RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

PATENTS

High Court refuses to strike out an application for an injunction against infringing a drug patent

Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp and another v Teva Pharma BV and another, 15 March 2012.

The High Court has granted an interim injunction restraining sale of Teva's generic efavirenz product pending trial, in order to prevent patent infringement. The marketing authorisation for the generic product was applied for much earlier than normal before the expiry of the relevant patent and Teva refused to answer questions about the product launch. The case makes clear that a record of behaviour of a generic company (including the early launch of another generic product) is likely to be taken into account by the court when an application for an Interim injunction is made.

The patent, owned by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals Ltd, for a pharmaceutical preparation known as efavirenz (marketed as Sustiva), an antiretroviral compound, and supplementary protection certificate was due to expire in November 2013. Teva, a generic manufacturer, had obtained a marketing authorisation for its version of the drug and declined, when asked, to say when it planned to launch the generic preparation. The patent owners applied for an interim injunction pending trial to restrain Teva from infringing the patent. Teva applied for an order that the action be struck out.

HHJ Birss QC, sitting as a deputy High Court judge, held that the evidence supported the case for an interim injunction and that the action should not be struck out. Teva had sought the marketing authorisation some 22 months before the expiry of the relevant patent and SPC. The judge said it seemed obvious to him that "Teva must have obtained the marketing authorisation nearly two years in advance of expiry because they intend to launch before the [patent] rights have expired. It is not suggested that such a long period of time is normal and Teva do not say it is." That, combined with Teva having previously and surreptitiously launched a generic product in advance of [patent] expiry and the fact that Teva refused to answer questions about the launch when asked, supported the claimant's case that the launch of Teva's efavirenz preparation was intended to happen before the expiry date. The interim injunction restraining sale of Teva's generic efavirenz pending trial was granted (Teva's application to strike out was refused).

The Court of Appeal upholds a decision of the High Court concerning contraceptive formulation patents

Gedeon Richter plc v Bayer Pharma AG [2012] EWCA Civ 235, 7 March 2012.

In this recent action concerning contraceptive formulation patents, the Court of Appeal confirms the test to be applied when considering added matter (it will be added matter until it is clearly and unambiguously disclosed in the application explicitly or implicitly) and revisits the "obvious to try" test, including drawing attention to the dangers of hindsight in relation to obviousness.

The Court of Appeal recently upheld a decision of Floyd J that two patents for formulation of contraceptive pharmaceuticals were not invalid for added matter and were not obvious. The appellant, Gedeon Richter plc ("Richter"), sought revocation of two patents owned by the respondent Bayer Schering Pharma AG ("Schering"). Both patents related to immediate release formulations of the steroidal hormones drospirenone ("DSP") and ethinylestradiol ("EE"). The High Court held that the patents were not invalid for obviousness and were not invalid for added matter.

On appeal, upholding the decision of Floyd J, Kitchin LJ and Sir Robin Jacob decided that the judge had applied the correct test for added matter; the judge directed himself properly as to the law prior to considering whether there was added matter. Specifically, Floyd J set out the relevant test and emphasised four points: "..the fact that a claim covers something does not mean it discloses it; express disclosure in the patent of that which is implicit in the application does not amount to added matter; nevertheless, implicit disclosure is to be distinguished from matter which would be obvious to the skilled reader; and an eye needs to be kept on "impermissible intermediate generalisation"..". The Court of Appeal regarded it as "inconceivable that the judge did not have well in mind that subject matter will be added unless it is clearly and unambiguously disclosed in the application explicitly or implicitly, the so called strict comparison requirement". Further the judge expressly reminded himself of the need to draw a line between implicit disclosure and that which is obvious and so would have been well aware of the dangers of hindsight.

In relation to the finding of inventive step, the Court of Appeal considered the three published papers cited by the appellant and concluded that although the skilled person or team would have considered one of the items of prior art relied on by the appellant, the appellant did not adduce expert evidence to support its contentions that further evidence cited would have been read (even though the appellant had leave to call a medicinal chemist) and the judge was entitled to conclude that direct persuasive evidence was not available.

