In a very rare case where the CJEU had accepted an appeal in a trademark matter, it recently set aside a decision issued by the GC (Neoperl - C-93/23P) and referred it back to that court for further assessment and judgment.

1. Introduction

The CJEU ruled on two significant legal points.

Firstly, it found that, according to EU legislature, there is no order to be observed in the context of examination of the absolute grounds for refusal according to Article 7(1) of the EU Regulation No. 207/2009 ("EUTMR 2009"). It does not constitute an error of law if a sign is first examined based on Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR 2009 as to whether it has sufficient distinctive character. Specifically, it is not necessary to first assess whether a sign is capable of being represented graphically within the meaning of Article 7(1)(a) EUTMR 2009. Rather, there is no obligatory order of examination according to the pertinent EU regulations.

Secondly, the CJEU further ruled that the GC had overstepped its power by on its own accord making an assessment regarding the absolute grounds for refusal laid down in Article 7(1)(a) EUTMR 2009 on its own accord, which the Board of Appeal ("BoA") had not previously examined and in relation to which it had not yet taken a position. The amendment of the decision at issue amounted to the GC assessing for the first time facts or evidence that the BoA had not examined. In the view of CJEU, this constitutes a disregard of the binding institutional legal framework.

2. Background

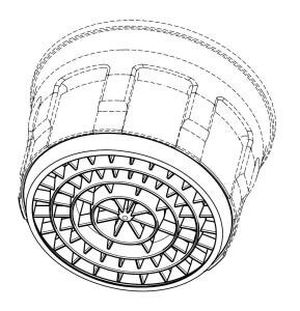

On September 1, 2016, the Swiss company Neoperl AG filed an application for the following sign:

Image source: CJEU judgement

The sign was described as "tactile position mark". Trademark protection was sought for "sanitary inserts, in particular flow regulators and flow generators".

The European Union Intellectual Property Office ("EUIPO") objected to the description "tactile position mark" and requested Neoperl to reclassify the mark as "position mark". Neoperl refused so that the application was rejected on formal grounds, namely that the application was not sufficiently precise for the purposes of Article 4 EUTMR 2009 and hence had to be refused on absolute grounds according to Article 7(1)(a) EUTMR 2009.

Subsequently, Neoperl field an appeal against the decision on October 16, 2019. The BoA dismissed the appeal on the ground that the sign was devoid of distinctive character according to Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR 2009. It explicitly did not review the appeal grounds of Neoperl that, contrary to the view of the EUIPO, the application did meet the formal requirements and was sufficiently precise, thus complying with Article 4 of the EUTMR 2009.

3. The Procedure before the GC

Neoperl appealed the decision of the BoA on August 10, 2021, arguing first an alleged infringement of Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR 2009, namely that the specific features of the sign had not been sufficiently taken into account and that the sign did have distinctive character.

Secondly, Neoperl claimed that the BOA had not met the obligation to examine the facts and undertake its own research. As a result, it had come to wrong conclusions regarding the absolute grounds.

The GC annulled the decision of the BoA. It argued that the BoA had wrongly based its rejection decision on the grounds of insufficient distinctiveness according to Article 7(1)(a) EUTMR 2009. By doing so, the BoA had not followed the legally prescribed order of examination. The GC held that it must first be examined whether a sign constitutes a trademark in the first place and is capable of being represented graphically. Only if this question is answered in the affirmative, an examination as to whether a sign has sufficient distinctive character can be undertaken.

In consequence, the GC held that the mark applied for did not meet the criteria of Article 4 EUTMR 2009 because the tactile impression of the sign could not be represented graphically even though Neoperl explicitly did not challenge the BoA's decision to examine the distinctiveness of the sign. The GC argued that it was for the GC to consider this point of its own motion and that failure to do so would be a neglect of its function as arbiter of legality if it failed to make a finding, even in the absence of any challenge by the parties on that point.

