Holding:

In Roche Diagnostics Corp. v. Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC, No. 21-1609, -1633 (Fed. Cir. April 8, 2022), the majority opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ("Federal Circuit") affirmed the district court's finding of direct infringement of U.S. Patent No. 6,808,939 ("the '939 patent"), reversed the finding of induced infringement of U.S. Patent No. 5,935,779 ("the '779 patent") and U.S. Patent No. 6,165,729 ("the '729 patent"), vacated the damages award, and remanded.

Background:

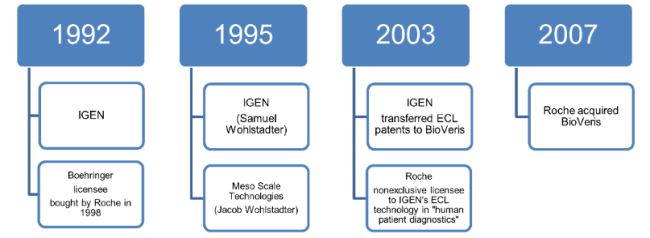

The patents at issue are owned by BioVeris, a Roche entity. According to Meso, it does not infringe those Roche patents because Meso was granted an exclusive license by a prior owner, IGEN.

Meso sued Roche in 2010 alleging that Roche breached the 2003 license with IGEN by violating the field restriction. The Delaware Court of Chancery determined that Meso was not a party to the 2003 license agreement; only BioVeris (as IGEN's successor-in-interest) could enforce the field restriction. Id. at *4.

Several years later, in 2017, Roche sued for declaratory judgment of non-infringement of Meso's rights arising from a different agreement, the 1995 license agreement. Meso counterclaimed for infringement. According to Roche, Meso's 1995 license didn't convey the rights Meso asserted. Id. at *5. At trial, the jury disagreed with Roche, finding that Meso holds an exclusive license to the asserted patent claims. The jury additionally found that Roche directly infringed claim 33 of the '939 patent, that Roche induced infringement of claim 1 of the '779 patent and claims 38 and 44 of the '729 patent, and that Roche's infringement was willful. It awarded Meso $137,250,000 in damages. Id.

In post-trial motions, the District Court of Delaware granted Roche's motion for judgment as a matter of law on willfulness and entered judgment of non-infringement on three more patents, U.S. 6,451,225 ("the '225 patent"), 6,881,536 ("the '536 patent"), and 6,881,589 ("the '589 patent"). The court agreed with Roche's argument that Meso waived compulsory infringement counterclaims as to those patents. Id.

Federal Circuit Decision:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the judgment of direct infringement of '939 patent claim 33, reversed the judgment of induced infringement of '779 patent claim 1 and '729 patent claims 38 and 44, vacated the damages award, remanded for a new trial on damages, vacated the district court's judgment of noninfringement of the '536, '589, and '225 patents, and remanded for further proceedings.

Direct Infringement

To determine the scope of Meso's rights under the 1995 license agreement, the Federal Circuit analyzed Section 2.1:

2.1. IGEN Technology. IGEN hereby grants to [Meso] an exclusive, worldwide, royalty-free license to practice the IGEN Technology to make, use and sell products or processes

(A) developed in the course of the Research Program, or

(B) utilizing or related to the Research Technologies; provided that IGEN shall not be required to grant [Meso] a license to any technology that is subject to exclusive licenses to third parties granted prior to the date hereof. In the event any such exclusive license terminates, or IGEN is otherwise no longer restricted by such license from licensing such technology to [Meso], such technology shall be, and hereby is, licensed to [Meso] pursuant thereto.

Roche argued that this provision granted Meso an exclusive license to the specific products and processes developed in the Research Program Id. at *8. Meso interpreted the provision more broadly to cover "any product or process (whenever developed) that practices the claims of IGEN's patents." Id.

The jury agreed with Meso's broader reading, particularly of the term "developed" to mean rights to patent claims as soon as Meso "developed" technology covered by them—indeed, even if Meso merely improved (i.e., further developed) preexisting technology covered by them. Id. at *8-9.

On appeal Roche relied on the provision's plain language and the parties' course of conduct. "IGEN, BioVeris, and Roche 'continued to sell' the relevant products 'through 2007 without any objection by Meso.' ... From this, Roche reasons that 'neither IGEN nor Meso understood or interpreted [prong A] to grant exclusive rights to the entirety of the patent claim.'" Id. at *9-10.

