Key Point

- Recognising and debating the challenges with PPPs is a key feature to finding viable commercial solutions which enable the delivery of successful projects and value for money.

Development of PPPs in Australia

The development of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) in Australia was initially motivated by the desire of the States to develop public private infrastructure via the introduction of private finance, thus enabling the infrastructure to be brought on stream earlier than otherwise possible. Since then, however, the view has developed that the delivery and operation of public infrastructure by the private sector are more efficient than that possible by the public sector.

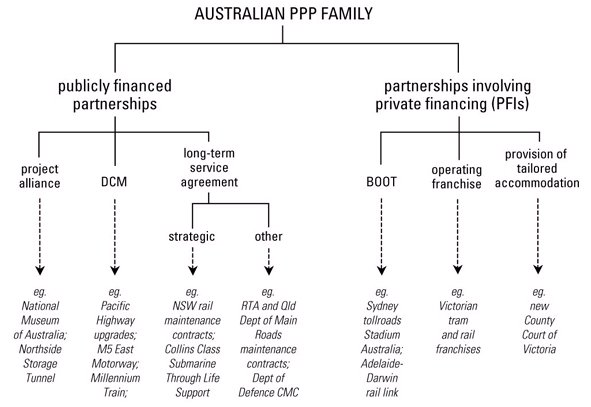

The concept of PPP can be likened to a broad church which covers public and private sector collaboration in a variety of forms.

The private sector has been involved in public infrastructure development for many years, commencing with the transport sector in the 1980s and moving from there into social infrastructure. During this time there was ad hoc development of policy by State governments, and very little development of policy by the Commonwealth, except in relation to the tax treatment of privately funded public infrastructure projects.

More recently, the State governments, influenced by developments in the UK, have each made moves towards more co-ordinated policy frameworks, commencing with the publication of Partnerships Victoria in 2001 and the subsequent release of policy and guidance materials by the other State governments and by the Federal government.

The policy of the State governments varies in its breadth and detail but has the following key features:

- The recognition that the decision to deliver a project by means of a PPP must represent value for money. Thus, a key issue is the establishment of clear and transparent mechanisms by which this can be achieved, such as the use of the public sector comparator;

- The development of private sector confidence in government delivery of PPPs. This remains a key issue for social infrastructure, even in the States of Victoria and New South Wales where there is a long track record of development of PPPs by government;

- An emphasis upon the valuation of PPPs on a whole-of-life basis, and the encouragement of PPPs for the purpose of delivering whole-of-life value for money;

- The encouragement of innovation;

- The identification, assignment and fair allocation of risks;

- The maximum utilisation of assets;

- The distinguishing of PPPs from privatisation;

- The recognition of the need for PPPs to be consistent with government objectives and the maintenance of delivery by government of key services;

- The establishment of clarity for the process;

- The maintenance of competitive tendering and probity; and

- The importance of transparency and accountability.

The broad church of PPPs can be usefully described as "The Australian PPP Family", as shown by the following diagram:

The challenges

Two challenges to PPPs are of particular note.

The first is the creation of a tendering environment which balances government's desire for certainty and for the maintenance of competitive tension thus avoiding deal creep, against the private sector's desire to reduce the cost of bidding. This also includes the establishment by government of clear requirements, while maintaining room for innovation.

The second objective is an efficient and sensible allocation of risk, involving:

- a balance between government wish lists and common business sense;

- the natural desire on the part of the private sector for a high comfort level; and

- the need for the private sector to develop real long-term business equity interests, rather than just short-term equity structured in a manner that can be easily sold down.

A key element in meeting these challenges is the effective management of the process. This involves:

- getting the documentation right, in an environment where the ground rules are known and acceptable to both the private sector and government; and

- clear communication between the parties, including early market engagement prior to shortlisting and bid, and then consultation between public and private parties throughout the bidding process in a manner which does not prejudice the maintenance of competitive tension.

