether MSCo would be regarded as having a PE in India under the IndiaUnited States treaty in general, and specifically:

- whether MSCo has a PE on account of support services rendered by MSAS;

- whether MSAS should be regarded as constituting an agency PE of MSCo in India, given its economic dependence;

- whether MSCo should be regarded as having a service PE in India by virtue of its employees travelling to India to perform stewardship functions;

- whether MSCo should be regarded as having a service PE if it were to second its employees on secondment to India;

- whether the transactional net margin method (TNMM) is the most appropriate methodology for determining the arms length price, and whether the margin of operating costs plus a 29% markup, is arms length; and

- if the transactions between MSCo and MSAS are deemed to be arms length, whether any further income may be attributed to the PE.

Art. 5 of the IndiaUnited States treaty (the Treaty) provides as follows:

(1) For the purposes of this Convention, the term "permanent establishment" means a fixed place of business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on.

(2) The term "permanent establishment" includes especially:

- a place of management;

- a branch;

- an office;

- a factory;

- a workshop;

- a mine, an oil or gas well, a quarr)c or any other place of extraction of natural resources;

- a warehouse, in relation to a person providing storage facilities for others;

- a farm, plantation or other place where agriculture, forestry, plantation or related activities are carried on;

- a store or premises used as a sales outlet;

- an installation or structure used for the exploration or exploitation of natural resources, but only if so used for a period of more than 120 days in any twelve month period;

- a building site or construction, installation or assembly project or supervisory activities in connection therewith, where such site, project or activities (together with other such sites, projects or activities, if any) continue for a period of more than 120 days in any twelve month period;

- the furnishing of services, other than included services as defined in Article 12 (Royalties and Fees for included Services), within a Contracting State by an enterprise through employees or other personnel, but only if:

- activities of that nature continue within that State for a period or periods aggregating more than 90 days within any twelve-month period; or

- the services are performed within that State for related enterprise within the meaning of paragraph (1) of Article 9 (Associated Enterprises).

(3) Notwithstanding the preceding provisions of this Article, the term "permanent establishment" shall be deemed not to include any one or more of the following:

- the use of facilities solely for the purpose of storage, display, or occasional delivery of goods or merchandise belonging to the enterprise;

- the maintenance of a stock of goods or merchandise belonging to the enterprise solely for the purpose of storage, display, or occasional delivery;

- the maintenance of a stock of goods or merchandise belonging to the enterprise solely for the purpose of processing by another enterprise;

- the maintenance of a fixed place of business solely for the purpose of purchasing goods or merchandise, or of collecting information, for the enterprise;

- the maintenance of a fixed place of business solely for the purpose of advertising, for the supply of information, for scientific research or for other activities which have a preparatory or auxiliary character, for the enterprise.

(4) Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraphs (1) and (2), where a person - other than an agent of an independent status to whom paragraph (5) applies - is acting in a Contracting State on behalf of an enterprise of the other Contracting State, that enterprise shall be deemed to have a permanent establishment in the first-mentioned State if

- he has and habitually exercises in the first-mentioned State an authority to conclude contracts on behalf of the enterprise, unless his activities are limited to those mentioned in paragraph (3) which, if exercised through a fixed place of business, would not make that fixed place of business a permanent establishment under the provisions of that paragraph;

- he has no such authority but habitually maintains in the first-mentioned State a stock of goods or merchandise from which he regularly delivers goods or merchandise on behalf of the enterprise, and some additional activities conducted in that State on behalf of the enterprise have contributed to the sale of the goods or merchandise; or

- he habitually secures orders in the first-mentioned

State, wholly or almost wholly for the enterprise.

(5) An enterprise of a Contracting State shall not be deemed to have a permanent establishment in the other Contracting State merely because it carries on business in that other State through a broker, general commission agent, or any other agent of an independent status, provided that such persons are acting in the ordinary course of their business. However, when the activities of such an agent are devoted wholly or almost wholly on behalf of that enterprise and the transactions between the agent and the enterprise are not made under arms-length conditions, he shall not be considered an agent of independent status within the meaning of this paragraph.

(6) The fact that a company which is a resident of a Contracting State controls or is controlled by a company which is a resident of the other Contracting State, or which carries on business in that other State (whether through a permanent establishment or otherwise), shall not of itself constitute either company a permanent establishment of the other.

