For justice to be achieved, like cases should be treated alike. When a court is faced with two very similar cases, it should arrive at broadly similar outcomes. Consistency in sentencing - encompassing both the adoption of a consistent methodology as well as the achievement of consistent sentencing outcomes - is therefore crucial to ensuring a fair justice system.

In Tan Song Cheng v Public Prosecutor and another appeal [2021] SGHC 138, the High Court agreed with the prosecution that previous sentencing decisions under section 96(1) of the Income Tax Act lacked a consistent or coherent sentencing approach. As such, the High Court substantially endorsed the five-step framework proposed by the prosecution, transposed from the five-step framework in Logachev Vladislav v Public Prosecutor [2018] 4 SLR 609:

- Identify the level of harm and the level of culpability;

- Identify the applicable indicative sentencing range;

- Identify the appropriate starting point within the indicative sentencing range;

- Make adjustments to the starting point to take into account offender-specific factors; and

- Make further adjustments to take into account the totality principle.

In this Update, we elaborate on the framework and examine the factors to be considered.

Factual Background

Section 96(1) of the Income Tax Act ("s 96(1)") sets out the penalties for tax evasion, being triple the quantum undercharged and/or obtained, with a fine not exceeding $10,000 and/or imprisonment not exceeding three years.

Briefly, the Appellants had pleaded guilty in separate and unrelated proceedings before the same District Judge to charges under s 96(1). At first instance, the District Judge accepted and applied the sentencing framework proposed by the prosecution for s 96(1) offences. Both Appellants filed appeals against their sentences, seeking changes to the sentencing framework, and the appeals were heard together by the High Court as the issues at hand were substantially the same.

Sentencing Framework

The High Court substantially upheld the five-step framework accepted by the District Judge as set out above, and we delve into each step below.

Tax

(A) Identify the level of harm and the level of culpability

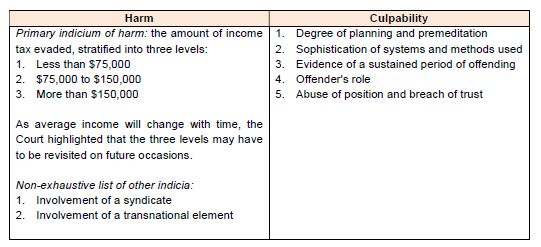

The level of harm and level of culpability should be assessed with reference to offence-specific factors as follows:

The Court rejected alternative approaches proposed by the Appellants, such as replacing the amount of income tax evaded (as the primary indicium of harm) with either the proportion of unreported income to reported income or the extent of restitution made. The former would permit offenders with higher incomes to avoid a higher sentence, while the latter would enable offenders to "escape" the consequences as long as they repaid the tax evaded.

(B) Identify the applicable sentencing range

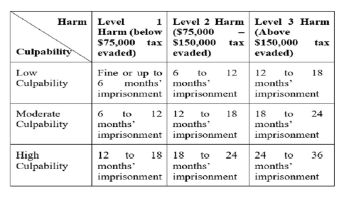

The Court adopted the indicative sentencing ranges per the below matrix:

With regard to determining whether to impose a custodial or non-custodial sentence, the Court noted that deterrence was the foremost consideration in sentencing for s 96(1) offences. While a custodial sentence is generally the norm, a non-custodial sentence by way of a fine could be imposed where the deterrent effect of the fine (capped at $10,000) would not be eclipsed by the mandatory treble penalty. For instance, in Chng Gim Huat v Public Prosecutor [2000] 2 SLR(R) 360, the mandatory penalty imposed was over $1 million; consequently, a $10,000 fine would have been of little deterrent effect.

(C) Identify the appropriate starting point within the indicative sentencing range

Under this step, the offence-specific factors examined under the first step should be re-examined. However the courts must be mindful to adjust the "severity" of the harm in relation to the other harm and culpability factors, in addition to the primary consideration of the amount of tax evaded.

(D) Make adjustments to the starting point to take into account offender-specific factors

Offender-specific factors comprise aggravating and mitigating factors which do not directly relate to the commission of the offence. They include:

1. Aggravating factors

a. Offences taken into consideration for the purpose of

sentencing

b. Relevant antecedents

c. Evident lack of remorse

2. Mitigating factors

a. A guilty plea

b. Voluntary restitution

c. Cooperation with authorities

An adjustment here may bring the sentence outside the indicative sentencing range, noting that such range is not set in stone. The total amount of tax evaded must also be considered at this step.

(E) Make further adjustments to take into account the totality principle

As a general rule, consecutive sentences should be ordered for unrelated offences. Under the totality principle, however, the court must then examine:

- whether the aggregate sentence is substantially above the sentences normally meted out for the most serious of the individual sentences committed; and

- whether the effect of the sentence on the offender is crushing and not in keeping with his past record and his future prospects.

Concluding Remarks

The Court's five-step framework provides welcome guidance and a clear shift towards improving the consistency of sentencing outcomes for s 96(1) offences. It is worth highlighting the prosecution's contention that the full sentencing range had not been utilised in precedent cases, with sentences clustering at the lower end of the range. In place of the imprisonment terms between one to six weeks imposed in earlier cases, the framework now provides for a clearer indication of how the full spectrum of possible sentences should be utilised, thus ensuring that future sentencing outcomes will be more aligned with Parliament's intentions.

First published - August 2021

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.