Counsel for Gedeon, the appellant, also advanced a case of "obvious to try". The Court revisited the significant limitations of the "obvious to try" test as set out in Conor v Angiotech [2008] UKHL 49, summarised as ".. the notion of something being obvious to try was useful as a means of establishing obviousness only in a case in which there was a fair expectation of success" and "..how much of an expectation would be needed, depended upon the particular facts of the case".

The Court held that the problem for the appellant in the present case was that there was really no or only the slightest expectation of success. "..It is all too easy to reconstruct with hindsight avenues that might have been pursued. The step from the published paper to the invention would have been more of a speculative jump in the dark than anything else." In addition, secondary evidence of the length of time it took the respondent to reach the invention, supported the conclusion of invention. Floyd J was entitled to make the evaluation "I think Schering's history provides a reasonable measure of support for non-obviousness".

Finally, in reaching his decision, there was another matter taken into account by Floyd J concerning the time taken for dissolution of the drug to take place in the stomach: there was no clear explanation of how the invention worked. Even now, it is not known why rapid dissolution of the drug takes place in the stomach. The judge, mindful of the dangers of hindsight, was correct to conclude that if something is inexplicable even after it is known, it is all the more unlikely to have been predictable (and thus obvious) before.

TRADE MARKS

High Court rules on claim for damages for the period following a disputed termination of an exclusive licence agreement

In this pro-longed and complicated dispute concerning a trade mark licence agreement (there were in fact two sets of proceedings between the parties), the High Court has ruled in favour of the Licensor in summary judgment applications concerning a claim for damages following alleged breach by the Licensee and subsequent disputed termination of contract by the Licensee, followed by a second (undisputed) termination by the Licensor.

The ruling confirms that a party to a contract may rely upon a breach which subsequently comes to light in order to justify an earlier termination of a contract (if the initial breach relied upon for the termination turns out not to be a breach after all). However, the ruling makes clear that such a breach may not be relied upon in a claim for damages against the Licensor because "..that alleged breach ...cannot be the cause of the termination and thus of the loss that flowed from the termination" (Roth J) (and summary judgment was given in favour of the Licensor on this basis preventing the Licensee recovering damages after the earlier termination date).

Leofelis SA ("Leofelis") was granted an exclusive licence agreement (the "Agreement") by two Lonsdale companies ("Lonsdale") in November 2002, for a period of six years from 1 January 2003, to use a series of trade marks (the "Trade Marks"), subject to payment of royalties, in relation to clothing and other goods in the then member states of the European Union, excluding the UK and Ireland. Under the terms of the Agreement, Leofelis was entitled to grant sub-licences of the Trade Marks, subject to the consent of Lonsdale. The Agreement provided for limited rights of termination and gave Leofelis the right to renew the Agreement for a further term expiring in 2014, subject to payment of further royalties.

Leofelis granted a sub-licence to an Italian company, Leeside srl, for Italy (the sublicence was extended to further European territories) and a further sub-licence to Punch GmbH for Germany, Benelux, Hungary and Poland. The German Punch licence was terminated in 2006 for non-payment of royalties.

Following a dispute between Lonsdale and Leofelis concerning the Leeside sub-licence and sales by Leeside in Germany, Lonsdale obtained an injunction in Germany preventing sales of Lonsdale branded goods there. The High Court in England subsequently ruled that the sub-licence to Leeside for Germany was valid and that therefore the injunction breached the terms of the Agreement. Leofelis by way of letter to Lonsdale, treated Lonsdale's action and continuing injunction to be a repudiatory breach of the Agreement, accepted such breach and terminated the Agreement with immediate effect (September 2007) (the first termination). Lonsdale did not accept the repudiation and demanded royalties. When Leofelis refused to pay, Lonsdale itself then terminated the Agreement (the second termination), in accordance with its terms, with immediate effect. The Court of Appeal then reversed the High Court's ruling concerning the legitimacy of the Leeside sub-licence for Germany, meaning that the German injunction was not a breach of the Agreement and so Leofelis could not justify its termination (i.e. the first termination). However, Leofelis then contended that there were other repudiatory breaches by Lonsdale which did justify the termination of the Agreement and on which Leofelis could properly rely (following Boston Deep Sea Fishing v Amsell (1888) 39 Ch D 339). Lonsdale acknowledged the Boston Deep Sea Fishing principle but said that this would not give Leofelis a good defence to Lonsdale's claim for damages. The question for the Court was whether Leofelis would be entitled to recover damages for the period after September 2007 (the date of the first (disputed) termination) since Leofelis had brought the Agreement to an end and was no longer a licensee after that date.