The AAR held as follows:1

- In order to constitute a fixed-place PE, an enterprise must undertake business through a fixed place of business (including machinery or equipment). Although MSAS was rendering servicesto MSCo, it could not be said that MSCo, by utilizing such services, undertook business activities through MSAS premises. Therefore, MSCo did not have a fixed- place PE in India. However, there are some noteworthy observations by the AAR in this ruling, especially in the current landscape of dynamic developments in the offshoring of business operations and processes which aim to take comparative advantage of costs, skill sets, knowledge, etc. The AAR noted that:

- the place of business of MSAS is a fixed place of business;

- however, no business of MSCo was carried on through the place of business of MSAS;

- thus, the relevant condition of carrying on business through the fixed place of business of MSAS is not present and, thus, Art. 5(1) of the Treaty is not attracted.

- Although the AAR did hold that MSAS was not a dependent agent of MSCo and thus did not create an agency PE under Art. 5(4) of the Treaty it notably stated that "the relationship of being a captive service provider, clearly demonstrates that MSAS is wholly and exclusively dependent on MSCo, and thus acts on behalf of MSCo / Morgan Group and is thus not an agent of independent status?2 However, as the conditions of Art. 5(4)(a)-(c) of the Treaty were not met, namely that MSAS does not conclude contracts on behalf of MSCo; does not stock goods for MSCo and thus does not deliver the same; or does not secure orders for MSCo, MSAS is not a dependent agent, and thus no agency PE is triggered under Art. 5(4) of the Treaty.

- MSCo employees seconded to India, including those performing stewardship functions, were actively involved in key managerial activities of MSAS and thus, MSAS would constitute a service PE of MSCo and Morgan Stanley group in India.

- As MSAS was remunerated in line with the arms length principle, no further income could be attributed to the service PE.

- The question regarding the appropriateness of the transfer pricing methodology for determining the arms length consideration and margin was not addressed, as it was deemed by the AAR to be outside its purview and jurisdiction.

4. Supreme Court Ruling

MSCo and the Indian tax authorities filed Special Leave

Petitions before the Supreme Court against the AAR decision

under Art. 136 of the Constitution. The tax authorities argued

that MSCo had a fixed-place PE, an agency PE or a service PE in

India and that thearms length remuneration paid to MSAS does

not extinguish the possibility of attributing any further

income to the PE. On the other hand, MSCo argued that the AAR

decision holding that it had a service PE in India, was

incorrect.

The Supreme Court held that:3

- MSCo was not carrying out any business activity in India. MSAS was rendering back-office services in India; such functions were considered as "preparatory or auxiliary" in nature under the Treaty. Thus, no fixed place of business existed under Art. 5(1) of the Treaty.

- MSAS did not conclude any contracts on behalf of MSCo and thus, did not have an agency PE in India.

- The purpose of rendering stewardship services was to protect MSCos interest by ensuring quality and confidentiality. Therefore, stewardship services rendered by MSCo did not trigger the existence of a service PE. Thus, on this issue, the Supreme Court deferred to the decision of the AAR and held in favour of MSCo.

- As regards secondment of MSCo employees, the Supreme Court (which referring to the function as "deputation and the individuals as "deputationists") held that MSCo did have a service PE in India. The primary reason that the Court deemed a PE to be triggered by such secondment was the lien that such secondees had on their employment with MSCo. It is only with regard to this issue that the tax authorities succeeded in their plea to the Supreme Court.

- The appropriateness of the remuneration paid by MSCo to MSAS for back-office services had been accepted by the Indian tax authorities, having regard to all the functions performed and the risks borne by MSAS in India. The profits attributable to a PE must be determined on the basis of the arms length principle. Such arms length remuneration must be worked out by taking into account all the functions performed and risks borne by the enterprise. Once the tax authorities accept that the PE has been remunerated on an arms length basis, after taking into account the functions performed and risks borne (which is a factual determination in each case), the profits attributable to the PE would be only such arms length profits and nothing further. However, should a transfer pricing analysis show that the PE is not remunerated adequately, taking into account the functions performed and risks borne, there would be a need to further attribute profits to the PE for the functions and risks that had not been considered. As in this particular case, the transfer pricing adequately represented the functions and risks, no further profits were attributable.

