BACKGROUND

The incorporation of complex environmental and climate impacts from business operations and supply chains into human rights impact assessments and governance models is proving to be a major challenge for businesses. Uncertainty about the precise scope of obligations to assess such impacts has meant that companies are struggling to assess environmental and climate impact in a systemic way, which exposes businesses to future liability under the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (the "CS3D" or "Directive"). There are notable exceptions – we have seen examples of cement manufacturers, food and beverages companies and forestry companies demonstrate a clear understanding of the environmental dimension, or "lens", but more generally, businesses need to gear up now to ensure they have in place defensible compliance strategies.

Much of the attention given to CS3D so far has focused on the "pure" human rights aspects of the Directive. In this briefing we shine a light on the obligations in CS3D as they relate to the identification and management of environmental and climate change risk. In doing so, we assess the intersection between human rights impacts and environmental impacts (including climate change). It should be noted though that not all environmental matters are elevated to being subject to the full force of the CS3D's due diligence requirements. Instead, the legislation is specific about sources of environmental law that apply.

In summary, there are three key areas of environmental matters which are in scope of the CS3D:

- General environmental requirements. These are set out in Part 2 of the Annex to CS3D: In overview, these cover biodiversity protection and protected species and flora, certain types of hazardous waste and the manufacture of certain types of hazardous products (e.g., ozone-depleting substances).

- Adverse environmental impacts arising from human rights abuses. These are set out in paragraphs 15 and 16 of the Annex to CS3D: In overview, these are "measurable environmental degradation" impacting food production, access to clean water and sanitary facilities, health and safety or ecosystem degradation arising from human rights abuses (e.g., the right to life or a good standard of health).

- Adverse human rights impacts arising from environmental harm. In overview, these are a residual category of human rights abuses where the environmental harm was "reasonably foreseeable" having regard to the economic sector concerned and the operational and geographic context, where there is direct harm to a protected right and the abuse is capable of being caused by a commercial operator.

We unpick this in more detail below.

What do you need to do? The CS3D came into force in the EU on 25 July 2024. Member States have until 26 July 2026 to implement it in national law. However, businesses are already drawing up compliance strategies and many businesses purport to adhere to the UN Guiding Principles which foreshadow many of the requirements of the CD3D. Given the clear direction of travel and potential exposure to human rights and environmental liabilities, we suggest that even businesses that are out of scope start to develop an environmental and human rights due diligence policy and procedures.

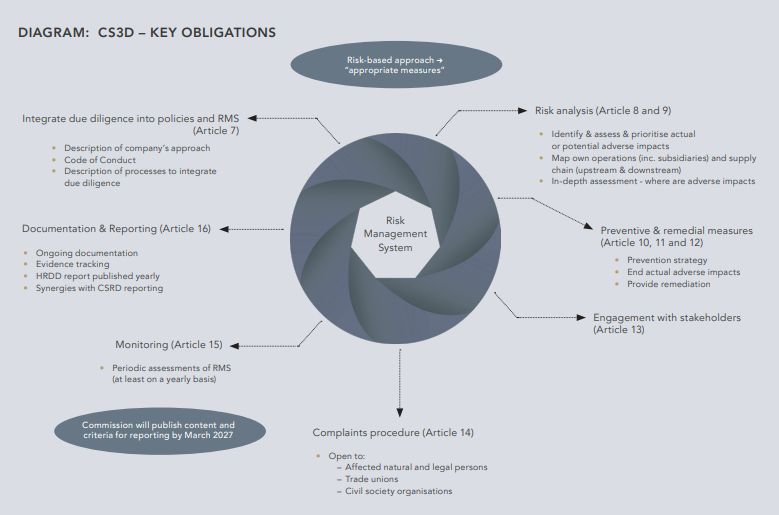

Our blog summarises the main requirements of CS3D, setting out which companies (both EU and non-EU) are within its scope, as well as an overview of the obligations to assess and manage human rights and environmental impacts across the supply chain. These are summarised in the diagram below:

Many businesses are already looking to build on their compliance with the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act or French duty of vigilance legislation1 in order to comply with CS3D. Broadly, general environmental requirements set out in the Annex to CS3D (which we refer to below) are aligned with the German supply chain law. They provide further clarity on the scope of adverse impacts on "human rights and fundamental freedom, health and safety of people and the environment" that the French duty of vigilance seeks to address. However, the CS3D goes beyond the existing German and French requirements.

While the CS3D is largely aligned with the duty of vigilance, it will substantially extend the number of in-scope companies, clarify their obligations and introduce administrative supervision and liability mechanisms. However, it is noteworthy that the civil liability mechanism foreseen under the duty of vigilance has already been relied on in pursuit of environmental objectives and such matters are currently the subject of pending litigation. Claims raised under the duty of vigilance have concerned topics ranging from climate change, deforestation, plastics use, water contamination, biodiversity and water resources.'

The German BAFA, the authority in charge of enforcing the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, has initiated investigations into the conduct of companies allegedly hampering access to clear drinking water and contaminating soil within Germany – which has raised questions about whether such conduct should not rather be prosecuted under the applicable German environmental protection regulations (which include criminal sanctions). In any event, it underlines that supply chain due diligence does have – besides the social aspect – a significant environmental angle to it.

