- in European Union

- within Privacy, Corporate/Commercial Law, Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- with readers working within the Insurance and Law Firm industries

The ICC Men's Cricket World Cup takes place this year in India and runs from 5 October to 19 November. Ten teams will compete over 48 matches in the one-day/50-over format. England are the current holders, having (almost) won on home soil back in 2019, while India, with such fervent support and more than a little local knowledge will be hopeful of becoming just the fourth host nation to lift the trophy.

With many of the ten participants harbouring legitimate hopes of victory, the game is increasingly becoming one of fine margins and invites invention across both kit and tactics. Whereas you'd struggle to get a patent on field placements, there has been a plethora of innovation when it comes to the most iconic of all cricket kit, the bat. From the veritable plank that W. G. Grace and contemporaries would've used, all the way through to today's massively profiled blades that pick up like a feather, the evolution of the cricket bat has, perhaps unsurprisingly, been underpinned by IP – and in particular, patents.

In this article, and in keeping with the theme of our recent write on patents at the Rugby World Cup, we take a light-hearted look at the history of the cricket bat, as told in the patent literature.

The iconic scoop design

With the cricket bat about to turn 400 (the first documented use of a bat was in 1624), it seems strange to start our historical tour only 50-odd years ago, but from a patent perspective, this is really where it all began.

A cricket bat's "sweet spot" is the point on the bat where you get maximum acceleration on the ball with minimal vibration. Time a shot well, and there's every chance you've hit it out of the sweet spot. Throughout the history of the game, much thought has been put into achieving larger sweet spots on bats so that the professionals can be more entertaining and the weekend hackers at least have a chance of middling a couple.

Some of the innovations behind improving the sweet spot have involved increasing the size of the bat, but as there are weight and size regulations, one can only take that idea so far. In order to reduce some of the extra weight, bat makers started removing some of the wood from the back of the bat to form "scoops". The straight-to-mind example was the iconic Gray-Nicolls "Scoop" design of the 80s, but from a patent perspective, they were actually beaten to the punch by renowned innovative batmaker John Newbery (Lance Cairns' shoulderless "Excalibur", anyone?) back in 1978.

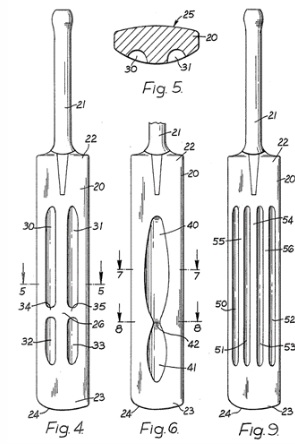

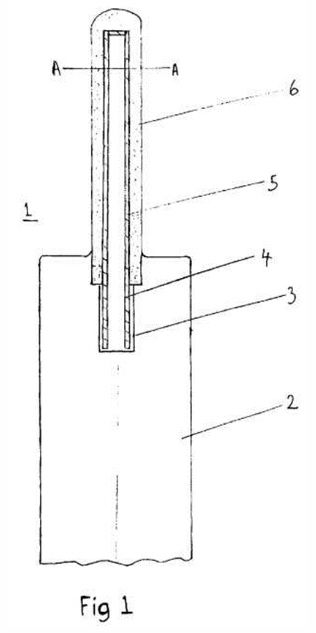

US 4,186,923 describes bats having a variety of scoops configurations, such as those shown below. In the days of heavily-pressed willow, anything that removed some of the weight and aided the balance of a bat was a bit of a godsend, and certain embodiments of these iconic bats were extremely popular as a consequence.

