As South East Queensland and key regional areas continue to become more densely developed, the scope for disputes between developers and owners of properties adjoining developments is at an all-time high. One type of dispute which has the potential to significantly alter the nature or cost of a project, is where the developer requires access or use of an adjoining property in order to feasibly carry out the project but the adjoining owner is not cooperative.

The type of access required by developers in these scenarios can be either:

- permanent access, in the sense that the developer requires use of part of the adjoining property on a perpetual basis including after the development is complete, eg access via a driveway; or

- temporary access during the course of development only, eg the developer requires the ability to move construction trucks across the adjoining property, or to overhang a crane over the adjoining property.

|

When negotiations with the adjoining owner fail, the developer needs to consider what legal rights it may have in order to gain the access required. In Queensland, the 'statutory right of user' provisions in section 180 of the Property Law Act 1974 are the appropriate avenue for relief.

Statutory right of user – what is required?

Several applications for statutory right of user have recently been heard in the Supreme Court. Under the statutory regime, a developer may apply to the court for an order that an adjoining owner grant the right to use the adjoining land if the following requirements are made out:

- the right is reasonably necessary in the interest of the effective use in any reasonable manner of the developer's land

- the right would be consistent with the public interest that the adjoining land should be used in the manner proposed;

- the adjoining owner can be adequately recompensed if the right was to be ordered; and

- the adjoining owner has unreasonably refused to agree to the developer's request.

If the court is satisfied of these requirements, the right granted could be in the form of a permanent easement, a temporary licence or another type of right.

A recent example

The recent decision of 2040 Logan Road Pty Ltd v Body Corporate for Paddington Mews CTS 39149 [2016] QSC 40 has shed some light on what the developer needs to prove in order to satisfy these requirements, particularly in relation to the fourth requirement, ie that there has been an unreasonable refusal by the adjoining owner.

What happened?

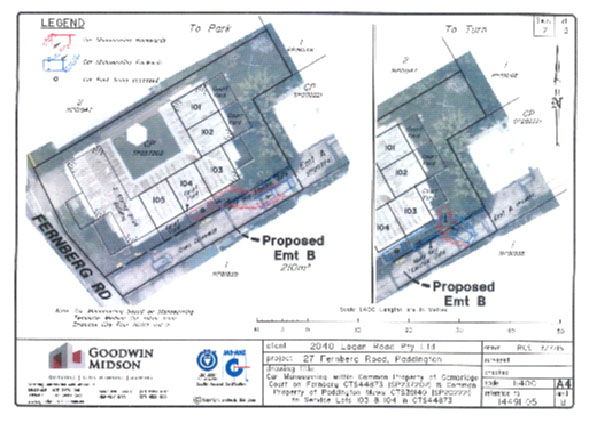

Lots 103 and 104 formed part of the Cambridge Court Community Titles Scheme. Those Lots did not have the use of any car parking bays. The owners of these Lots, wishing to enhance the value of their Lots, proposed to convert the small courtyards forming part of the Lots into car parking spaces. However, the only physical way that the cars could access the proposed parking spaces from Fernberg Road, would be via the concrete driveway, shown on the diagram as Proposed Easement B. That concrete driveway formed part of the neighbouring Paddington Mews Community Title Scheme. Paddington Mews comprised a series of townhouses at the rear of Cambridge Court, with the concrete driveway being its only means of access to Fernberg Road. Therefore, if the owners of Lots 103 and 104 wanted to have their parking spaces, they would need to make appropriate arrangements with the Body Corporate for Paddington Mews for the shared use of the concrete driveway.

The owners of Lots 103 and 104 requested that the Body Corporate for Paddington Mews agree to create Proposed Easement B so as to allow for vehicular access along the relevant part of the concrete driveway to the proposed parking spaces. As the Body Corporate for Paddington Mews refused, the owners commenced an action under section 180 of the Property Law Act.

The Court made the following findings in relation to the requirements of section 180:

- Was the Proposed Easement B reasonably necessary in the interest of the effective use of Lots 103 and 104? – While the Court accepted that the provision of the car parks and the Proposed Easement B would be desirable and convenient for the owners of Lots 103 and 104, the need did not rise to the level of 'reasonable necessity.' In particular, there was no evidence led by current residents of Cambridge Court as to the need for off-street parking. Further, it was found that at least 1 of the courtyards to be converted into a parking space was too small for the conversion to lawfully occur.

- Was the proposal consistent with the public interest? – Although the removal of cars from parking on busy Fernberg Road would be in the public interest, this would be outweighed by safety issues created by cars pulling out of the proposed new parking bays.

- Could the Body Corporate for Paddington Mews be adequately recompensed if Proposed Easement B was granted? – In principle, the Court accepted that the Body Corporate could be adequately compensated financially. However, it was not able to assess the amount of compensation without further detail being provided, including how the owners of Lots 103 and 104 would address the safety issues.

- Was the Body Corporate for Paddington Mews unreasonable in its refusal? – The case put forward by an applicant under section 180 must be 'clear and persuasive'. If an adjoining owner is not given appropriate detail as to the proposed right of user under section 180, then it will be difficult to establish that its refusal is unreasonable. Although this does not mean that every detail of the applicant's proposal must be finalised, or every associated approval (such as from the Council) obtained, in this case the Court found that the proposal put forward was insufficient in detail to permit proper consideration by either the Body Corporate for Paddington Mews or the Court. In particular, there was no proposal for addressing the safety issues, no evidence as to the need for off-street parking, no proposal for overcoming the difficulties in obtaining Council approval for the creation of the parking spaces and insufficient detail as to the removal of a power pole and associated underground services if Proposed Easement B was to be imposed.

Points to take away

It is important that developers carefully consider the 4 requirements for obtaining a statutory right of user and ensure that they can be satisfied before an application under section 180 is made. Focus should be given to the level of detail provided to the adjoining owner on the proposed use of their land. While developers might wish to 'test the water' with the adjoining owner at an early stage when only general details are available, if the adjoining owner is not cooperative the developer should make a more detailed submission, including as to how any difficulties might be addressed, to the adjoining owner before court action is commenced

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.