In practice, businesses within the scope of CS3D have a legal duty to integrate environmental and climate impacts into their due diligence policies and risk management systems. When identifying their business risks and carrying out a risk assessment, they need to consider environmental and climate risks (extending across their chain of activities), and build an appropriate response into their documentation, reporting and preventability and remedial measures.

The starting point is to identify what environmental matters a business needs to be concerned with. This requires a detailed analysis of the CS3D. We have done this below.

DUE DILIGENCE – "ADVERSE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS" AND "ADVERSE HUMAN RIGHTS IMPACTS"

The Directive introduces the obligation for companies to conduct due diligence with respect to their operations, operations of their subsidiaries, and operations of their business partners in companies' chains of activities. This duty applies in respect of both "adverse environmental impacts" and "adverse human rights impacts." Both terms are defined at Art 3 of the Directive and both terms are relevant when designing a compliance strategy for assessing and managing any in-scope company's environmental and climate impacts (as well as those of its supply chain).

Moreover, "adverse environmental impacts" and "adverse human rights impacts" are defined by reference to the breach of either specific environmental obligations recognised in international treaties or human rights abuses recognised in international law arising from environmental harm or climate impacts.

It is therefore fundamental to consider environmental impacts as well as those in respect of human rights. The Directive does not elevate human rights concerns above environmental ones. And in any event, as we will see, the two categories of concerns are interlinked.

In addition, and to the extent that climate-related matters can be disassociated from general environmental matters, the Directive contains specific climate-related provisions. We review these in detail below. However, they include a requirement to put in place a climate transition plan. The actions set out in a climate transition plan will clearly be a significant source of mitigation of a business's climate impacts.

GENERAL ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS UNDER PART 2 OF THE ANNEX TO CS3D

Environmental protections in international law have developed in a piecemeal fashion. There is no overriding general treaty provision guaranteeing freedom from environmental harm, or defining what constitutes such harm.

Instead, individual treaties have been entered into in response to particular issues or events which the international community has regarded as tier one issues. These are principally environmental issues with a transboundary dimension.

A list of international environmental obligations relevant to the scope of the duty of diligence required by the Directive is set out at Part 2 of the Annex to CS3D ("Annex Part 2"). The relevant obligations broadly cover the following matters:

- adverse impacts on biodiversity;

- the import and export of endangered species of flora and fauna;

- the manufacture of, import and export of certain mercury-added products;

- the unlawful management of mercury waste;

- the production and use of certain persistent organic pollutants ("POPs") and the management of POP waste;

- the import and export of certain hazardous substances;

- the production, use, import or export of certain ozone-depleting substances;

- the transboundary shipment of certain wastes;

- adverse impacts on natural and cultural heritage;

- adverse impacts on certain protected wetlands; and

- shipping and marine pollution.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS:

These obligations are very broad.

However, they do not cover, for instance, climate impacts or pollution or emissions generally, nor any aspect of natural resource consumption, to name but a few potential "missing" categories of environmental harm. None the less, even on their own, these obligations mean that businesses will need to give serious consideration to a broad range of environmental factors, including "biodiversity", when reviewing the impacts of their operations and their supply chain. They will then need to comply with the gamut of Directive requirements, including taking steps to prevent, cease or minimise such actual and potential adverse impacts. For many businesses, this will present new challenges.

HUMAN RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND CLIMATE IMPACTS

The environmental implications of the Directive are not limited to the international obligations above.

In July 2022, the UN General Assembly resolved to recognise the right to a "clean, healthy and sustainable environment."2 However, this resolution is not legally binding and it should be noted, in the context of the CS3D, that the EU emphasised the political effect of the resolution and observed that it "lays the ground" for further action in this area – presumably, by the adoption at some point of a legally binding Treaty right to a clean environment.

That said, limited "derivative" rights to a clean environment have been legally recognised. So, for example, the right to life can be said to imply a right to a clean environment. This intersectionality between human rights and environmental protections is explicitly recognised in CS3D, notably in Recitals (36) and (89) and paragraphs 15 and 16 of the Annex to the Directive (discussed below). It results in two categories of human rights impacts with an environmental dimension that must be considered when designing a CS3D compliance strategy.

- The first category can be characterised as adverse environmental impacts arising from human rights abuses.

- The second category can be described as adverse human rights impacts arising from environmental harm.

Footnotes

To view the full article click here

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global services provider comprising associated legal practices that are separate entities, including Mayer Brown LLP (Illinois, USA), Mayer Brown International LLP (England & Wales), Mayer Brown (a Hong Kong partnership) and Tauil & Chequer Advogados (a Brazilian law partnership) and non-legal service providers, which provide consultancy services (collectively, the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are established in various jurisdictions and may be a legal person or a partnership. PK Wong & Nair LLC ("PKWN") is the constituent Singapore law practice of our licensed joint law venture in Singapore, Mayer Brown PK Wong & Nair Pte. Ltd. Details of the individual Mayer Brown Practices and PKWN can be found in the Legal Notices section of our website. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of Mayer Brown.

© Copyright 2024. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.