Subsequently Indian tax authorities filed a review petition with the Supreme Court, requesting to reconsider the above judgement. Recently the Supreme Court has dismissed this review petition. This means that the judgement of the Supreme Court is final and the law on this issue is, thus, settled.

Each of these aspects of the Supreme Court ruling is addressed below.

4.1. Fixed-place permanent establishment

4.1.1. Morgan Stanley case

Under Art. 5(1) of the Treaty (and the OECD Model Tax Convention), a fixed-place PE exists "when there is a fixed place through which the business of the enterprise has been carried on partly or wholly Art. 5(1) provides a definition of the term PE that brings out the essential characteristics of a PE in the sense of a distinct situs and a "fixed place of business Under the Commentary on the OECD Model Convention, the definition contains the following conditions:

- there is a "place of business i.e. a facility such as premises or, in certain instances, machinery or equipment;

- this place of business is "fixed i.e. it must be established at a distinct place with a certain degree of permanence; and

- the business of the enterprise is carried on through this fixed place of business. This usually means that persons who, in one way or another, are dependent on the enterprise (personnel) conduct the business of the enterprise in the country in which the fixed place is located. However, involvement of human beings is not determinative; the carrying on of anactivity is of prime importance. Thus, fully automatic machinery, computers, etc. could comply with this test.

From the above, it can be observed that a general definition of PE in the first part of Art. 5(1) postulates the existence of a fixed place of business, whereas the second part of Art. 5(1) postulates that the business be carried on through such fixed place.

The term "PE" was judicially recognized in India in the case of CIT v. Visakhapatnam Port Trust as requiring the following:

The OECD Commentary states that the term "place of business" covers any premises, facilities or installations used for carrying on the business of the enterprise, whether or not they are used exclusively for that purpose. A place of business may also exist where no premises are available or required for carrying on the business of the enterprise, and it simply has a certain amount of space at its disposal. It is immaterial whether the premises, facilities or installations are owned or rented by or are otherwise at the disposal of the enterprise. A place of business may thus be constituted by a pitch in a marketplace, or by a certain permanently used area in a customs depot (e.g. for the storage of dutiable goods). Again, the place of business may be situated in the business facilities of another enterprise. This may be the case for example where the foreign enterprise has at its constant disposal certain premises or a part thereof by the other enterprise.

In order for a foreign enterprise to be deemed to have a PE, one must consider the factual and functional analysis of the activities carried on by the enterprise. The activity need not be of a productive nature. Furthermore, the activity need not be permanent in the sense that there is no interruption of operations, but operations must be carried out on a regular basis. In addition, the business of an enterprise is carried on mainly by the entrepreneur or persons who are in a paid-employment relationship with the enterprise (personnel). "Personnel" includes employees and other persons receiving instructions from the enterprise (e.g. dependent agents). The powers of such personnel in its relationship with third parties are irrelevant. It makes no difference whether or not the dependent agent is authorized to conclude contracts if such person works at the fixed place of business.

In the Morgan Stanley case, back-office services had been outsourced by MSCo to MSAS in India as stated above. The Supreme Court did not consider it necessary to examine the first part of Art. 5(1), but rather looked directly at the second limb of Art. 5(1) and held that MSCo cannot be said to have a fixed-place PE in India under Art. 5(1) of the Treaty with regard to the back- office operations performed by MSAS, as the requirement of carrying on MSCos business through the fixed place was not satisfied. This is because the back-office functions were in the nature of preparatory or auxiliary activities, and thus fell in the negative list of activities as stated in Art. 5(3) of the Treaty. It may seem that the Supreme Court has not analysed the first part of Art. 5(1), i.e. whether MSCo had a fixed place of business in India through the offshoring of it various functions to MSAS. However, the AAR in its ruling clearly stated that "the place of business of MSAS is no doubt a fixed place.