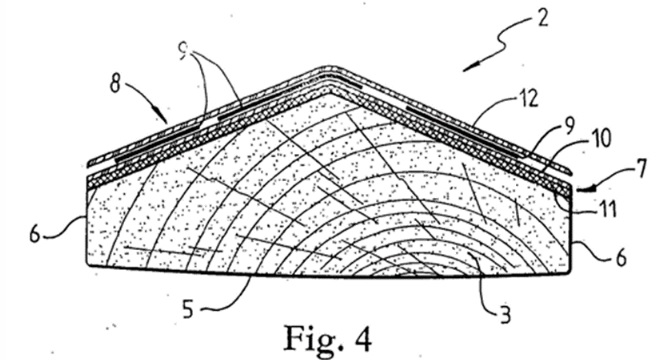

A further innovation in sweet spot technology is provided in GB 2498804, which describes a bat containing a hollow air cavity. It is made from a single piece of wood, preferably willow, and the air cavity is formed by cutting into the wood on the sides of the bat. Thanks to Isaac Newton and his coefficient of restitution, the compressed front face of the bat provides more "ping", meaning that in theory, one can hit the ball further.

It's not the only hollow bat out there; baseballers have been using hollow aluminium bats for decades, and so too did a prominent cricketer try, but you'll hear more about that soon.

I'll give the English a reason to change the ball

Without doubt, the most famous (or is that notorious) cricket bat patent out there is AU 53158/79, filed on 24 November 1978, and listing one D. K. Lillee as an inventor. Claim 1 reads: "A cricket bat containing a handle and a blade wherein the blade is formed from extruded metal". In layman's terms, it's a patent for an aluminium cricket bat, inspired by baseball bats.

Now, the commercial intent of Lillee and his business partner, Graeme Monaghan, seems to have been less interesting than some of the urban myths that have done the rounds over the years and will no doubt only continue to grow legs. As an international cricketer who had spent a lot of time on the subcontinent, all Lillee was looking to do was produce a low-cost bat that may make cricket more accessible in poorer countries. However, always prone to a spot of showmanship (not to mention the free publicity), Lillee marched out to bat in the 1979 Perth Ashes test carrying a prototype aptly branded the "ComBat" and provocatively sporting imagery of a rifle. A couple of horrible sounding connections later, England complained to the umpires that the aluminium bat was damaging the second new ball and an irate Lillee was subsequently handed a piece of willow and told to get on with it.

The following year, the MCC changed the laws of the game to require that the bat be made of wood. The ComBat had been legislated out of relevance and today sits on display at the Bradman Museum in Bowral. Having seen the prototype close up, I don't care if your surname is Lara, Tendulkar, whatever – there's no way you're timing a shot using this thing!

But back to patents. Lillee's application never granted and was marked as abandoned back in 1983. Having seen Lillee's reaction to the umpires telling him he had to change his bat, we're surprised any Examiner was brave enough to say "no". We'd have granted the patent, paid all his renewal fees and sued any infringers for him!

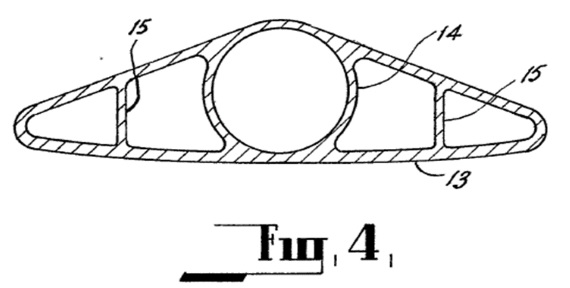

Figure 4 of the application shows a cross section of the blade of the ComBat. It's generally hollow with strengthening ribs (14) and (15). Being aluminium, it would be very light to pick up. However, that's where any commonality with a wand would've ended, we feel.

Curiously, despite the rule change, WO 2011/092714, entitled "Improvement in cricket bat" and with the preamble of claim 1 reciting "A metal cricket bat comprising..", was filed but ultimately not pursued anywhere. Mr Lillee made yet another appearance on the honours board, this time as cited prior art.

Beast mode

The early 2000s seem to have been the halcyon days of cricket bat innovation. Batmaking changed markedly around this time, with blades becoming lighter-pressed order to provide more "ping" when striking the ball. Unfortunately, a less dense striking surface is also less resilient, and so with the increase in performance came a notable decrease in longevity. Now, this is OK if you're a professional having all your gear supplied – but for the average weekend hacker, a cricket bat is an expensive piece of kit.

