- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

A bouquet of cases has been dealt with by the European Court of Justice as well as the German Federal Court of Justice during the last couple of weeks concerning the protection of rather famous designs and shapes.

Not only fought Lego's mini figure successfully against the fourth (!) application for cancellation (we reported here already) , but also was the three-dimensional trademark of Piaggio's famous "Vespa" scooter secured. The European Court of Justice most probably will also have the opportunity to decide about USM's famous shelve system, soon. But one after the other:

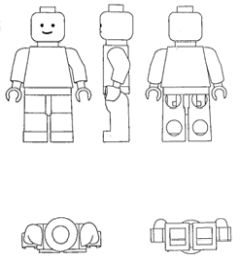

Lego's mini figures

The well-known character of Lego's mini figures could have proven to be of no use in recent proceedings concerning the three-dimensional trademark of its shape.

Source: EUTM No. 000050450

It faced the fourth attack in cancellation proceedings due to absolute bars of protection of Art. 7 (1) (e) (i) and (ii) EUTMR, that is to say, shapes exclusively resulting from the nature of the goods and shapes exclusively necessary to obtain a technical result.

Both of these absolute bars to trademark protection may not be overcome by acquired distinctiveness (Art. 7 (3) EUTMR).

That the mini figure had acquired distinctiveness among the European public was already established during the registration process of the mini figure in 2000.

Now, the Court upheld the trademarks of the mini figure with and without protrusion on its head. Both trademarks are registered (inter alia) for games and playthings of class 28.

As a side remark and as an interesting procedural aspect, the Court found the action to be inadmissible in relation to the goods in Classes 9 and 25 due to lack of reasoning, and disregarded the applicant's general references to previous submissions. In addition, the judgment of the General Court of 16 June 2015 (T-396/14) did not constitute res iudicata with respect to the present proceedings, as the applicants were not identical.

However, while the Court considered the fact that the mini figure had been subject to a Court judgment already, it still found that the Board of Appeal made errors of assessment as regards the grounds for refusal of Art. 7 (1) (e) (i) and (ii) EUTMR.

The assessment should have been based not only on the more general category "games and playthings", but also on the actual goods "interlocking building figures" as the goods had a dual nature.

Furthermore, the Board of Appeal was right to identify essential characteristics giving human traits, but erred in not identifying technical features allowing modularity as also being essential.

While the "essential characteristics" in the sense of Art. 7 (1) (e) EUTMR must be understood as referring to the most important elements of the sign, these may be identified not only from the representation of the trademark itself, but also from other information such as the public's knowledge of Lego's modular building system and documents placed on file by the applicant.

Although the Court ruled that the Board did not list quite all of the essential characteristics of the mini figure, but missed out on the protrusion on the head, the hooks on the hands, and the holes at the back of the legs and under the feet, it still found that some of these essential characteristics are imaginative and decorative (Art. 7 (1) (e) (i) EUTMR) and not exclusively necessary to obtain a technical result (Art. 7 (1) (e)(ii) EUTMR).

Especially the cylindrical shape of the head, the short, rectangular shape of the neck and the flat and angular trapezoidal shape of the torso are not inherent to the generic function of a toy figure or an interlocking building system.

Thus, not the fact that with a Lego mini figure it is possible to play as with any other toy figure without necessarily connecting it to Lego's building blocks was decisive in the case, but the mere fact that the essential characteristics of the figure also showed imagination and decorativeness, rather than pure technicity.

The three-dimensional shape of Lego's mini figure remains a valid trademark, registered on the basis of acquired distinctiveness.

