Introduction

The stated aim of HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) is to bring about worthwhile improvements to the way Inheritance Tax (IHT) trust charges are calculated without any significant impact on the rest of the regime and in keeping with the Government's objectives of delivering fairness while maintaining tax revenues.

It is clear however that some of the measures proposed are targeted at specific tax avoidance methods. The proposals aimed at doing so will add to the compliance burden and costs for the taxpayer, adviser and HMRC alike. In the course of this submission we will suggest an alternative simpler approach, which we believe will achieve the same objective without the attendant cost.

We welcome the proposals for the alignment of filing and payment dates with the self- assessment framework, however we do not believe that these suggestions go far enough. We believe that the integration of the IHT system for trusts into self-assessment would improve compliance, reduce costs for all parties and result in a more coherent approach to the taxation of trusts.

Within professional firms, compliance and advisory work on all trust taxes, IHT, income (IT) and capital gains tax (CGT) are dealt with by the same persons. The 2006 Finance Act brought many more trusts within the IHT net. The division of responsibility between specialist trust districts (IT and CGT) and HMRC Capital Taxes is an increasingly artificial one routed in historical precedents that are no longer valid. It prevents compliance staff from seeing and understanding the whole picture and at a technical level leads to HMRC viewing individual taxes in isolation without appreciating how they interact.

The consultation raises fourteen questions. The first eight relate to proposals which are broadly described as simplification, but include anti-avoidance measures. Questions 9 and 10 relate to accumulated income and the final four to the alignment of filing and payment dates. Our responses will be grouped in the same way.

Simplification measures

The changes introduced by the Finance Act 2006 (FA2006) brought very many more trusts, particularly accumulation and maintenance trusts, into the IHT net. The consultation document recognises the increased compliance burden that this has imposed upon trustees and their advisers, many of whom lack the historical records of the settlor's cumulative transfers at the time the trust was created. This may have happened many years ago at a time when such records were not required.

For personal reasons settlors, beneficiaries and trustees of related settlements may have different professional advisers. Obtaining and sharing information may give rise to significant practical difficulties.

It is also widely recognised that the costs of compliance may far outweigh the tax charge, if any. Measures to simplify the method of calculating the charge and to reduce the compliance burden are therefore generally to be welcomed.

Proposal: It is proposed that the settlor's previous lifetime transfers should be ignored in determining the available nil-rate band for the purposes of calculating the hypothetical transfer on exit charges and ten year anniversary charges. This will avoid the problems and associated costs of having to obtain historic records and valuations.

Comment: This proposal is welcomed. Historic records are often unavailable, whilst obtaining historic valuations can be both an expensive and inaccurate process. Land and buildings may have been subject to substantial improvement and photographic or other evidence of the state of the property at the time of the transfer may not exist.

Proposal: Non-relevant property would also be ignored for the purposes of the calculation of periodic and exit charges as this relies on establishing the initial value and obtaining historical records. The advantage of these modifications would be that trustees would only be required to know information regarding exits from the trust and other trusts in the last ten years rather than potentially very old information.

Comment: For the reasons given above, we welcome these proposals.

Proposal: The nil-rate band should be split by the number of relevant property settlements which the settlor has made. This will alleviate the risk that settlors might seek to fragment ownership of property across a number of trusts to maximise the availability of reliefs or exempt amounts.

Comment: This measure is clearly aimed at fragmentation schemes involving the use of multiple settlements. Currently gifts made more than seven years before a chargeable transfer do not affect the IHT position of that transfer, including into trust. It is therefore a substantial change to share the nil-rate band with all other relevant property trusts made after the trust was set up or in existence (whenever created) when the trust came into being.

It will also add a layer of complexity and cost. Trustees will be required to obtain information that may not be readily available to them, if at all, not least because the advisers to the trustees of related settlements may be different. Misunderstandings about the number of trusts created will be common leading to inconsistent reporting. This will arise in particular where a settlor has written pension and life assurance policies in trust using the provider's standard documentation. Even if they are aware of this, since most life policies are issued in clusters rather than singly, how many trusts have been created?

Since the purpose of this proposal is to deter the use of multiple trusts, we believe that the same result can be achieved by simpler means.

Similar measures have been in place in relation to CGT for over 35 years. More recently they were introduced for IT. The CGT annual allowance and IT lower rate band of £1,000 is shared between related settlements subject to a maximum of five. Trustees should be aware if a settlor has created at least five settlements and this information is readily available to HMRC under the self-assessment system.