Concerning the 2005 proceedings, Roth J concluded that since the Agreement ended in late 2007 Leofelis could not have earned royalties after that date. The basis of damages for breach of contract was to put the innocent party in the same position that it would have been in had the breach not occurred. Leofelis claimed it was entitled to damages as a result, amongst other things, of the effect of sales (by a third party) of branded goods in Belgium (the "Belgian Sales") with the knowledge or consent of Lonsdale, in breach of the exclusivity terms of the Agreement. Leofelis also claimed damages in respect of lost royalty income in Italy, France, The Netherlands and Germany (the Belgian branded goods found their way onto the market in those territories and thus had an impact on Leofelis' royalty income there as well). Leofelis' claim for damages for the period after September 2007 amounted to Euros 26 million. However, the Agreement came to an end in September 2007 for reasons other than the alleged Belgian Sales. That conclusion was not affected by the question of whether the cause of the Agreement coming to an end was a separate and subsequent breach by Lonsdale. Awarding Leofelis damages for the period after September 2007 would provide Leofelis with a windfall. If Leofelis was itself in repudiatory breach in late 2007, then clearly it could not properly seek to recover damages for any loss of royalties after that period.

The issue of which party was responsible for the termination was a matter for the second (2009) set of proceedings, not the 2005 proceedings. Considering in turn the hypotheses that Leofelis was or was not in repudiatory breach, Roth J considered that the just and principled approach was to reflect that the Agreement came to an end in 2007 and then take account of this when addressing the question of which party was responsible for the financial consequences of the termination. Accordingly, Roth J concluded that the claim for damages after late 2007 was bound to fail and that summary judgment should be awarded to Lonsdale.

Concerning the second set of proceedings (2009), Roth J in his judgement made clear that he had not found the question before the Court altogether easy to resolve. He indicated that it was appropriate to go back to first principles:

"The measure of damages for breach of contract is to put the innocent party in the position that it would have been in if there had been no such breach. In this situation, if Y had not committed the repudiatory breach, the contract would still have come to an end as X decided to terminate it without knowledge of that breach by Y. X therefore should not be able to rely on Y's repudiatory breach as the grounds for recovering damages for the contract coming to an end, i.e. for loss caused by Y's non-performance of its primary obligations thereafter.

Leofelis submits with force that if that is correct, here it enables Lonsdale to benefit from having concealed its breach of contract concerning the SIA Licence."

Lonsdale had granted a licence (the SIA Licence) to a Latvian company, which it was alleged subsequently sold Lonsdale products in Leeside territories.

"Had Leofelis known about that conduct, it would have relied on it as a ground for terminating the Agreement in September 2007. That may be so in one sense. However, it is only an accepted repudiatory breach that brings a contract to an end. The unknown breach of the Agreement by Lonsdale was not accepted by Leofelis as a repudiation for the obvious reason that it was unknown. Therefore, that alleged breach, although its nature met the test for a repudiatory breach, cannot be the cause of the termination and thus of the loss that flowed from the termination. Put another way, Leofelis is not able to contend that if Lonsdale had not engaged in the impugned conduct regarding SIA, then the Agreement would have remained on foot such that Leofelis was in a position to earn continuing royalties from its sub-licences.

By the same reasoning, I consider that the terms of the letter of 28 September 2007 [the letter from Leofelis' solicitors to Lonsdale terminating the Agreement], which states "without prejudice to any other breaches" does not assist Leofelis. This lawyer's catch-all cannot alter the position in fact, which is that Leofelis terminated the Agreement irrespective of the SIA Licence or any circumstances surrounding it.

Viewed as a question of causation, therefore, I consider that the counterclaim to damages after 28 September 2007 must fail. Leofelis' position would not be improved by any findings of fact that may be made at trial. Accordingly, on the established principles governing summary judgment, it is appropriate to determine this matter in Lonsdale's favour. "

Roth J ruled that Leofelis' claim for damages should be limited to the period to September 2007 (the date of the first (disputed) termination by Leofelis), thus ruling out a large proportion of the damages claimed by Leofelis.