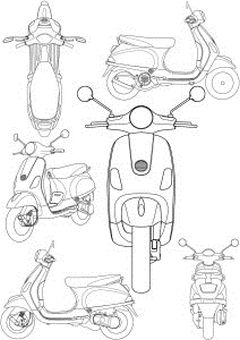

Piaggio's "Vespa" scooter

While Lego's mini figure took the threshold of registration based on acquired distinctiveness during its registration process in 2000 already, Piaggio's three-dimensional trademark of the shape of the Vespa scooter, which was also registered on the basis of acquired distinctiveness, had to overcome this threshold during cancellation proceedings initiated in 2014, again. A Chinese company, Zhongneng Industry Group Co. Ltd. had filed an application for cancellation based on lack of distinctive character, Art. 7 (1) (b) and absolute grounds of Art. 7 (1) (e) (ii) and (iii) EUTMR.

Source: EUTM No. 011686482

While the EUIPO granted the application for cancellation on the basis of lack of distinctive character and thus rejected that the three-dimensional trademark had acquired distinctiveness through use according to Art 7 (3) EUTMR, the General Court now revised that decision and found subsequently filed documents of evidence of Piaggio to be admissible and to be sufficient to prove the acquired distinctiveness.

It was found that the trademark had acquired distinctive character through use at least after its registration according to (now) Art. 59 (2) EUTMR.

Piaggio was able to show acquired distinctiveness through evidence such as opinion polls in 12 Member States of the EU. In that regard the General Court ruled that it is not necessary, that the same type of evidence filed in support of acquired distinctiveness of a trademark, which has to be shown throughout the whole of the EU, must relate to all of the Member States.

Instead, all of the documents of evidence have to be examined in a global assessment and the limitation of opinion polls to certain member states does not preclude that acquired distinctiveness may be demonstrated by additional other types of evidence.

Apart from numerous extracts from online newspapers all highlighting that the "Vespa" scooter is one of the twelve objects which marked the world design over the last hundred years according to international design experts, photographs included in the publication entitled "Il mito di Vespa" which show the use of "Vespa" scooters in world-famous films such as "Roman Holiday", and the presence of "Vespa" clubs in many Member States, the presence of the "Vespa" scooter at the Museum of Modern Art in New York were able to show the acquired distinctiveness of the shape of the "Vespa" scooter throughout the member states of the EU.

The fight for Piaggio is not over, though, as the Board of Appeal will now have to examine the trademark as to the other absolute grounds raised by Zhongneng, namely whether its essential characteristics are necessary to obtain a technical result or give it substantial value.

USM's furniture

A line of argumentation similar to that of Piaggio was also used in the case of USM trying to enforce a copyright in its rather famous USM modular furniture before the German German Federal Court of Justice (hearing on 23 November 2023, Az. I ZR 96/22) , however, most probably not as successfully.

Being a piece of applied art, the furniture has to overcome the threshold of a certain "originality" in accordance with the Cofemel principles in order to enjoy copyright protection.

USM argued in favour of a copyright in its furniture design, inter alia arguing that it is present at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

However, the judges of the German Federal Court of Justice made it clear that there are no hopes of a quick judgment in this matter. They suggested to raise four questions before the European Court of Justice before deciding in this matter. They would like to examine the details of assessment of the work of applied art further.

First of all, the judges would like to have certainty as to the relationship of copyright and design rights. In its Cofemel decision, the ECJ had stated that cumulative protection of a work under copyright and design right may be possible, however, only under the condition, that the design generates a specific, aesthetically significant visual effect. (ECJ, 12 September 2019 in the case C‑683/17 – Cofemel, para 56).

A second question could concern the "originality" of the work of applied art and the basis of its assessment. The court would like to seek advise whether the process of creation of the work is to be evaluated from the subjective point of view of the creator or whether the work itself has to be examined.

Closely linked to that is possible question number three, namely the point in time of the assessment of the "originality" of the work. In case it was possible to include circumstances after the date of creation of the work into the assessment, aspects such as the appearance of the work in museums such as MoMA could become relevant.

A possible fourth question, namely that of the relevance of the aesthetic character of the work, was discussed in the proceedings, but was not seen to be relevant from the point of view of the attorney of the defendant in this matter.

It remains to be seen whether the Court will request a preliminary ruling from the European Court of Justice in terms of all of these questions; its decision is proposed to be issued on 21 December 2023.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.