Thus, it can be presumed that the Supreme Court examined in detail the nature of the functions performed by MSAS for MSCo, so as to negate the basic rule of the PE test in Art. 5, only because there was a fixed place of business for MSCo in India, through MSAS. Otherwise, there would be no need for the Supreme Court to have concluded that the activities of MSAS were "excepted activities" under Art. 5(3)(e) of the Treaty, and thus "MSAS would not constitute a fixed-place PE under Art. 5(1) of the treaty as regards its back office functions".5

The traditional approach to determining whether a foreign enterprise has a fixed-place PE in the source country is to look at the business activities carried on by the foreign enterprise itself in the source country. Treaties based on the OECD Model Convention and UN Model Treaty define a PE as a "fixed place of business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on The use of the word "through" means that the place of business is required to serve the business activities as the focal point of the business. The treaty definition of PE thus presupposes the performance of a "business activity The activities should be performed in, from or through the place of business. The connection between the place of business and the business activity of the enterprise need not involve human beings or any decision-making activity, as long as an activity is performed there. In order to apply the business-connection test, it is necessary to identify the party whose business activity is served by the place of business. The need for this test arises whenever the activity performed through the place of business may not be the business of the taxpayer, but of some other party.

In this case, the Supreme Court has gone beyond the traditional approach by observing and analysing the business activities conducted (i.e. back-office operations carried on by MSAS in India) for the purpose of determining whether MSCo has a PE in India. MSAS was providing services to MSCo and not otherwise.

In an offshoring scenario, business operations are outsourced such that there is an inextricable link between the activities of the service provider and the recipient of those services. In this case, the activities were wholly carried out by MSAS for MSCo, and the services were utilized by MSCo for its business. It was this link that probably caused both the AAR and the Supreme Court to believe that the premises of MSAS could constitute a fixed place of business for MSCo. It was also always the assertion of the tax authorities that MSCo should be determined to have a PE in India, as it intended "to carry out its business through MSAS in India" Thus, it is of utmost importance to understand the very basic nature of the offshoring business, whereby one analyses why MSASs premises was a fixed place of business of MSCo in India.

Another aspect of this decision that warrants consideration is the consequences if the offshored entity i.e. service provider had been carrying on front-office operations instead of back-office operations in India. The Supreme Court observed that in order to decide whether a PE existed, one must undertake a functional and factual analysis of each of the activities to be undertaken by the enterprise. The OECD Commentary has established criteria for a business activity that triggers the existence of a PE, including a"core business activity as opposed to an "auxiliary or preparatory activity The decisive issue for the Commentary is whether the activity "forms an essential and significant part of the activity of the enterprise as a whole All business activities that contribute to the business earnings of the enterprise are core business activities. Some activities, although undoubtedly parts of a business activity, are considered insignificant and are therefore specifically exempted under modern tax treaties (the negative list). The hypothesis for the preceding discussion is that the excepted-activity test looks at both the qualitative issue (i.e. the nature of the activity as essential or not) and its relative importance (significant) to the enterprise as a whole, which is a quantitative issue. Core business activities are those which increase the value of the enterprise, either as a going concern or based on the asset value. In the Morgan Stanley case, the Supreme Court held that back-office operations of MSAS are preparatory or auxiliary in nature and therefore, would not give rise to a PE.

In the case of front-office operations, they would form an essential and significant part of the activity of the enterprise as a whole, which contribute to the business earnings of the enterprise and, therefore, such operations may be regarded as core business activities. If the principal entity had outsourced to the service provider some of its main business functions which are substantive business functions and cannot be regarded as mere auxiliary or ancillary business functions, in such a case this could constitute core business functions falling under the ambit of Art. 5(1) of the Treaty, as an analogy of the Supreme Court ruling, and this could lead to the deemed existence of a PE.

According to the Supreme Court decision, where the activities of the offshored entity must be analysed in order to determine whether a foreign enterprise that out- sources its core business functions has a PE, this raises debatable issues in interpreting the PE article. The Supreme Court decision could mark a paradigm shift in the balance between service-exporting countries and service-importing countries. It remains to be seen how the Indian courts will rule on this issue in different contexts, and whether this issue would warrant consideration by the upper echelons of international tax jurisprudence!

Factors that could have been instrumental in the thought process of the AAR and the Supreme Court in treading such a path, i.e. analysing the functioning of the offshored entity (the Indian entity) and not that of the principal entity (the US entity) for purposes of evaluating whether the principal entity had a PE in India (the source state) include the following: the nature of the services arrangementbetween MSAS and MSCo, in which the intertwining of the process was established; the captive nature of the economic profile of MSAS; its total dependency on methodology of operation; and the generic control of MSCo.

