- within Corporate/Commercial Law topic(s)

- within Corporate/Commercial Law, Energy and Natural Resources, Government and Public Sector topic(s)

BRIEF FACTS OF THE CASE

- M/s Xiaomi India Private Limited ('The Appellant') is a subsidiary company of M/s Xiaomi Singapore Pte Limited and is engaged in the business of distribution and trading of the consumer electronic products comprising of phones, IoT (Internet of Things) and lifestyle products such as televisions, accessories etc and related spares.

- An investigation was conducted by the DRI and based on the intelligence gathered, the authorities have alleged that Appellant has been allegedly evading custom duty by way of non-inclusion of royalty and license fee (paid by Xiaomi India under the exclusive agreements with the IPR holders) to the assessable value of goods imported.

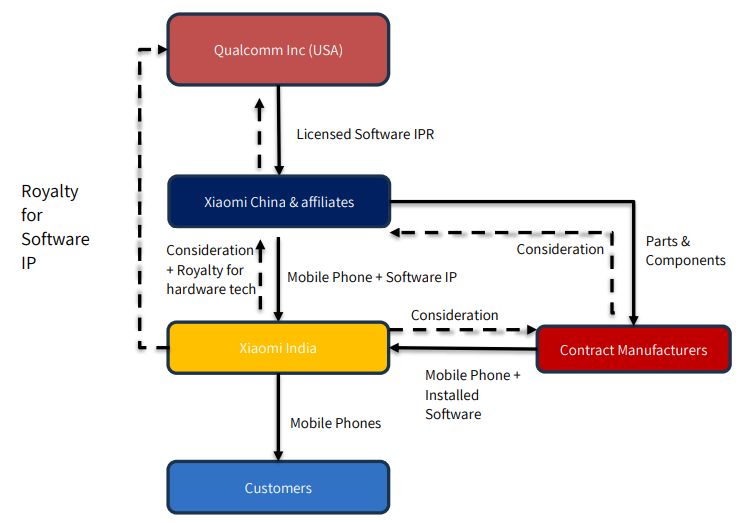

- The business operations of the Appellant are such that they do

not manufacture any goods in India. The consumer electronic goods

such as mobile phones, televisions and power banks are either

imported by the Appellant from Xiaomi China and their affiliates

('related entities') or got manufactured from the Contract

Manufacturers (CMs). Further, Xiaomi China and Qualcomm Inc, USA

have executed the following agreements for usage of Qualcomm

Licensed IPR and software.

- Subscriber Unit License Agreement (SULA) - Grants Xiaomi China and its affiliates a nontransferable license from Qualcomm to make, import, and sell subscriber units and components using Qualcomm's CDMA technology.

- Multi-Product Patent License Agreement (MPLA)- Provides Grants Xiaomi China and its affiliates rights under Qualcomm's licensed IPR to manufacture, import, and sell branded multimode terminals (3G/4G), with royalty obligations tied to sales turnover of finished devices.

- Master Service Agreement:Allows Grants Xiaomi China and its affiliates to receive and use Qualcomm's proprietary software designed for its chipsets, strictly for integration into licensed devices

- Based on the above, the Appellant directly pays royalty to Qualcomm Inc, USA for usage of Qualcomm licensed IPR in the mobile phones and electronic goods which are sold in India.

- In addition to the above, the Appellant has executed a License and Royalty Agreement (LRA) with the related entity in China for usage of MIUI operating software and proprietary hardware technologies against which royalty payments are made by the Appellant to the said related entity.

- The business arrangement of the Appellant with respect to procurement and distribution of the Mobile phones has been explained in the below pictorial chart.

- The DRI has observed that Appellant has paid royalties to Qualcomm Inc and Beijing Xiaomi (related entity) for import of finished mobile phones and components used by the CMs for manufacturing Xiaomi branded phones and has alleged that such royalty payments made by the Appellant is a condition of sale of mobile phones in India.

- Accordingly, the authorities have demanded duty from the Appellant on royalty payments made to Qualcomm Inc and Beijing Xiaomi (related entity) considering that effective control over the imported goods [including parts and components imported by the CMs] is exercised by the Appellant through restrictive agreements with the CMs.

- Whether the Appellant is the beneficial owner of the imported goods?

The Tribunal examined whether the CMs could be considered independent importers. The Appellant argued that CMs imported components on their own account, bore risk and ownership, and operated under globally recognized Electronic Contract Manufacturing (ECM) norms. They cited clauses in the Product Purchase Agreement showing transfer of risk and absence of agency. Revenue countered that the Appellant controlled pricing, resale, and intellectual property rights (IPR), and that CMs were bound by restrictive conditions, including exclusive supply to Xiaomi India and reimbursement of taxes. After analyzing the agreements and industry practices, the Tribunal held that the CMs did not enjoy full ownership rights or autonomy. Their role was akin to job workers, with the Appellant exercising dominant control over imports and manufacturing. Therefore, CMs were not the true buyers and that Xiaomi India was the real beneficiary.

The Tribunal referred to Section 2(3A) of the Customs Act, which defines "beneficial owner" as any person on whose behalf goods are imported or who exercises effective control. Considering Appellant's control over pricing, licensing, and contractual obligations, the Tribunal concluded that the Appellant was indeed the beneficial owner.

- Whether royalty/license fees are includible in transaction value?

