- within Compliance topic(s)

In Millennium Pharmaceuticals v. Sandoz,1 the Federal Circuit reversed the district court's holding of obviousness of certain claims of Millennium-owned U.S. Patent No. 6,713,446 (the '446 patent), finding that the district court improperly applied the lead compound analysis and the inherency doctrine and clearly erred by rejecting objective indicia of non-obviousness.

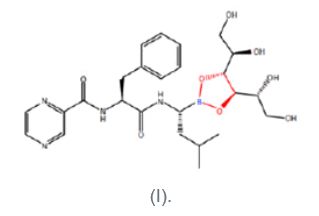

The disputed claims of the '446 patent2 are directed to Velcade®, a freeze-dried (lyophilized) formulation of D-mannitol N-(2-pyrazine) carbonyl-L-phenylalanine-L-leucine boronate (I) and methods of its preparation and reconstitution. Velcade is Millennium's oncology product prescribed for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. Compound (I) is a mannitol ester of bortezomib. The portion of the molecule depicted in red below identifies the ester linkage between bortezomib and the mannitol sugar.

Claim 20 is representative of the claims on appeal:

- The lyophilized compound D-mannitol N-(2-pyrazine) carbonyl-L-phenylalanine-L-leucine boronate.

While bortezomib exhibited efficacy against various cancers, it never achieved FDA approval because of its instability and insolubility. Despite years of research, scientists were unable to solve bortezomib's problems with a liquid formulation. After failing to develop suitable liquids, the inventor of the '446 patent investigated a lyophilized formulation, eventually arriving at a process that used mannitol as a bulking agent. The resulting lyophilized product was dramatically more stable and soluble than bortezomib. The reason for the significant improvement was discovered to be the unexpected formation of the mannitol ester during the lyophilization process. This mannitol ester acts as a prodrug, converting to bortezomib upon administration to a patient.

In the district court litigation, it was undisputed that Compound (I) was a new compound with advantageous properties. But the district court concluded that Compound (I) was obvious because freeze-drying was a known process for formulating pharmaceutical compounds, mannitol was known to be used in freeze-drying and the prodrug inherently formed during that process. The Federal Circuit found the district court's analysis fatally flawed. In so concluding, the court focused its analysis not on whether the process of lyophilizing bortezomib with mannitol would have been obvious but on whether Compound (I) would have been obvious.

The Federal Circuit reasoned that while mannitol was a known bulking agent used in lyophilization – itself a known method of drug formulation – "[t]he prior art contains no teaching or suggestion of this new compound, or that it would form during lyophilization."3 The court further noted that there is "no reference or combination of references that shows or suggests a reason to make the claimed compound."4

The Federal Circuit chastised the district court for relying on "inherency" to invalidate the claims, even though "the ester is the 'natural result' of freeze-drying bortezomib with mannitol."5 The court noted the "high standard in order to rely on inherency to establish the existence of a claim limitation in the prior art in an obviousness analysis."6 In this case, the reliance on inherency amounted to hindsight by following the inventor's path instead of the path that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have followed based on the prior art. The district court's reliance on the inventor's path violated Section 103's admonition that "[p]atentability shall not be negatived [sic] by the manner in which the invention was made."7 As to the path that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have followed, the Federal Circuit observed that "[n]o expert testified that they foresaw, or expected, or would have intended, the reaction between bortezomib and mannitol, or that the resulting ester would have the long-sought properties and advantages."8

The Federal Circuit further ruled that the district court clearly erred in its examination of the objective indicia of unexpected results, long-felt need and commercial success. The court found overcoming the problems of bortezomib's instability and insolubility to be unexpected. The court rejected the district court's reasoning that the comparison of the claimed invention should have been to other bortezomib esters that, although suggested, were not disclosed, prepared or tested in the prior art. Because bortezomib was not a viable commercial product, the court also found clearly erroneous the district court's perfunctory reasoning that the invention did not meet a long-felt need and was not commercially successful.

Finally, although an earlier patent encompassed bortezomib formulations until it expired in 2017, leading Sandoz to argue that there was no "failure of others" because they were blocked by that patent, the court stated that the question of failure of others was not before it, because long-felt need, although related, is distinct from failure of others.9 That ruling suggests that the blocking patent rationale of Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2005) does not apply, at least to the secondary consideration of long-felt but unmet need.

Millennium Pharmaceuticals v. Sandoz thus has a number of useful rulings for countering arguments of obviousness based on a hindsight reconstruction of the invention by piecing together separate prior art elements using the claimed invention as a blueprint.

Footnotes

[1] Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Sandoz Inc. et al., 2017 WL 3013204 (Fed. Cir. July 17, 2017).

[2] Claims 20, 31, 49 and 53 were at issue in this appeal.

[3] Millennium, 2017 WL 3013204 at *4.

[4] Id.

[5] Id. at *3.

[6] Id. at *6 (quoting Par Pharm., Inc. v. TWI Pharm., Inc., 773 F.3d 1186, 1195-96 [Fed. Circ. 2014]).

[7] Id. at *7 (quoting 35 U.S.C. § 103).

[8] Id.

[9] Id. at *8 n.5.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]