However, the Supreme Court has placed great importance on the factual and functional matrix in determining whether a PE exists. Thus, it is this matrix which would be the determining factor, and due to various nuances prevalent in the dynamic nature of the off- shoring business, it is necessary to strike a note of caution. It would be premature to cloak all such arrangements with the same hue, as there could be essential differing economic parameters which would have a great bearing, for example, on third-party service providers.

It also bears consideration that the inherent nature of the offshoring business is dependent upon the link with the parent organization for the business to survive. Thus, the operational model of the entire industry would be at risk, which would never be in the interests of the economy of such countries (i.e. the service-exporting nations). Thus, a balanced approach and the analysis of this factual matrix, coupled with a rigorous transfer pricing analysis which would capture the real value contributed by the service provider to the income earning capacity of the service recipient (the most essential ingredient of the very business model), rather than merely seeking to accentuate the risk profile of this enterprise, so as to attribute equitably a fair compensation for service- exporting countries, could be a just methodology to deal with these complex issues. Under such an approach, neither state would be deprived of its rightful share of taxes, and thus, this could be the way forward.

4.1.2. Recent ruling in the Galileo case6

Recently, one issue raised before the Delhi Tribunal in the case of Galileo International Inc (Gil) was whether Gil could be said to have a fixed-place PE as well as an agency PE in India under the Treaty. In this case, Gil had entered into agreements with various participants (including airlines) to provide computer reservation system (CRS) services. In turn, it also appointed Interglobe, an unrelated company, as a distributor to market and distribute the CRS services to travel agents (subscribers) in India. Interglobe was to act as a sole and exclusive distributor of the Gils CRS services in India. Interglobe in turn entered into subscriber agreements with various travel agents to provide them access codes, equipment, communication links and support services.

The Tribunal noted that the CRS services which were the source of income, partially existed in the machines, namely various computers installed at the premises of the travel agents. In some cases, Gil had placed those computers, and in all cases the connectivity was installed by Gil through its agent. The computers so connected and configured, which could perform the functions of reservation and ticketing, were part and parcel of the entire CRS. Without the authority of Gil, such computers could not perform the reservation and ticketing portion of the CRS. The computers so installed could not be shifted from one place to another, even within the premises of the subscriber. Thus, GII exercised complete control over the computers installed at the premises of the subscribers.

The Tribunal held that this would amount to a fixed place of business for carrying on the business of Gil in India, and thus Gil has a fixed-place PE within the meaning of Art. 5(1) of the Treaty The Tribunal further held that using part of the CRS, the subscribers (travel agents) were capable of reserving and booking tickets. Thus, it could not be considered as "solely for the purpose of advertising" of the CRS. Further, as the operations in India directly contributed to the earning of revenue, these activities could in no way be regarded as preparatory or auxiliary in nature. Thus, the exception provided in Art. 5(3) of the Treaty7 would not apply and GII would be deemed to have a PE in India.

This Tribunal Ruling helps one to distinguish cases based on the nature of the activities, and when the negative list of activities may protect the foreign enterprise from having a PE.

4.2. Agency permanent establishment

In the Morgan Stanley case, the Supreme Court further observed that there was no agency PE because MSAS had no authority to enter into or conclude contracts on behalf of MSCo and the contracts were concluded in the United States. Only to the extent of back-office functions would the implementation of those contracts becarried out in India, and therefore MSAS does not constitute an agency PE under Art. 5(4) of the Treaty.

4.3. Service permanent establishment

Generally, an enterprise of one contracting state is said to have a PE in the other when such enterprise has a fixed place of business in that other contracting state through which the business of the enterprise is wholly or partly carried on. However, in the modern age where a business is not always carried on (particularly outside national borders of an enterprise) through a fixed place of business of its own, there is a deeming provision under certain treaties (especially the UN Model Treaty) like the service PE article, which deals with the situation where an enterprise provides services through its employees or other personnel in the source country. Thus, even in cases where the enterprise does not have a fixed place of business in another contracting state of the nature described in Art. 5(2) or otherwise, the enterprise could still be deemed to have a PE in the source country if certain conditions are fulfilled.