The Federal Circuit expressed some doubt as to Meso's reading of the license agreement, but ultimately did not need to resolve this dispute. With respect to the '939 patent, there was expert testimony that "'[t]he work that was done in this patent was part of the research program.' ... Roche didn't dispute this fact." Id. at *10. These rights were therefore clearly within the scope of the license under Prong A of the agreement under either party's reading of this provision. The Federal Circuit thus affirmed the district court's denial of JMOL challenging the judgment of infringement with respect to '939 patent claim 33. With respect to the '779 and '729 patent claims, the Federal Circuit determined it did not need to decide the issue of Meso's alleged rights to these patents under Prong A or B of the agreement because it was reversing the judgment of induced infringement as to these claims.

Induced Infringement

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court's judgment that Roche induced infringement of the asserted '779 and '729 patent claims due to an absence of intent and an absence of an inducing act that could support liability during the damages period set forth in 35 U.S.C. § 286. Id. at *14.

The Federal Circuit found that the district court incorrectly applied a negligence standard ("knew or should have known") rather than requiring specific intent in assessing liability for induced infringement. See Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A., 563 U.S. 754, 765-66, 131 S. Ct. 2060, 179 L. Ed. 2d 1167 (2011)). The Court further concluded that "[u]nder the proper standard, the jury's inducement conclusion is unsupportable." Id. at *16. Roche had a reasonable interpretation of the contract provisions and "a good faith belief in its reasonable interpretation of the relevant contract provisions," including the "reasonable belief that the [BioVeris] acquisition meant the elimination of field-of-use restrictions—and, hence, no possibility of patent liability." Id. at *17.

The Federal Circuit found that the jury's verdict of inducement contradicted the district court's express findings regarding Roche's subjective belief that it wasn't infringing or inducing infringement. Therefore, the Federal Circuit also vacated the damages award and remanded for a new trial on damages.

Noninfringement

The Federal Circuit vacated the district court's noninfringement judgment as to the '536, '589, and '225 patents because the district court misapplied the compulsory-counterclaim rule. Id. at *28.

The '536, '589, and '225 patents were listed in Roche's declaratory-judgment complaint, but Meso did not counterclaim for infringement of these patents.

Meso argued, inter alia, that the compulsory-counterclaim rule bars claims in future actions but does not authorize rendering judgment in the same action. Id. at *29. The Federal Circuit agreed. "This view is consistent with the advisory committee notes of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which describe the rule as being triggered by entry of judgment in an action . . . [and] the Supreme Court and this court have described the rule in ways that support that understanding. Id. at *30.

The Federal Circuit remanded for the district court to consider the appropriate disposition of any properly pled declaratory judgment claims of Roche as to these patents.

Judge Newman's Dissent

Judge Newman would have reversed on both induced infringement and direct infringement because Meso doesn't have a license to the asserted patent claims; "Roche cannot infringe patents it owns." Id. at 33.

"MSD's position is that in 1995 IGEN granted MSD the sole and exclusive right and license to all IGEN past, present, and future patents—notwithstanding the explicit limitation to technology 'developed in the course of the Research Program' or 'utilizing or related to the Research Technologies.' MSD made no such claim at the time, or when any of the patents was issued. MSD made no such claim when IGEN sold its patent estate of over 100 patents to Roche in 2007." Id. at *38. No document or any other evidence supports the MSD position. Id.

MSD's position is an "attempted revision of history." "There was not substantial evidence by which a reasonable jury could conclude that the 1995 License Agreement or any other document afforded MSD exclusive rights to the patents here at issue. The years of acquiescence in the IGEN and BioVeris and Roche practice of the patents, and MSD's failure to claim any right in any patent, negate MSD's present accusation[.]" Id. at *43-44.

Take-aways

Under 35 U.S.C. § 271, only one who makes, uses, offers to sell, sells, or imports a patented invention, without authority is an infringer. A licensee has authority from the patent owner, and therefore has a defense to an allegation of infringement.

In the U.S., initially inventorship determines ownership. But ownership rights may be subject to contracts and laws. Care must be taken with language relating to contracts licensing patent rights. Any ambiguity should be clarified as soon as possible. Moreover, careful diligence in analyzing past agreements can be critical in mergers and business acquisitions. This case highlights how a party may get a negative result based on a license clause in an agreement formed many years in the past.

A party may be liable for inducing infringement if that party induces another to directly infringe a patent. Importantly, the Supreme Court has confirmed that direct infringement is a prerequisite for a finding of inducement liability. Moreover, this case joins other post-Global Tech case law in holding that negligence is not sufficient for liability for induced infringement.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.