AU 2005100877, to A. G. Thompson Proprietary Limited (i.e., Kookaburra) is an expired, but formerly "certified" Australian "innovation patent" (i.e., a tier-2/utility model-type patent). It is entitled "Reinforced cricket bat" and is embodied in a couple of popular models around the time – Kookaburra's "Beast" and "Kahuna", for example. To the untrained eye, these bats are visually unique in that the "sticker" on the back of the bat covers the entire surface (most brands show at least a little timber on the back). However, claim 1 gives the game away: "..wherein a reinforcing layer composed of carbon fibre, glass fibre, or Kevlar or combinations of the aforesaid materials is bonded to at least part of the back surface".

Now, the specification teaches that the covering is to increase the lifespan of the bat by reinforcing it and preventing cracking. However, the MCC wasn't having any of this and did their own lab work which allegedly showed that the striking characteristics of the bat were improved. Unsurprisingly, the Beast was banned when the MCC effectively took down this, and the next patent we'll discuss, in one fell swoop.

Despite the original embodiments being banned, Kookaburra nonetheless maintained the innovation patent through to its expiry in September 2013. Subsequent legal iterations of the technology, such as the Kahuna bat used by Ricky Ponting around the time, must have remained covered by the patent, in which the key wording must have been "..at least part of the back surface".

The handle the MCC couldn't handle

Lillee's innovation had prompted the first ever change in the rules as they pertained to bats. Another patented invention prompted the second. Whereas Lillee's bat would've made it impossible to time a shot, the traditional cane handle/willow blade construction didn't – the challenge, of course, was how to make it better.

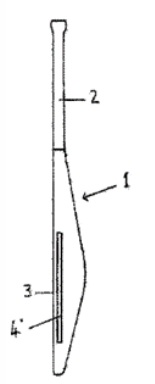

GB 2391486, to that man John Newbery again, gives less away in its title than did Mr Lillee. It's entitled "Sports bat handle", but Figure 1 gives the informed reader a bit of a clue as to what's going on. Essentially, it's a carbon fibre composite handle. The core (4) is encased in foam (6), which is then gripped in the traditional manner.

GB'486 is all about increasing the "snap" of the handle relative to that of cane (interspersed with rubber) which had been used for donkey's years. It had long been recognised that in order to optimise timing, both strength and rigidity were required in order to transfer impact to the ball. At the same time, the equipment needed to be light enough for the user to aim and swing. With the advent of carbon fibre, these two seemingly competing requirements were able to be satisfied.

GB'486 granted in July 2005, although the MCC staged an opposition of sorts. Rather than run the gauntlet of a patent opposition process, they controlled what they could and promptly changed the laws to limit performance through material constraints. Following that, the patentee stopped maintaining the patent, which was marked as "ceased" as of August 2008. The few bats produced commercially using this technology are now collectors' items.

As loose as a Mongoose

Hot on the heels of the MCC drawing its line on the sand as to which materials you could (wood) and couldn't (everything else) use, innovation in cricket bats seemed stymied.

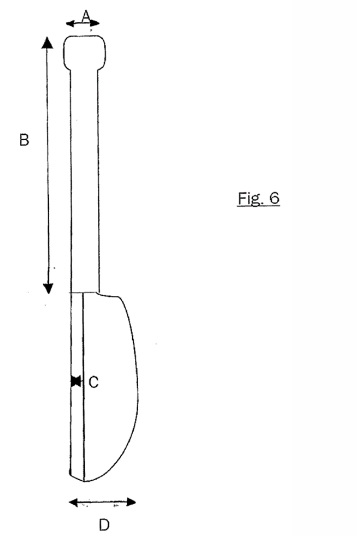

Step forward Marcus Fernandez, and AU 2009252935, to "A cricket sports bat" colloquially known as the "Mongoose". Figure 6 probably captures it best in that it's a regular sized (width, length) bat with the blade 33% shorter than a conventional bat and the handle 43% longer. The specification teaches that this leads to a larger "sweet spot" by comparison with a regular bat. The principal drawback, of course, being that a batter has less timber with which to protect his/her castle and for longer form cricket, such as test matches, the Mongoose would likely be a poor choice of kit.