The rationale for the service PE clause finds justification in the modern, dynamic, ever-changing commercial arena. In todays age, it is apparent that significant value added activities can be carried on without a need for the traditional tools of operating a business, such as an office, or equipment. Thus, the fixed place of business test has been bypassed by the increasing mobility of commerce and business.

In such a scenario, the service PE fiction under a treaty is meant to protect the tax base of the source country in cases where a substantial contribution is made by the employees of the foreign enterprise. The profits derived from such activities would escape source state taxation, but for the service PE fiction. Thus, the service PE clause enables the source country to tax enterprises of the other country on the economic activities carried out in the host country above a threshold limit.

In this case, two activities were performed by employees of MSCo in India, namely stewardship activities and the work to be performed by secondees in India. There is no definition of stewardship activities under either domestic tax law or treaty provisions, with the exception of the 1979 OECD Transfer Pricing and Multinational Enterprises Report (the 1979 Report). According to the 1979 Report, stewardship activities cover a range of activities by a shareholder that may include the provision of service to other group members, for example, services that would be provided by a coordination centre.

In this case, the Supreme Court observed that stewardship activities are rendered in order to protect the interests of a customer/the principal. The stewards are not involved in day-to-day management or any specific services to be undertaken by the service provider A customer/principal is entitled to protect its interest with regard to both confidentiality and quality control. As MSCo had worldwide operations, it was entitled to insist on quality control and confidentiality from the service provider. The stewardship activities involved briefing of the MSAS staff to ensure that the output met the requirements of MSCo. These activities included monitoring of the outsourcing operations at MSAS. Therefore, MSCo, by performing stewardship activities through its employees, was in fact protecting its own interests, in terms of both confidentiality and quality control. In such a case, it could not be said that MSCo was rendering any services to MSAS. Accordingly, the Supreme Court held that stewardship activities would not fall under Art. 5(2)0) of the Treaty and could not be regarded as giving rise to a service PE.

With regard to secondment, it was noted that MSCo seconded its employees to MSAS and there was no transfer of employees from the payroll of MSCo to MSAS. The secondees performed certain services for MSAS, and they had a lien on their employment with MSCo. It was further observed that as long as the lien remained with MSCo, MSCo retained control of the secondees terms and employment. The Supreme Court specified a test such that where (1) the activities of a multinational enterprise involve its being responsible for the work of secondees and (2) employees continue to be on the payroll of the multinational enterprise or they continue to have a lien on their jobs with the multinational enterprise, a service PE could be deemed to exist.

Applying the above tests, the Supreme Court observed that MSAS makes a request whenever it needs the expertise of MSCos staff Secondees under such circumstances are expected to be experienced in banking and finance, and upon completion of their tenure, are repatriated to their job with the parent. In other words, they retain their lien on their jobs when they go to India. They lend their experience to MSAS in India as employees of MSCo, and accordingly, there is a service PE under Art. 5(2)0) under the Treaty.

From the above, it can be observed that to be deemed to have a service PE, the foreign enterprise must render services, and thus it must be responsible for the activities performed by the employees or the employees must be under its supervision and control. In short, the following conditions must be satisfied in order to be regarded as triggering a service PE in accordance with the decision of the Supreme Court:

- the multinational (foreign) enterprise continues to be responsible for the work performed by the employees; and

- the employees continue either (1) to be on the payroll of the multinational enterprise or (2) to have a lien on their jobs with the multinational enterprise.

The issue that could arise is whether it would be possible to argue that there is no service PE in the case where a multinational enterprise seconds its employees and also pays a salary to them (but recovers the same by way of a fee or charge of costs), but either is not responsible for their activities performed or the seconded employees are not under its supervision and control. The possible answer is yes. In this regard, reliance can be placed on the decision of the AAR in the case of Tekniskil (Sendrian) Berhard v. CIT,8 a case that involved a Korean-resident company, HHI, that was awarded a contract in India. In order to execute this contract, HHI required technical employees. Accordingly, it entered into a contract with a Malaysian company, TSB, under which TSB provided the required number of employees to HHI. The arrangement between TSB and HHI was as follows:

- TSB was to pay salaries and other costs to the employees;

- the employees were supposed to work under direct control and management of HHI;

- TSBs responsibility was to provide the right kind of employees. HHI was empowered to remove an employee on account of poor performance, etc.;

- TSB was not responsible for the work performed by its employees in India; and

- HHI was to pay charges to TSB towards the cost incurred

by TSB for the employees.

