Australia's renewables sector: the current state of play

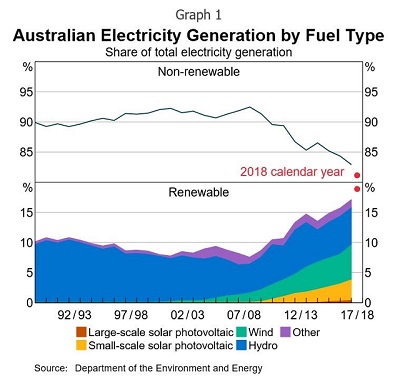

In 2019, it was reported that Australia's energy system is undergoing the transition to renewables faster than any other country in the world.1 In a report published by the Reserve Bank of Australia earlier this year, the marked growth in large-scale renewable energy projects in Australia was attributed to a combination of factors, including 'government policy incentives, elevated electricity prices and declining costs of renewable generation technology'.2

This is despite persistent criticism of Australia's transition from fossil fuel dependence towards cleaner energy sources.3 That criticism has largely centred upon the perceived absence of a consistent climate change policy at the federal level.4 The Renewable Energy Target (RET), Australia's key policy instrument for encouraging generation of electricity from renewable sources,5 is often cited as an example of a policy that has been hampered by politicisation.6 Under the RET, which was implemented in 2000, large scale renewable energy producers can create a tradeable large-scale generation certificate (LGC) for each MWh of power generated. The LGCs can then be purchased by energy retailers and other 'liable entities'. Under the RET, energy retailers are required to surrender a specific number of LGCs for the electricity that they acquire each year (or pay a charge in respect of any shortfall). In the RET model, it is the value of the LGCs, in combination with revenue received from the wholesale electricity price, that incentivises investment in renewable projects. The LGCs are necessary to account for the risk that, on its own, the wholesale electricity price will be insufficient to cover the long-run marginal cost of renewable technologies.7

After over a decade of steady take-up and bipartisan political support, a change in federal government in 2013 saw the RET become increasingly politicised. Between 2014 - 2015, the RET was the subject of a lengthy period of debate and review. During that period, private sector investment in large-scale renewable generation declined significantly, with no new greenfield renewable projects financed by the private sector.8 In contrast, after a bipartisan agreement was reached in May 2015, resulting in the implementation of a revised RET, the response was a substantial increase in growth and private investment in new renewable projects.9 In 2017, the Clean Energy Council (CEC) reported that the improved stability in Australia's renewable energy policy had contributed to unprecedented growth in new generation capacity in 2016 and a major uptick in investment in new projects.10

The example of the RET demonstrates that where bipartisan, long-term commitments are made (signalling increased political and regulatory stability), a marked increase in private investment in the renewables sector can be expected. Conversely, that momentum will likely stagnate in the face of ongoing political and regulatory uncertainty. As the CEC succinctly observed in their report on Australia's clean energy generation investment outlook: 'If the risk of major policy changes or government intervention in the market continues, investors and private capital will shift to other countries around the world where there is greater policy certainty'.11

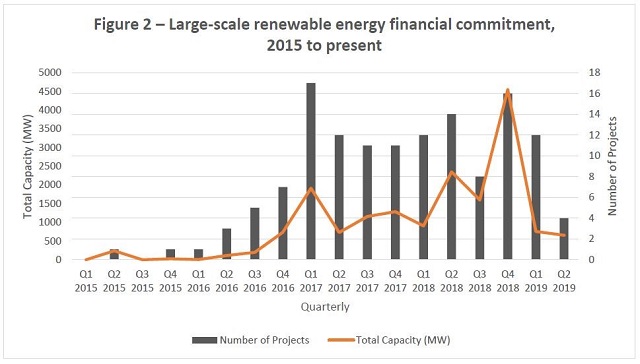

Looking to the future, there appears to be a widely-held view that the RET has served its purpose, and is unlikely to provide the necessary support to drive sustained investment in new renewable projects.12 Consequently, there is a perceived need for a renewed, long-term policy commitment at the federal level in order to boost investor confidence. In this respect, the CEC observed in 2019 that: 'Quarterly investment commitments in new renewable energy projects reached a high of over 4500 MW in late 2018, but has since collapsed to less than 800MW in each of the first two quarters of 2019'.13 This is illustrated in the graph below:

Source: Australia's Clean Energy Investment Outlook, Clean Energy Council (2019)

In addition to the need to stimulate investment in new projects, there is a pressing need for reform of Australia's underlying energy infrastructure. Existing investors in renewable energy production have reported that significant congestion on the power grid, which can produce volatile and unpredictable swings in transmission losses year to year, has been eroding plant profitability.14 The downside risk presented by grid constraints has reportedly prompted some investors to freeze future investment in the sector.15 As coal-generated (and to a lesser extent, gas-generated) power production is progressively retired, investment in the construction of new and augmented transmission infrastructure, as well as storage capability, will be critical. As noted in the Integrated System Plan for 2020 (ISP), there is an inherent asymmetry between 'the significant costs of early investment in large transmission projects, and the even more significant costs and risks of not having adequate resources available when needed to deliver affordable and reliable electricity.'16

Notwithstanding these immediate challenges, investors have continued to express confidence in the longer term outlook for the growth of the renewables market in Australia.17 Recent buzz around projects such as Tesla's South Australian Virtual Power Plant, supported by funding from the South Australian government and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, appear to have boosted optimism in Australia's clean energy transition. In the absence of renewed policy commitments at the federal level, state and territory governments have largely taken matters into their own hands, pursuing ambitious targets and implementing a range of 'technology pull' mechanisms.18 For example, in November this year, the New South Wales state government pledged to support the private sector to build $32 billion worth of renewable energy infrastructure by 2030. Earlier in the year, the Tasmanian government announced its plan for a 200 per cent RET, requiring Tasmania to effectively double its output of renewable energy from around 10,500GWh a year to 21,000GWh a year by 2040. It expects $7 billion to be invested in new renewable projects by 2030.

Against this backdrop, Australia remains attractive for investments in clean energy, and there continues to be a considerable inflow of foreign capital, particularly from overseas solar and wind developers. It was reported in July this year that 15 of the top 20 renewable energy developers in Australia are headquartered overseas.19 In the meantime, existing industry participants continue to grapple with how best to achieve the systematic reform that is needed to adapt Australia's existing energy infrastructure from centralised coal-fired generation to a renewable generation future. At a recent panel event, Audrey Zibelman (CEO of the Australian Energy Market Operator) likened this task to rebuilding an aeroplane while flying it.20 As the example of the RET demonstrates, maintaining a supportive and consistent political and regulatory framework will be crucial, if the current momentum in the sector is to be sustained.

Investment protections for renewable energy projects

The uncertainty faced by investors in the renewable energy sector over recent decades is not unique to Australia. It is largely a symptom of the long lead-time and capital-intensive nature of large scale renewable energy projects, resulting in a reliance - at least in part - on favourable regulatory frameworks and supportive government policies. That support can take many forms, including improvements in energy efficiency, the implementation of tradable certificate schemes (as adopted in Australia under the RET model), and the payment of fixed feed-in tariffs or market premiums to electricity producers from renewable sources.21

The success of regulatory or political measures designed to support renewable energy is as much dependent on the credibility of the public authority's long-term commitment as it is on the merit of the measures themselves.22 Indeed, the success of the RET in promoting renewable generation has been attributed to 'investor confidence in the longevity of the scheme, despite the various shortcomings associated with the scheme itself'.23 However, achieving regulatory certainty in the renewable energy sector is an elusive goal, because local, national and multi-national energy markets are continually evolving. The impact on investors was aptly summarised in the 2020 ISP (emphasis added):

The replacement of large-scale coal-fired power stations involves large-scale investments and deployment of new infrastructure, with long lead times and complex integration with the rest of the power system. Decisions on what and when to invest must be wise, for the consumer, the investor, and for the energy system itself. It is hard enough for investors to make such decisions within the complexity of the power system. A changing environment makes it even harder.24

As the experience in Spain and other European states has demonstrated, incentive schemes have proven to be prone to reduction and retraction as a consequence of state responses taken to stabilise the market; changes which can have a dramatic impact on the profitability of renewable projects. In this context, renewable energy investors in several European states have looked to the protections available to them in international trade agreements and treaties. The treaty most frequently invoked for this purpose is the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) - an international multilateral investment agreement which has the aim of promoting international cooperation in the energy sector.25 It seeks to achieve this aim by facilitating more secure, open and competitive energy markets, and encompasses four broad areas:

- foreign investment protections;

- non-discriminatory mandates concerning energy-related materials, products and equipment;

- resolution of investor-state disputes; and

- the encouragement of energy efficiencies.