However, the Mongoose represented out-of-the-box thinking, just at the time T20 cricket was taking off. No need to worry about defensive shots in this form of the game and so a bat with a larger sweet spot seemed a good option. It also helped considerably that one of the early ambassadors of the brand was a bloke called Matthew Hayden, who could hit a fairly long ball with or without the Mongoose (although probably not with the ComBat).

AU'935 was never actively prosecuted and was deemed to have lapsed as of March 2013. Whereas the Mongoose was at one time extremely popular in T20 leagues such as the IPL, its popularity declined as bowlers worked out that short-pitched fast bowling left a batter wielding a Mongoose somewhat exposed – especially on the safety front. Still, it was great fun while it lasted.

Double the handle, double the fun

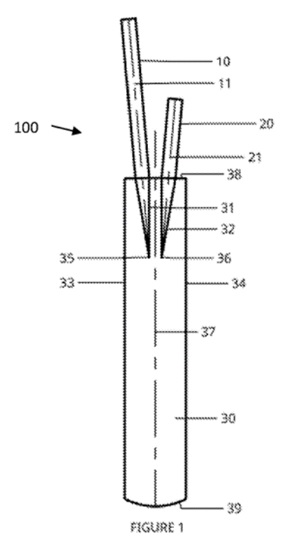

Here's an interesting idea from Ramchandra Virkar, by way of WO 2020/194039. Rather than a single handle, let's have two. To achieve this, two "V" sections are cut at the top of the blade, and angled slightly away from each other. A regular length handle is then inserted in the first V and a half-length handle in the second.

As shown in Figure 1, this results in a double-handled bat, wherein the long handle in controlled by a batter's top hand and the short handle by his/her bottom hand. The specification teaches that this arrangement enables any shock/jarring/vibration to be distributed between the two handles, which supposedly increases the prevalence of well-timed shots.

It would be interesting to trial such a bat to test not only if the above claim is true, but also to work out whether such bats were dextrous or ambidextrous – in other words, does a batter's bottom hand necessarily have to be the one furthest from their body, or can you drive the bat using the opposite configuration?

A "smart bat" almost sounds too good to be true

These days, we have "smart" everything – watches, phones, TVs, homes – so why not cricket bats? Smart bats haven't yet evolved to the point where it self-drives to ensure every shot is middled, but there have been a couple of recent developments in this regard.

Romanian patent application RO 135572, entitled "Electrical system for heating a racket/paddle/bat handle," is of course applicable to a cricket bat. The application, published in 2022, describes an electric heating system including heating wires, a power source, an activator/deactivator, a heat intensity controller, a charging device and LED indicators. The system can be used to "improve comfort for players".

Whereas RO'572 may have some utility in, say, early spring baseball in the US, or an early morning rowing session in the UK winter, its applicability to cricket is questionable. As a summer game, cricket is predominantly played in warm or at least comfortable conditions (although the UK and New Zealand "summers" can sometimes feel otherwise). Further, the most regularly changed part of a batter's kit during a long innings is their gloves, which are generally drenched in sweat and lose grip accordingly.

Perhaps then a handle cooling system could be a starter?