4. The appeal to the CJEU

The EUIPO appealed the decision of the GC, essentially arguing that the GC had exceeded the limits of its jurisdiction by, of its own motion and contrary to Neoperl's claims, examining by itself and then ruling on the substantive requirements of absolute grounds set out in Article 7 (1) (a) EUTMR 2009. These were expressly not examined by the BoA. It had thus unlawfully exercised the powers of the examiner on its own accord and undermined the legal protection granted to the appellant at first instance by the EU legislature.

Unsurprisingly, Neoperl chimed in with the arguments of the EUIPO: the GC exceeded the limits of its jurisdiction by ruling on the substance in the stead of the BoA. Conversely, in contrast to the EUIPO, Neoperl considered that the GC was correct in finding that the BOA had misapplied the proper order of examination.

The Advocate General ("AG") took the position that the GC had rightly found that the representation requirement had to be examined first, before all other absolute grounds for refusal. The AG did, on the other hand, find that the GC had exceeded its jurisdiction by deciding on the representation requirement. The AG argued that this required the finding of facts, which is beyond the GC's competence.

5. The Findings of the CJEU

The CJEU found that the grounds for refusal in Article 7 (1) EUTMR 2009 are independent, with each of those grounds calling for a separate examination. The GC had misinterpreted the provisions of Article 7 (1) EUTMR 2009. The fact that the legal text uses the different terms "sign" and "trademark" do not allow the conclusion that the representation requirement needs to be assessed first to confirm that it constituted a trademark within the meaning of Article 4, 7 (1) (a) EUTMR 2009. Rather, the terms "sign" and "trademark" are not used consistently in the legal text. As a result, they must be considered interchangeable. The wording of the provision does not support the GC's decision. Therefore, the BoA was entitled to deny the distinctive character of the trademark without first having to assess whether it constituted a trademark.

Regarding the second ground of appeal brought by the EUIPO, the CJEU held that the GC did not have the power to alter decisions under Article 72 (3) EUTMR 2009. This provision does not allow the GC to decide on issues on which the BoA has not yet adopted a position. The exercise of the power to alter decisions is limited to situations in which the GC, after reviewing the assessment made by the BoA, is in a position to determine, on the basis of the matters of fact and law as established, what decision the BoA was required to take. As the BoA had not examined Articles 4, 7 (1) (a) EUTMR 2009, the GC was not entitled to adopt a position on this provision.

As previously pointed out by the Advocate General, such an exercise by the GC of its power to alter decisions constitutes a disregard of the binding institutional framework as laid down in Article 72 (3) EUTMR, which seeks to ensure effective legal protection for individual parties.

The CJEU considered that the status of the proceedings does not permit a final judgement to be given, since the GC did not examine either of the two pleas put forward by Neoperl. These required a further assessment of the facts. Consequently, the case was referred back to the GC for renewed review and judgement.

6. Comments

The decision is noteworthy for two reasons:

First, the fact that the CJEU is of the opinion that all absolute grounds for refusal are on equal footing is remarkable. As the AG has rightly pointed out, there is a lot to be said for first examining whether a sign is capable of being graphically represented in the first place before reviewing its distinctiveness. If it is not clear what the subject matter of the sign to be protected is, it will likely be even more difficult to determine whether it can claim the sufficient level of distinctiveness. From a trademark practitioners' perspective, the view of the CJEU may seem odd, but in the everyday filing practice it will not make any real difference.

What is also interesting is that the CJEU has confirmed in no unclear terms that the GC has trodden on a forbidden path. Exercise of the power to alter decisions is limited strictly to situations in which the GC, after reviewing the assessment made by the BoA, is in a position to determine, on the basis of the matters of fact and of law, what decision the BoA was required to take. The GC is barred from deciding on its own accord on a subject matter upon which the BoA has not decided previously. To nevertheless do so is tantamount to reducing the scope of legal protection afforded to the individual parties, in this case the applicant Neoperl. It is encouraging to learn that the CJEU has adopted a strict formal stance as opposed to the rather casual, rights-reducing approach of the GC.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.