Australia has signed, but not ratified, the ECT. As such, its provisions are not strictly binding on Australia. However, the investment protections set out in the ECT are broadly representative of the types of protections available to foreign investors under Australia's (binding) treaty commitments, which are discussed below. Article 10 of the ECT sets out a range of protections applicable to investments in the energy sector. These protections include the 'standard' protections found in most bilateral and multilateral investment treaties, such as the requirement to afford investments 'fair and equitable treatment' and 'constant protection and security', which confer protections which are no 'less favorable than that required by international law'.26 Under the ECT, the protections are applicable to any investment associated with an 'economic activity in the energy sector', provided that investment is made by an investor of one Contracting Party (referred to as the 'foreign investor') in the country of the other Contracting Party (referred to as the 'host state').27 The definition of 'economic activity in the energy sector' is broad. It includes the construction and operation of power generation facilities powered by renewable energy sources, while also encompassing investments in battery power and storage and energy efficiency, among others.28

The mechanism of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), which is a feature of the ECT and many other international investment treaties, exists to ensure that investment protections are not merely aspirational, but are capable of being enforced. ISDS enables foreign investors to bring claims directly against the host state, through international arbitration or conciliation, where the investor alleges that the host state has - through its conduct, or by implementing specific regulatory and political measures - breached one or more of the investment protections laid out in the treaty. Generally speaking, there is no ability for an investor (through ISDS) to prevent the host state's conduct, or to constrain the exercise of its political and regulatory mandate, no matter how dramatic or destructive its potential impact on the investment. However, ISDS does provide investors with recourse to seek compensation where it is found that the host state has committed a breach of its treaty obligations.

The most frequently invoked treaty standard is that of 'fair and equitable treatment'. It is, by design, elastic and capable of application to many different types of conduct. It has also provoked the most controversy, because of the inherent tension between (on the one hand) assuring a basic standard of predictability and stability to an investor, and (on the other) the right of host states to pursue their own regulatory policies in the public interest:

Many of the modern arbitral awards have been concerned with the determination of the appropriate boundary between two potentially conflicting values: a legitimate sphere for State regulation in the pursuit of public goods on the one hand (even if it may result in a loss of economic benefits to those subject to the regulation); and the protection of private property from State interference on the other.29

In ISDS, whether the host state's conduct is in breach of the relevant treaty standard is not a question of the legitimacy of the conduct by reference to domestic standards (although that may well be a relevant consideration). Rather, the treaty itself forms the basis for the parties' applicable rights and duties, and it must be applied and interpreted against the background of the general principles of international law. This makes sense, recalling that the purpose of investment protections being enshrined in international treaties is to allow the investor to challenge state conduct (be it the exercise of its executive, legislative or judicial function) that is arbitrary, unfair, or otherwise falls foul of international standards. If such conduct has occurred, one can readily see why seeking recourse domestically would be problematic. Therefore, the availability of direct arbitration between the investor and the host state, in an international forum that the host state does not control, is necessary to give investment protections (like the fair and equitable treatment standard) teeth.