This ruling, decided in Lonsdale's favour, relates to summary judgment applications concerning Leofelis' claim for damages; the actions continue in the light of the decision. Permission to appeal has been granted to Leofelis.

COPYRIGHT

BT and Talk Talk lose their appeal over recent legislation introduced to tackle copyright infringement online.

Now that the Court of Appeal has rejected an appeal by Talk Talk and BT concerning judicial review of certain provisions of the Digital Economy Act 2010 alleged by Talk Talk and BT to be incompatible with European law, it remains to be seen whether enforcement provisions under the Act will be delayed and whether Talk Talk and BT will seek leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Last year, the High Court rejected claims by BT and Talk Talk that certain provisions of the Digital Economy Act 2010 (the "Act") were incompatible with European law. Permission to appeal was granted to BT and TalkTalk, on grounds covering four areas: that the contested provisions should have been notified to the EU Commission in draft pursuant to the Technical Standards Directive and were unenforceable for want of notification (ground 1); that the contested provisions were incompatible with the Electronic Commerce Directive concerning legal aspects of information society services (ground 2); that the contested provisions were incompatible with the provisions of the Data Protection Directive and the Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive concerning the protection of individual's personal data and protection of privacy (ground 3); and that the contested provisions were incompatible with the Authorisation Directive (ground 4).

The Act, which is aimed at reducing online copyright infringement, imposes obligations on internet service providers ("ISP"s) such as BT and Talk Talk, including obligations requiring ISPs to notify subscribers if their internet protocol addresses are reported in copyright infringement reports by copyright owners and to provide copyright owners with copyright infringement lists for subscribers if infringement reports exceed a certain level. Although the Court of Appeal rejected the appellants' grounds of appeal, the court did find in the appellants' favour in relation to the payment of 'case fees' (the fees charged by the appeals body in respect of each subscriber appeal) in the event of subscribers bringing appeals relating to infringement notifications, although ISPs will still be responsible for payment of some of the costs they incur in complying with their obligations under the Act.

Although the government and copyright owners will be relieved by the decision, this may not be the end of the matter; the appellants may seek leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The High Court grants a Norwich Pharmacal order to copyright owners

Golden Eye (International) Ltd and others v Telefonica UK Ltd [2012] EWHC 723 (Ch), 26 March 2012

A "Norwich Pharmacal" order requiring the disclosure of documents or information may be useful when infringement of intellectual property rights is suspected. In this recent case, the High Court, in granting an order against Telefonica UK limited (O2) for the disclosure of details of customers suspected of copyright infringement, has considered the manner in which Norwich Pharmacal orders may be applied to file sharing cases, the proportionality test to be applied in such circumstances and the practice of 'speculative invoicing' of alleged copyright infringers.

The case was brought by fourteen claimants, all owners of copyright in pornographic films. Ben Dover Productions, the main claimant, granted Golden Eye International Limited, the second claimant, an exclusive copyright licence with a right to bring claims for copyright infringement. The other claimants had entered into agreements with Golden Eye, all agreements being in the same form, which granted Golden Eye the right to act in relation to any breaches of copyright arising out of peer to peer copying of material across the internet.

The object of the claim was to obtain disclosure and full details of names and addresses of O2's customers who were alleged to have committed infringements of copyright through peer to peer file sharing. Evidence of infringement was obtained by the claimants use of a tracking service identifying various IP addresses which had been used to make the copyright works available to third parties. The claim raised various questions as to the operation of the Norwich Pharmacal regime, the rights of copyright owners and consumers and the practice of speculative invoicing.

O2 did not contest the claim and even agreed, in advance of the hearing, the terms of an order for disclosure of customers details through its solicitors. The court asked Consumer Focus (a statutory body representing the interests of consumers) to intervene and make representations on behalf of the intended defendants, the alleged infringers (O2's customers), since the intended defendants could not make representations themselves.

