- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

- within Insurance, Transport and Strategy topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Inhouse Counsel

This article was first published in the LexisNexis Australian Health Law Bulletin, Vol 33 Issue 4, 2025. Copyright © 2025 LexisNexis. All rights reserved.

The facts in Filmalter v Swenson1 concern an antibiotic reaction said to have been the cause or contributing factor to the development of cerebral vasculitis and hence to a stroke. However this decision of a single trial judge of the Queensland Supreme Court, following Dean v Pope2 is of particular interest for its consideration of s 22 of the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) (the Act) - the peer opinion defence provision 3.

The factual issues

The plaintiff, Mrs Sue Filmalter, sued the defendant, Dr Margaret Swenson (a general practitioner), for negligence, breach of contract and breach of ss 60 and 61 of the Australian Consumer Law (Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)). Mrs Filmalter alleged that Dr Swenson (because she had an earlier allergic reaction to a penicillin based antibiotic) inappropriately advised her and treated her with the antibiotic Norfloxacin 4 in early 2014. Norfloxacin is an antibiotic in a group of drugs called fluoroquinolones. Mrs Filmalter alleged that Dr Swenson did not properly investigate Mrs Filmalter's history of previous allergic reactions in order to identify the drug that was previously prescribed to which she reacted to, and that it was in any event inappropriate to prescribe an antibiotic in circumstances where it was alleged that Mrs Filmalter was not suffering from a urinary tract infection 5.

Mrs Filmalter alleged the Norfloxacin caused an allergic reaction which led to extreme photosensitivity which persisted for over a decade. She further alleged that her allergic reaction to Norfloxacin was a cause or contributing factor to the development of cerebral vasculitis, leading to a stroke that she suffered in 2017, causing her to be further disabled.

The defendant denied breach of duty and said that Mrs Filmalter had not suffered from an allergic reaction nor been rendered photosensitive. Dr Swenson also argued that the stroke that Mrs Filmalter suffered in 2017 was not related to the ingestion of two tablets of Norfloxacin in early 2014. The trial judge, Crow J, undertook a lengthy and careful review of the clinical history 6, before turning to the expert evidence provided by Dr Lynch for the plaintiff and Dr Dickinson by the defendant.

A significant reason for differing opinions between the experts was whether a urine test reliably showed a urinary tract infection. Determination of that issue required the trial judge to closely examine what materials were available to the defendant, and when. It transpired, based on the findings of the trial judge, that Dr Lynch's opinions were not based upon the correct assumptions. Consequently, the trial judge preferred the evidence of the defendant's expert Dr Dickinson to that of the plaintiff's expert Dr Lynch 7.

The legal issues - peer opinion defence (s 22)

The trial judge began the consideration of the legal issues by setting out the text of s 22 of the Act, which remains helpful here:

22 Standard of care for professionals

(1) A professional does not breach a duty arising from the provision of a professional service if it is established that the professional acted in a way that (at the time the service was provided) was widely accepted by peer professional opinion by a significant number of respected practitioners in the field as competent professional practice.

(2) However, peer professional opinion can not be relied on for the purposes of this section if the court considers that the opinion is irrational or contrary to a written law.

(3) The fact that there are differing peer professional opinions widely accepted by a significant number of respected practitioners in the field concerning a matter does not prevent any 1 or more (or all) of the opinions being relied on for the purposes of this section.

(4) Peer professional opinion does not have to be universally accepted to be considered widely accepted.

(5) This section does not apply to liability arising in connection with the giving of (or the failure to give) a warning, advice or other information, in relation to the risk of harm to a person, that is associated with the provision by a professional of a professional service 8.

The parties had made differing submissions as to the effect of s 22 of the Act, however the judgment is initially somewhat unclear as to what those different submissions were 9. In any event, the trial judge clearly expressed the view that s 22 "alters the standard of care" when s 22(5) is not engaged and when the elements of s 22(1) are satisfied 10.

Section 22(5) of the Act provides that s 22 will not apply to liability arising in connection with the giving of (or the failure to give) a warning, advice or other information, in relation to the risk of harm to a person. It is equivalent to s 5P of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) 11.

