- within Law Practice Management, Wealth Management and Insurance topic(s)

When deciding whether to approve share buybacks, corporate directors are well-advised to tune out the political. Rather, directors should fulfill their fiduciary duty and focus on the economics.

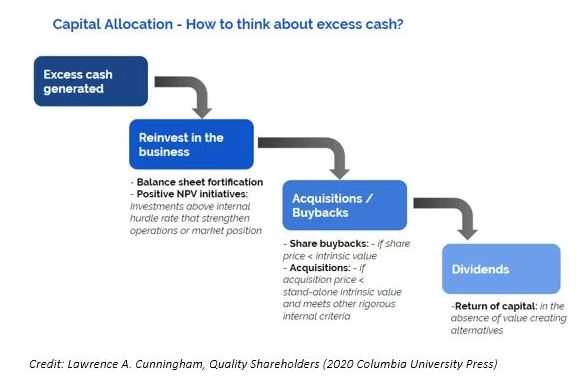

Share buybacks are one of several ways a corporation can deploy its capital. The first and primary use of capital is often to reinvest in existing businesses, from employee training and customer support to repaying lenders. An alternative use of capital is to acquire new businesses as stand-alone or tuck-in operations. After maxing out the value in these deployments of capital, the next obvious use is either to repurchase shares if they can be acquired cheaply or, if not, distribute the capital to shareholders as a dividend.

While such a capital allocation matrix is venerable, the element of buybacks was uncommon through the 1970s and 1980s, as dividends were the popular route for corporate distributions to shareholders. Back then, the buyback pioneers stood out, including Roberto Goizueta at Coca-Cola; Larry Tisch at Loews Corporation; Henry Singleton at Teledyne; and Kay Graham at The Washington Post Co. In that era, companies like those wrote today's textbook, repurchasing shares as a capital allocation exercise, when no better alternatives existed and price was below value.

By the late 1990s, buybacks had become a common practice across corporate America. Such proliferation raised a new concern: whether managers possessing superior valuation information exploit selling shareholders when buying at a discount. To address this, boards must insist that managers must provide shareholders with all relevant valuation information.

Since the early 2000s, a related problem appeared: executives sometimes become exuberant in preferring share buybacks to boost share price, thereby increasing the value of their stock options. Boards, who must approve buybacks, are advised to police against such self-interested behavior. While there is nothing wrong with boosting the stock price, the buyback should be used only if other uses of capital have been optimized and the existing share price is low.

In the 2020s, with buybacks rising to record levels, they are criticized by progressive politicians as allocating more corporate capital to shareholders that they would prefer to be deployed to invest in employees, customers and other constituents. It is in this context that share buybacks have become a political football in a game where neither sides' players are experienced in corporate capital allocation as directors or officers. Boards properly applying traditional capital allocation discipline already prioritize reinvesting in the business, as well as making valuable acquisitions, before considering either buybacks or dividends.

In short, as the history and economics of buybacks confirms, buybacks are never always good or always bad. They are good when effected at a price below value, when chosen without personal priorities of executives playing a role, and when consistent with optimal reinvestment in the business or compelling acquisitions. In such a complex and contingent environment, the recent imposition of a 1% tax on all buybacks appears to be an exercise in political expediency rather than rational economics. Warren Buffett in his most recent letter to shareholders wrote:

. . . When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demaogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive).

Such pointed language is rare for Buffett, whose letters I have studied and published as a book, The Essays of Warren Buffett. My book includes 15 pages of Buffett's thoughtful analytical perspective on the topic. Perhaps the best of these for present purposes is the following, which I took from his 2016 letter:

In the investment world, discussions about share repurchases often become heated. But I'd suggest that participants in this debate take a deep breath: Assessing the desirability of repurchases isn't that complicated.

From the standpoint of exiting shareholders, repurchases are always a plus. Though the day-to-day impact of these purchases is usually minuscule, it's always better for a seller to have an additional buyer in the market.

For continuing shareholders, however, repurchases only make sense if the shares are bought at a price below intrinsic value. When that rule is followed, the remaining shares experience an immediate gain in intrinsic value. . ..

[T]here are two occasions in which repurchases should not take place, even if the company's shares are underpriced. One is when a business both needs all its available money to protect or expand its own operations and is also uncomfortable adding further debt. Here, the internal need for funds should take priority. . ..

The second exception, less common, materializes when a business acquisition (or some other investment opportunity) offers far greater value than do the undervalued shares of the potential repurchaser.

The upshot: share buybacks are part of an overall capital allocation matrix corporations invariably work through. They are neither always good nor always bad. Directors overseeing capital allocation processes should stick to their capital allocation frameworks and not be swayed by political grandstanding. Some might find useful the accompanying capital allocation flowchart taken from another of my books.

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global legal services provider comprising legal practices that are separate entities (the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are: Mayer Brown LLP and Mayer Brown Europe – Brussels LLP, both limited liability partnerships established in Illinois USA; Mayer Brown International LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales (authorized and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority and registered in England and Wales number OC 303359); Mayer Brown, a SELAS established in France; Mayer Brown JSM, a Hong Kong partnership and its associated entities in Asia; and Tauil & Chequer Advogados, a Brazilian law partnership with which Mayer Brown is associated. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of the Mayer Brown Practices in their respective jurisdictions.

© Copyright 2020. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.