Example 1: If a settlor creates a large number of trusts each of which is worth at least the same amount as the current nil-rate band, the tax saved per settlement on each ten year anniversary is:

£325,000 x 6% = £19,500

If the nil rate band is set at a minimum of one fifth of the standard amount, tax payable would be:

£325,000 - (325,000/5) x 6% = £15,600

The net potential saving for the taxpayer per trust would be:

£19,500 - £15,600 = £3,900

We suspect that many of those advising on the use of fragmentation schemes concentrate on the potential tax saving, without giving adequate consideration to the costs of creating and administering each trust, including the tax compliance costs.

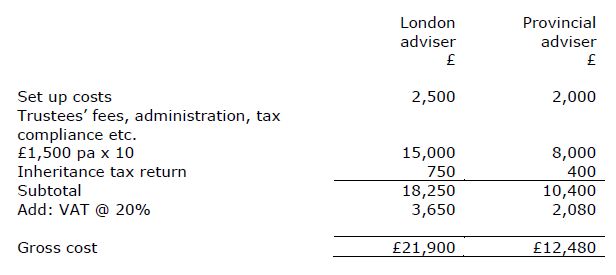

We estimate that the professional costs per trust over the first ten year period would be:

It should be apparent that, if a shared nil rate band based on the existing CGT and IT model was introduced, the costs of implementing a fragmentation scheme would dwarf any potential tax saving and should therefore act as a significant deterrent.

Because it relies on information that is already available under the self-assessment system it will be cheaper for trustees to comply with and for HMRC to check.

We also believe that greater alignment with taxes collected under the self-assessment system is a worthwhile objective in its own right.

Proposal: HMRC proposes that a simple rate of 6% of the chargeable transfer is used in the calculation of periodic and exit charges, rather than the lengthy calculations of the effective rate and settlement rate. HMRC recognise that it is not uncommon for professional costs to exceed the amount of tax at stake.

Comment: We welcome the proposal to introduce a flat rate of tax. We favour the following approach:

1. The existing method of calculation should remain the default approach;

2. Trustees should have the ability to opt in to the flat rate by a one-off election; and

3. The rate of tax should be 4% to act as an inducement.

Before addressing the questions posed, we would like to comment on example 7 on page 18 of the consultation document.

Under the proposed regime, any distributions within the 10 years before the periodic charge will reduce the available nil rate band, thus effectively charging them to the 6% tax rate on both the periodic charge and any exit charge. Under the current regime, the nil rate band is also reduced by the amount of any distributions, however currently this is only used to identify the "estate rate" and so there is no double charge to IHT. The proposed regime appears to create a double charge on transfers.

We would now like to turn to the questions raised:

Question 1: Do these proposals meet the objective of reducing complexity and administrative burdens and in what way(s)?

Response: We believe that they go some way towards meeting these objectives, however we have reservations about the proposal relating to the sharing of the nil-rate band, which we believe will add complexity and give rise to inaccurate and inconsistent reporting by trustees.

Question 2: Does a single rate of 6% present any difficulties, particularly for smaller trusts.

Response: We do not believe that the introduction of a single rate will cause difficulties. The principle is to be welcomed however the rate should be set to act as an inducement to trustees to opt in.

Question 3: How much time would the simplified method save trustees and practitioners on average per trust.

Response: No two trusts are the same and it is impossible to give a definitive and simple answer. We believe that the saving will be in hours rather than minutes.

Question 4: Will there be significant costs to trustees and practitioners familiarising themselves with the new system and if so can you quantify these.

Response: If the new system is genuinely simple, there will not be significant costs. If the system is as complex as that it replaces, yes. For this reason the nil-rate band proposals in particular, currently look flawed.

Question 5: Do HMRC's proposals in paragraphs 54-58 on the way in which the nil-rate band should be split for ten year and exit charges provide the right balance between fairness and the risk of manipulation?

Response: As noted in our responses to Questions 1 and 4 above, we believe that the current proposals are flawed. We believe that a simpler and equally effective result can be achieved by adopting models already in use for other taxes applicable to trusts.

Question 6: Are there any other ways that the nil-rate band could be split that would not risk a loss to the Exchequer.

Response: We believe that adopting the model, which has been in place for capital gains tax for many years, of dividing the nil-rate band by a maximum of five, will be significantly less costly for both trustees and HMRC. It will also act as an effective deterrent to contrived arrangements.