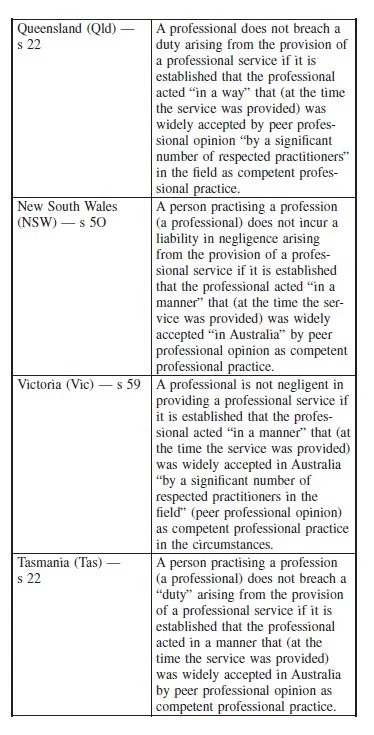

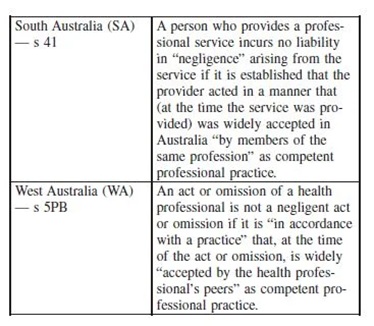

Section 22(1) sets out when a duty will not be breached, by reference to various elements. It is almost equivalent to the relevant provisions in other jurisdictions, but not quite (as seen in the table below). Key differences are underlined.

Justice Crow held that the first issue (or perhaps the first step) is to determine whether the s 22(5) exception is engaged, by reference to the pleaded breaches of duty of care 12. In this matter, the pleading was somewhat confusing as it referred to two matters at para 17(c) of the statement of claim:

(c) Advised the plaintiff that it would be inappropriate to prescribe an antibiotic until the identity of the drug that had caused the allergic reaction in South Africa was established and delayed the prescription of antibiotics until the identity of that drug had been established or the UTI had been confirmed or established 13;

The first part of the plaintiff's claim related to to the giving of advice, but the second related to the provision of treatment. The trial judge held that s 22(5) of the Act (liability arising in connection with the giving of (or the failure to give) a warning, advice or other information) was ultimately not engaged, partly as Mrs Filmalter was already acutely aware, and very scared of the prospect of having a further allergic reaction to the prescription of any antibiotic 14.

Having disposed of the potential s 22(5) exception, Crow J went on to examine the elements of s 22(1) of the Act, holding initially that it was not contentious that the defendant was a professional 15.

However the key area of interest is the meaning of the term "practice". The trial judge held:

In order to determine whether the second element of s 22(1) is satisfied so as to engage the lower standard of care as set out in s 22, the evidence does not need to identify a specific practice as such, but rather whether there is a way of professional practice which can be identified as being a widely accepted (as competent professional practice at the relevant time) manner of acting (and that seems practical), per Ward P in Dean v Pope at 233. As set out by Ward P at [235] and [236] and Brereton JA at [317] in Dean v Pope, accepting the reasoning of Basten JA and Simpson AJ in Sparkes, it was emphasised that the defendant need not bring evidence of a particular specific or established practice, but rather a consideration made by reference to how an assessment of the circumstances would be undertaken by a knowledgeable and experienced practitioner 16.

It was put to Dr Dickinson (the defendant's expert witness) in cross-examination, that his view was that peer professional opinion would support the prescription of antibiotics to which Dr Dickinson answered, "that's correct". That opinion was not challenged.17 Crow J went on to say:

. . . Dr Dickinson's evidence establishes the empirical treatment by prescription of antibiotics of a suspected medical condition or provisional diagnosis such as a UTI is a widely accepted practice by, at the very least, a significant number of respected practitioners in the field as competent professional practice. I conclude that Dr Swenson is not in breach of her duty of care to Mrs Filmalter 18.