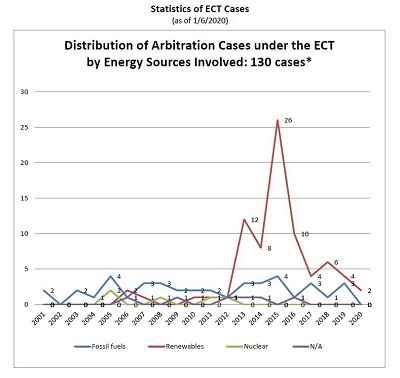

There are numerous examples of how the investment protections set out in the ECT have been invoked through ISDS where political or regulatory changes have eroded the profitability of renewable energy projects. Indeed, available data suggests that of the ISDS claims initiated under the ECT to date, approximately 60% (78 of 131) are claims made by investors in the renewable energy sector.30 The dramatic increase in ISDS claims initiated by renewable energy investors under the ECT over recent years is illustrated below.

Source: Statistics of ECT Cases (as of 1/6/2020), Energy Charter Secretariat (2020)

A recent case which is illustrative of these types of claims is that of Cube Infrastructure Fund SICAV and Others v Kingdom of Spain.31 The factual background, at a high level, is as follows: Between 2008 and 2012, the claimant investor, Cube Infrastructure (Cube) made investments in Spain's photovoltaic and hydroelectric sectors. These investments were alleged to have been made in reliance on attractive tariff rate guarantees provided in a 'special regime' pursuant to Royal Decree 661/2007 (Special Regime). In response to pressing economic concerns, including a tariff deficit caused by an imbalance between costs to the system (relevantly, the subsidies payable to energy producers) and revenue from consumer payments, Spain subsequently made a number of amendments to the Special Regime. Cube alleged that the particular amendments at issue constituted a contravention of the 'fair and equitable treatment' standard. It was contended that Cube had relied on representations made by Spain that the regime would apply for a defined period. According to Cube, such representations were sufficient to foster Cube's legitimate expectations of a certain degree of certainty and longevity, and it was on this basis that Cube made its investment. Cube alleged that the subsequent amendments to the regime violated Cube's legitimate expectations in respect of its photovoltaic and hydroelectric investments.

On 19 February 2019, the Tribunal issued its decision on the merits. The Tribunal observed that the Special Regime was established with the overt aim of attracting investments, by holding out to potential investors the prospect that the investments would be subject to a set of specific regulatory principles that would, as a matter of deliberate policy, be maintained in force for a finite length of time.32 The Tribunal considered that, in the context of a highly-regulated industry, such regimes are plainly intended to create expectations upon which investors will rely; and to the extent that those expectations are objectively reasonable, they give rise to legitimate expectations when investments are in fact made in reliance upon them.33 The Tribunal found that under Royal Decree 661/2007, Spain had created such expectations. It was unanimously found that Spain had breached Cube's right under Article 10 of the ECT to fair and equitable treatment in respect to their investments in the photovoltaic sector, and by a majority in respect to their investments in the hydroelectric sector. Ultimately, the Tribunal ordered Spain to pay damages of EUR 33.7 million in compensation.

As Cube Infrastructure demonstrates, by offering investors a means to redress the adverse impact of regulatory or political changes (so far as financial compensation can do it), ISDS represents one way for renewable energy investors to mitigate the associated risks. The ECT has a proven track record in this regard. Out of all ECT cases that have been determined in favour of the claimant investor to date, the majority involved claims arising from a measure or measures that have negatively impacted a renewable energy project.34 The awards rendered in such cases are illustrative of the circumstances in which equivalent protections in other bilateral and multilaterals trade agreements may be invoked and enforced.

To what extent, and in what circumstances, could foreign renewable energy investors in Australia invoke investment protections?

Australia is a signatory to dozens of bilateral and multilateral investment agreements, which provide foreign investors with protections equivalent to those in the ECT (including the right to fair and equitable treatment) and the ability to access ISDS. These mechanisms are found in the twelve bilateral35 and two multilateral36 agreements to which Australia is a signatory. It is also relevant to note that on 16 November 2020, it was announced that Australia had joined 14 other states in signing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which has been described as the 'world's largest free trade deal'. Although there is no ISDS mechanism in the RCEP, it constitutes a landmark statement in favour of free-trade and multilateralism by the new Indo-Pacific trading bloc.