The AAR held that the activities of TSB did not create a PE

in India, and that in absence of a PE, business profits may not

be taxed in India. Art. 5(4)(a) of the India Malaysia

treaty9 (which deals with supervision) was not

attracted, as the employees were under the direct control and

management of HHI.

4.4. Definition of permanent establishment under domestic tax law

One more issue was addressed by the Supreme Court in the Morgan Stanley case. Under the Treaty, a PE is a fixed place of business through which the business of anenterprise is wholly or partly carried out.10 However, under Indian tax law, there is no definition of a PE except that provided in Sec. 92(F)(iiia) under the transfer pricing regulations. Under that provision, the term "PE" is defined as follows: "A permanent establishment includes a fixed place of business through which the business of the enterprise is wholly or partly carried on.

The issue raised before the Supreme Court was whether the definition of a PE under domestic tax law (as part of the transfer pricing regulations) is restricted only to fixed-place PEs. The Supreme Court analysed the definition of a PE under domestic tax law as compared to that under the Treaty. Circular 14 of 2001, issued by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (Apex Body administrating direct tax) concerning the taxation of business process outsourcing, clarified that the term "PE" has not been defined under domestic tax law, but its meaning may be understood with reference to an Indian income tax treaty Thus, the intention was to rely on the concept and definition of a PE as found in the applicable treaty However, the concept of a PE was introduced in domestic tax law as part of the statutory transfer pricing provisions by the Finance Act, 2002. In Sec. 92(F)(iii), the word "enterprise" is defined to mean " a person including a PE of such person who is proposed to be engaged in any activity relating to production..:. After having considered both definitions of a PE, the Supreme Court observed that the definition of a PE under the transfer pricing regulations is inclusive; however that is not the case under Art. 5(1) of the treaty, in which a PE is defined exhaustively The Court found that the intention of the parliament in adopting an inclusive definition of a PE was to include the concepts of a service PE, an agency PE, a construction PE, a software PE, etc.

Not all treaties contain a service PE clause and therefore, in such a case the issue arises as to whether it is relevant that a PE as defined under domestic tax law also includes a service PE. This issue is debatable and there is no clear answer However, under Indian domestic tax law, a nonresident may be governed by either the treaty or domestic tax law, whichever is more beneficial. Thus, where the applicable treaty does not contain a service PE article, the taxpayer cannot be said to constitute a service PE and thereby be exempt from the Courts rationale in the Morgan Stanley case, as the non-resident would be covered by the beneficial provisions of the applicable treaty.

Another issue that is relevant in the context of interpreting the service PE article of the Treaty (but which was not raised before the AAR or the Supreme Court) is that the deemed fiction of a service PE could not be attracted if the services rendered through employees or other personnel are taxable as fees for included services under Art. 12 of the Treaty11. In the Morgan Stanley case, neither the AAR nor the Supreme Court examined the taxability of such services under Art. 12 of the Treaty, although it would be possible for one to argue that such services could be regarded as "included services" under the Treaty, and thus not be covered by Art. 5 (the PE article) and would be governed by Art. 12 (fees for included services), and would require tax to be withheld under domestic law or the applicable treaty, whichever is more beneficial to the taxpayer.

For Part Two of this article click here.

Footnotes

1. 284 FIR 260.

2. 284 FIR 283, Para 24. (Emphasis added.)

3. 292 ITR 416.

4. 144 FIR 146 (AP) (emphasis added).

5. Emphasis added.

6 19 SOT 257

7. Under Art. 5(3), if a fixed place of business is maintained solely for the purpose of advertising, or for other activities which have a preparatory or auxiliary character, for the enterprise this fixed place will not be deemed to be a PE.

8. 222 ITR 551.

9. "An enterprise of one of the Contracting States shall be deemed to have a permanent establishment in the other Contracting State, if it carries on supervisory activities in that other Contracting State fbr more than six months in connection with a construction, installation or assembly project which is being undertaken in that other Contracting State".

10. Art.5(1).

11. See Art. 5(2)(l) Treaty

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.