Arnold J considered in his judgment the practice of 'speculative invoicing'. The claimants intended to write to alleged infringers claiming that infringement had taken place and demanding undertakings and payment of a sum of money as compensation for the claimants' loss. If the alleged infringer chose not to settle on the terms offered by the claimants, the letter suggested that legal proceedings would be commenced and damages plus costs would be sought. In its submissions, Consumer Focus drew attention to the activities of a solicitor Andrew Crossley, trading as ACS:Law. ACS:Law had sent more than 20,000 speculative invoice letters and recovered a significant sum of money in similar circumstances claiming alleged copyright infringement. The practice of 'speculative invoicing' came under scrutiny in the Patents County Court in 2010, following which ACS:Law ceased trading in January 2011. Arnold J considered the similarities and differences between the ACS:Law practice and the claimants' intentions in the present case and concluded that the terms of the letter proposed to be sent by the claimants were objectionable in a number of respects and that the amount claimed in compensation (£700) was unsupportable; the settlement sum should be negotiated with each intended defendant once relevant information regarding infringement had been disclosed.

In considering the Norwich Pharmacal order, the court looked at the proportionality of the proposed order including, when adopting measures to protect copyright owners, the fair balance to be struck between the protection of intellectual property rights and the protection of the fundamental rights of individuals affected by such orders. The judgment details the propositions to be considered before granting an order in the present case, including:

a. the rights of the claimants (here, the owners of copyright alleged to have been infringed who require disclosure of names and addresses of intended defendants in order to pursue infringers);

b. the rights of the intended defendants who may be ordinary consumers without access to specialised legal advice, whose privacy may be invaded and whose data protection rights may be impinged;

c. the terms of the draft order which must be proportionate as between the intended defendants and the claimant and which must not give the intended defendants the wrong impression about what the court decided when it made the order and must not cause the intended defendants unnecessary anxiety or distress. In the present case the court concluded that the terms of the order may cause unnecessary distress because the terms included an implicit threat of publicity once legal proceedings had commenced. This, combined with the pornographic nature of the films and the fact that the intended defendants may not be persons engaged in filesharing of the films, may be likely to cause distress;

d. the terms of the draft letter of claim, the impact of which on an ordinary consumer should be considered (in the present case the court considered that the letter should have made clear that the fact that an order for disclosure was made did not mean that the court had considered the merits of the allegation of infringement made against the intended defendant and further, that the letter made unjustified references to other possible infringements and an unjustified threat to take steps to slow down an intended defendant's internet connection);

e. the terms of settlement offered (here the court considered the terms to be unjustified since the claimants had no idea about the scale of infringements committed by each alleged infringer and further, that specifying an amount to be paid in settlement was not acceptable until full disclosure of information had taken place following which a settlement sum could be negotiated with each intended defendant; and finally

f. whether appropriate safeguards should be put in place for the intended defendants (which may include the appointment of a supervising solicitor, the making of a group litigation order, the selection and determination of suitable test cases and the making of a condition that all cases should be brought before the Patents County Court in order to ensure that they were dealt with by a specialised tribunal).

Arnold J held that it was proportionate to grant the Norwich Pharmacal order to Golden Eye and Ben Dover Productions provided that the order and letter of claim were worded so as to protect the interests of O2's customers. However, the court declined to make any order in favour of the other claimants; such an order, taking into account the terms of agreement between the other claimants and Golden Eye, would not proportionately and fairly balance the interests of the claimants with the intended defendants' interests and if the other claimants wanted to obtain redress for wrongs suffered, they must obtain redress themselves.

OTHER MATTERS OF INTEREST - IN BRIEF

The Information Commissioner's Office finds the Department for Education in breach of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (the "Act") over information sent from a private email account.

Information Commissioner's Office decision notice: FS50422276 (DfE)

The decision makes clear that storing information in a private e-mail account does not entitle the holder to withhold disclosure of that information; it is the purpose for which the information is held rather than where the information is held that is relevant.

The Information Commissioner's Office ("ICO") issued a decision notice finding that information sent by the Secretary of State for Education from a private non-departmental e-mail account to a named individual amounted to government departmental business, not party political business. As such, the information was considered held for the purposes of the Act and was required to be disclosed upon request. The ICO concluded that the Department for Education was in breach of section 1(1)(b) of the Act by failing to disclose it.