Standardising contracts

Critical to the introduction of efficiency into the process is the standardisation of contracts. This has long been recognised as a desirable objective, but the lack of deal flow, particularly in social infrastructure, makes it difficult to achieve. The number of toll road projects successfully delivered in New South Wales has lead to a fairly standardised commercial approach to these types of projects, but the prospect of standardised PPP contracts Australia-wide is still a long way off. This is due to the fact that each of the States are at varying degrees of sophistication within the PPP market, there are tensions and jealousies between the States, and within States there are widely differing levels of experience between agencies. Furthermore, the Commonwealth has not moved very far in the PPP market to date.

However, at the initiative of the Victorian government, there has been a move towards greater consistency between governments, by means of the Partnerships Victoria standardised documentation process, and the establishment of the National PPP Council, consisting of representatives from each State and Territory and the Commonwealth Government, which held its first forum on 14 May 2004. As a result of the forum, the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance has begun the task of standardising risk allocation principles in commercial transactions and contractual provisions for PPPs, with the aim of producing a set of standard contractual clauses for use in Partnerships Victoria projects in early 2005.

The Partnerships Victoria standardised documentation process is an admirable initiative but its success will depend upon a sufficient level of deal flow in order to provide confidence to the private sector that various government agencies are in fact committed to, and able to use, standard documentation. There is also a need to recognise the fundamental commercial differences between social and economic infrastructure. Moreover, despite the benefits of standardisation, it is, and will continue to be important to tailor contractual documentation to meet specific requirements. It is dangerous to assume that the UK environment will prevail in Australia at any time soon.

Reducing bid costs

A final issue is the contentious question of bid costs. This has become a topic of recent debate in Victoria in the context of the Mitcham to Frankston Project. However, the debate in this context does need to recognise that some mega projects such as this one involve entirely different considerations for government and for the private sector than those arising in the context of smaller social infrastructure projects. It is not sensible to apply the same considerations to a large-scale, multi-billion dollar project such as Mitcham to Frankston as you would to a smaller project, such as a $20 million water treatment project for a local authority.

As mentioned above, the challenge is for government to maintain sufficient competition so as to avoid delay in contract close and deal creep following the preferment of a bidder. The large economic infrastructure projects, particularly toll roads, in Victoria and New South Wales have adopted approaches which have presented the opportunity for speed of closure and lack of deal creep - the envy of the UK market. For example, in the Mitcham to Frankston Project, despite only two consortia submitting proposals, competitive tension was created and maintained throughout the whole of the procurement process by engaging them both in thorough and detailed clarification discussions and negotiations prior to the award of the bid, and requiring them both to submit fully committed and signed project documentation at various stages of the bidding process, without knowing when the award would be made. These mechanisms do not lend themselves to small projects.

Key issues involved in meeting the challenge of bid costs include thorough engagement of the market before inviting expressions of interest; a simplified tendering process for low-value, uncomplicated projects; communication with bidders throughout the process; and serious consideration of contribution to bid costs.

Another matter of contention in this context is best and final offers (BAFOs). This concept is debated without a lot of regard for the fact that there are a significant number of variables to any complex project. There are significant commercial variables as well as very significant technical variables. It is thus rarely possible to have pure BAFOs, where remaining parties provide best and final offers on common technical and commercial bases. Rather, the issue for government is finalising evaluation with the certainty that the bids evaluated are those likely to be delivered at contractual close.

Given the differences between bids on both the commercial and the technical front, there is a lot to be said for maintaining competitive tension by a process similar to funded project definition by selected bidders similar to that undertaken in procurement as diverse as alliance bidding and major Defence contracting.

Conclusion

Significant challenges remain for the PPP market. As governments move further into the implementation of PPPs, the opportunity to meet these challenges increases. Recognising and debating these issues between government and industry will be the key to finding viable commercial solutions which enable the delivery of successful projects and value for money.

This article is an amended version of "Public-Private Partnerships: Family Improvement", originally published in Australian Chief Executive, May 2005 issue, CEDA, Melbourne.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.