Question 7: Would applying the new rules from a set date cause trustees and practitioners any difficulties?

Response: Subject to the reservations expressed above in relation to the nil-rate band, we do not envisage that they would cause trustees and practitioners any undue difficulties.

Question 8: In what other way could the new rules be implemented?

Response: We suggest that there should be a one-off election to opt into the flat rate regime.

Income that may be accumulated

As has already been stated, the changes implemented by Finance Act 2006 brought many more trusts into the inheritance tax regime previously only applicable to discretionary trusts, many of which were accumulation and maintenance trusts. To consider whether there is an issue that needs to be addressed it is necessary to consider the rules on accumulation and what taxation provisions are in force in relation to that income. It would be a mistake to consider inheritance tax in isolation.

Most of the trusts with which we are familiar are subject to the law of England and Wales pertaining before the passage of the Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009. Although there are a number of different models that can be adopted for the accumulation period, most permit accumulations for a maximum:

1. Twenty one years;

2. A beneficiary reaching a specified age no later than 25, but subject to the maximum twenty one year period;

3. In the case of minors living at the end of the twenty one year period, on their attaining the age of eighteen.

In the case of most accumulation and maintenance trusts, the beneficial class will close when the first beneficiary takes an interest in possession.

The Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009 permits new trusts to accumulate income for the entire trust period. The maximum trust period has also been extended to 125 years. We have not encountered any trusts which take advantage of these provisions.

Many other jurisdictions have similar provisions to those enacted in England and Wales in 2009. Trusts written under the laws of those jurisdictions, may therefore have extended accumulation periods.

When a beneficiary takes an interest in possession a share of the undistributed income is added to his share of capital in determining the quantum of his fund. For discretionary trusts the balance of undistributed income is automatically capitalised at the end of the accumulation period. For an old style English law trust, the effect of this is that the status of a single item of income received in year one that has not been distributed needs to be considered for the purpose of the ten year charge on a maximum of two or possibly three occasions.

A trust should be a vehicle for the orderly transmission of wealth between individuals. Artificial barriers should not be put in the way of this. Most accumulation and maintenance trusts follow the pattern of the beneficiaries' lives. During the period of infancy income is either accumulated or distributed for educational or maintenance purposes. This is dictated by need and follows an irregular pattern. Between the ages of eighteen and twenty five it will provide an income whilst the beneficiary is studying at university, avoiding the need to take out student loans. It may also provide a regular level of income support whilst he is in a lower paid job. Thereafter the capital may be used in the acquisition of a home.

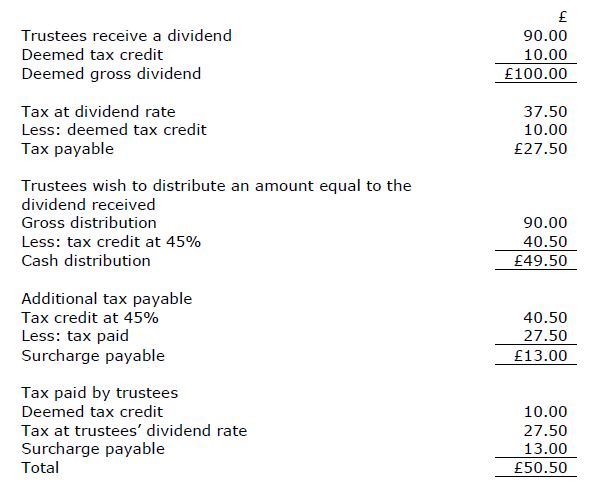

Income that is subject to the trustees' discretion is subject to IT at 37.5% in the case of dividend income and 45% for other sources. As distributions carry a tax credit at 45% and the deemed tax suffered at source on company dividends cannot be passed on, a surcharge is payable to cover both the difference in rates and the deemed dividend tax credit. This can be demonstrated as follows:

The effect of imposing IHT would be to reduce the gross amount available for distribution by £3.81 (£63.50 @6%) however because of the knock on effect on the surcharge, the additional tax raised would only be £2.10.

Because distributions are at the trustees' discretion it would be perfectly legitimate for them to avoid the charge altogether by simply resolving to distribute the income arising at the end of each tax year. The tax would then become a purely voluntary imposition. We do not believe that it is in anyone's interests to have a tax that is arbitrary in its effect or gives rise to distortions in behaviour.