While Australian companies have successfully enforced the protections available to them under Australia's investment treaty commitments (in respect of their investments abroad), Australia has so far managed to shake off claims brought against it. The only claim made against Australia to date was that advanced by Philip Morris Asia in respect of the introduction of plain packaging for tobacco products. Australia successfully defended that claim on jurisdictional grounds.37

Given the steady increase of renewable energy investment in Australia (much of it by foreign investors), the pressing need for further investment in the new transmission and storage technologies, and the sensitivity of renewable energy projects to regulatory and political change generally, it is timely to consider in what circumstances the investment protections available to foreign investors in Australia may be invoked. The ECT claims raised against Spain and other European states offer important lessons in this regard:

- The apolitical nature of ISDS decisions: Where renewable energy investors have been successful, it is not because their projects have been given 'special treatment' or deemed so important as to outweigh the operation of the host state's sovereign right to regulate. Rather, the outcome is arrived at following a distinctly apolitical process. Throughout that process, tribunals are plainly concerned with the need to strike a balance between, on the one hand, the investors' desires for a fair and consistent regulatory framework and, on the other, the host states' mandates to implement legal and regulatory changes. This demands a nuanced application of the relevant investment protections, with due regard for the relevant political, economic and social factors at play. In this way, the broad (and on one view, vague) wording of the investment protections allows tribunals the flexibility to determine the appropriate standard of treatment owed to investors in each case.

- The consequences of the host state's commitment to investors: In considering whether there has been a breach of the 'fair and equitable treatment' standard, tribunals have considered whether - on an objective analysis - the host state actively fostered or instilled an expectation in the mind of the investor that its investment would be treated with a certain degree of stability. If the investment was procured on the basis of a specific promise or commitment by the host state (for example, that the host state would not make changes to a favourable regulatory framework, or that if it did, those changes would not impact the investment in question), the host state will likely be held to that promise. As the Tribunal in Cube Infrastructure observed, if the host state makes a representation that induces investment, it must either deliver on that representation or ensure that any adjustments do not significantly alter the economic basis of the investments made in reliance on that representation. This balancing act was aptly summarised by the Tribunal as follows:

A government has a clear duty to act in the public interest and to react as best it can to developments that demand a change in governmental policies that, for whatever reason, become unsustainable. But the duty to react as best it can requires that a government act in accordance with the legal commitments that it has made and the obligations that bind it. In this case, the scope for government action was circumscribed by the Respondent's obligations under the ECT, including its duty under Article 10(1) ECT to accord fair and equitable treatment to the Claimants' investment. The duty to accord fair and equitable treatment entailed an obligation not to defeat the basic expectations that had been created by the Respondent specifically in order to encourage the investments necessary to implement its policy on renewable energy.38

- The relevance of the public interest objective: In considering the specific act of the host state that has given rise to the claim (for example, the retraction or significant reduction of a guaranteed feed-in tariff) the public interest objective underscoring that act will be a relevant consideration. For example, in Charanne v Spain, the Tribunal considered the pressing need to limit the tariff deficit in the solar energy sector, which had been worsening year by year.39 However, this does not involve the making of a value judgment about the perceived necessity or quality of the regulatory measure in question. Rather, the measure is assessed through the lens of whether or not the investor, in the precise circumstances of each case (and taking into account the nature of any specific promise or commitment by the host state), ought to have expected it.

- The investor's duty to assess the regulatory landscape, including the likelihood of change: On the other side of the coin, tribunals have considered whether the investors' expectations were rigid and unrealistic, or allowed for reasonably foreseeable changes. Investors cannot eliminate the possibility that the host state will exercise its sovereign prerogative to implement new measures, or to increase the impact of existing measures, in accordance with a legitimate public interest objective.40 Since economic, environmental and social considerations are necessarily dynamic, an investor must be able to demonstrate that it exercised due diligence in appraising the landscape of its potential investment. In other words, the pursuit of stability must be largely driven by the investor's own efforts. In Cube Infrastructure, the Tribunal emphasised that investors were never entitled to expect that the regulatory regime would remain completely unchanged.41