The trial judge also held that s 22 of the Act is available to defend a claim under s 60 of the Australian Consumer Law by operation of s 275 of the Australian Consumer Law 19. However, his Honour found that there was no breach of s 60 of the Australian Consumer Law, as Dr Swenson delivered her medical services to Mrs Filtmalter with due care and skill 20. His Honour also accepted the submission that s 61 of the Australian Consumer Law had no application, as Mrs Filmalter's pleading did not attempt to particularise the services that were provided, nor any particular purpose for which those services were sought, nor how that particular purpose was made known to Dr Swenson 21. In any event, Mrs Filmalter had a probable urinary tract infection which may have progressed with fatal consequences. Prescription therefore of a class of antibiotic differing from those to which Mrs Filmalter had previously suffered from allergic reaction was a service which was reasonably fit for the purpose for which it was provided and was a service rendered with due care and skill 22.

The legal issues-what if s 22 had not been applicable

The trial judge went on to consider what should flow (contrary to the finding noted above) if s 22 of the Act was not engaged, such that it was necessary to apply the common law of negligence as modified by the Act 23. That led to the findings and conclusions as follows (with underlining added for emphasis):

I find that a diagnosis of UTI was a reasonable and highly probable provisional or working diagnosis, such that even on Mrs Filmalter's case in paragraph 17(c) the actions in not delaying the prescription was not a breach of duty of care. I prefer Dr Dickinson's opinion that Dr Swenson properly balanced the risk of the urinary tract infection progressing towards catastrophic results as being a real risk to be guarded against, as opposed to the risk of allergic reaction to a different class of antibiotic, which in all likelihood would have had a minor and likely short-term negative outcome if an allergy occurred. ...24

His Honour continued as follows:

In terms of ss 9(1)(c) and 9(2) of the Civil Liability Act 2003, in determining whether a reasonable general practitioner in the position of Dr Swenson would have taken the precaution alleged in para 17(c) of the plaintiff's claim of advising the plaintiff that it would be inappropriate to prescribe the antibiotic until any of the drugs which caused the allergic reaction in South Africa was identified,

I find that:

- The probability of harm that would occur if care was not taken was low in that the prescription of the antibiotic norfloxacin was unlikely, (on the information provided by Mrs Filmalter of her allergy was to penicillin and sulphur ingestion) to cause any significant harm.

- In terms of the seriousness of the harm, I conclude that even if Dr Swenson were incorrect, the likely outcome would be an allergic reaction. As discussed below, the reaction in South Africa was not an anaphylactic reaction.

- In terms of the burden of taking precautions to avoid the risk of harm by prescribing the norfloxacin, the burden was not high in that pressing Mrs Filmalter to obtain the name of the Entabeni Hospital and then contacting the Entabeni Hospital with the appropriate authority and obtaining the records was not an overly burdensome process. The difficulty is, as discussed above, that the records would not have been received for two weeks and in the case of urinary tract infection being probably established, the risk of the progression of the urinary tract infection to urosepsis and potentially death is too high of a risk to be taken.

- As to the social utility of the activity which creates the risk of harm, there is great social utility in the practice of medicine generally and in the prescription of antibiotics specifically when, on the balance of probability, infection is a reasonable provisional diagnosis. This is particularly so in this case the infection could properly be described as a complicated urinary tract infection, the risk in the absence of the prescription of antibiotics is the consequence of sepsis and death 25.

Ultimately his Honour concluded that, even if s 22 of the Act was not engaged, Mrs Filmalter had not proved that there was a breach of duty of care on behalf of Dr Swenson 26.