The Appellant argued that royalties related to post-import activities and standard essential patents (SEPs), was not specific to imported goods, and were paid after sale of finished phones. Revenue contended that royalty payments were a condition of sale under agreements with Qualcomm and Beijing Xiaomi, without which imports and manufacturing could not proceed. The Tribunal analyzed agreements such as SULA, MPLA, MSA, and LRA, which granted rights to make, import, and sell devices using licensed technologies. It was found that royalties were directly linked to imported goods and constituted a condition of sale, satisfying Rule 10(1)(c) of the Customs Valuation Rules, 2007. Therefore, royalties and license fees were addable to the assessable value.

AURTUS COMMENTS

Rule 10(1)(c) of the Customs Valuation Rules, 2007 mandates the inclusion of royalty or license fee payments in the transaction value of imported goods, subject to an important condition—that the obligation to pay such royalties or fees must arise as a condition of sale of the imported goods. Disputes in this area typically center on factual determinations, particularly whether royalty payments constitute a condition of sale, which is assessed based on the contractual terms agreed upon with related supplier entities.

This judgment not only addresses the traditional question of whether royalty payments are a condition of sale but also explores the concept of beneficial ownership and the corresponding liabilities of the beneficial owner regarding payment of customs duty.

Before 31 March 2017, the term 'importer' under Customs Law included the owner of the goods or any person presenting themselves as the importer. The Hon'ble Tribunal's decisions in Nalin Z Mehta v. CC, Ahmedabad [2014 (303) E.L.T. 267 (Tri.-Ahd.)] and Commissioner of Customs vs Maharashtra Eastern Grid Power Transmission Company Ltd [2023 (6) Centax 115 (TriBom)] clarified that an importer under Section 2(26) is the person who files the Bills of Entry for clearance and pays the applicable customs duty. Effective 31 March 2017, the definition of 'Importer' under the Customs Act was expanded to include the term 'beneficial owner,' as defined in Section 2(3A). A beneficial owner is any person on whose behalf goods are imported or exported, or who exercises effective control over such goods.

In the present case, the Hon'ble Tribunal, relying on restrictive clauses in the agreement, held that the Appellant was the beneficial owner of the imported goods since effective possession, ownership, and control remained with the Appellant or its related entities. Consequently, the Appellant was held liable to pay tax on royalty, even though the goods were physically imported by the Contract Manufacturers (CMs). It is interesting to note that the Tribunal at the inception of its evaluation brand the CMs as job workers by equating the functions and responsibilities of an Electronic Contract Manufacturer ('ECM') with a job-worker, which is inherently a supply of service. Typically, in all ECMs or contract manufacturing contracts, the goods are sold back to the brand owner or the licensed distributor of the brand owner. These clauses on exclusivity are to protect the OEM's brand and IP. These clauses do not automatically alter the nature of these contracts to service contract.

It is not in doubt from the terms of the contract between Zhuhai China and the CMs, that the ownership in the imported parts and components passed to the CMs on the import of these goods into India. The question was whether the subsequent mandate on the CMs to sell these goods to Xiaomi India [and no one else], and the pricing restrictions would create a deemed /constructive ownership in favour of the buyer, i.e., Xiaomi India. The Hon'ble Tribunal while assessing this question from the lens of 'beneficial ownership' as formulated for the purpose of black money and tax evasion, has ultimately gone on the premise that since as per the ring fencing clause ultimately the tax cost is to be borne by Xiaomi India, the intent of the parties was to pass off a service contract as a contract for contract manufacturing. A ring-fencing clause is placed in contracts to segregate risks and liabilities. In the present case Zhuhai China, took the ultimate responsibility of any risk of increase in duties owing to any valuation disputes.

The recovery mechanism then put in placed mandated Xiaomi India to reimburse the subsequent increase in these tax costs to the CMs. These clauses merely create a legal civil remedy in favour of the CMs to recover these costs which may arise due to factors that they are not responsible for and ability to rightly recover these costs as part of the value of the finished product. The legislative intent behind introducing this concept in customs law was to make the beneficial owner liable only when the legal owner is not available. This interpretation was upheld by the Hon'ble CESTAT, New Delhi, in Pawan Munjal vs Commissioner of Customs [Order No. C/50497/2022], which clarified that the deeming fiction under Section 2(3A) does not apply if the legal owner is identifiable and accessible.

In today's competitive market, businesses often maintain oversight across their supply chains to ensure consistent quality standards. The key issue is determining the extent to which authorities can exercise their powers to hold the beneficial owner liable for customs duty. If beneficial owners are to be made liable in every import transaction, then responsibilities such as filing the Bill of Entry, issuing commercial invoices, and preparing shipping documents in the name of legal owner becomes an empty formality with no legal relevance. Regarding the payment of royalty or license fees linked to imported goods, the Hon'ble Tribunal upheld the lower authorities' decision to include the royalty/license fee in the assessable value of the goods based on the following grounds, amongst others:

- Royalty was calculated as a percentage of sales turnover, which included the value of imported goods.

- Payment of royalty was essential for the functioning of mobile phones, without which the import of parts and components by the Contract Manufacturers (CMs) would serve no purpose.

In this case even though the royalty ultimate relates to the usage of the ultimate finished product, for the purposes of customs valuation, it would be relevant to evaluate whether the patent technologies can be connected to any specific parts and components and their functioning to merit addition of such royalties to the value of such parts.

The primary argument to defend the addition of royalty was to state that royalty has been paid under a portfolio/ whole-device licensing model, where royalty is calculated on the final sale price of the entire product rather than on the value of the individual components. In case of Standard Essential Patents (SEPs), it said that the patented technologies are not specific to any physical component but may be used in various areas like wireless communication, wired interfaces, power, charging etc.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.