- within Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

This decision concerns an invention related to tracking and collecting data about containers. The distinguishing features of the main and the first auxiliary request were considered non-technical. Here are the practical takeaways from the decision T 1757/20 (Tracking containers/OWENS-BROCKWAY GLASS CONTAINER) of January 25, 2024, of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.01.

Key takeaways

A mere data transmission about the filling of a container is not sufficient for acknowledging a technical effect.

A possible final technical effect brought about by the action of a user cannot be used to establish an overall technical effect because it is conditional on the mental activities of the user.

The term "design of containers" is comparable to a sort of "configuration model", which belongs to information modelling, which is, as such.

The invention

The subject-matter of the application underlying the present decision is summarized as follows in the decision:

1.1 The invention relates to tracking and collecting data about reusable containers, see [0001], which are said to be designed and intended to travel repeatedly through an extensive distribution chain, see [0002].

1.2 Data regarding how a particular container travels through the distribution chain is either unavailable or limited, and as such, of little use to the container manufacturer, the initial customer of the container, or to other parties, see [0002].

1.3 The primary purpose of the invention is to track and collect data about containers as they travel through various points in a distribution chain using permanent and unique identifiers for each container, see [0003].

1.4 Paragraph [0060] mentions different usages of the collected data. One usage may be for the manufacturer as feedback to "learn how a particular container design performs" or as feedback "for modifying the design of a container", which is said to mean to strengthen, lighten or otherwise enhance or optimise container manufacture and/or design with the purpose of a longer lifetime or similar lifetime with reduced weight or increase speed or accuracy in filling. Another usage may be to charge customers for the containers supplied, in particular for implementing different pricing models based on the usage of the containers.

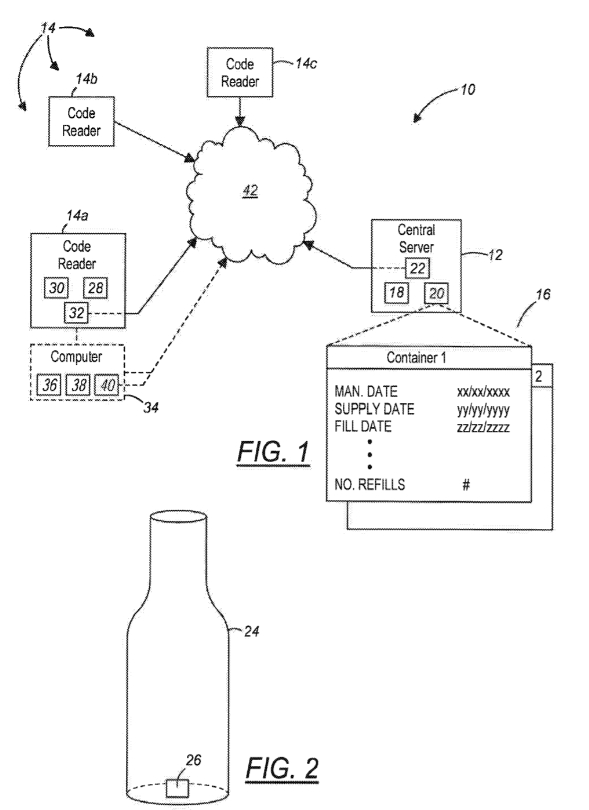

Fig. 1 and 2 of EP 3 345 135 A1

Claim 1

(F1) a method for container manufacturing and design, comprising the steps of:

(F2) designing and manufacturing containers (24) including forming the containers (24) and serializing each of the containers (24) with a unique machine-readable code (26) that is integral to and irremovable from the container (24);

(F3) using the machine-readable codes (26) to store data associated with the containers (24), including at least one of a date of container manufacture, a time of container manufacture, production facility data, or container quality data;

(F4) supplying the containers (24)

(F5) to a customer who fills containers;

(F6) receiving from the customer, data obtained from readings of the machine-readable codes (26) and

(F7) including data relating to the filling of the containers (24); and

(F8) using the data received from the customer relating to the filling of the containers as feedback for modifying a design of the containers (24).

The first auxiliary request replaces F8 of the main request by the following feature:

(F8) modifying a design of the containers (24) using the data received from the customer relating to the filling of the containers as feedback.

Is it technical?

D1 (WO 2010/009448) was considered as the closest prior art:

2.3 The appellant alleged that claim 1 differed from D1 by features (F5), (F6) and (F7) which reflect that the claimed containers are "reusable" and that there is a separate manufacturing and filling step, and further by feature (F8). D1 teaches that a container is manufactured and filled by the same entity, as shown in Figure 1.

Features 5, 6 and 7

The Board concludes that features (F5) to (F7) are known from D1 at the level of generality at which they are claimed.

Feature 8

2.5 As regards feature (F8), this feature defines the general purpose ("modifying a design"), but not how this is achieved and no active technical effect of how the design of a container can be improved is given. A mere data transmission about the filling of a container is not sufficient for acknowledging a technical effect. The present case is comparable to T 1234/17 where the present Board, in a different composition, found that the provision of a customised design for manufacturing does not alter the abstract nature of the customised design, see reasons, point 3.2. The Board in that case held that manufacturing an item based on a customised design was certainly a technical problem, but the provision of a specification was not sufficient to acknowledge technical character if the specification does not define how the manufacturing process is controlled in order to produce the item, or what components are to be used in the process.

The Board agrees with the examining division that feature (F8) defines a non-technical administrative constraint.

2.6 Irrespective of whether feature (F8) is interpreted as the possibility of using this data or as actual usage of this data, the usage can be interpreted in light of the description of the application in that the manufacturer learns from it and then mentally decides that a design should be changed. This situation is then similar to T 1741/08, reasons, point 2.1.6, which essentially concluded that a chain of effects, from providing information, to its use in a technical process, is broken by the intervention of a user. In other words, a possible final technical effect brought about by the action of a user cannot be used to establish an overall technical effect because it is conditional on the mental activities of the user, which might be a person skilled in the art of container design and manufacture.

2.7 The objective technical problem can be formulated as how to gather the necessary data relating to the filling of a container with the purpose of being able to modify a design of the containers, following the COMVIK approach (see T 641/00 – Two identities/COMVIK, OJ EPO 2003, 352). In this approach, the non-technical features can form part of the problem formulation.

2.8 The Board concludes that claim 1 lacks an inventive step (Article 56 EPC) over D1 in combination with common general knowledge, because the person skilled in the art would adapt D1 to implement the administrative scheme of using data relating to the filling of containers as a feedback for modifying a design of the containers.

2.9 The same reasoning applies to claim 1 of the first auxiliary request which only reformulates feature (F8), but does not add any further technical matter. The amendment may clarify that a container is modified based on feedback, as argued by the appellant, but it still does not define how this is achieved on a technical level. The term "design of containers" is comparable to a sort of "configuration model", which belongs to information modelling, which is, as such, not an invention for the purposes of Article 52(1) EPC, see T 1389/08, reasons, point 2.

As a result, the Board came to the conclusion that claim 1 of the main request and the first auxiliary request lack an inventive step over D1. However, the case was remitted to the examining division due to procedural reasons.

More information

The decision can be found here: T 1757/20 (Tracking containers/OWENS-BROCKWAY GLASS CONTAINER) of January 25, 2024, of the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.01.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.