It is in any case unclear as to whether income that has been subject to IHT has changed its nature. A subsequent distribution which is liable to IHT should not be liable to IT. If that was the case, whilst the trustees would no longer be liable to the distribution surcharge, the loss of tax credits would bear down more heavily on those with less income. This result would be undesirable.

The above examples are based on the earlier examples with an assumed dividend of £90 less IT at £37.50 and IHT of £3.81. The dividend surcharge would not be payable.

The proposal envisages granting a measure of relief for each quarter that each of the years in which the accumulated income had accumulated had not been treated as relevant property.

The stated aim of the consultation is to simplify the regime applicable to trusts, however this adds a further level of complexity and uncertainty. Trustees would have to maintain accurate records of when income was received and satisfy themselves as to whether or not it was relevant property. It is unclear whether distributions would be on a first in first out or last in first out basis? If there is undistributed income at the end of year 1 and a lump sum distribution is made at the end of year 2, which is equal to or less than the income of that year, from which year's income is it deemed to be made.

We will now turn to the questions raised.

Question 9: Are there any issues with using this method as a practical way of dealing with accumulations?

Response: Greater thought needs to be given to the interaction with income tax. We believe that the tax charge could in effect become a voluntary one and further that greater clarity is needed on the basis for distributions.

Question 10: Do you anticipate any additional administrative burden resulting from the proposed changes to the calculation of IHT on accumulated income? If so, what would you estimate to be the average cost per trust?

Response: The proposals have the capacity to add significantly to the administrative burden on trustees and run counter to the stated aim of simplifying the regime. We are unable to quantify the likely cost, which will vary significantly between trusts.

Aligning filing and payment dates

Inheritance Tax and its forerunner Capital Transfer Tax have always had many of the characteristics of a self-assessed tax. As noted in the introduction to this response, we are in favour of moves to align IHT with self-assessment. Where trusts are concerned, the current division of responsibilities between income tax districts and HMRC Capital Taxes looks increasingly artificial. It does not happen in the private sector.

We believe that consideration should be given to the integration of IHT on trusts into self-assessment. Supplementary pages could be included in the annual self-assessment return. Processing would be carried out by trust districts, (Nottingham) with investigations by specialist enquiry districts (Truro), who would be responsible for both self-assessment and IHT. Tax could be collected under the self-assessment payment process, with a single payment being made to cover all liabilities. The penalties and interest regime could also be aligned and automated.

This would result in both cost savings and greater efficiency, since many inquiry issues are common to a number of taxes. Valuations for example affect both CGT and IHT. HMRC staff would also obtain a better all-round understanding of trusts in general and at an individual case level.

The consultation document proposes that IHT forms should be submitted by 31 October after the end of the tax year in which the charge arose. The IHT payment would be due by the following 31 January. We believe that the filing date should be the same as for IT and CGT, 31 January rather than 31 October.

We understand that HMRC has expressed concern at the possible length of time between a chargeable event taking place and a return being submitted. This is already the case for transactions taxed under self-assessment, many of which will raise significantly higher sums of tax. A disposal liable to CGT that took place on 6 April 2013 will be included in the self-assessment tax return for the year ended 5 April 2014, which may not be submitted until 31 January 2015.

The alignment of filing dates with those of self-assessment would fit in with the compliance workload of trustees and their advisers and give rise to significant cost savings. It would also mean that returns were prepared at a time when advisers were in possession of all relevant information, including draft accounts. The quality of returns is therefore likely to be better.

Irrespective of whether IHT is aligned or integrated with self-assessment, consideration should be given to the development of software that would enable trustees who do not employ professional advisers to prepare and submit returns online, and which automatically calculates liabilities.

We believe that the benefits for all parties of incorporating IHT into the self-assessment process would outweigh any perceived disadvantages.

Question 11: Are there any issues with bringing IHT within the concept of self-assessment?

Response: We believe that this is a process that should be encouraged. The historic reasons for separate administration within HMRC look increasingly anomalous. Integration would bring about significant cost savings and improve knowledge and efficiency in collection.

Question 12: How much time will trustees save as a result of the payment and filing dates being aligned with the self-assessment framework?

Response: As noted in our answers to questions 3, 4 and 10, no two trusts are the same and it is impossible to quantify the savings that might arise as a result of aligning the filing and payment dates. We believe that whilst there will be savings for the taxpayer, there could also be significant savings for HMRC if there is not just alignment, but integration.

Question 13: What would the impact be on trustees and practitioners' clients?