- The limitations on an investor's duty to predict (and accept) change: Like Cube Infrastructure, the Tribunal in SolEs Badajoz v Spain considered the impact of changes to the Special Regime in 2013 and 2014, in addition to the original amendments that were made to the Special Regime in 2010.42 The Tribunal found that the 2010 amendments had an adverse impact on the claimant's revenue, but did not fundamentally change the key features of the Special Regime, nor were they disproportionate to the policy objectives of those measures (i.e. the reduction of the tariff deficit).43 Accordingly, the amendments were found not to be inconsistent with Spain's obligation to accord fair and equitable treatment to the claimant's investment. Turning to the subsequent amendments, the Tribunal observed that - even in the wake of the 2010 amendments - the claimant was entitled to expect that its solar plants would continue to benefit from the original Special Regime (albeit to a lesser extent), by receiving stable remuneration in the form of a feed-in tariff.44 However, the 2013 - 2014 amendments were found to have fundamentally changed the basic features of the Special Regime, exceeding the changes that the claimant could have reasonably anticipated when it made its investment.45 Accordingly, the Tribunal concluded that, by enacting the subsequent amendments, Spain violated the fair and equitable treatment standard. Similar reasoning was applied in Cube Infrastructure, where the Tribunal found that despite the existence of a 'climate of change', the investors were entitled to expect that the fundamental characteristics of the Special Regime would remain in place.46

Does the availability of ISDS in Australia make foreign investment in renewables more attractive?

It is often stated that the availability of ISDS reduces the cost of investing in countries with high sovereign risk on the basis that, by citing the existence of treaty protection, an investor may be able to negotiate more favourable terms with its lenders.47 This perceived benefit of ISDS was referenced in a report by the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties in the context of Australian investors making investment decisions overseas. The report noted that 'the inclusion of ISDS provisions in an agreement Australia is party to, makes it cheaper and more attractive for Australians to invest in that country'.48 Accordingly, it is common for the availability of ISDS to be cited as a tool to attract and maintain inbound capital flows, particularly for developing countries and emerging markets where risk is often higher and where there is considerable need for foreign capital.

However, the question of whether there is a causal link between the availability of ISDS under any international investment agreement and increased foreign direct investment has not been answered in any definitive way. It is even less clear whether Australia's commitment to treaties which include investment protections (and recourse to ISDS) makes Australia a more attractive prospect for foreign investors than it would otherwise be (and relevantly, the Australian government is presently conducting a review of its bilateral investment treaty program). It has been suggested that the availability of ISDS can be cited by investors to negotiate reduced risk premiums because of its potential to alleviate the financial consequences of regulatory or political uncertainty.49 However, there are no specific examples of ISDS provisions being invoked in claims against Australia (beyond the jurisdictional contest encountered in Philip Morris), and certainly no precedent with respect to ISDS claims by renewable energy investors in Australia. In the circumstances, it is difficult to make the positive assertion that the availability of ISDS in Australia offers renewable energy investors the kind of comfort that would sound in tangible financial benefits (such as reduced risk premiums).

That said, regulatory and political risk continues to impact the flow of foreign capital and technology into the renewable energy sector in Australia, and if treaty protections were not available at all, they could not be factored into a broader assessment of the risk associated with a potential project. At the very least, Australia's acceptance of ISDS-backed treaties demonstrates to foreign investors that its legal framework, as applicable to the prospective investment, is aligned with international norms and standards. There are enough examples of those standards being enforced by renewable energy investors in Europe, in a wide array of different factual and technical contexts, to provide investors with an understanding of what they are entitled to expect from host states. Similarly, the ever-growing body of case law in this field should be closely examined by state signatories - Australia included - who have committed to afford foreign investors a certain standard of treatment under international law. These case examples offer valuable insight into the importance of regulatory and political consistency in the renewables sector, which cannot be overstated at such a critical juncture in Australia's clean energy transition.

Footnotes

1 Blakers et al., (2019) "Pathway to 100% Renewable Electricity", IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics, Vol. 9, No 6, cited in the 2020 Integrated System Plan at pages 8, 10, 21.

2 Reserve Bank of Australia, Renewable Energy Investment in Australia (19 March 2020).

3 See, for example, Sydney Morning Herald, Australia shows how policy can stifle renewable energy future (26 May 2020): https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/australia-shows-how-policy-can-stifle-renewable-energy-future-20200526-p54wea.html.