In its decision notice, the ICO acknowledged that the situation was a novel issue and one that may not have been anticipated when the Act was passed. In addition, the ICO recognised that it is not always easy to draw a line between official information held by a public authority and party political information. However, in this particular case the ICO considered that the requested information was held for the purposes of the Act. The ICO has published useful guidance concerning official information held in private email accounts: http://www.ico.gov.uk/news/latest_news/2011/ico-clarifies-law-oninformation-held-in-private-email-accounts-15122011.aspx"

Unfair Advantage and the BEATLE mark

You-Q BV v OHIM, Case T-369/10, 29 March 2012

In a decision which illustrates that significant reputation may provide substantially extended protection, the EU General Court has upheld the opposition by Apple Corp to a proposed Community Trade Mark ("CTM") for BEATLE for wheelchairs in class 12. The opposition under Article 8(5) of the CTM Regulation No. 207/2009 was based on various earlier word and figurative marks for "Beatles", for sound records, videos and films in class 9 and toys in class 28, but notably none in class 12.

The court ruled that the "Beatles" marks had an enormous reputation for sound records, videos and films, and a lesser reputation for toys. The existence of a link between the signs for the purpose of Article 8(5) was established by the extent of the earlier mark's reputation, the similarity of the signs and the overlap between the sections of the relevant public, in that persons with reduced mobility were part of the public at large who might buy "Beatles" goods. The court upheld the OHIM appeal board's finding that the positive image of the Beatles marks could benefit the goods covered by the BEATLE mark which justified a finding of unfair advantage.

Evidence submitted was insufficient to prove genuine use of trade mark

Christina Arrieta D. Gross v OHIM, Case T-298/10, 8 March 2012

The EU General Court has given guidance as to what evidence is required from an applicant in order to show genuine use of a trade mark.

The General Court upheld an OHIM Board of Appeal decision that genuine use of a German word mark had not been established by production of copies of advertisements placed in German magazines.

Mr Toro Araneda applied for a Community trade mark (CTM) for a figurative mark which included the word "biodanza". The applicant in this case, Ms Christina Gross, proprietor of the German word mark BIODANZA, opposed the registration. Mr Araneda contested the admissibility of the opposition and submitted a request seeking proof of genuine use of the earlier word mark for the goods and services relied upon in support of the opposition. The Second Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the opposition and held that the evidence of use of the earlier mark submitted by the applicant was not sufficient to prove the genuine use of that trade mark.

The EU General Court then upheld the Board of Appeal's decision, ruling that genuine use of the earlier mark could not be proved by production of copies of advertising material mentioning the mark for the goods or services. The applicant needed to show sufficient distribution of the advertising material to the relevant public. In this case the applicant failed to submit copies of customer enrolment forms, invoices or other business documents in order to prove she had obtained business from the advertisements and the evidence of advertisements submitted was held to be insufficient.

Trade mark application for THRILLER LIVE made in bad faith?

In this decision concerning an application to register the word mark THRILLER LIVE for audio-related goods and services (an application opposed by Michael Jackson's estate), the IPO has partially upheld the opposition on the basis that the application for some (but not all) of the goods and services was made in bad faith.

The Flying Music Company Limited had applied to register the word mark THRILLER LIVE in classes 9 and 41 for various audio-related recording goods and services. Michael Jackson's estate administrators and a company to which Michael Jackson is said to have assigned any trade marks rights he held in THRILLER in 1984 both opposed the application under s.5(2)(b), s.5(3) and s.5(4) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (the "ACT") and claimed passing-off.

A hearing officer at the Intellectual Property Office partially upheld the opposition in relation to recorded music and images, and some of the services, on the basis that the application had been made in a manner that prima facie indicated bad faith under section 3(6) of the Act. The applicant must have known that third parties, including Mr Jackson or his assigns, had a commercial interest in the sale of recorded music and images entitled THRILLER. Further, the applicant's failure to file evidence denying the allegation and explaining its intentions counted against it.