Response: Alignment would enable practitioners to timetable work more efficiently. The completion of the return would become part of the compliance cycle rather than being a discrete process. It would therefore take place at a time when the practitioner was in possession of all relevant information, including accounts. As a result there is likely to be an improvement in the quality and accuracy of returns submitted.

Question 14: Will alignment bring benefits to customers in terms of reduced fees?

Response: We believe that alignment will result in lower costs, however as noted in our responses to questions 3, 4, 10 and 12, it is not possible to quantify them with any degree of accuracy.

Summary of consultation questions

Question 1: Do these proposals meet the objective of reducing complexity and administrative burdens and in what way(s)?

Response: We believe that they go some way towards meeting these objectives, however we have reservations about the proposal relating to the sharing of the nil-rate band, which we believe will add complexity and give rise to inaccurate and inconsistent reporting by trustees.

Question 2: Does a single rate of 6% present any difficulties, particularly for smaller trusts.

Response: We do not believe that the introduction of a single rate will cause difficulties. The principle is to be welcomed however the rate should be set to act as an inducement to trustees to opt in.

Question 3: How much time would the simplified method save trustees and practitioners on average per trust.

Response: No two trusts are the same and it is impossible to give a definitive and simple answer. We believe that the saving will be in hours rather than minutes.

Question 4: Will there be significant costs to trustees and practitioners familiarising themselves with the new system and if so can you quantify these.

Response: If the new system is genuinely simple, there will not be significant costs. If the system is as complex as that it replaces, yes. For this reason the nil-rate band proposals in particular, currently look flawed.

Question 5: Do HMRC's proposals in paragraphs 54-58 on the way in which the nil-rate band should be split for ten year and exit charges provide the right balance between fairness and the risk of manipulation?

Response: As noted in our responses to Questions 1 and 4 above, we believe that the current proposals are flawed. We believe that a simpler and equally effective result can be achieved by adopting models already in use for other taxes applicable to trusts.

Question 6: Are there any other ways that the nil-rate band could be split that would not risk a loss to the Exchequer.

Response: We believe that adopting the model, which has been in place for capital gains tax for many years, of dividing the nil-rate band by a maximum of five, will be significantly less costly for both trustees and HMRC. It will also act as an effective deterrent to contrived arrangements.

Question 7: Would applying the new rules from a set date cause trustees and practitioners any difficulties?

Response: Subject to the reservations expressed above in relation to the nil-rate band, we do not envisage that they would cause trustees and practitioners any undue difficulties.

Question 8: In what other way could the new rules be implemented?

Response: We suggest that there should be a one-off election to opt into the flat rate regime.

Question 9: Are there any issues with using this method as a practical way of dealing with accumulations?

Response: Greater thought needs to be given to the interaction with income tax. We believe that the tax charge could in effect become a voluntary one and further that greater clarity is needed on the basis for distributions.

Question 10: Do you anticipate any additional administrative burden resulting from the proposed changes to the calculation of IHT on accumulated income? If so, what would you estimate to be the average cost per trust?

Response: The proposals have the capacity to add significantly to the administrative burden on trustees and run counter to the stated aim of simplifying the regime. We are unable to quantify the likely cost, which will vary significantly between trusts

Question 11: Are there any issues with bringing IHT within the concept of self-assessment?

Response: We believe that this is a process that should be encouraged. The historic reasons for separate administration within HMRC look increasingly anomalous. Integration would bring about significant cost savings and improve knowledge and efficiency in collection.

Question 12: How much time will trustees save as a result of the payment and filing dates being aligned with the self-assessment framework?

Response: As noted in our answers to questions 3, 4 and 10, no two trusts are the same and it is impossible to quantify the savings that might arise as a result of aligning the filing and payment dates. We believe that whilst there will be savings for the taxpayer, there could also be significant savings for HMRC if there is not just alignment, but integration.

Question 13: What would the impact be on trustees and practitioners' clients?

Response: Alignment would enable practitioners to timetable work more efficiently. The completion of the return would become part of the compliance cycle rather than being a discrete process. It would therefore take place at a time when the practitioner was in possession of all relevant information, including accounts. As a result there is likely to be an improvement in the quality and accuracy of returns submitted.

Question 14: Will alignment bring benefits to customers in terms of reduced fees?

Response: We believe that alignment will result in lower costs, however as noted in our responses to questions 3, 4, 10 and 12, it is not possible to quantify them with any degree of accuracy.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.