4 See, for example, Climate Council, State of Play: Renewable Energy Leaders and Losers (November 2019): https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/CC_State-Renewable-Energy-Nov-2019_V5.pdf, page 5: 'Despite the need for increased ambition, the Federal Government is getting in the way of progress on renewable energy.'

5 References in this article to 'renewable energy' are references to the capturing of energy from sources that are naturally replenished on a human timescale, such as sunlight, wind, rain, tides, waves and geothermal heat (and not to other sources of non-fossil fuel energy, such as nuclear): Omar Ellabban, et al., (2014) "Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology", Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol 39, No 748, 749.

6 See, for example, AFR, Playing politics with the RET (7 September 2015).

7 Ally Bonakdar, Australia's Clean Energy Policy and Regulatory Framework - Can it Drive Investment tp Achieve Australia's International Climate Goals? (2018) https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/2809956/Masters-Thesis-Ally-Bonakdar-FINAL.pdf, page 21.

8 Ibid, page 18.

9 Ibid.

10 Clean Energy Council, Clean Energy Australia Report 2016 (May 2017).

11 Clean Energy Council, Australia's Clean Energy Investment Outlook (11 September 2019), page 4.

12 See, for example, Reserve Bank of Australia, Renewable Energy Investment in Australia (19 March 2020): 'The Australian Government's RET has been met by the recent increase in renewable electricity generation capacity (CER 2019a). LGC futures have declined to around $15/MWh in 2022 and may decline further as more renewable capacity comes on line (Mercari 2020). As a result, the RET is unlikely to provide much support for investment in renewable generation in the future.'

13 Clean Energy Council, Australia's Clean Energy Investment Outlook (11 September 2019).

14 AFR, Solar investors choke on $1b congestion hit (25 September 2019). See also: Clean Energy Council, Australia's Clean Energy Investment Outlook (11 September 2019), page 4.

15 AFR, Solar investors choke on $1b congestion hit (25 September 2019): '"The market in Australia that we are looking at as it currently stands is presenting some significant challenges for continued investment and at this stage we are on hold for new investment for wind and solar here," Justin Bailey, regional managing director for John Laing in Asia Pacific, told The Australian Financial Review from the Middle East.'

16 Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), 2020 Integrated System Plan (July 2020).

17 AFR, Foreign firms flock to Australian renewable energy (6 July 2020): 'Over the longer term, the market dynamic is also moving the right way. Australia is already one of the largest renewables markets in Asia-Pacific. So it's a good market - but to succeed you also need patience, expertise and a good platform," a spokesperson for Iberdrola said.'

18 Ally Bonakdar, Australia's Clean Energy Policy and Regulatory Framework - Can it Drive Investment tp Achieve Australia's International Climate Goals? (2018) https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/2809956/Masters-Thesis-Ally-Bonakdar-FINAL.pdf, pages 32 - 33, 49.

19 AFR, Foreign firms flock to Australian renewable energy (6 July 2020).

20 Clean Energy Council, Women in Renewables 'Resilience in Renewables' webinar, 12 November 2020.

21 Anatole Boute, "Combating Climate Change Through Investment Arbitration", 35(7) Fordham International Law Journal 614, 622 (2012).

22 Ibid.

23 Ally Bonakdar, Australia's Clean Energy Policy and Regulatory Framework - Can it Drive Investment tp Achieve Australia's International Climate Goals? (2018) https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/2809956/Masters-Thesis-Ally-Bonakdar-FINAL.pdf, page 55.

24 Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), 2020 Integrated System Plan (July 2020), page 26.

25 Energy Charter Treaty, 1994 O.J.L. 380/24 (ECT).

26 ECT, art 10(1).

27 ECT, art. 1(6). 'Economic Activity in the Energy Sector' is defined at art. 1(5) to mean an economic activity concerning the exploration, extraction, refining, production, storage, land transport, transmission, distribution, trade, marketing, or sale of Energy Materials and Products (with certain specified exclusions) or concerning the distribution of heat to multiple premises.