Concerning other grounds of opposition, evidence that consumers perceive THRILLER in a trade mark sense rather than simply as the title of a well-known song, album and music video was absent. Therefore, there was no basis to conclude that THRILLER was a well known trade mark in the UK at the date of the opposed application. The grounds of opposition under s.5(2)(b) and s.5(3) of the ACT failed. The opposition based on passing off also failed since "THRILLER" was not distinctive of the commercial source of music albums and videos. In the absence of misrepresentation, the passing-off right claim also failed and the opposition under s.5(4) failed accordingly.

Finally, in relation to the remaining services in the application, including musical theatre services, the opposition failed since the IPO concluded there was no evidence that Michael Jackson had ever given musical theatre performances under the THRILLER name or that Michael Jackson ever expected to provide musical theatre services under the THRILLER name. In fact, the applicant had staged West End musical theatre performances under the THRILLER LIVE name prior to filing its application and this represented a legitimate reason for the applicant to register the trade mark THRILLER LIVE for these services. Taking all these factors into account, the hearing officer rejected the opponents' claim that the application to register the trade marks in respect of these services had been made in bad faith.

BEBIO and BEBA - a likelihood of confusion?

Hipp @ Co KG v OHIM, Case-T41/09, 28 March 2012

In this recent decision concerning likelihood of confusion, the EU General Court has considered what constitutes "the relevant public": here, average consumers who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect. Although the group would include careful parents as one category of consumer, the group would not consist exclusively of careful parents (the marks in question were for baby foods). The EU General Court has held that there was a likelihood of confusion between the applicant's proposed Community Trade Mark ("CTM") BEBIO, and the opponent's earlier CTM and international mark BEBA (both for baby foods in class 5 and other food products in classes 29 and 30) under Article 8(1)(b) of the CTM Regulation No. 207/2009.

In assessing the likelihood of confusion between the signs at issue, The EU General Court considered what constituted "the relevant public". The General Court found that the Board of Appeal was justified in holding that the relevant public was composed of average consumers who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect. The goods (baby foods) could not be considered to be potentially hazardous (they are not medicines, nor are they available on prescription only) and although "the relevant public" would include careful parents as a category of consumer, it would not consist exclusively of such consumers. The EU General Court rejected the applicant's argument that consumers for baby foods all exhibited a higher degree of attention.

In comparing the signs, the General Court also found that the appeal board was right to find that the signs at issue had an average degree of visual similarity, were phonetically similar and had a certain similarity for the Spanish-speaking consumer, who would associate the signs with the Spanish verb "beber" (to drink).

Finally, the General Court concluded that the evidence submitted by the applicant, which was intended to show that the component "beb" in BEBA was weakly distinctive, was insufficient. There was no reason to depart from the view that the consumer normally attaches more importance to the first part of words.

Even if the component "beb" could be considered to be descriptive and therefore, the earlier mark BEBA itself could be considered to be weakly distinctive, the degree of similarity between the goods covered by the marks at issue and the degree of similarity between the marks themselves were considered to be sufficiently high to justify the conclusion that there was a likelihood of confusion. Accordingly, the General Court found that the Board of Appeal was correct to hold that there was a likelihood of confusion between the marks.

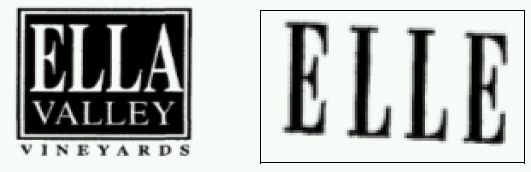

EU General Court annuls Board of Appeal's decision concerning Ella Valley Vineyards

Ella Valley Vineyards Ltd v OHIM, Case T-32/10, 9 March 2012

In a decision concerning two figurative marks, the EU General Court has considered visual (letters and fonts used) and aural (sound and rhythm) similarity of the marks before concluding that there was no likelihood that the public might establish a link between the figurative marks "Ella Valley Vineyards" and the well known "Elle".

The EU General Court has annulled a decision of the First Board of Appeal of OHIM and has found that the figurative mark "Ella Valley Vineyards" (the subject of a Community trade mark (CTM) application submitted by Ella Valley Vineyards (Adulam) Ltd, in relation to wines), was not sufficiently similar to an earlier figurative mark "Elle" (registered by Hachette Filipacchi in respect of periodicals and books for the general public in the EU) to establish a link between the marks.