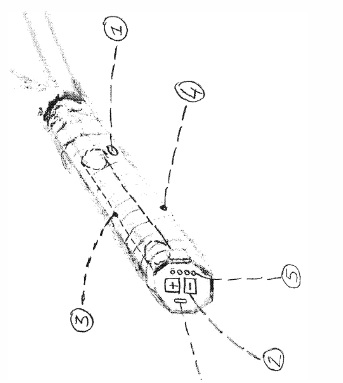

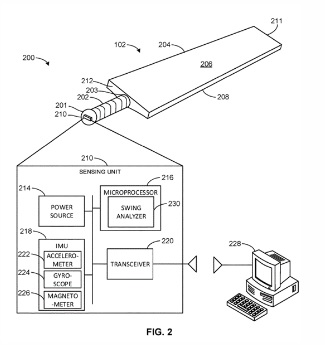

Still on the topic of smart bats, issued patent US 10,695,632 describes a cricket bat with a sensing unit coupled to it. The sensing unit includes a sensor to obtain movement data during a swing of the bat, and a swing analyser to determine whether the stroke is a straight or cross-bat shot.

The sensing unit can be used to provide accurate metrics about a batter's swing, including, for example, the follow-through pattern and/or follow-through angle for live broadcast, replay, decision making assistance, data driven coaching, new types of data mining, etc.

Having gone through only one round of prosecution, this patent was granted in 2020. When we see international batters walking out with a Bluetooth dongle sticking out the top of their handle, we'll know this one's been licensed.

Redefining the "V"

Patentable innovation within the traditional (i.e., non-smart) bat industry appears to have dropped off as a result of the MCC's refusal to budge of their prescription of what the blade and handle may comprise. Time to think within the box.

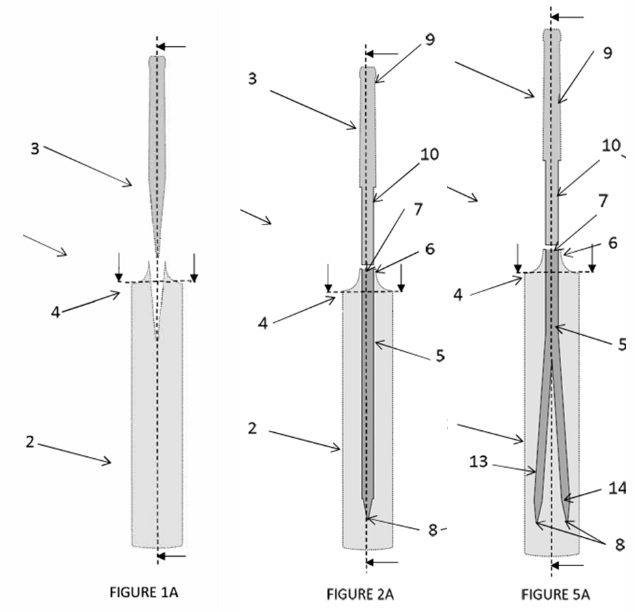

GB 2607869, to Grays of Cambridge gives little away in its title: "Cricket bat". However, rather than the traditional "V" carved out of the blade to receive the handle, the bats made according to GB'869 have an internal cavity or bore extending at least part way down the blade and a complementary cane handle is then inserted within the cavity.

The specification teaches that the shoulders of the bat, which are usually powerless and prone to cracking given their proximity to the "V", are strengthened as a result. However, arguably the greatest advantage is that a volume of willow is removed from the blade and replaced with the same volume of cane/rubber, which of course results in a weight reduction. It's almost like a contemporary take on what is now antiquated scoop technology.

Figure 1A shows the traditional "V" for handle insertion; Figure 2A shows a basic embodiment of the invention; and Figure 5A shows a slightly funky one. A good example of innovating within the rules.

We could be wrong, but we're not aware of any commercial embodiments of the technology having surfaced as yet.

What's next?

So, there we have it. A light-hearted look at the history of the cricket bat, as told in the patent literature. The most innovative period was clearly the 2000s, with some real out-of-the-box thinking on display. In looking to ensure an even contest between bat and ball, the MCC, as custodian of the game, shut a lot of this down fairly quickly. Had it not done so, who knows what weird and wonderful bat innovations we'd be witnessing today?

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]