28 ECT, art. 1(5)(ii).

29 McLachlan, Shore, Weiniger, International Investment Arbitration: Substantive Principles (2nd edition) paragraph 1.49.

30 Available data on ECT cases published by UNCTAD (as of 31 July 2020): https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement.

31 Cube Infrastructure Fund SICAV and Others v Kingdom of Spain (Decision on Jurisdiction, Liability and Partial Decision on Quantum, ICSID, Case No. ARB/15/20, 19 February 2019) (Cube Infrastructure) https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10692.pdf.

32 Cube Infrastructure at [388].

33 Ibid.

34 Available data on ECT cases published by UNCTAD suggests that, out of 29 cases determined in favour of the investor, 16 were initiated by investors in the renewable energy sector. See: https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement/advanced-search#aplicable-iia. Any reference to an award decided in favour of the investor is an award in which the investor succeeded on the merits, in whole or in part, and was entitled to payment and/or compensation.

35 Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (ANZCERTA); Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA); Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA); Thailand-Australia Free Trade Agreement (TAFTA); Australia-Chile Free Trade Agreement (AClFTA); Malaysia-Australia Free Trade Agreement (MAFTA); Korea-Australia Free Trade Agreement (KAFTA); Japan-Australia Economic Partnership Agreement (JAEPA); China-Australia (ChAFTA); Australia-Hong Kong Free Trade Agreement (A-HKFTA); Peru-Australia Free Trade Agreement (PAFTA); Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA).

36 ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA); Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

37 Marina Kofman and Erika Williams, "Philip Morris Asia Limited v The Commonwealth of Australia (PCA Case No. 2012-12) Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, 17 December 2015", School of International Arbitration, Queen Mary, University of London International Arbitration Case Law: https://www.transnational-dispute-management.com/downloads/16363_case_report_philip_morris_v_australia_-_award.pdf.

38 Cube Infrastructure at [409] - [410].

39 Charanne B.V, & Construction Investments S.A.R.L v The Kingdom of Spain (Award [per unofficial English Translation by Mena Chambers], SCC, Case No. V 062/2012, 21 January 2016) at [535].

40 As the tribunal found in Philip Morris Brands SÀRL, Philip Morris Products S.A. and Abal Hermanos S.A. v Oriental Republic of Uruguay (Award, ICSID, Case No ARB/10/7, 8 July 2016) (Philip Morris v Uruguay) at [422], the requirements of the FET standard 'do not affect the State's right to exercise its sovereign authority to legislate and to adapt its laws to changing circumstances': https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw7417.pdf.

41 Ibid at [357].

42 SolEs Badajoz GmbH v The Kingdom of Spain (Award, ICSID, Case No ARB/15/38, 31 July 2019) (SolEs Badajoz v. Spain): https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10836.pdf.

43 Ibid., [449]-[453].

44 Ibid., [458]-[459].

45 Ibid., [459]-[463].

46 Cube Infrastructure at [354]-[360].

47 See, e.g., Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), ISDS as an Instrument for Investment Protection and Facilitation, AEC Policy Brief 28 (October 2019) https://www.apec.org/Publications/2019/11/ISDS-as-an-Instrument-for-Investment-Promotion-and-Facilitation; Lindsay Oldenski, What Do the Data Say about the Relationship between Investor-State Dispute Settlement Provisions and FDI?, Peterson Institute for International Economics (11 March 2015). https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-investment-policy-watch/what-do-data-say-about-relationship-between-investor-state; Matthias Busse, Jens Königer & Peter Nunnenkamp, FDI Promotion through Bilateral Investment Treaties: More than a Bit?, 146 Rev. of World Economics 147 (2010); Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, Costs and Benefits of Investment Treaties, Columbia University (March 2018) http://ccsi.columbia.edu/files/2018/04/Cost-and-Benefits-of-Investment-Treaties-Practical-Considerations-for-States-ENG-mr.pdf.

48 Parliament of Australia, Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Trans Pacific Partnership, Report No 165, [6.27] (David Quinlivan, Chairman, Planet Mining Pty Ltd) (November 2016).

49 Sam Luttrell, "Why ISDS is Good for Australia", 42(11) Brief 10, 11 (2015).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.