The opposition to the application, based on unfair advantage of the earlier mark's reputation contrary to Article 8(5) of the CTM Regulation No. 207/2009, failed. The EU General Court held that the relevant public would "perceive the expression "ella valley" as a whole without separating the verbal elements of which it is composed and [would] therefore understand it as referring to a place name indicating the origin of the wine". Visually, the signs at issue were held to be only slightly similar (the first three letters of the marks were identical but this fact was not sufficient to offset the numerous differences existing between the signs), and although the fonts used in both signs were identical, the particular font is commonly and frequently used. Aurally, the marks also presented differences which outweighed the elements of similarity; the signs produced different sounds and rhythms which were not offset by the first three letters of the signs being identical.

The EU General Court held that, contrary to the Board of Appeal's decision, the signs at issue were not sufficiently similar for the relevant public to associate the mark applied for with the earlier mark and in the light of the differences existing between the signs there was no likelihood that the public might establish such a link.

What amounts to "communication to the public" under Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive?

Two recent ECJ decisions of importance to collecting societies have considered what amounts to "communication to the public" under Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive. One case concerned the broadcast of recordings to hotel rooms and the other case concerned the playing of background music in dental surgeries. If a broadcast is played which amounts to a "communication to the public", equitable remuneration is payable. The ECJ decisions make clear that where the nature of the broadcast is "profit-making", remuneration will be due, but the position may be different where it is not expected to have an economic impact and is not to members of the public at large.

Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive ( 2006/115/EC), requires member states to provide a right in order to ensure that "a single equitable remuneration is paid by the user, if a phonogram published for commercial purposes, or a reproduction of such phonogram, is used for broadcasting by wireless means or for any communication to the public, and to ensure that this remuneration is shared between the relevant performers and phonogram producers".

In Phonographic Performance (Ireland) Ltd v Ireland and another, Case C-162/10, 15 March 2012, the ECJ held that hotels supplying televisions or radios in guest rooms, to which a broadcast signal is distributed, were users making a communication to the public of any recordings played in the broadcast under Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive. As such, the hotels were required to pay equitable remuneration, in addition to that paid by the broadcaster. The court concluded that the guests of a hotel constituted an indeterminate number of potential listeners (so could be considered to be 'the public'), were able to listen to phonograms only as a result of the deliberate intervention of the hotel operator and that the nature of the broadcast was "profit-making" in that the supply of access to broadcasts via television or radio influenced the price a hotel could charge its guests.

The decision may be contrasted with a decision handed down on the same day in Società Consortile Fonografici (SCF) v Marco Del Corso, Case C-135/10, 15 March 2012.

In this case the ECJ held that "communication to the public" in Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive did not cover the broadcasting of recordings in private dental practices for the benefit of patients of the practice. The court concluded that there was no communication to the public since, although the patients were able to listen to the phonograms only as a result of the deliberate intervention of the dentist, the patients constituted a consistent (but not large) group of personal patients of the practice (they were not members of the public in general). In addition, patients visited the practice in succession and not all at the same time. Consequently, patients did not all hear the same phonograms and the broadcast was not likely to have an impact on the income of the practice (the practice could not expect numbers of patients to increase nor could the practice expect to increase the fees for dental treatment as a result of music playing in the background).

In the judgment, the ECJ made clear that the concepts of "communication to the public" in Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive and Article 3(1) of the Copyright Directive could not be considered to be the same because the two Articles, although similar, pursue objectives which are different (under the Copyright Directive authors have a right to authorise or prohibit communications whereas under the Rental Directive authors have a right to remuneration in the event of a communication to the public) . However, the court did set out various complementary criteria for assessing "communication to the public" under Article 8(2) of the Rental Directive based on case law concerning Article 3(1) of the Copyright Directive, namely the role played by the user or proprietor, the meaning of 'public' and the profit implications of the communications.

EPO publishes draft version of the revised Guidelines for Examination 2012

http://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/guidelines-2012.html

The European Patent Office has published online a draft version of the revised Guidelines for Examination for patent applications which will enter into force in June 2012. The Guidelines are structured in eight parts and incorporate updated content and internal instructions. To make the revised Guidelines easier to use, the EPO has included a concordance table and a table of contents with references to the old version.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.