Causation

There was a great deal of complicated evidence concerning the issue of the injuries sustained by Mrs Filmalter after her ingestion of the prescribed antibiotic, norfloxacin. The trial judge accepted that Mrs Filmalter did have an allergic reaction to the norfloxacin on the evening of 9 February 2014, but found that Mrs Filmalter had no type of photosensitive reaction 27. Nor was there found to be a connection to the later stroke, with Crow J, (accepting the expert evidence of Professor Katelaris on breach of duty of care and causation), ultimately commenting that:

. . . I consider that Professor Katelaris' logic as to the likely cause of the stroke is the same as Dr Cameron's, namely that Mrs Filmalter had multiple risk factors causative of an embolic stroke and that an embolic stroke is statistically far more likely to be the cause. I accept Dr Cameron's explanation of the radiology, particularly the MRAs, as showing signs consistent with an embolic stroke. Indeed, as Professor Brew initially put it, the radiologic appearances in the MRA were unusual in terms of vasculitis. I conclude that Mrs Filmalter has suffered an embolic stroke as Mrs Filmalter has several risk factors for embolic stroke, it is by far the most likely diagnosis, combined with the radiology and as Professor Katelaris put it "common things happen commonly."28

Comments

Justice Crow followed the approach to the peer opinion defence (s 22(1) of the Act) established in Dean v Pope29 holding that the defendant need not bring evidence of a particular specific or established practice, but rather a consideration made by reference to how an assessment of the circumstances would be undertaken by a knowledgeable and experienced practitioner.

In the recent decision of Polsen v Harrison30, the NSW Court of Appeal emphasised that an assumption that the trial judge was required to conduct "an analysis of the relative merits of the competing approaches advocated by the expert witnesses" was misconceived. The judge's function was not to prefer one set of opinions to the other but to decide whether the defendant/ respondent's expert evidence satisfied the s 5O 31 criteria 32.

Justice Crow appears to have gone further than that baseline requirement, but perhaps found it necessary to do so in order to safely determine what was widely accepted by peer professional opinion by a significant number of respected practitioners in the field as competent professional practice. This is especially so, given that the practice in question in the case of Mrs Filmalter depended largely on the clinical facts - in this case, the diagnosis (or at least potential diagnosis) of a progressively serious urinary tract infection. In other words, the accepted practice can only be determined by reference to agreed or determined facts.

Footnotes

1 Filmalter v Swenson [2025] QSC 032; BC202502248.

3 Dean v Pope (2022) 110 NSWLR 398; [2022] NSWCA 260; BC202218136

3 See also: Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (CLA NSW), s 5O(1); Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) (Wrongs Act), s 59(1); Civil Liability Act 2002 (Tas) (CLA Tas), s 22(1); Civil Liability Act 1936 (SA) (CLA SA), s 41(1); Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) (CLA WA), s 5PB(1).

4 Norfloxacin is used to treat different bacterial infections of the prostate or urinary tract (bladder and kidneys). Norfloxacin is also used to treat gonorrhoea.

5 Above n 1, at [236]–[238].

6 Above n 1, at [4]–[175].

7 Above n 1, at [215].

8 Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld), s 22.

9Above n 1, at [217].

10 Above n 1, at [218].

11 See also: Wrongs Act, s 60; CLA Tas, s 22(5), CLA SA, s 41(5); CLA WA, s 5PB(2).

12 Above n 1, at [220]–[221].

13 Above n 1, at [221] para 17(c).

14 Above n 1, at [223]. The same conclusion was reached in relation to para 17(d) of the statement of claim, which said that the defendant should have requested that the plaintiff undertake further investigations by contacting the hospital to precisely identify the drug to which the plaintiff had suffered the allergic reaction.

15 Above n 1, at [226].

16 Above n 1, at [227]. The reference to Sparkes is a reference to Sparks v Hobson; Gray v Hobson [2018] NSWCA 29.

17 Above n 1, at [233].

18 Above n 1, at [234].

19 Above n 1, at [246]; Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), ss 60 and 275.

20 Above n 1, at [248].

21 Above n 1, at [249] and [253]-[255].

22 Above n 1, at [256].

23 Above n 1, at [235].

24 Above n 1, at [239].

25 Above n 1, at [240].

26 Above n 1, at [245].

27 Above n 1, at [260].

28 Above n 1, at [412].

29 Above n 2.

30 Polsen v Harrison [2024] NSWCA 224; BC202412828.

31 Ie the equivalent to s 22 of the Act.

32 Above n 30, at [59]-[60] and [62].

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.